Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

It’s not War, It’s Genocide!

By Rocio Moreno* | Desinformémonos

The inhabitants of Abya Yala know what genocide is. 500 years ago, with the European invasion in our territories, we not only suffered displacement from our lands, languages and ways of thinking, but also violence and death. According to the demographic historians Borah and Cook, 90% of the native population of what we now call Mexico, died of different causes as a result of colonization. Historians say that the population was reduced but we should begin to name correctly the deaths provoked in the name of war and invasion. What happened 500 years ago was genocide. Since ancient times wars of colonization and imposition have been justified as order and progress, and now 500 years later things have not changed much.

Today, the powerful, the conquerors-invaders continue to advance with the same strategies. What our eyes are perceiving over the past few weeks with the Palestinian people is the same colonizer. When I was a child my mother told me about the fall of Tenochtitlán. I remember that she told me that there were rivers of blood throughout the old city. The scene that I reconstructed in my mind was a place without life; of death, blood, and total destruction of the city. Now we are told that liberty and democracy are virtues given by capitalism and nation states. They also say that our civilization has left savagery behind, that now we are diplomatic. But in reality, there is a profound and subtle violence that justifies the most irrational and schizophrenic acts that we have faced. It is natural for inhabitants of Abya Yala to understand the resistance of the Palestinian people; Palestine is a mirror of our past-present. And from that past, the wounds provoked by that genocide are still here. We know their pain, and many of us feel it too.

Free Palestine!

Understanding the resistance of the Palestinian people for those of us who live in Abya Yala must be almost natural, since it is a mirror of our past-present, and from that past, there are still the deep wounds caused by a genocidal war. We know your pain, and many of us feel it too.

To rise again after a war, a profound wave of violence, with thousands and MILLIONS OF DEAD is nothing easy. In the present context of Mexico, where violence governs our entire country, I often ask myself why haven’t we been able to stop the crisis of civilization that we live every day. Each time I convince myself that surely we are rising up from the genocide of 500 years ago. Since the European invasion we have not been able to leave behind war, crisis, etc.

It pains me that the genocide we are witnessing in Palestine is like what we lived 500 years ago that we still cannot rise above it. We need to look at Palestine from a historical perspective, what is ahead for the Palestinian people, prolonged pain.

They don’t listen to us, they don’t care about us

Not even in public discourse is the war or rather the genocide that we are all witnessing acceptable. However, they still continue to manipulate us and say that this war, which is not a war, but rather a genocide, is justified. They keep telling us that there are overriding reasons to control the rebels. Increasingly, their response is cruder, more cruel and shameless.

Despite this discouraging scenario, hope emerges in different geographies across the planet. The demonstrations, marches, shouts, information forums, etc., have been a sign not only of the solidarity that exists for the Palestinian people, but also a sign that, although there are thousands, millions, of people who speak out against this genocidal war, the powerful do not care about us and are far from listening to us.

Not only across the planet, but among the Israeli people and the United States themselves, there is a rejection of the massacre being carried out on the Palestinian people and they also demand a cease fire. In those moments, the powerful once again show us that they don’t care about us at all. Our lives mean absolutely nothing. How long will we understand that they don’t care about us?

Palestine Unmasks the System of Death

Palestine unmasks the capitalist patriarchal system, and makes visible its horrible intentions against humanity and the entire planet. Ethics, respect, compassion, brotherhood, and life itself is of no importance to this system; it’s goal is to accumulate money and power, even if that means war, destruction, and the killing of life in all its dimensions. This is the spirit that inhabits us as a society. That is why we say we are in a crisis of civilization, where probably there is no way to stop the train that has gotten off track. Some of us say that we need to struggle for life, to recuperate and dignify ourselves as humanity.

We only have ourselves

In this genocidal war against the Palestinian people, against humanity itself, we are alone. Well, not so alone. It is necessary to know that we only have ourselves. When we realize profoundly that we are important to ourselves and we only have ourselves, those from below, it will be the best weapon to out the brakes on and pull out of the system of death that is destroying us now.

We oppose this genocidal war; which means that we are part of the group of humans that chooses to survive and to put life as the center of our organizations.

* Rocio Moreno: Historian and indigenous Coca defender from Mezcala, Jalisco, interested in showing how life stories are totally linked to the projects that the resistances champion in Mexico, because what are the resistances without the infinite life stories that constitute them?

_________________________________________________

Published by Desinformémonos on November 26, 2023 in Spanish here. Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Information on the war & genocide

‘Worse than the First Nakba’ –Gaza Survivors Speak to the Palestine Chronicle

‘We Dream of Bread’ –An Urgent Appeal from Gaza

Photo: The staggering toll of Israel’s war on Gaza. Here and here.

Photographs of the Israeli destruction of Palestine cultural heritage sites in Gaza.

Autonomous region members report a new ORCAO armed attack against BAEZLN in Ocosingo

By Desinformemonos | February 12, 2024

Mexico City | Desinformémonos. Residents of the autonomous region of Moisés & Gandhi, Chiapas, reported a new armed attack against the Support Bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (BAEZLN) by the Regional Organization of Coffee Growers of Ocosingo (ORCAO) this past Sunday night.

The assault with high-caliber weapons began around 8 p.m. on February 11, when members of ORCAO from the town of 7 de Febrero attacked Zapatista territory. There were no wounded reported as of 11 p.m but the shootings continued.

This is a new aggression by ORCAO against the BAEZLN of Moisés & Gandhi, which on January 19 recorded the forced displacement of 28 Zapatistas, including ten girls and boys, from the La Resistencia community due to the violence of the paramilitary group in the region.

“The aggressions of the ORCAO towards the EZLN have been a constant in the Moisés & Gandhi area, which has caused a continuity of serious violations of human rights in the region such as forced displacement, torture, forced disappearance and attempted homicides,” emphasized the National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” (TDT Network, Red Nacional de Organismos Civiles de Derechos Humanos “Todos los Derechos para Todas, Todos y Todes”) in the statement on the displacements in January of this year.

The forced displacement on January 19 was the result of two days before, around 40 members of ORCAO arrived with firearms, machetes and sticks to La Resistencia, where they destroyed the Autonomous Primary School and 15 houses made of tin and wood, and burned the books of the education promoters, robbed a store, destroyed nearby crops and threw away stored food such as maize, beans, coffee and sugar.

The organizations that make up the TDT Network denounced “the permissiveness and compicity of the Mexican State” in the face of violence against the autonomous territories and stressed the urgency for the federal and Chiapas governments to carry out an “immediate and diligent” investigation that leads to ending “this climate of violence.”

With information from La Jornada.

______________________________________

Published by Desinformemonos on February 12, 2024 available here. Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Photo by Desinformemonos. Banner reads: No more paramilitaries in Zapatista communities.

