Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

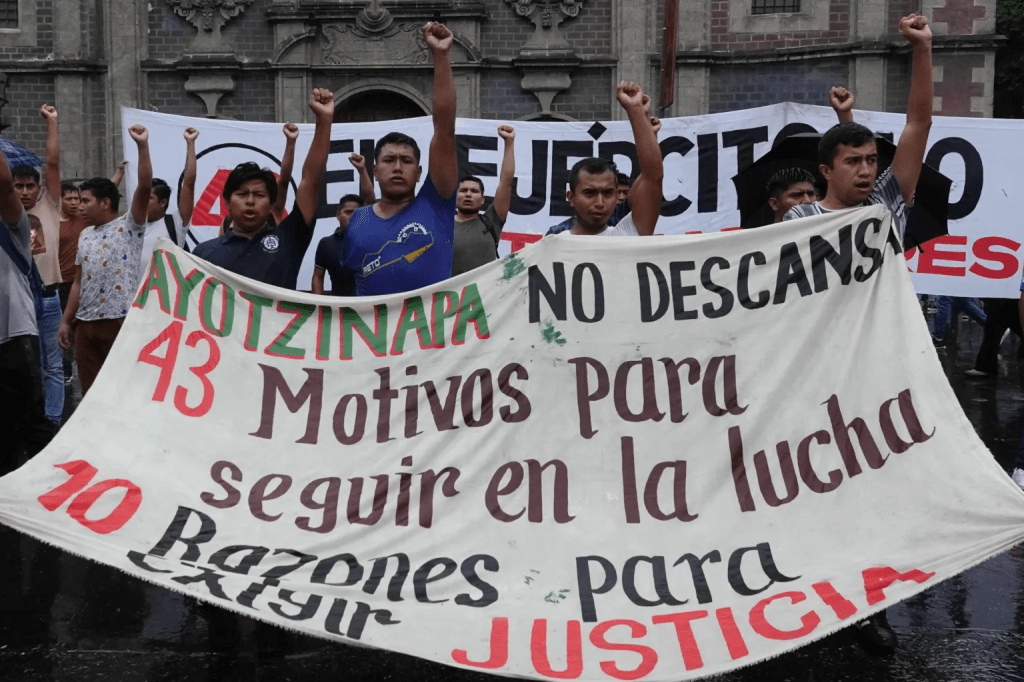

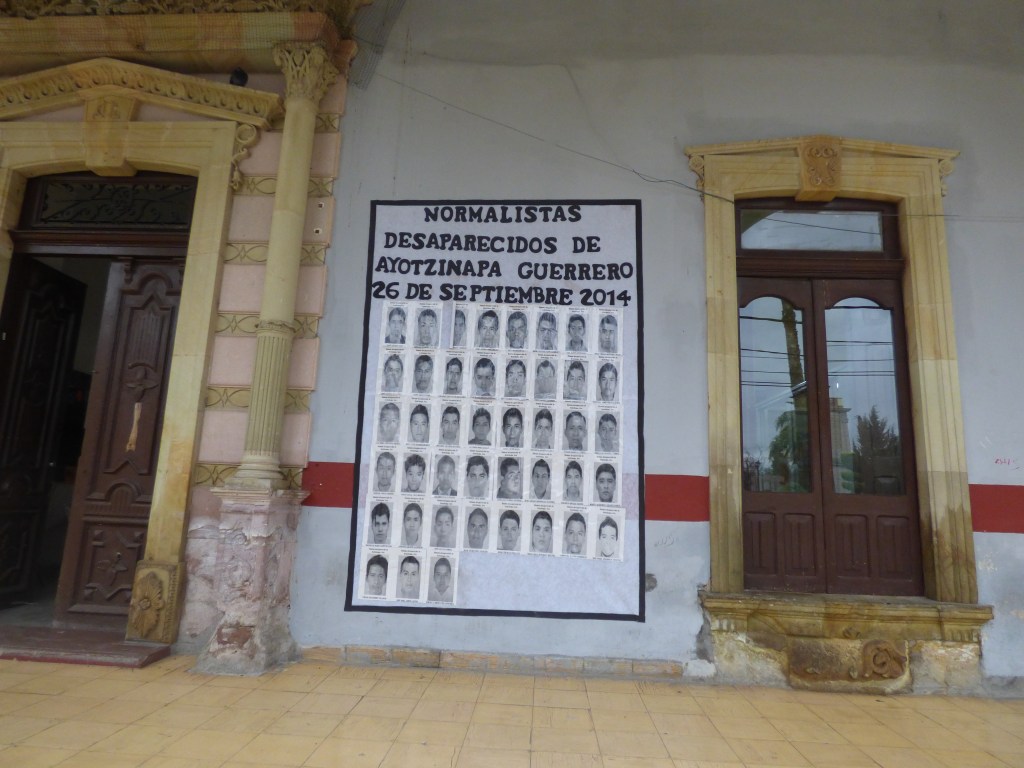

Ayotzinapa 43: Parent group searches for their disappeared in the Mexican army’s 27th Infantry Battalion barracks

By Sergio Ocampo Arista, correspondent, La Jornada

Chilpancingo, Guerrero, Mexico. The former spokesperson for the Ayotzinapa parents, Felipe de la Cruz, reported that Arturo Medina Padilla, assistant secretary for Human Rights, Population and Migration of the Ministry of the Interior Mexico, along with two parents jointly initiated “the search day” at the facilities of the 27th Infantry Battalion based in Iguala, Guerrero, for the 43 students of the Ayotzinapa college who were disappeared in September 2014.

Through a phone interview, Felipe de la Cruz explained, “today some of the parents took a turn and tomorrow another group will be searching; and I will be here next Friday in the city of Iguala at the conclusion of the search.”

It was also confirmed that during the search day (that started at 10:00 am) staff from the National Search Commission for the Ayotzinapa case participated using drones, other related machinery, and with the aid of two parents that insisted they were enough to not require others to come.

The search group used drones to survey the battalion barracks, while others used special machinery to examine other areas of the barracks looking for evidence of the Ayotzinapa 43.

It is considered that it is “part of the will and commitment of the President (Andrés Manuel López Obrador), because it was his idea and as he defends the (Mexican) Army, and we say that he did participate, and as in one way or another he has responsibilities; he has not allowed a thorough investigation in the battalion, today he said: well, so that doubts are dispelled, let’s search within the barracks, and then go ahead, if there are those responsible, if there is evidence, then things have to be done as they have to be done.”

Felipe de la Cruz assured that the search in these three days will be in the facilities of the 27th Battalion. “It is already being done outside, in the area of influence, during all these days, but now the President wanted it to be inside the battalion,” he said.

The results of this search will be announced on August 27.

____________________________

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee. Originally published by La Jornada, July 31, 2024. Click here for the original.

Shall We Start Again?