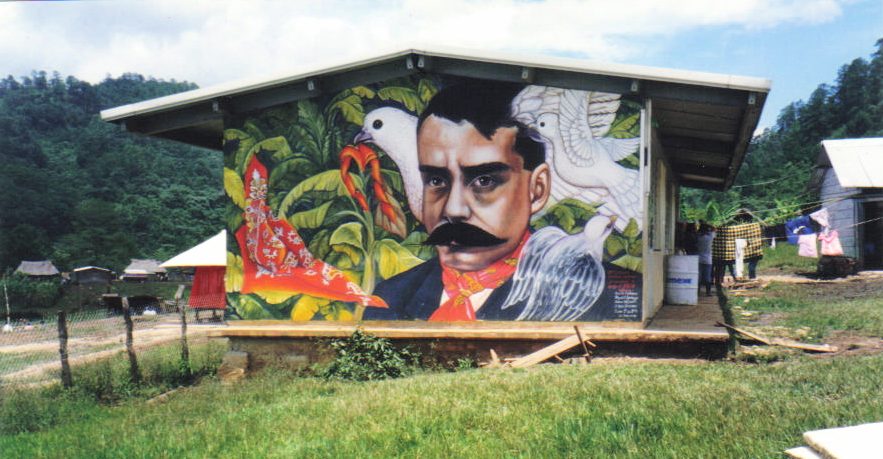

Art as revolutionary weapon: Reflections from Zapatista territory.

By the Observatorio Memoria y Libertad

The most powerful ammunition of the Zapatistas are their bullets of verses, theater, and music; poetry. It is enough to read their proclamations, their proclamations, communiques and stories to confirm it.

A struggle against capitalism is won more easily when the first purpose of the insurgents is to open consciences; awaken people to the ominous reality that this capitalist hydra will continue to devour, without mercy, everything in its path.

Real bullets have never worked; they have wasted the blood of youth, childhood, of women and men who succumb to lead, to its cold.

Verse, music, dance, theater and colors will, therefore, be ammunition to defeat that hydra and, at the same time (and completely), not let that flower, the flower of the word, die; the one with old roots.

Zapatista art is an example of oratory, a rhetoric that comes out naturally, in an organic way. And being in Zapatista territory is, in itself, poetic.

Clouds pouring between the mountains like waterfalls; starry nights like nowhere else; a Mayan past, ancestral native languages; a fight for freedom; a fight against capitalism and death and destruction, all of that is a formula, one that creates rhetoric; In every look of every insurgent there is a metaphor, a mirror, a simile, like a heart on fire.

If to all this mystical nature, if to all this fantastic and rebellious everyday life, we add a good sense of humor, good comedy, what Juan Villoro calls the “rebellious condition of laughter,” we obtain ammunition, bullets, poetic weapons, joyful rebellion; a very happy rebellion, worthy of the use of irony. Let’s take as an example the phrase “sorry for the inconvenience, this is a revolution,” a phrase reproduced during the armed uprising of the war against oblivion in 1994.

When we add revolution to art, we obtain consciousness; we get another way to fight; This is how the compas show us, this is what old Antonio would tell us, perhaps, the one who, with stories of the grandparents, the first who made the world, reveal the Zapatista traditions, or like the beetle as shield bearer and battle advisor, Don Durito, who accompanies the Zapatista struggle and will accompany it until freedom is achieved.

As the afternoon went on, plays produced by the children of the different Caracoles were presented in the center of the enormous dance floor. Theatrical works with completely critical and humorous plots, with social, political and cultural plots and that, immersive, carried a criticism focused on the conscious. Artistic and critical childhoods, who, without hesitation, recited their lines one by one and without any fear, represented their characters.

Plays whose theme included the labor exploitation of the land-owners towards the laborers; the so-called projects of death and destruction carried out by bad governments; satires of the different presidents and their cynical attacks on life and liberty.

The afternoon continued, and the children continued teaching artistic expression, not only with theater, but also with dances, full dances in which the dance was syncretized with the historical representation of the Zapatista struggle.

Those who will guide the future and trace the paths will be the children and youth; and, looking at these plays that were not only beautiful in the aesthetic and technical sense, they were critical. Boys and girls between the ages of 5 and 15, staging works in which the Zapatista struggle, the corruption of bad governments and projects of death and destruction were represented, is without a doubt a light of hope within the EZLN struggle. Zapatista childhoods are shared, they are intelligent, critical and rebellious, worthy rebels.

The Zapatistas have always fought with language as a weapon, with poetry and verses like bullets, with murals as expressions and ways to immortalize their history and their struggle.

Just read their communiques; their statements; their stories; poems, with seeing their plays and witnessing the Zapatista dances. It is enough to dance among militiawomen and militiamen who smile with joyful rebellion.

Art is the most powerful, least violent and most human weapon, to fight, defend and resist in the battle for the liberation of the earth and those who work on it.

_____________________________________________

Published February 2, 2024 by Observatorio Memoria y Libertad at: https://memoriaylibertad.wixsite.com/inicio/post/del-arte-como-fusil-revolucionario-reflexiones-desde-territorio-zapatista Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Chiapas: Armed group displaces Zapatista community La Resistencia

by Elio Henriquez, La Jornada correspondent | February 3, 2024

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas. The National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” (Red TDT, Red Nacional de Organismos Civiles de Derechos Humanos Todos los Derechos para Todas, Todos y Todes), reported that 28 support bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), were forcibly displaced from the autonomous community of La Resistencia, located in the Moisés and Gandhi region, in the official municipality of Ocosingo, “by more than 40 members of the Ocosingo Regional Coffee Growers Organization (ORCAO), who carried firearms, machetes and sticks.”

In an “urgent action” communique, they said that “during the attack, the autonomous primary school and 15 houses made of tin and wood were destroyed, in addition to ‘books belonging to education promoters being burned and a store robbed.’”

They added: “The community was stripped of various material goods: backyard animals, work tools, a coffee pulper and presses for making tortillas,” apart from the fact that the attackers “destroyed nearby crops and threw away stored foods such as corn, beans, coffee and sugar”.

The urgent action also noted that “according to the information received, on January 17, 2024, the community was threatened. The attacking group arrived at the Zapatista town of La Resistencia, carrying sticks and machetes. At this moment they stated that the Zapatista bases had two days to abandon their homes.”

The Red TDT stated that “in the same region, on January 19, 2024, 54 people from the ORCAO from the town of Sacrificio La Esperanza came to burn a pasture of the EZLN bases in the town of Emiliano Zapata, leaving the grazing animals without food.”

The Red TDT expressed “concern about the permissiveness and overlap of the Mexican State,” since, “based on information received in this office, we document that on January 14, 2024, the municipal councilor of Ocosingo inaugurated an ORCAO municipal agency in the space stripped from the Zapatista bases in November 2021, where the Zapatista Arcoíris collective store was located at the Cuxuljá highway junction.”

They recalled that “the aggressions of the ORCAO towards the EZLN have been a constant in the area of Moisés and Gandhi, which has caused a continuity of serious violations of human rights in the region such as forced displacements, torture, forced disappearance and attempted homicides.”