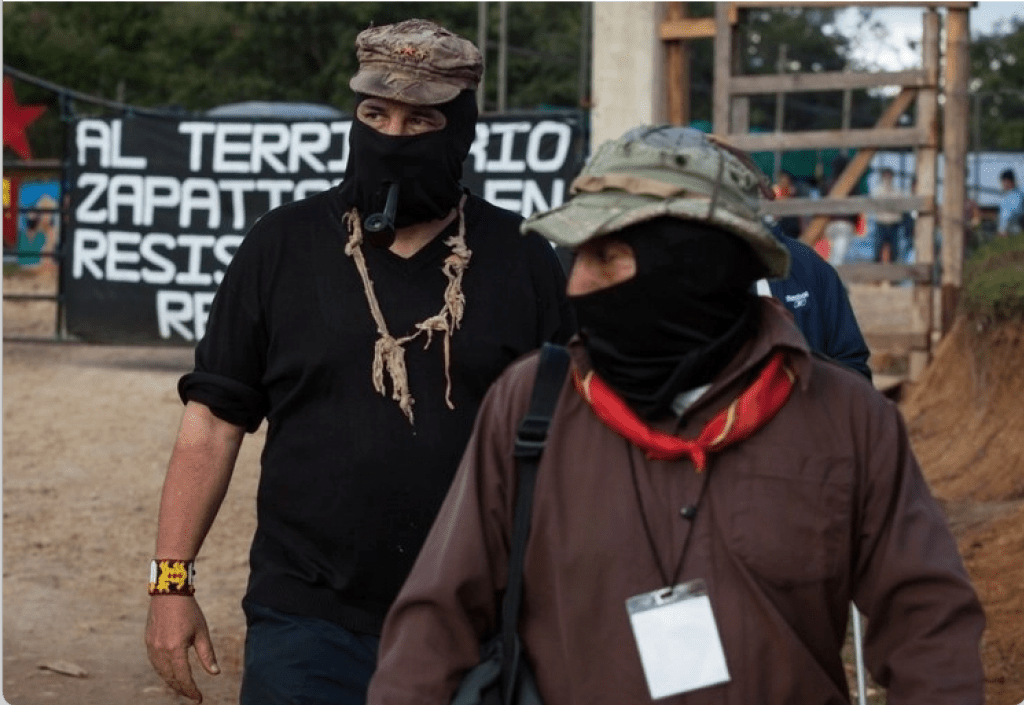

From El Capitán, EZLN, original here.

The fig tree rubs its wind

with the sandpaper of its branches,

and the forest, cunning cat,

bristles its brittle fibers.

(Romance Sonámbulo.

Federico García Lorca)

Yes, the wind and the mountain seem to have known each other for a long time. I could tell you the exact date, but it is not relevant… or something, depending. It may not be understood that firm but apparent resignation or resistance: the mountain in enduring one blow after another; the wind in its apparent retreat, giving up to return later. Always the same, always different.

But it is not these hasty twists and turns that worry the mountain. She has seen worse, if you ask her. No, what concerns them are the storms that come with bulldozers, excavators, mineral prospectors, tourist companies, factories, shopping malls, trains, governments that pretend to be what they are not, destruction, death. In short: the system.

So it would not be surprising if they reach an agreement, mountain and wind. After all, they share the same mother: Ixmucané, the most knowledgeable.

No, I won’t tell you the exact date of their first meeting. But let’s say that they have known each other for a long time, that the skeptical gesture and the sneer of contempt of the mountain at the first rays of light and gale of wind is something already routine. The same goes for the insolence of the wind when it tears off locks of the mountain’s green hair with the force of rain, wind and thunder. The scratches that the wind throws with clumsy passion, wounds like watery ditches, are not enough to attenuate the bitter rejection of the mountain. They meet, they part ways, and, in the end, they end up embracing and saying goodbye without promises or confessions. A complex relationship that has a lot to do with acceptance and rejection. “Love”, then.

-*-

They say that they say that they say that it tells a legend yet to be written, that there was a meeting and that they called the family of the Votán, guardian and heart of the people. And so the mountain said:

“My children, the most beloved, what you read before in my skin and hair is coming. The brother wind, lord Ik´, brings fierce news of another storm, the deadliest of all. We already know. And it is up to the whole family to resist and defend. You are the guardians who were created to protect. Without you, we die and wander without meaning. Without us, you become lost beings, with only emptiness in your heart and no hope in your existence. Ik´ tells what his heart saw: that, in heaven and earth, the animals share the restlessness and the anxiety.

They hear it in Cauca and in the neighborhoods of Slovenia. In Japan and in Australia. In Canada and in SLUMIL K´AJXEMK´OP. In Norway, in Sweden, in Denmark and in Nicaragua, which neither surrenders nor sells out, never! In La Polvorilla and in the wound that the trans-isthmusan train, a festering sore, makes in the hearts of the original peoples who fight. In the homelands that war multiplies like misfortunes and in those who have Open Arms to help the helpless. In Ostula and in Greenland. In tortured Haiti and in the Mayan cenotes defiled by the rails of demagogy. In the displaced and in those evicted from life by extortion. In the libertarian @ who has warned, for some time, that the State is not a solution but a problem. In the Palestinian girl who with that bomb received the unknown of life… and the certainty of death.

This is what they say to the brother Saami people, to the Mapuche, to the gypsy with the house on his back, to the original people of all lands and seas, to those who fight and resist in the land that grows upwards, to the fisherman who works life in the sea. They tell it to girls who understand the forgotten language. To boys with serious eyes. To women who seek forced absences. To people of age who put on make up on their scars like agonizing wrinkles. To those who are neither he nor she and fuck Rome. To all human beings who, like maize, have all the colors and on the table, the ground, the lap have all the ways.

But not everyone listens. Only those who look far and deep understand what that word that Ixmucané speaks, the most wise, says and warns.

So look for the way, my children. And look for the who. Raise the word with lord Ik’ in one hand and my heart in the other. Remind the world that death and tomorrow are made in the shadows of the night. Light is forged in darkness.”

-*-

Yes, the wind and the mountain met again. But this time it was different. The dawn had taken a long time to arrive, perhaps stifled by the heat, but at the first ray of light cracking the huapác, it immediately came with a rain like a slap in the face.

In the hut, the sound of the drops on the tin roof made it difficult to hear. But one could clearly see, thanks to the wobbly benevolence of a lighter, a piece of paper with multiple scratches on the table – burnt and with bits of damp tobacco – on it. The only thing that could be read clearly was:

“Patience is a virtue of the warrior.”

Okay. Cheers and may the night find us as it should be, that is, awake.

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast.

THE CAPTAIN.

August 2024.

P.S.- Yes, of course, and of the she-warrior. Yes, and of the she-he-warrior. Of the warrioroa? Really?

______________________________________________

Translated into English by the Chiapas Support Committee. Read the original at Enlace Zapatista here:

Cracks of light: Zapatismo and Palestinian resistance as inspiration for social movements

By Danae Fonseca, originally published in El Salto

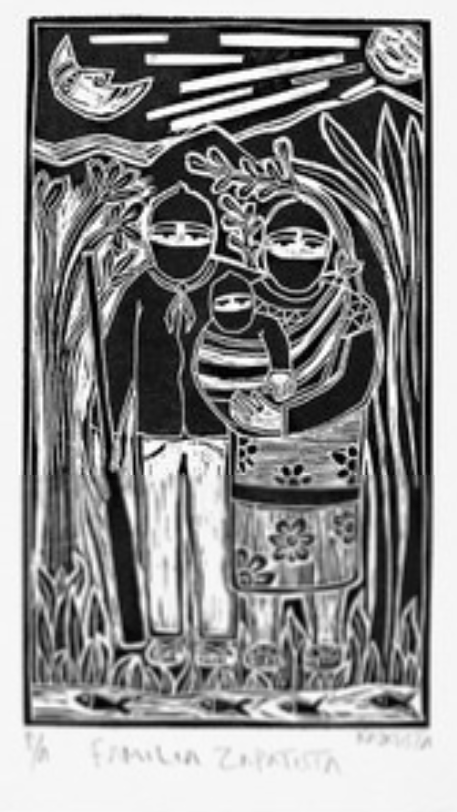

The Zapatista and Palestinian struggles share hallmarks of identity: territory, dispossession as a shared form of oppression, and the importance of memory and history to imaging other futures

I don’t know how to explain it, but it turns out that yes, words from afar may not be able to stop a bomb, but they are like a crack that opens in the black room of death which lets a little light slip through. –-Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, Mexico, January 4, 2009.

With these words, then-insurgent Subcomandante Marcos spoke about Palestine during the first festival of Dignified Rage in 2009, in the context of the fifteenth anniversary of the EZLN uprising. He prioritized this speech over the one he was going to give at the festival, reiterating the Zapatistas’ understanding that in Gaza there was a professional army killing a defenseless population.

He added: “Who fighting for justice and equality can remain silent?” This speech, titled “Of Sowings and Reapings” –taken up in a statement by Subcomandante Moisés in 2023– linked the two struggles by showing the solidarity of the Zapatistas with Palestine and their position on the murder of the Palestinian people.

In a context in which international struggle and solidarity are more necessary than ever, Chiapas and Palestine have been beacons of continued resistance for social movements internationally. Since their uprising in 1994, the Zapatistas in the mountains of the Mexican southeast have been a symbol of the fight against the capitalist system, a hope for social movements in a world increasingly devastated by savage capitalism. One of their ideas that has permeated these movements is the call to organize — each person in their geography. Palestine, meanwhile, has been an example of dignity and resistance for social organizations around the world, for resisting the occupation for 76 years, and fighting for its liberation from the Zionist state, thereby putting on the table the legitimacy of fighting against occupation by all possible means. Both movements provides reference, resistance and a space for utopias to imagine and build other worlds.

Echoes between resistances

The Zapatista and the Palestinian struggles have very significant echoes of common resistance. The first is the importance and centrality of land for both movements; the second is dispossession as a shared form of oppression and, finally, a third echo is the importance of memory and history to imagine other futures.

Land plays a central role in the Palestinian struggle. In addition to its significance as a physical space, it has a very important symbolic power. Palestinian culture is conceived of and conveyed around the land and all the activities of those who work the land: the Palestinian traditional clothes are originally that of peasants, as is the dabke, the traditional dance. The fruits of the earth are an integral part of Palestinian culture and popular vocabulary. Olive trees, with their roots running deeply into the earth, are the quintessential symbol of Palestinian resistance. Every year, March 30 is commemorated as Land Day, remembering what happened in 1976, when the Israeli army murdered seven Palestinians during the strike that denounced the systematic theft of Palestinian land. A theft that has not stopped and that increases every year through the illegal settlements of Israeli settlers in occupied Palestine.

For the Zapatistas, their very name refers to Emiliano Zapata, the Mexican revolutionary whose main demand was the distribution of the land. Thanks to his struggle, post-revolutionary Mexico saw an improvement in the conditions of agrarian distribution: the peasant movement achieved a change. However, during the rest of the century, state capitalism – and later in its neoliberal phase at the end of the 20th century – was responsible for privatizing the ejido and education, and for removing the fundamental basic rights enshrined in the Mexican constitution, which at the time stood out in comparison to other states for the social rights it granted. Article 27 of the constitution is mentioned at various times in Zapatista history. The Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle of 2005 recounts the progress that has been made thanks to the work of the Zapatista communities. Now in 2024 a new stage is inaugurated: “the common and non-property,” a new proposal from the communities for working the land.

Regarding dispossession, both the Zapatistas and the Palestinians recognize themselves as being dispossessed from the land.

The Nakba, a word that means catastrophe in Arabic, was introduced into the Arabic vocabulary by Constantin Zurayk and has already been incorporated as part of the vocabulary used around the world to refer to the expulsion of the Palestinians in 1948. However, the word Nakba is used not only to refer to the historical event of 1948, but as a constant process of dispossession by the State of Israel, which also involves the policies of apartheid, the demolition of Palestinian homes, and the constant arrest of Palestinians, among other policies that seek the oppression and extinction of the Palestinian people. Even now, in the context of the current Zionist offensive that began in October 2023, the genocide is spoken of as a second Nakba that is having more fatalities than the first in 1948. At the beginning of July 2024, The Lancet magazine estimated that the real death toll in Gaza could be 186,000 or even higher.

“The world that began to be built on October 12, 1492 is the one that made May 15, 1948 possible, and it has been a catastrophe for humanity…” Palestinians told the Zapatistas in a 2014 statement.

A group of Palestinians who attended the first Zapatista School, “Freedom according to the Zapatistas,” held in three sessions in 2013 and 2014, with the participation of about 6,000 people, issued a statement they sent to the Zapatistas in which they spoke on the relationship between the Nakba and the catastrophe suffered by the Zapatistas. In said statement, they expressed their solidarity with the Zapatista communities after the murder of teacher Galeano in 2014:

“What Galeano taught is what the Zapatista men, women, young people and elders teach every day: that the world that began to be built on October 12, 1492 is the one that made May 15, 1948 possible, and it has been a catastrophe for humanity. This is a world that requires the annihilation of those of us who refuse to live by its designs, and the only way we can win this fight, the Zapatistas teach us, is by creating a new world together. A new world as they tell us, ‘where many worlds fit.’”

The fact that people from the Palestinian youth movement were students at the first Zapatista School reveals a lot about the connection and inspiration between both struggles. In this 2014 statement addressed to the Zapatistas, the Palestinians referred to the so-called “discovery” of 1492 as a catastrophe for humanity, describing it as a moment of extermination.

Another echo of common resistance has to do with the value of memory and history in their struggle to build new futures. For Palestinians, memory is very important; The stories, images, smells and sounds are passed down through the generations about the peoples who were ethnically obliterated in 1948. Third or second generation Palestinians, who did not experience the initial expulsion directly, know the details about their native peoples. And there are a series of dates they remember and commemorate, such as the already mentioned days of the Nakba, the day of the land, the day of the Naksa or the defeat of 1967, the massacre of Sabra and Shatila, the battle of al-Karameh, the first Intifada, the second Intifada and Independence Day, are among the most important.