Red TDT commented that “on May 5, 2022, the La Resistencia community was forcibly displaced in a similar attack, reported by this organization. On May 23, 2023, Jorge López Sántiz, a Zapatista support base, a neighbor of Moisés and Gandhi, was the victim of an armed attack that put his life at serious risk.”

The Network demanded that the federal and state governments “guarantee respect for the territory of the Zapatista bases, their free determination and autonomy, as well as a life free of violence; “that an immediate and diligent investigation be carried out to generate a route that prioritizes ending this climate of violence and adopting actions aimed at repairing the damage and initiating a justice process” in favor of the 28 displaced people, including ten girls and boys.

_______________________________________________

Published in Spanish on-line by La Jornada on February 3, 2024 and translated by the Chiapas Support Committee. Read the original here: https://www.jornada.com.mx/noticia/2024/02/03/estados/en-chiapas-grupo-armado-desplaza-a-comunidad-zapatista-a-resistencia-8321

The Chiapas Support Committee invites you to take urgent action in solidarity with the EZLN support bases that were forcibly displaced by the rightwing violence. The Red TDT petition, “Forced displacement of 28 Zapatistas in the Moisés and Gandhi region,” is in Spanish. Click here to sign the Red TDT urgent action alert: https://redtdt.org.mx/archivos/18769?fbclid=IwAR2diVLc_LNLROZgqroExHmTUt91yF-0l0wZMhX85ruozypKcXq1iau7-sI

West Coast premiere of new zapatista film: La Montaña

Please join us to view La Montaña, the new documentary on the Zapatista voyage to Europe, by Diego Enrique Osorno.

- Friday, January 26, 7-9pm, at the Eastside Arts Cultural Center (located at 2277 International Blvd. Oakland, CA 94606) and

- Sunday, January 28, 6-9 pm at the Tamarack (1501 Harrison Street,Oakland CA 94612).

- The gatherings will include guest speaker: Rocío Moreno, member of the Coca community in Mezcala, Jalisco, and updates & dialogue/discussions and reflections on the film and the Zapatista movement.

Released in 2023, La Montaña provides an intimate view of the journey for life that the Zapatista 4-2-1 squadron initiated in 2021 on the dilapidated sailing ship, christened La Montaña (the mountain) by the EZLN. The film follows the Zapatistas as they cross the Atlantic from Mexico to Europe to meet with their grassroots counterparts.

From the filmmaker:

“A film log of the maritime journey of a delegation of indigenous rebels from Chiapas to Europe in the midst of the pandemic. During the Atlantic crossing, the story and generational change of the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) is narrated, based on the idea that in order to change the world we must first change the way we look at it.”

—Diego Enrique Osorno

BACKGROUND

La Montaña documentary film shows the story of the Zapatista Journey for Life, on a sailboat from Mexico to Europe, to commemorate in a new way the 500th anniversary of the European invasion of Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City), when Spaniards laid siege to the Indigenous capital on August 13, 1521.

La Montaña begins in Zapatista territory and follows the 4-2-1 Squadron, the EZLN delegation, as they board a dilapidated and rusty sailboat, christened La montaña by the Zapatistas. The Zapatistas launch La montaña from a Gulf coast port in Mexico to start their sea voyage across the Atlantic. Weeks later, La montaña reaches a sea port in Vigo, Spain, greeted by community organizations and activists. When the 4-2-1 disembarks, led by Marijose, they declare and rename Europe “Slumil K’ajxemk’op,“ which means “Rebellious Land,” or “Land that does not resign, that does not faint.”

The 4-2-1 squadron, composed of four women, two men, and one they/them, entered Madrid, Spain’s capital city, exactly 500 years later on August 13, 2021, not to lay siege but to walk together with those who struggle to learn from each other’s movements against the hydra-headed capitalist system. The EZLN delegates to Slumil K’ajxemk’op connect in new and different ways to band together in a worldwide journey for life, a new movement for peace, land, justice, self-determination and liberations.

The EZLN’s 4-2-1 squadron came to Spain first and were later joined later by air-borne Zapatista delegations, who traversed the rest of Europe, from west to east, to engage in both listening and dialogue sessions with their grassroots counterparts.

Please join us January 26 and 28 to view La Montaña and join together in the ongoing Journey for Life, walking together to build and strengthen our communities with more dreams and organizing for justice and liberation.

Palestinians & Zapatistas: Extremes that come together in the fight against inhumanity

By Pietro Ameglio | Originally published by Desinformémonos in Spanish.

For this article we will take as a basis the textual words chosen from particularly significant moments, of Palestinian and Zapatista protagonists about their struggles, challenges and sufferings, since they seem to us in this case stronger and more effective than any other reflection.

1. Palestinian genocide in Gaza: Moral Compass of humanity

We return to the question in the title of our previous article in this medium (in Spanish at https://desinformemonos.org/por-que-el-papa-y-el-patriarca-ortodoxo-junto-a-lideres-rabinos-e-imanes-no- are-accompanying-with-their-bodies-today-Palestinian-and-Israeli-families-in-Gaza/ ): why have the Pope and religious leaders of Judaism, Islam and other traditions not yet gone to “place their body” in Gaza, alongside Palestinian families? It is a brutal snapshot of the level of growing inhumanity that affects our species. It shows the lack of a living incarnation with the victims on the part of the leaders of religious traditions, unlike their people and faithful believers who have carried out numerous acts of solidarity. And also of the helplessness, with little voice in key decisions and the lack of challenges in the most radical nonviolent action of the people of God in those religious traditions, where we are not capable of making — as the Zapatistas would say– the authorities “lead by obeying” the people, and do what the sacred words of their texts say unambiguously: Put their bodies next to the victims “until they give their lives for them.”

Regarding the impossibility of risking nonviolent actions that “oblige” our religious hierarchs to fulfill “their duty,” a passage from the Gospel comes to mind (Mc. 2, 3-5), where relatives of a sick person, seriously ill such he could not go to Jesus Christ in his public healing meetings to be cured, had to take him up to the roof of a house where Jesus was. Then they lowered him through the roof so that he could see him and cure him, which is what happens. It seems to me, in all ignorance and simplicity, but also with audacity and humility, that this evangelical story could give us a clue about how we should act nonviolently so that the Pope and other religious hierarchs “land” -yes or yes!- in Gaza, even if it had to be removing rubble.

Father Donald Hessler, whom I have cited more than once in this medium as an example of nonviolence, used to ask people to question the type of faith they had in their lives: “Where do you want to die: in bed?” or on the cross?” It is the question that should be asked at least to the Pope and the Christian religious heads now regarding this genocide. In the only passage of the gospel where Jesus refers to the Last Judgment – something that goes beyond any religious belief, it seems to me – he calls himself “Son of Man” (not of God), and clearly indicates what the measure will be. with which our life will be measured: “I was hungry and you fed me, I was thirsty, I was imprisoned, naked… (Mt. 25, 31-46)”… I was bombarded. As we have said, it is not about seeking any form of gratuitous martyrdom but about embodying the Word of God and the will of the people suffering from him, which is the only thing that justifies exercising that religious power.