Palestinian poet Rafeef Ziadah wrote a very emotional poem, Chronologies, on the topic of dates and says when she introduces this poem that Palestinians “love dates.” For Palestinians, commemoration is very important, and memory becomes a weapon against the occupation and the narratives that seek to erase them from the map. It is important to show that the martyrs are remembered, that the keys to the houses, the family stories, the songs and traditional dresses, everything that constitutes and makes up Palestine, are held on to.

For their part, the Zapatistas have never stopped acknowledging their history and situating themselves in it. They have told it through their communiqués, they share it in their schools, they enact it in their plays. As they said in that first declaration of war: they define themselves as the product of 500 years of struggles: “TODAY WE SAY ENOUGH, we are the heirs of the true forgers of our nationality, the dispossessed are millions and we call on all our brothers to join this call as the only way not to die of hunger.” In the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, for example, they present a very detailed review of their history, and of the steps they took.

Evaluations and diagnostic assessments are something very Zapatista. In each of their communiqués, which is how they communicate with national and international civil society, they recount their own history, what they have been through and the path to come. Similarly, during the Journey through Life – Europe chapter*, the Zapatista delegates strongly emphasized the importance of their dead in the journey towards a future, which now appears to be at least 120 years from now.

Lighting the way

One of the unmistakable shared elements of both struggles is their image as the driving force of resistance at the international level. Based on the example and tenacity of these movements, new movements have been mobilized and created. For example, if we think of the Tahrir protests in Egypt in 2011 – one of the mobilizations that led to what is known as the Arab Spring – these were promoted by collectives that came together to support Palestine, which constituted an initial organizing force that later took on a life and demands of its own. The Zapatistas, for their part, marked the beginning of the alter-globalization movements at the end of the 20th century. Just in 1994, when the world thought that all was lost, that capitalism would end up swallowing us all, the indigenous rebels of southern Mexico emerged like a ray of light, inspiring social movements around the world.

In more recent times, the Zapatista journey through Europe meant a revitalization of the movement throughout the hundreds of territories they visited. In the midst of the global COVID pandemic, different social groups mobilized to receive the Zapatistas who had traveled thousands of kilometers. This was not minor since, just at the time of the pandemic forced us all to stay at home, thousands of people in Europe chose not to remain immobile or silent and organized to receive them. An organization was deployed from below and to the left by many groups that received the “extemporaneous’ ‘ delegation made up of 177 Zapatistas and members of the CNI that accompanied the journey to share their struggles. The most important thing was that even after the departure of the Zapatista delegation, great bonds were created that united the struggles throughout Europe. The Zapatistas sowed the seed of rebellion, which has flourished in movements and has allowed Europe itself from below and to the left – which was very isolated and separated – to unite, now also to fight against the fascisms that want to subdue us.

Today Palestine is a cause that is increasingly becoming part of the agendas of social movements. In the wake of the bloodiest stage of the Israeli genocide, that began in 2023, people have mobilized and included Palestine in their initiatives. This year, the 8M, one of the largest and most important mobilizations in Spain, has made a human chain against the genocide, it has marched with the Palestinian keffiyeh. The slogan ‘Patriarchy, Genocide, Privilege #It’s over,’ has been included as part of feminist demands. The demonstration on Critical Pride Day in Madrid had a sign with keffiyehs against Israeli pink-washing. More and more social movements are becoming aware of what Palestinian resistance means and what they are fighting against. It is also worth mentioning that one of the issues that has been put on the table during the Israeli genocide is the need to reclaim armed struggle as a form of resistance. Thanks to Samidoun, the movement that emerged to support and defend Palestinian political prisoners, assemblies are increasingly questioning how certain uses of force are legitimized and others are not, and how the discourse around legitimate defense has been hijacked.

We ourselves are the hope that exists.

“We know, as indigenous people that we are, that the people of Palestine will resist and will rise again and will walk again and will know then that, although far away on the maps, the Zapatista peoples embrace them today as we did before, as we will always do, In other words, we embrace them with our collective heart.”

With these words, Comandante Tacho of the Zapatista National Liberation Army inaugurated the first sharing between the indigenous peoples of Mexico and the Zapatista peoples in 2014. Framed in a speech welcoming the indigenous peoples of Mexico, Comandante Tacho united Zapatistas and Palestinians as peoples who suffer destruction, death and dispossession. However, the most important thing is that these movements seek a solution in an alliance in which both are protagonists. Just as Tacho said: “We ourselves are the hope that exists. . . . No one is going to come to save us, no one, absolutely no one, is going to fight for us.”

These words not only resonate as a cry of resistance, but also as a call for active solidarity. The Zapatistas and Palestinians teach us that true hope lies in the union of peoples, in the joint construction of a world where many worlds fit.

_____________________

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee. Read the original published by El Salto in Spanish here.

EZLN: 40 years after its founding and 30 years after its rebellion

By Gilberto López y Riva | La Jornada

In Mexico, a democratic transition does not take place with the collapse of the state party regime, upon the arrival of Vicente Fox to the Presidency of the Republic. There is a rotation of State parties, in which there is systemic continuity, a mere replacement of political elites, within the framework of what we have called supervised democracy.

In this context of a failed democratic transition, the rebellion of the Zapatista Mayas of January 1, 1994 erupted, on a global level, at a time when the capitalist system was celebrating its triumph over real socialism, and even when one of their spokesmen referred to the end of history. This movement represented an important oxygenation of the movements of rebellion and emancipation, of construction and strengthening of concrete utopias, which is being felt, 30 years after the historic armed uprising.

The rebellion of the indigenous peoples imposed on the national question the urgent debate on their rights to self-determination and autonomy. Which has been systematically denied by the Europeanizing and pro-American oligarchic elites, and by a mestizocracy, all rooted in deeply racist neocolonialist mentalities. It also made evident the need to accept the multilingual, multicultural and pluriethnic character of the majority of the nations of our America, including Mexico.

This rebellion opens the way to a transformation of the autonomous subjects themselves, that is, the indigenous peoples. This gave rise to the Zapatista governments of leading by obeying, revolutionary women’s laws, and the participation of young people in all instances of community power. All of this imbued with a remarkable ethical coherence that is consolidated with the application, in everyday life and political life, of Zapatista principles, which contrast with the pragmatism, deterioration and amnesia of the anti-capitalist strategies of the institutionalized left.

On the path of a failed negotiation with the Mexican State, which continues to this day, the Zapatista Mayas established an alliance, strengthened during all these decades, with the indigenous resistance movement at the national level, with the founding of the National Indigenous Congress (Congreso Nacional Indígena) in 1996. This alliance is further uplifted during Marichuy’s campaign to achieve the candidacy for the Presidency of the Republic in 2018 and, above all, in the current movement in defense of the territories against recolonization, militarization and use of organized crime as another armed actor of counterinsurgency and hitman for corporate interests.

For the anti-capitalist left, the EZLN-CNI-CIG is a reference for political action that integrates a pole of resistance not only in Mexico, but also in the international arena. This movement has allowed it to coalesce and maintain a certain unity in diversity, which cultivates the critical thinking, commitment and dedication that distinguished the revolutionary left at crucial moments in the history of the emancipation of humanity, of its fight against class exploitation, patriarchy, racism and forms of oppression of humans.

In short, the rebellion of the Zapatista Maya in 1994 and the subsequent development of this movement as a builder of autonomous powers in permanent change propose an emancipatory alternative. Although surrounded by a criminal variant of counterinsurgency, The EZLN represents a source of anti-capitalist, anti-racist and anti-patriarchal struggle, together with the National Indigenous Congress (CNI)–Indigenous Government Council (CIG, Consejo Indígena de Gobierno) and the support of numerous solidarity groups from national and international civil society. This movement raises the need to reformulate the reconstitution of the nation, but, from below, as explained in the Sixth Declaration of the Selva Lacandona, by closely linking the problems, demands, struggles and resistance of the popular majorities, that is, rooted and nourished in the space and time of the people nation.

Despite a counterinsurgency strategy, active since 1994 and currently intensified by the extreme actions of provocation by criminal paramilitarism, militarization and militarism deployed in the extent and depth of the national territory by the fourth transformation government, the EZLN celebrates 40 years of its foundation, with a bold political initiative for life, against capitalism, racism and patriarchy, which has taken its dialogue with peoples and movements in struggle to the ends of the world, starting in the rebellious land of Europe. Maintaining the flame of concrete and possible utopia, the ethical congruence of everything for everyone, nothing for us, is an extraordinary political merit of the EZLN in these 40 years of struggle and 30 years of its rebellion, without surrendering, without selling out and without give up

_______________________________________

Published by La Jornada here https://www.jornada.com.mx/2024/06/21/opinion/019a2pol

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Three years after the Journey for Life: Zapatista listening

By Raúl Zibechi

“There is no anti-capitalist movement that is capable of doing a Tour like they did, to listen without judging, to learn from other experiences,” explains Say, organized in the Zambra collective in the southern city of Málaga [Spain].

La Palmilla is a small enclave on the outskirts of Málaga, the sixth poorest neighborhood in the Spanish State, whose people survive on an average of five euros per day. The enclave is made of four-story buildings of three square meters, without terraces. Most of the community is of gypsy and Arab origin, especially Moroccans, of the third or fourth generation, although there are now many Latinos and Africans.

The members of Zambra invited the Zapatista delegation, although they never imagined that twenty young people would come to listen to half a dozen activists. They received them in an occupied orchard called “Espacio Dignidad” [Space of Dignity] that the collective cultivates in a semi-rural area. “They cut off our water, first to this garden and then to all the others,” Say complains because with the heat and sun it is almost impossible to grow crops in those conditions.

The circle is assembled at dusk when the heat subsides. Maite contrasts the difficulties of European movements in achieving a generational relieve with the advances of Zapatismo in that sense and also highlights “the cooperation between generations” that Zapatismo achieves.

“While here we really like to give our opinions, they taught us that there is a collective subject with a high capacity for listening,” Say continues.

Granja Julia [Julia’s Farm] is a collective that works four orchards on the outskirts of Paterna, in Valencia. They work with young Latinos and gypsies who, in the words of the veteran militant “Rubio”, are “the kids segregated from the educational system.” They set up a music school and a ceramics school, and the crops have a dual purpose, both productive and educational. Tomatoes, peppers, eggplants and especially sweet potatoes, a generous crop that consumes little water and is resistant to heat and pests.

Salvadoran Rolando is upset because, unlike what he knew about Zapatismo, “machinery is not shared here. Meanwhile, Joan reminds us that in the face of climate change “the old knowledge no longer serves us as much,” and Lidia reflects on Zapatismo by highlighting that “resisting without creating is one of our problems.”

Rolando intervenes again and, contrary to common sense, assures that “there is a lot of youth militancy,” and wonders if “we will be able to follow the young people.” He believes that “Zapatista listening” would be necessary to understand and give importance to what these young people are doing who, for many adults, are not true militants because they do not follow the old manuals.

Working groups are formed that in their report-backs to the plenary highlight that we are facing “times of monsters,” which makes it necessary to “create communities.” They are not deceived when they say that there is “fear of the system” and they believe that there is a lack of reflection, the ability to take risks and cultivate collective rage.

“Rubio” capped the assembly by saying that “we work with the lepers of this century,” something similar to Marx’s assertion about those who have nothing to lose, only their chains.

In Barcelona we find similar thoughts and experiences, as well as in the Valencia Alternative Fair, which this year celebrated its 35th edition. The fair contains vegetarian food, crafts, music, books, social groups and multiple conversations for three days in a public park located where the bed of the Turia River used to be.

The fair is completely self-managed: all groups must participate in the cleaning and security of the enormous space; Everything sold must be artisanal and not industrial, and each group must present receipts that they have purchased non-industrialized products to be manufactured.

Three decades is a long time: the transition from the dictatorship to the electoral regime, and from the “socialist” governments to the radicalized right.

The impression is that for European groups the Journey for Life was a mood lift, as some say, but also a mirror in which to look at themselves to learn and better understand their limitations. It’s a lot these days.

_______________________________

Originally published by Desinformémonos on June 22, 2024 here. Photographs are by Desinformémonos

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee: What have we learned from the Zapatista’s listening?

Who does Zapatismo speak to now?

EZLN / DOSSIER / December 2023

By Yásnaya Elena A. Gil

For Celso Cruz Martínez,

a flower in the desert

For Iván Gil.

Tyoskujuyëp, amuum tu’uk joojt

Every time I can, I ask: Where were you when you found out about the existence of the EZLN? What were your first impressions? I listen to the testimonies, the chronicles of people from very diverse contexts and origins involved in the demonstrations that during the first months of 1994 tried to prevent the violent and repressive responses of the Mexican government to the uprising. They tell me about the marches, the initial speculations about the type of guerrilla it was (was it more like the FARC or the M-19?), the desperate slogans that wanted to prevent the violent annihilation of a movement that was unthinkable in a atmosphere that celebrated Mexico’s supposed entry into the first world through the signing of the Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada. Some say that this uprising gave new vigor to the struggles that everyone was already fighting; others remember how their belonging to an indigenous people became particularly relevant. Others speak of their visits to the territory controlled by the Zapatistas, of their impressions as front-row witnesses of the dialogue and negotiation tables that led to the signing of the San Andrés Accords. There are those who evoke their time in the Zapatista National Liberation Front, their active participation in the March of the Color of the Earth or anecdotes related to the unprecedented fact that diverse indigenous peoples spoke at the platform of Congress. They say that the two main television stations organized, in the context of that historic march, a concert they called “United for Peace,” with Maná and the Jaguares, but later they refused to broadcast the arrival of the Zapatista contingent and their accompaniments at the main square in Mexico City. They remember the doubts expressed by Saúl Hernández himself, the Jaguares vocalist, in the press conference prior to the concert, as he foresaw that the event could become “a trap and a questioning of the visit of the Zapatistas.” Other people, more calmly, narrate their time through the Zapatista educational projects, some told me about the disappointment that the Zapatistas produced in them years later for not having supported the candidacies of Andrés Manuel López Obrador and others described their participation in the International Meetings of the Women Who Struggle organized by the Zapatistas.