For a few days now, a video has been circulating on the networks about a homily (“Christ under the rubble”) by the Palestinian Lutheran pastor Munther Isaac, made in Bethlehem the day before Christmas (https://www.youtube.com/watch ?v=CjIG2YZBXpo&ab_channel=PEAPIECUADOR See links below.), which seems to me to be very strong, profound and clear regarding this issue and the current emergency of humanity, with which we are in full harmony since our previous articles.

The pastor begins by saying that “Gaza as we knew it no longer exists. This is annihilation. It is a genocide. The world watches, the churches watch. The people of Gaza send live images of their own execution … We are tormented by the silence of the world. Leaders of the so-called ‘free world’ are lining up to give the green light to the genocide of a captive population.” And he adds: “If you are afraid to call it genocide, it is your responsibility, it is a sin and it is darkness that you voluntarily welcome.”

This political sphere is complemented by another, which is the cover-up of “theological protection” by Western churches; In South Africa the concept of “state theology” was created: theological justification of the status quo of racism, capitalism and totalitarianism. In Palestine “we confront the theology of the Empire that masks oppression under the cloak of divine decrees: it speaks of a land without people, it divides people between ‘them’ and ‘us’. It dehumanizes and demonizes… calls to empty Gaza (go to Egypt, Jordan… to the sea).” And he continues to question the theology of the Empire, asking: “How does the murder of 9,000 Palestinian boys and girls amount to self-defense? How is the displacement of 1.9 million people, the murder of more than 20 thousand Palestinians, self-defense? They transform the colonizer into a victim and the colonized into the aggressor.” And he adds that it is evident that “The world does not see us as equals… If 100 Palestinians have to be killed to hunt down a Hamas militant, then go ahead. They don’t see us as humans. In the eyes of God, no one can take away our humanity.”

Pastor Munther says that the genocide in Gaza “has become the moral compass of the world today” (of the current moral state of humanity). And he continues to reflect self-critically: “If you are not horrified by what is happening in Gaza… there is something wrong with your humanity. If as Christians we are not outraged by genocide and the use of the Bible to justify it, our Christian witness is distorted.” He then adds that “We are outraged by the complicity of the churches. Let’s be clear: silence is complicity. An empty call for peace without demanding a Ceasefire and End to the Occupation, and superficial empathy without direct action, all of this is complicity.”

He also wonders, remembering how Jesus was displaced by the empire and had to flee to Egypt – just like the Palestinians today -, what Jesus exclaimed with great pain on the cross: “My God, why have you abandoned me?” And he answers that through the supportive people, nearby, they know that God has not abandoned them, He is among the rubble there: vulnerable, displaced, refugee. That is precisely where the Incarnation is: “we see it in every murdered boy and girl…in every displaced family wandering around in despair without a home.”

Finally, the pastor concludes with a message to the world: “This Genocide Must Stop Now!” And he adds that the Palestinians, as they have always done, will rise up and continue fighting; however the moral problem will lie with the rest of us who may have been complicit in our silence: “Look in the mirror and ask yourself: where was I when Gaza was passing through a genocide?”

This resistance and permanent moral and material strength in their bodies to fight against inhumanity and injustice deeply unites the Palestinian people with the Zapatistas.

2. Zapatismo: 30 years of building humanity and a profound “common root” change

Zapatismo has been much more than a great and heroic revolution of a people in arms in a very specific, mainly indigenous Mayan territory of the Mexican southeast. It has also been more than an enormous, original and inspiring global phenomenon of cultural, social, economic and political resistance against neoliberalism and for humanity. There is also an unobservable social long-term history: A humble and very concrete advance, totally real, of the millennia-long process of humanization of our species. An important community in number within a certain territory – also large – is trying – with very precise results and also limitations – to build a model of community life from the principles of equality and community co-operation, non-capitalist as much as possible. There are no more examples and results – not even close in quantity and quality – in universal human history, for a similar number of bodies and territory, with that temporality and continuity.

How is the structural reorganization of Zapatista autonomy proposed today?

The EZLN in the last and twentieth part communiqué from a few days ago, titled “The Common and Non-Property,” delves into the explanation about a “new stage that the Zapatista communities have decided:” “Let’s say that the first 10 years of autonomy, that is, from the uprising to the birth of the Good Government Boards in 2003, was a learning experience. The next 10 years, until 2013, were about learning the importance of generational change. From 2013 to date it has been about confirming, criticizing and self-criticizing errors in operation, administration and ethics.”

In November of last year they had already advanced the main points of their decentralized political structural reorganization of the autonomy project, in their IX part of their communiqué (“The new structure of Zapatista autonomy,” where they pointed out that the base would be the Local Autonomous Governments (GAL): “There is a GAL in each community where the Zapatista support bases live. The Zapatista GAL are the core of all autonomy. They are coordinated by autonomous agents and commissioners and are subject to the assembly of the town, ranchería, community, area, neighborhood, ejido, colony, or however each population calls itself. Each GAL controls its autonomous organizational resources (such as schools and clinics) and the relationship with neighboring non-Zapatista sister towns. If before there were a few dozen MAREZs, that is, Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities, now there are thousands of Zapatista GALs…” and they also address all forms of corruption that may arise.

In turn, according to the reality of the area, “several GALs convene in Zapatista Autonomous Government Collectives, CGAZ, and here they discuss and make agreements on matters that interest the GALs that gather. When they so determine, the Collective of Autonomous Governments calls an assembly of the authorities of each community. Here the plans and needs of Health, Education, Agroecology, Justice, Commerce, and those that are needed are proposed, discussed and approved or rejected… Each region or CGAZ has its directors, who are the ones who call assemblies if there are any “an urgent problem or one that affects several communities…that is to say, where before there were 12 Good Government Boards (JBG), now there will be hundreds.”

On another scale, there are “the Assemblies of Collectives of Zapatista Autonomous Governments (ACGAZ), which are what were previously known as zones. But they have no authority, but depend on the CGAZ, and the CGAZ depend on the GAL. The ACGAZ convenes and presides over zone assemblies, when necessary…They have their headquarters in the caracoles, but they move between the regions.”

In this way, in this profound political and social change towards a process of decentralization and more direct control of power and decisions from the community bases and their assemblies, “the Command and Coordination of Autonomy has been moved from the JBG and MAREZ to the towns and communities, to the GAL. The zones (ACGAZ) and the regions (CGAZ) are governed by the people, they must be accountable to the people and find a way to meet their needs in Health, Education, Justice, Food and those that arise due to emergencies caused by disasters. natural disasters, pandemics, crimes, invasions, wars, and the other misfortunes that the capitalist system brings.”

What will the Common and Non-Property be like?