I think about my own story. As a Mixe woman, as an indigenous teenager in 1994, at the beginning of Zapatismo my relationship with the movement was tangential. The first time I heard about the EZLN was from one of my teachers, Maestro Celso, who shared with us newspapers and magazines that he bought in the City of Oaxaca. I particularly remember the covers of the magazine Proceso and the front pages of La Jornada. We did not fully understand what was happening, but we read and discussed the questions that the teacher skillfully posed to us about the EZLN and our own position as Mixe adolescents of only eleven and twelve years old. In 1994 our community, Ayutla, organized a resistance movement to the influence of political parties that threatened—and threaten—communal structures. “Ayutla defends its uses and customs” was written on the walls along the main roads. The issue was in the air, in the ayuujk talks of our elders and in the frequent assemblies that boys and girls also attended. But Chiapas seemed far away. Little by little, we understood that what was happening there also appealed to us.

In the Mixe region, as in many of the indigenous peoples who are always resisting in one way or another, a movement to defend the territory had been brewing since the late seventies of the 20th century. Thinkers from the Sierra like Floriberto Díaz held intense debates and built their own categories to explain the functioning of our peoples. Together with the Zapotec anthropologist Jaime Martínez Luna, Floriberto coined the word communality and described it as a political concept. In this context, the waves of the tide that stirred the EZLN reached us, waves that silenced forever and fortunately the roar that the Salinista song [after Carlos Salinas de Gortari, president of Mexico in 1994] “Solidaridad” had left us, performed by Televisa singers and repeated over and over again on the television. Despite the mobilization in our community and the long process undertaken in the Mixe region and in many other territories, indigenous peoples were far from the major media and national debates. It seemed that we were only of interest to the indigenist lens.

Our readings and school discussions focused on texts, in Spanish, which was our second language, that tried to show solidarity with the Zapatista movement. When I migrated to the city, the relatives who welcomed me were quite involved in the issue. I remember arriving at an impressive plaza in Mexico City next to my uncle Iván, who enthusiastically explained many things to me on the day the March the Color of the Earth took the political center of the country.

Perhaps for many people on the left who are now immersed in the defense of what the President of the Republic has called the Fourth Transformation, the EZLN is no longer a valid interlocutor. Perhaps for the youth immersed in the vagaries of the partisan left, neo-Zapatismo is already a thing of the past. But one thing is undeniable: there was a time when the movement, the struggle of the indigenous peoples and the discussions about the architecture of the Mexican State in relation to the possible fulfillment of the San Andrés Accords were in the center of media spaces and constituted one of the most important topic. The spokesmen of the right scandalizedly warned of a possible “balkanization” if the right to self-determination of indigenous nations was recognized. Columnists here and there established debates from opposing positions, and the evolution of the Zapatista movement occupied the front pages. The way this country was conceived before 1994 was forever transformed. It wasn’t just about indigenous people; Zapatismo raised a mirror in which the founding myths of the Mexican State were reflected. The narrative of a single mestizo nation, the ideological aspects of the Mexican identity erected from power, the nationalism that extracted cultural and symbolic elements from the indigenous peoples while doing everything to erase them, and the very structure of the State came under scrutiny. The images reflected in that new mirror fractured the ideological certainties built with diligence, especially by the PRI governments, after the 1910 Revolution. While the EZLN resisted the violence unleashed against it and paramilitarism, society, if we can talk about it in the singular, responded questioning itself deeply. If we are not that mestizo nation where indigenous peoples are just an anthropological curiosity about to disappear, if we are not that country that is about to achieve the developmental ideals of the first world, then who are we?

Perhaps us younger people who currently fight for the rights of indigenous peoples fail to realize how our practices and discourses are deeply permeated by the uprising that began, visibly, thirty years ago. We could not talk about what we talk about without everything that Zapatismo has bequeathed to us, although we may have not participated directly in that movement that transformed the “spirit of an era.” The EZLN created a new lexicon for realities and utopias, adding elements that were not even considered in the political debate before. Being indigenous became for many something they no longer had to deny, something that pointed to a struggle of which they could be proud. Even those who did not or do not agree with the Zapatista movement have been impacted, by contrast, in their practices and discourses.

Although it was a gatopardista strategy (making things change in appearance so that the structure remains the same), the very architecture of the Mexican State was transformed. For not fully realizing the San Andrés Accords that it had signed, the government implemented a series of changes in many of its institutions. Without the Zapatista uprising, the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas) or the General Coordination of Intercultural and Bilingual Education (Coordinación General de Educación Intercultural y Bilingüe), to mention a couple of examples, would not have become a reality. While attacks were being carried out against the Zapatista communities, the administrative structures of the State opened here and there projects, departments or initiatives that now considered the existence of the indigenous peoples, with which they intended to serve them.

The powerful discursive influence of the EZLN is still valid. Even the speeches of power in the current pre-campaigns (let’s call them that once and for all) for the Presidency of the Republic have appropriated its language: Claudia Sheinbaum says, paraphrasing the words of Commander Ramona, “never again a Mexico without us;” López Obrador, for his part, often uses one of the principles of Zapatismo as a slogan, “lead by obeying,” despite the fact that his followers have disqualified the EZLN as a political force and have even accused it of being just an “invention” by Carlos Salinas de Gortari.

Despite what neo-Zapatismo has meant in the history of this country, a part of the Mexican left has broken with the EZLN. The recent mobilization to stop the war against the Zapatista people had little echo on the partisan left. The armed attacks faced by the base communities and the Caracoles shows us that the violence against the movement and its support bases continues and even worsens through incursions into their territories; but they rarely occupy the front page of the newspapers and in the morning press conferences the president, who once visited Zapatista territory, remains silent about Chiapas and the violence that engulfs it.

Different voices have explained how this estrangement came to be. Beyond the anecdotal and the accusations, I believe that there is a fundamental ideological shift that the EZLN knew how to make, but a good part of the left, now Obradorista, could not do so. After the Mexican government betrayed the San Andrés Accords that it had previously signed, the EZLN and its bases created self-management organizational structures called Caracoles, represented by the Good Government Juntas. The fact that they functioned—and function—outside the logic of the State showed how far we were from that EZLN that in the First Declaration of the Lacandona Jungle called not to stop fighting until forming “a government of our free and democratic country.” It was no longer about the seizure of power so that, from the scaffolding of the State, the rights of indigenous peoples were guaranteed and a new government was formed. The idea was to build another reality with its own self-managing mechanisms. The EZLN, which at first emphasized that its struggle was attached to the Mexican Constitution, now moved away from the desire to reform the State and opted for the creation of concrete structures to coordinate life in common based on anti-capitalist principles. This important shift also reminds me of the change of objectives in the struggle of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which, from fighting for its own State, is now committed to the creation of autonomous self-managed and confederated bodies, a horizon that transcends the nation-state model, a post-state we could say.