In the very recent communiqué-part number XX (“The common and Non-Property,” they explained that the aim will be to “establish the extent of the recovered land as common land. That is to say, without property…without papers…of ‘nobody’, that is, ‘of the common’.” To achieve such revolutionary advance in its social order and community organization, in terms of the ownership of the land, its use, work and the social relations between those who occupy and work on it, “there must be an agreement between the residents regardless of whether they belong to a party or are Zapatistas…that they work together in shifts.”

Why did they come to this decision to face the current “storm,” which is one of survival?

The reasons are varied: “nature’s dissatisfaction” with current exploitation; “breakdown of the social fabric because of violence;” the capitalists “don’t care what happens tomorrow;” “Western civilization” only brings wars and crimes.

How did you build the knowledge necessary for this new path?

For years, a community process developed, from the elders and collective memory, where “We remember how it was before… and we saw that (the storm) came with private property… in all cases it is the bad government that issues the papers.” The farmers have to go out of their way to obtain their papers and apparent property rights, fighting among themselves, violently dividing families, being subjugated and deceived by chiefs and parties… all for a fucking piece of paper.” And they add how natural resources are a commodity “as were your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents… as you are, and your children will be.” This new approach questions at its roots one of the main bases of the capitalist system, such as private property, and the entire machinery of its apparatus and legalistic bureaucracy, which largely starts from a “fetishization” of the signature and paper, rather than the recognition of justice and social equality.

What will the “material base” be like in this new stage of the common?

Individual-family work (small personal property) will be combined with collective work (the land belongs to a collective) -existing until now- and what is now proposed as work in common or non-property: “A portion of the land recovered is declared as ‘common work’. That is, it is not parceled out and is not owned by anyone…according to the nearby communities, they mutually ‘loan’ that land to work on it. It cannot be sold or bought. It cannot be used for the production, transfer or consumption of narcotics. The work is done in ‘shifts’ agreed upon with the GALs and the non-Zapatista brothers and sisters. The benefit or gain is for those who work, but the property is not, it is a non-property that is used in common.”

What do the young generations say about the new change in their autonomous revolutionary process?

In the recent celebration of the 30 years of the uprising in Caracol VIII of Dolores Hidalgo, they reflected – amidst group music – young people born free, new generations built in these decades through autonomy projects, self-government… especially in areas of health, education, good government, production and food…We share here verbatim some phrases that we consider significant to understand this revolutionary social process in the Zapatista lands of Chiapas: “Today 30 years later, let us be the guardians of Mother Earth, make this world the sharing of working the land and water in a common way…We will leave them a better life for the future of our generations. We and you sow life, together we will reap life together.”

And going deeper they added: “The community is the wisest inheritance that our grandfathers and grandmothers left. In the community we are everything and without the community we are nothing…Unity has made us resist. With organization we advance in autonomy, we can destroy those who oppress us.” And in turn, “I, Mother Earth, belong to everyone and for everyone, I am not anyone’s property. New is life in common, where the master and the boss do not exist.”

Likewise, regarding autonomous education, they pointed out that: “Between the shadows of the giant trees, between wind and heat, among the mountains a volcano of imagination is made, this is how education is born…Boys and girls already prepared for a decade, we look for another way and we find it. It’s time to form a story of no return. Build now a new way of educating ourselves together…We are the men and women of Mayan roots, we are the ceiba of history…we long for a dream of another tomorrow without distinctions.”

Towards the end, a young man recited a very significant poem about the current struggle titled “It is not a time to cry:”

This is not the time to cry…

It’s time to wake up and prepare together

It is time to jointly challenge the main enemy

It is time for unity and saving humanity

It is time to cultivate and defend mother earth

It is time to resist and rebel against the great storm that we are going to face.

___________________________________________________________

Translated from the Spanish by the Chiapas Support Committee. Published originally in Desinformémonos here.

VIDEOS

From the sermon: Christ Under the Rubble (full service; clip from the Sermon)

Defend life to the rhythm of a cumbia

By Mariana Mora | Originally published in Spanish by La Jornada

Over the course of three decades, Zapatismo has managed to break through again and again into what appears to be the inevitable destiny of a historical outcome. Just when everything seems to be firmly agreed between those who cling to power and exercise violence, the rebel army and its support bases act in such a way that political inertia takes an unexpected turn. They cause exhaust leaks that bypass dead ends. At the same time, instead of predetermining the course of these counterstories, they cultivate conditions of openness. That is in part due to the transcendence of Zapatismo and its continued relevance. The commemorative gathering that was held between December 30, 2023 and January 2, 2024 activated that characteristic capacity of theirs.

The state of Chiapas, like the rest of the country, if not the world, is going through extremely complex terrain. On top of long-term colonial violence, layers of paramilitarism, organized crime, extractivist policies and development megaprojects are being heaped on. These generate landscapes criss-crossed by territorial dispossession, forced displacement and socio-environmental destruction. Faced with a highly constrained scenario, the commemorative events in the Dolores Hidalgo caracol, instead of responding to the situation, transcended their limits.

The speech given by Subcomandante Moisés ignored the electoral context, the proposals of the pre-candidates for the federal Presidency and state government, he avoided naming the actors who activate violence in the country. The commemorative event took on another meaning, it extended towards a horizon marked by the dignified life of Dení, that girl who will be born in 120 years, the protagonist of the third part of the series of communiques published by the EZLN between October and December 2023.

Acting from the possibilities of life to seven generations requires reinventing how the actions of a rebel army manifest themselves in the present. If its function is to defend life-existence in common, this is achieved, not by showing off a political muscle, nor by provoking a fight between roosters, but at the rhythm of a cúmbia. The militiamen marched, with the discipline that all military training requires, to the songs of Los Ángeles Azules and Celso Piña. From this same impulse the militiawomen danced the ska of Panteón Rococó. This is how collective vitality is cared for in scenarios saturated by the presence of the security forces of the Mexican State, the private armies of organized crime and the paramilitaries. It is an antidote to genocide.

At the end of the music, Subcomandante Moisés ordered from the stage: Shield formation! The hundreds of militiamen formed a circle that they asked everyone to enter: first the support bases, followed by the visitors. In that expanded space of protection they wrapped us in enough air to breathe their invitation to seek and build the sense of commonality among everyone.

The common was the central concept in which the commemoration rooted the future. The common adds dimensions and densifies the exercise of autonomy over the last 25 years. The common is not established through property, not even collective property, but it is no one’s territory because it belongs to everyone, such as the lands recovered after the 1994 uprising. Collective belonging and socio-natural relations are woven by through the relationships that care for and sustain life-existence. They require active and constant participation outside the State and its institutions. The common is in turn the meeting space. It manifests itself in the cross stitches of an embroidery in which the threads come together without any of them being subsumed or hidden among the others. What is the common is the web of threads capable of supporting much more than its own weight. Subcomandante Moisés referred in Tseltal to the dignified existence of life, to the lekil kuxlejal, and to the land that in turn is the people and is the whole, expressed through lum k’inal. They are the elements that his grandparents and great-great-grandparents have defended, elements that constitute that basis of what is common in Mayan territory. They are in turn a reference to creating the common from one’s own and linking various geographies.

The set of steps marked by the cúmbia, the embrace of the militia circle and the interpellation of the common produced an essential turning point in the face of current extreme violence. The common further distances the rebel army from the revolutionary genealogies that gave rise to it, transforming how that revolution is created. Perhaps it is one of the results of the internal critical reflection in which the EZLN and its support bases have been immersed in recent years.

The Zapatistas do not solve the challenges we face now. They offer more questions than answers. The tasks are immense, the path extensive. The guide is the book of living memory of those who were absent, including those who fell 500, 40 and 30 years ago. In his speech, Subcomandante Moisés insisted that although poetry, painting and art are important, they are not enough. The important thing is the action. But in this case, it is precisely the poetic embodied in the commemorative acts that allowed us to glimpse the possible in order to transcend the limits imposed by the present.

______________________

Mariana Mora is a professor and researcher at the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology (Ciesas, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social) and author of the book Kuxlejal Politics: Indigenous Autonomy, Race, and Decolonizing Research in Zapatista Communities

“Defend life to the rhythm of cúmbia” was translated by the Chiapas Support Committee from the Spanish. Originally published by La Jornada here, January 6, 2024: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2024/01/06/opinion/010a1pol

The Common: the new horizon

By Raúl Romero | Published in Spanish in La Jornada here.

The journey has been long. Due to battered and privatized roads, we are running into sections under repair and accidents. The driver of our vehicle says: “You have to drive carefully, the devil is loose.” A trip that takes 14 hours, from Mexico City to San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, we do it in 21 hours.

The climate of violence in the country, that devil that has been unleashed since 2006, leads us to take all precautions: We leave a list with emergency contacts and a group monitors our trip from fixed locations. Every four hours they receive our location. If no report comes, they look for us. If they do not find us within a certain amount of time, they have to notify Frayba or the TDT Network, the independent organizations that accompany the “National and international Caravan to Zapatista territory.” No precaution is less necessary to cross this painful country and its geography of terror.

Then comes the second leg of the trip, from San Cristóbal de las Casas to the Caracol “Resistance and Rebellion: A New Horizon,” in the town of Dolores Hidalgo, a little more than an hour from Ocosingo. Here the dilemma is which route to take: the one that is usually taken by paramilitary groups and that charges a “right of way” fee, that has sections with landslides, or the longest one and full of curves. There is no discussion. We take the curvy road, some take dramamine, and we begin the journey.

Four and a half hours later, with pale faces and some stomachs emptied along the way, we arrive in rebel territory. We send the last report: “We have arrived.” In Zapatista territory we are not in danger. At the entrance to the Caracol, the compas – as we affectionately call the Zapatista people – have placed several banners from previous events such as the “dance-share,” “the women with rebel dignity”, “the capitalist hydra” . . .

The entrance becomes a collective hug, hundreds of people traveling from different parts of the world meet again in Zapatista territory. The conversations last for hours. Hearts are happy. Collective projects begin to be planned. Diagnoses generate debates. Palestine and Kurdistan are present in the talks. New alliances are forged. The great network of global solidarity that is articulated around the EZLN is strengthened.

The celebration of 30 years of the war against oblivion is also the celebration of a new stage of internationalism. At the Caracol you meet the protagonists of the Zapatista movement. Marijosé, the compañeroa who more than two years ago traveled on the ship La Montaña from the Mexican southeast to Europe – and renamed it “Unsubmissive Europe” – now fulfills a new assignment: they are in charge of the kitchen that will feed the thousands of people.

Verónica, Chinto, Amado and other prominent members of the Palomitas Command – reinforced with new members such as Remigio – also roam around the Caracol. They ride dragons, unicorns and other fantastic creatures. Their laughter and pranks, one of the secret weapons with which Zapatismo seduced Rebellious Europe, now also call for hope.

A friend comments: “Zapatista territory is the only place where I do not have to keep my eyes on my daughters and I feel calm.” This is one of the objectives of Zapatismo: a world where a girl can play without fear. If in the past, theater and pastorelas were used in order to evangelize indigenous communities in the “new world,” today the Zapatista indigenous communities subvert their function and make theater a tool to pedagogically explain an extremely complex process: its history, the war against oblivion, leading by obeying, the autonomous Zapatista rebel municipalities, the councils of good government and what is its new horizon, the common and non-property.

On December 31, at 11:30 p.m., the EZLN shows its strength and organization. Thousands of militiamen, men and women, perform exercises to the rhythm of cumbia and ska. The message is clear, Zapatismo is an army that has chosen life, but is willing to defend its territories and project.

Contrary to what intellectuals, “specialists” and journalists forged in “lazy thinking” say, Zapatismo is full of youth. Among militiamen and militiamen, the faces and bodies of those who are beginning to leave adolescence behind can be seen. A new generation of Zapatistas and a new stage of Zapatismo. “The property must belong to the people and be common, and the people have to govern themselves,” says Subcommander Moisés, spokesperson for the EZLN, in his speech. Sketches that manage to draw the new theoretical and political horizon launched by the Zapatistas. 30 years after the war against oblivion, Zapatismo embarks towards the future of humanity.

* Sociologist @RaulRomero_mx

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee from the original in Spanish; published January 7, 2024 in La Jornada: https://www.jornada.com.mx/noticia/2024/01/07/opinion/el-comun-el-nuevo-horizonte-5412

EZLN: Fourteenth Part & Second Approach Alert: The (other) Rule of the Excluded Third Party.

Fourteenth Part and Second Approach Alert: The (other) Rule of the Excluded Third Party.

The meeting was a year ago. One early morning in November. It was cold. Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés arrived at the chambers of the Captaincy (yes, you are not wrong, by that time SupGaleano had already died, it was just that his death had not been made public). The meeting with the jefas and jefes [the main leaders] had ended late, and SubMoy took time to stop by and ask me about what he had done in the analysis that had to be presented the next day at the assembly. The moon was moving lazily towards its first quarter and the world population reached eight billion. Three notes appeared in my notebook:

The richest man in Mexico, Carlos Slim, to a group of students: “now, what I see for all of you is a buoyant Mexico with sustained growth, with many opportunities for job creation and economic activities” (November 10, 2022). (Note: Perhaps it refers to Organized Crime as an economic activity that generates employment. And with export goods).

“(…) the number of people who are currently reported missing in Mexico, since 1964, now amounts to 107,201; That is, seven thousand more than last May, when the 100 thousand threshold was exceeded. (November 7, 2022). (Note: Look for the search engines).

In Israel, the UN put the number of Palestinian prisoners at around 5,000, including 160 children, according to the report by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967. Netanyahu takes over as head of the government for the third time. time. (November 2022). (Note: He who sows wind will reap storms).

-*-

A crack as a project.

It was not the first time we had discussed the topic. What’s more, the last few moons had been the constant: the diagnosis that would help the assembly make a decision about “what’s next.” They had also been discussing this for months, but the idea-proposal of Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés has not just landed or materialized. It was still a kind of intuition.