A good part of the Mexican left finds it difficult to understand and decode struggles that do not involve the conquest of state institutions. It was to be expected that the new horizon of the EZLN would seem incomprehensible to many. The Quiché anthropologist Gladys Tzul Tzul speaks of the “desire for the State,” and it is precisely the desire that Zapatismo got rid of. Those who continue to see the conquest of state power as the only horizon of political struggle find themselves more comfortable in Obradorismo [the politics of the López Obrador presidency].

This profound misunderstanding is reflected in several phenomena. At the beginning of López Obrador’s six-year term, both Adelfo Regino, current director of the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas) and former Zapatista advisor, and López Obrador himself promised that an indigenous reform would finally make the San Andrés Accords a reality, although the EZLN has clearly said that to its members, these reformist agreements had already been surpassed. Another evidence that the partisan left does not fully understand the current objectives of Zapatismo is the confusion and annoyance that its members expressed when the EZLN did not join in the Obradorismo, since they conceived a natural alliance from their “desire for a State.” A third piece of evidence was the insistence with which they called María de Jesús Patricio Martínez a “candidate for the Presidency of the Republic,” despite the fact that she was the spokesperson for a broad movement that did not intend to take over the power of the State, but rather to put bring into the public debate topics that none of the candidates even touched on.

Who feels challenged by the EZLN now? Apparently, it is not the Mexican politicians who appropriate their phrases, although not their principles; nor their detractors, who claim that they have not joined the López Obrador movement, nor even those people who long for compliance with the San Andrés Accords. Who is the EZLN speaking to now? To those who question the developmental model that has placed humanity in the climate emergency, the greatest catastrophe caused by capitalism. If the liberal democracies of the world and the nation-state have been functional for the capitalism that is providing us with death, the EZLN proposes urgent and radical strategies. Zapatismo no longer talks about “advancing towards the capital of the country, defeating the Mexican federal army” and then forming a new government. But it continues to propose, yes, the creation of a world in which many worlds fit, and that world is definitely not achieved by taking state power to reform it. We will have to follow the EZLN in that turn to make life possible in a future that seems to promise us death.

____________________________________

Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil is a writer, linguist, translator, researcher and Ayuujk (Mixe) activist. Aguilar’s work is focused on the study and promotion of linguistic diversity, especially with regards to the endangered original languages of Mexico, as is the case with her native tongue, Ayuujk.

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee from the original published by the Revisita de la Universidad de México available in Spanish at: https://www.revistadelauniversidad.mx/articles/f0bcac1c-38b4-4e72-88ee-a99e90bfb0d0/a-quienes-les-habla-el-zapatismo-ahora

Tierras Milperas: Mexican migrants cultivate food sovereignty in California

By Raúl Zibechi | Desinformémonos [In Watsonville, California]

The laid-back and calm rhythm of the city is palpable in every corner, in the identical houses built of wood, generating the appearance of a life without surprises or problems. Everything changes when they tell us that there are three or four families in each house, because we are in one of the most expensive corners of California. Watsonville barely has more than 50,000 inhabitants, 83 percent are Latino and 73 percent live in poverty.

They welcome us to Hugo and Carmen’s home, where Paula has prepared a succulent Mexican breakfast with homemade tortillas, which Rocío serves with her contagious smile. While we eat, they begin to explain what the Tierras Milperas collective is all about. There are several generations of migrants, the vast majority of them Mexican, with long experience in agricultural work. Many of them have a deep understanding of extractive agribusiness, as they work picking blackberries and strawberries in one of the most productive valleys on the Central Coast of California.

Paula brings tamales to the table, while several voices tell us that she teaches a Nixtamal Workshop, in which several women from the collective participate. For a decade they have been planting five community spaces that they name: Starlight, Jardín del Río, Valle Verde, Pájaro and Piece of Heaven. They are also beginning to work on a larger space, which they call Corralito, names always decided in assembly.

There are 120 families working the land, producing what they consume with enormous joy and pride. In addition to the monthly assembly in which decisions are made, they have a Community Governance Commission made up of six people who have more experience in cultivation and in the movement. The Milpero Autonomous Council is made up of older people and a young person, who propose projects to the assembly and guide the group.

Flowers or food

The time has come to get to know the community “gardens.” In the Jardín del Río we are welcomed by a man seasoned in the land with long experience as a farmer, named José. He explains that the main problem in the region is housing, with abusive prices because Watsonville is located in Silicon Valley, one of the richest areas populated by computer scientists, so “in this area housing is the most expensive in the United States.”

Behind the fence that sets off the community space, several people can be seen dragging shopping carts with clothes. Someone explains that there are more than 200 unhoused people crowded on the banks of the river, far from the indifference of the city. Walking between the eight-by-six-foot boxes, Hugo Nava, coordinator of the collective, explains that they had a conflict with the All Saints/Christ the King Episcopal Church, which terminated the lease contract and expelled them from the land. “They want us to grow flowers, not food, not to talk between families and not to hold assemblies.” Impossible to understand each other. An obvious clash of cultures.

They finally left the land after harvesting the fruits, but they found new spaces.

José tries to explain the reasons why the vast majority of the Tierras Milperas collective are women. He does it with his very Mexican style: “Women are lighter….” Silence in the round. “Because we men are more eggheads. We come home and sit down with the television control in hand, and that’s it.” Smiles of approval.

We tour the space, orderly and clean, with crops in each drawer and a meeting space presided over by a stove with its respective comal on which they prepare community meals. Rocío explains that the planter boxes are cultivated by families, but in other spaces the plants is grown directly in the soil. “As each family comes from different states with their own crops, they have formed a bank of diverse seeds that they exchange.”

On Wednesdays they hold a workshop for children who learn herbalism and Mexican foods. Carmen explains that the garden was built by the entire community that lives in the neighboring apartments. “Some of the planter boxes are cultivated in common with young people and the other part are from families. With the harvest we make community meals and celebrate the day of the dead.”

They grow milpa and other varieties such as quelite, medicinal plants, fruit trees, and they are also working with native seeds from the native peoples of California. The spaces belong to the municipality or to private individuals who give them up because they are abandoned, but the families are improving the land with the compost they work collectively.

Walking in autonomy

Before going to the assembly, we passed by one of the most consolidated spaces, called Starlight, where 45 families with agricultural experience work. “98% of the agricultural land in the United States belongs to white men,” explains Hugo, noting the persistence of structural racism that prevents migrants’ access to land.

Hugo outlines a brief history of the movement that became independent from two large NGOs in 2018, because they told them how they should do things, although they never worked the land. “There was a person in charge who didn’t even speak Spanish and he wanted to give us orders and pressured us to grow flowers. From that moment on, we started the assemblies, the movement changed direction and began to focus on food production.”

The Tierras Milperas collective is almost an exception in the world of migration, where the individualism of social advancement is hegemonic. It is differentiated by its community vocation, by using native seeds and traditional agricultural practices, but also by the exchange of knowledge between families and ecological methods. They have also created spaces for the exchange of intergenerational knowledge with young people, through the Cultivando Justicia group.

One of the characteristics of the movement is solidarity with “global farmer and indigenous struggles for territorial and food sovereignty,” as its website states. In particular, with the Coca community of Mezcala (Jalisco), in agroecology for the indigenous and peasant university that they are building. The presence of Rocío, who had to leave Mexico two years ago due to threats from the “businessman” who had illegally occupied her land, contributes to strengthening ties.

After a brief tour outside the city, we arrived at the assembly, in which almost a hundred people participated. Everyone introduces themselves in the enormous circle they have formed. Some have been farming for decades, while others recognize that they are learning. Tomato, chile, beans, garlic and maize are the crops most mentioned in the assembly.

Some older people explain that the issue is not just the consumption of healthy foods. Don Lalo assures that “cultivating is a medicine, it helps our mind.” Beside him, Cristino emphasizes identity: “The garden makes me remember where I come from and makes me return home relaxed.”

At the end of the extensive assembly, as the afternoon falls, the families share the foods they brought to this distant corner, since the authorities and land owners do not view these massive gatherings favorably, which they find suspicious. Coincidences of life, the assembly in which we participated takes place on the property of a Syrian-Palestinian family.

_____________________________________________________________

Raúl Zibechi is an Uruguayan writer, popular educator, and journalist. He writes for La Jornada, Desinformémonos, and NACLA Report on the Americas, among other outlets. Zibechi has published numerous books, including Dispersing Power, Territories in Resistance, and The New Brazil. His new book was recently translated into English by George Ygarza Quispe, Penn-Mellon Just Futures Disposessions in the Americas postdoctoral fellow.

Editor’s Note: Tierras Milperas means Land of the Milpas. In Mexico a milpa is a small plot of land or field where farmers plant and cultivate maize and other seeds. Milpa is a Nahuatl word and concept.

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee from Desinformémonos in the original here: https://desinformemonos.org/tierras-milperas-migrantes-mexicanos-en-california/

It’s not War, It’s Genocide!

By Rocio Moreno* | Desinformémonos

The inhabitants of Abya Yala know what genocide is. 500 years ago, with the European invasion in our territories, we not only suffered displacement from our lands, languages and ways of thinking, but also violence and death. According to the demographic historians Borah and Cook, 90% of the native population of what we now call Mexico, died of different causes as a result of colonization. Historians say that the population was reduced but we should begin to name correctly the deaths provoked in the name of war and invasion. What happened 500 years ago was genocide. Since ancient times wars of colonization and imposition have been justified as order and progress, and now 500 years later things have not changed much.

Today, the powerful, the conquerors-invaders continue to advance with the same strategies. What our eyes are perceiving over the past few weeks with the Palestinian people is the same colonizer. When I was a child my mother told me about the fall of Tenochtitlán. I remember that she told me that there were rivers of blood throughout the old city. The scene that I reconstructed in my mind was a place without life; of death, blood, and total destruction of the city. Now we are told that liberty and democracy are virtues given by capitalism and nation states. They also say that our civilization has left savagery behind, that now we are diplomatic. But in reality, there is a profound and subtle violence that justifies the most irrational and schizophrenic acts that we have faced. It is natural for inhabitants of Abya Yala to understand the resistance of the Palestinian people; Palestine is a mirror of our past-present. And from that past, the wounds provoked by that genocide are still here. We know their pain, and many of us feel it too.

Free Palestine!

Understanding the resistance of the Palestinian people for those of us who live in Abya Yala must be almost natural, since it is a mirror of our past-present, and from that past, there are still the deep wounds caused by a genocidal war. We know your pain, and many of us feel it too.

To rise again after a war, a profound wave of violence, with thousands and MILLIONS OF DEAD is nothing easy. In the present context of Mexico, where violence governs our entire country, I often ask myself why haven’t we been able to stop the crisis of civilization that we live every day. Each time I convince myself that surely we are rising up from the genocide of 500 years ago. Since the European invasion we have not been able to leave behind war, crisis, etc.

It pains me that the genocide we are witnessing in Palestine is like what we lived 500 years ago that we still cannot rise above it. We need to look at Palestine from a historical perspective, what is ahead for the Palestinian people, prolonged pain.

They don’t listen to us, they don’t care about us

Not even in public discourse is the war or rather the genocide that we are all witnessing acceptable. However, they still continue to manipulate us and say that this war, which is not a war, but rather a genocide, is justified. They keep telling us that there are overriding reasons to control the rebels. Increasingly, their response is cruder, more cruel and shameless.

Despite this discouraging scenario, hope emerges in different geographies across the planet. The demonstrations, marches, shouts, information forums, etc., have been a sign not only of the solidarity that exists for the Palestinian people, but also a sign that, although there are thousands, millions, of people who speak out against this genocidal war, the powerful do not care about us and are far from listening to us.

Not only across the planet, but among the Israeli people and the United States themselves, there is a rejection of the massacre being carried out on the Palestinian people and they also demand a cease fire. In those moments, the powerful once again show us that they don’t care about us at all. Our lives mean absolutely nothing. How long will we understand that they don’t care about us?

Palestine Unmasks the System of Death

Palestine unmasks the capitalist patriarchal system, and makes visible its horrible intentions against humanity and the entire planet. Ethics, respect, compassion, brotherhood, and life itself is of no importance to this system; it’s goal is to accumulate money and power, even if that means war, destruction, and the killing of life in all its dimensions. This is the spirit that inhabits us as a society. That is why we say we are in a crisis of civilization, where probably there is no way to stop the train that has gotten off track. Some of us say that we need to struggle for life, to recuperate and dignify ourselves as humanity.

We only have ourselves

In this genocidal war against the Palestinian people, against humanity itself, we are alone. Well, not so alone. It is necessary to know that we only have ourselves. When we realize profoundly that we are important to ourselves and we only have ourselves, those from below, it will be the best weapon to out the brakes on and pull out of the system of death that is destroying us now.

We oppose this genocidal war; which means that we are part of the group of humans that chooses to survive and to put life as the center of our organizations.

* Rocio Moreno: Historian and indigenous Coca defender from Mezcala, Jalisco, interested in showing how life stories are totally linked to the projects that the resistances champion in Mexico, because what are the resistances without the infinite life stories that constitute them?

_________________________________________________

Published by Desinformémonos on November 26, 2023 in Spanish here. Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Information on the war & genocide

‘Worse than the First Nakba’ –Gaza Survivors Speak to the Palestine Chronicle

‘We Dream of Bread’ –An Urgent Appeal from Gaza

Photo: The staggering toll of Israel’s war on Gaza. Here and here.

Photographs of the Israeli destruction of Palestine cultural heritage sites in Gaza.