“It’s not that all the doors are closed,” I began. – There are no doors. All those that appear as “true” do not lead anywhere other than to the starting point. Any attempted route is just a trip through a labyrinth that, at best, takes you back to the beginning. At worst, to disappearance.

So? SubMoy asked, lighting the umpteenth cigarette.

Well, I think you’re right, all that remains is to open a crack. No longer looking for him elsewhere. You have to make a door. It’s going to take time, yes. And it’s going to cost a lot. But yes, it is possible. Although not just anyone. What you are thinking, no one, ever. I myself didn’t think I would even hear it – I pointed out.

SubMoy remained thoughtful for a while, looking at the floor of the champa, full of cigarette butts, tobacco residue from the pipe, a burnt match, wet mud, some broken twigs.

Then he got up and, heading to the door, he only said: “Well, no way, we need to see… what’s missing is missing.”

-*–

Failure as a goal.

To understand what that brief dialogue meant, I must explain a part of my job as captain. In this case, a work that I inherited from the late SupGaleano, who in turn received it from the late SupMarcos.

A thankless, dark and painful task: foreseeing the Zapatista failure.

If you are considering an initiative, I look for everything that could make it fail, or, at least, reduce its impact. Look for the contradictory opposite. Let’s say something like “Marcos Contreras”. I am, therefore, the maximum and only representative of the “pessimistic wing” of Zapatismo.

The objective is to attack the initiatives with all types of objections from the moment they begin to be born. We suppose that this causes this proposal to be refined and consolidated, be it internal organizational, be it external initiative, be it a combination of these two.

To put it clearly: Zapatismo is preparing to fail. That is, imagine the worst scenario. With that horizon in perspective, plans are drawn up and proposals detailed.

To conceive these “future failures”, the sciences that we have at our disposal are used. You have to look everywhere (and when I say “everywhere” I mean everywhere, including social networks and their bot farms, fake news and the tricks that are carried out to get “followers”), obtain the greatest amount of data and information, cross it and thus obtain the diagnosis of what the perfect storm would be and its result.

They must try to understand that it is not about building a certainty, but rather a terrible hypothesis. In terms of the deceased: “suppose everything goes to shit.” Contrary to what one may believe, this catastrophe does not include our disappearance, but something worse: the extinction of the human species. Well, at least as we conceive it today.

This catastrophe is imagined and we begin to look for data that confirms it. Real data, not the prophecies of Nostradamus or the biblical Apocalypse or equivalent. That is, scientific data. Scientific publications, financial data, trends, records of facts, and many publications are then used.

From this hypothetical future, the clock starts in reverse.

-*-

The rule of the excluded third.

Already in possession of the drawing of the collapse and its inevitability, the rule of the excluded third begins to work.

No, it is not the known one. This is an invention of the late SupMarcos. When he was a lieutenant, he said that, in the event of a failure, a solution was first attempted; second, a correction; and third, since there was no third, it remained as “there is no remedy.” Later he refined that rule until he reached the one I now present to you: supported by a hypothesis with true data and scientific analysis, it is necessary to look for two elements that contradict the aforementioned hypothesis in its essence. If these two elements are found, the third is no longer sought, then the hypothesis must be reconsidered or confronted with the most severe judge: reality.

I clarify that, when the Zapatistas say “reality,” they include their actions in that reality. What you call “practice.”

I then apply that same rule. If I find at least two elements that contradict my hypothesis, then I abandon the search, discard that hypothesis and look for another one.

The complex hypothesis.

My hypothesis is: There is no solution.

Notes:

Balanced coexistence between humans and nature is now impossible. In the confrontation, the one who has the most time will win: nature. Capital has turned the relationship with nature into a confrontation, a war of plunder and destruction. The objective of this war is the annihilation of the opponent, nature in this case (humanity included). With the criterion of “planned obsolescence” (or “expected expiration”), the commodity “human beings” expires in each war.

The logic of capital is that of greater profit at maximum speed. This causes the system to become a gigantic waste machine, including human beings. In the storm, social relations are disrupted and unproductive capital throws millions into unemployment and, from there, into “alternative employment” in crime and migration. The destruction of territories includes depopulation. The “phenomenon” of migration is not the prelude to the catastrophe, it is its confirmation. Migration produces the effect of “nations within nations”, large migratory caravans colliding with concrete walls, police, military, criminal, bureaucratic, racial and economic.

When we talk about migration, we forget the other migration that precedes it on the calendar. That of the original populations in their own territories, now converted into merchandise. Have the Palestinian people not become migrants who must be expelled from their own land? Doesn’t the same thing happen with the indigenous peoples of the world?

In Mexico, for example, the native communities are the “strange enemy” that dares to “desecrate” the soil of the system’s farm, located between Bravo and Suchiate. To combat this “enemy” there are thousands of soldiers and police, megaprojects, buying of consciences, repression, disappearances, murders and a veritable factory of guilty people (cf. https://frayba.org.mx/). The murders of brother Samir Flores Soberanes and dozens of nature guardians define the current government project.

The “fear of the other” reaches levels of frank paranoia. Scarcity, poverty, misfortunes and crime are responsible for a system, but now the blame is shifted to the migrant who must be fought until annihilated.

In “politics” alternatives and offers are offered, each one more than false. New cults, nationalisms – new, old or recycled -, the new religion of social networks and its neo prophets: the “influencers”. And war, always war.

The crisis of politics is the crisis of alternatives to chaos. The frenetic succession in the governments of the right, the extreme right, the non-existent center, and what is presumptuously called “left”, is only a reflection of a changing market: if there are new models of cell phones, why not “new ” political options?

Nation-States become customs agents of capital. There are no governments, there is only one Border Patrol with different colors and different flags. The dispute between the “Fat State” and the “Starving State” is just a failed concealment of its original nature: repression.

Capital begins to replace neoliberalism as a theoretical-ideological alibi, with its logical consequence: neo-Malthusianism. That is, the war of annihilation of large populations to achieve the well-being of modern society. War is not an irregularity of the machine, it is the “regular maintenance” that will ensure its operation and duration. The radical reduction in demand to compensate for supply limitations.

It would not be about social Neo-Darwinism (the strong and rich become stronger and richer, and the weak and poor become weaker and poorer), or Eugenics, which was one of the ideological alibis for the Nazi war of extermination of the Jewish town. Or not only. It would be a global campaign to annihilate the majority population in the world: the dispossessed. Dispossess them of life too. If the planet’s resources are not sufficient and there is no spare planet (or it has not been found yet, although they are working on it), then it is necessary to drastically reduce the population. Shrink the planet through depopulation and reorganization, not only of certain territories, but of the entire world. A Nakba for the entire planet.

If the house can no longer be expanded nor is it feasible to add more floors; If the inhabitants of the basement want to go up to the ground floor, raid the cupboard, and, horror!, they do not stop reproducing; if “ecological paradises” or “self-sustaining” (in reality they are just “panic rooms” of capital) are not enough; if those on the first floor want the rooms on the second and so on; In short, if “modern civilization” and its core (private ownership of the means of production, circulation and consumption), is in danger; Well, then you have to expel tenants – starting with those in the basement – until “balance” is achieved.

If the planet is depleted of resources and territories, a kind of “diet” follows to reduce the obesity of the planet. Searching for another planet is having unforeseen difficulties. A space race is foreseeable, but its success is still a very big unknown. Wars, on the other hand, have demonstrated their “effectiveness.”

The conquest of territories brought the exponential growth of the “surplus”, “excluded”, or “expendable”. The wars over the distribution continue. Wars have a double advantage: they revive war production and its subsidiaries, and eliminate those surpluses in an expeditious and irremediable manner.

Nationalisms will not only resurface or have new breath (hence the coming and going of far-right political offers), they are the necessary spiritual basis for wars. “The person responsible for your shortcomings is whoever is next to you. That’s why your team loses.” The logic of the “bars”, “truncheons” and “hooligans” -national, racial, religious, political, ideological, gender-, encouraging medium, large and small wars in size, but with the same objective of purification.

Ergo: capitalism does not expire, it only transforms.

The Nation-State long ago stopped fulfilling its function as a territory-government-population with common characteristics (language, currency, legal system, culture, etc.). The National States are now the military positions of a single army, that of the capital cartel. In the current global crime system, governments are the “place bosses” that maintain control of a territory. The political fight, electoral or not, is to see who is promoted to head of the plaza. The “floor collection” is through taxes and budgets for campaigns and the electoral process. Disorganized crime thus finances its reproduction, although its inability to offer its subjects security and justice is increasingly evident. In modern politics, the heads of national cartels are decided by elections.

A new society does not emerge from this bundle of contradictions. The catastrophe is not followed by the end of the capitalist system, but by a different form of its predatory character. The future of capital is the same as its patriarchal past and presents: exploitation, repression, dispossession and contempt. For every crisis, the system always has a war at hand to solve that crisis. Therefore: it is not possible to outline or build an alternative to collapse beyond our own survival as indigenous communities.

The majority of the population does not see or does not believe the catastrophe is possible. Capital has managed to instill immediatism and denialism in the basic cultural code of those below.

Beyond some native communities, peoples in resistance and some groups and collectives, it is not possible to build an alternative that goes beyond the local minimum.

The prevalence of the notion of the Nation-State in the imaginary below is an obstacle. It keeps struggles separate, isolated, fragmented. The borders that separate them are not only geographical.

-*-

The Contradictions.

Notes:

First series of contradictions:

The fight of the brothers from the Cholulteca region against the Bonafont company, in Puebla, Mexico (2021-2022). Seeing that their springs were drying up, the residents turned to look at the person responsible: the Bonafont company, from Danone. They organized and took over the bottling plant. The springs were recovered and water and life returned to their lands. Nature thus responded to the action of its defenders and confirmed what the farmers said: the company deprecated water. The repressive force that evicted them, after a time, could not hide the reality: the people defended life, and the company and the government defended death. Mother Earth responded to the question like this: if there is a remedy, I correspond with life to those who defend my existence; We can coexist if we respect and care for each other.

The pandemic (2020). The animals recovered their position in some abandoned urban territories, although it was momentary. The water, the air, the flora and fauna had a respite and remade themselves, although they were once again overwhelmed in a short time. They thus indicated who the invader was.

The Journey for Life (2021). In the East, that is, in Europe, there are examples of resistance to destruction and, above all, of building another relationship with Mother Earth. The reports, stories and anecdotes are too many for these notes, but they confirm that the reality there is not only that of xenophobia and the idiocy and petulance of their governments. We hope to find similar efforts in other geographies.

Therefore: balanced coexistence with nature is possible. There must be more examples of this. Note: look for more data, review the Extemporánea reports again upon returning from the Journey for Life – Europe Chapter, what they looked at and what they learned, follow the actions of the CNI and other organizations and movements of sister indigenous peoples in the World. Pay attention to alternatives in urban areas.

Partial conclusion: the contradictions detected put one of the approaches of the complex hypothesis in crisis, but not yet the essence. The so-called “green capitalism” could well absorb or supplant these resistances.

Second series of contradictions:

The existence and persistence of the Sixth and the people, groups, collectives, teams, organizations, movements united in the Declaration for Life. And many more people in many places. There are those who resist and rebel, and try to find themselves. But it is necessary to search. And that is what the Searchers teach us: searching is a necessary, urgent, vital struggle. With everything against them, they cling to the remotest hope.

Partial conclusion: the mere possibility, minimal, tiny, improbable up to a ridiculous percentage, that resistance and rebellion coincide, makes the machine stumble. It is not its destruction, it is true. Not yet. The scarlet witches will be decisive.

The percentage probability of the triumph of life over death is ridiculous, yes. Then there are options: resignation, cynicism, the cult of the immediate (“carpe diem” as vital support).

And yet, there are those who defy walls, borders, rules… and the law of probabilities.

Third series of contradictions: Not necessary. The Excluded Third Rule applies.

General conclusion: therefore, another hypothesis must be raised.

-*-

Ah! Did you think that the initiative or step that the Zapatista people announced was the disappearance of MAREZ and JBG, the inversion of the pyramid and the birth of the GAL?

Well, I’m sorry to ruin your peace of mind. It is not like this. Go back to the so-called “Part One” and the discussion about the motives of wolves and shepherds. Ready? Now put this up:

Permissu et gratia a praelatis dico vobis visiones mirabiles et terribiles quas oculi mei in his terris viderunt. 30 Anno Resistentise, et prima luce diei viderunt imagines et sonos, quod nunquam antea viderant, et tamen litteras meas semper intuebantur. Manus scribit et cor dictat. Erat mane et supra, cicadae et stellae pugnabant pro terra…

With the permission and grace of the superiors I tell you the wonderful and terrible visions that my eyes have seen in these lands. In the 30th year of the Resistance, and with the first light of day, they saw images and sounds that they had never seen before and yet they always looked at my letters. The hand writes and the heart dictates. It was early morning and above, crickets and stars were fighting for the earth…

–-El Capitán.

He did not appear then because they did not know about the death of SupGaleano, nor about the other necessary deaths. But that’s how we Zapatistas roll: what we keep silent about is always more than what we say. As if we are determined to design a puzzle that is always unfinished, always with a pending piece, always with that extemporaneous question: What about you?

From the mountains of the Mexican southeast.

El Capitán.

40, 30, 20, 10, 2, 1 year later.

P.S.- So what’s missing? Well… what’s missing is missing.

Lacking patience, the EZLN’s communique, “Fourteenth Part and Second Approach Alert: The (other) Rule of the Excluded Third Party,” was translated rapidly by the Chiapas Support Committee. You can read the original in Spanish here. And you can also read the Spanish and other translations here too: