Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

THERE WILL BE NO LANDSCAPE AFTER THE BATTLE

(On the Russian army’s invasion of Ukraine.)

ZAPATISTA SIXTH COMMISSION

Mexico

March 2, 2022

To those who signed the Declaration for Life:

To the national and international Sixth:

Compañer@s and herman@s:

We tell you our words and thoughts about what is currently happening in the geography you call Europe:

FIRST – There is an aggressor force, the Russian army. There are big capital interests at stake, on both sides. Those who now suffer from the delusions of some and the cunning economic calculations of others, are the peoples of Russia and Ukraine (and, perhaps soon, those of other geographies near or far). As Zapatistas, we do not support one state or another, but those who fight for life against the system.

During the multinational invasion of Iraq (almost 19 years ago), with the US army at the head, there were mobilizations around the world against that war. No one in their right mind thought that opposing the invasion was siding with Saddam Hussein. Now it’s a similar situation, although not the same. Neither Zelensky nor Putin! Stop the war!

SECOND – Different governments have aligned themselves with one side or the other, doing so by economic calculations. There is no humanistic assessment in them. For these governments and their “ideologues” there are good interventions-invasions-destructions and there are bad ones. The good ones are those made by their likenesses, and the bad ones are perpetrated by their opposites. The applause for Putin’s criminal argument to justify the military invasion of Ukraine will become a lament when, with the same words, the invasion of other peoples, whose processes are not to the liking of big capital, is justified.

They will invade other geographies to save them from “Neo-Nazi tyranny” or to end neighboring “narco-states.” They will then repeat Putin’s same words: “we are going to de-nazify” (or its equivalent) and abound in “reasoning” of “danger to their peoples.” And then, as our comrades in Russia tell us: “Russian bombs, rockets, bullets fly towards Ukrainians and don’t ask them about their political opinions and the language they speak,” but the “nationality” of some and of others will change.

THIRD – Then, when the invasion began, they waited to see if Ukraine would resist, and taking account of what could be extracted from one or another result. As Ukraine resists, then they do begin to issue “aid” invoices that will be collected later. Putin is not the only one surprised by the Ukrainian resistance.

Those who win in this war are the great arms consortia and the big capitals that see the opportunity to conquer, destroy/rebuild territories; in other words, to create new markets of goods and consumers, of people.

FOURTH – Instead of going to what the media and social networks of the respective sides disseminate -and that both present as “news”-, or to the “analysis” in the sudden proliferation of geopolitical experts and sighers for the Warsaw Pact and NATO, we decided to look for and ask those who, like us, are engaged in the struggle for life in Ukraine and Russia.

After several attempts, the Zapatista Sixth Commission managed to make contact with our likenesses in resistance and rebellion in the geographies they call Russia and Ukraine.

FIFTH – In short, these our relatives, who also raise the flag of the @ libertarian, stand firm: in resistance those who are in the Donbas, in Ukraine; and in rebellion those who walk and work the streets and fields of Russia. There are detainees and beaten in Russia for protesting against the war. There are people murdered in Ukraine by the Russian army.

It unites them with each other, and with us, not only the NO to war, but also the repudiation of “aligning” with governments that oppress their people.

In the midst of confusion and chaos on both sides, they are held firm by their convictions: their struggle for freedom, their repudiation of borders and their nation states, and their respective oppressions. that only change flags.

Our duty is to support them to the best of our ability. A word, an image, a tune, a dance, a fist that rises, a hug – even from distant geographies – are also a support that will animate their hearts.

To resist is to persist and to prevail. Let us support these likenesses in their resistance, that is, in their struggle for life. We owe them and we owe it to ourselves.

Above: Subcomandantes Insurgentes Galeano and Moisés

SIXTH – For the above, we call on the national and international Sixth that has not yet done so, in accordance with their calendars, geographies and modes, to demonstrate against the war and in support of the Ukrainians and Russians who fight in their geographies for a world with freedom.

We also call for financial support for the resistance in Ukraine in the accounts that will be indicated to us in due course.

For its part, the EZLN’s Sixth Commission is doing the same, sending some aid to those in Russia and Ukraine who are fighting the war. Contacts have also been initiated with our relatives in SLUMIL K’AJXEMK’OP to create a common economic fund to support those resisting in Ukraine.

Without bending, we shout out and call to shout and demand: Russian Army Out of Ukraine!

-*-

The war must be stopped now! If it is maintained and, as is to be expected, it escalates, then perhaps there will be no one to notice the scenery after the battle.

From the mountains of the Mexican southeast,

Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés SupGaleano

Sixth Committee of the EZLN

March 2022

==Ω==

Originally Published in Spanish by Enlace Zapatista, https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2022/03/03/no-habra-paisaje-despues-de-la-batalla/

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Non-stop “bullet baths” against Tsotsils in Aldama

Above: Cocó community, Aldama, Chiapas – Photo: EFE, Carlos Lopez

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

The daily life of violence can anesthetize public opinion, but not those who suffer it every day. Not one day goes by without bullet baths against more than a dozen Tsotsil communities in the municipality of Aldama, in the Chiapas Highlands. On February 27 alone, La Jornada received the report, in real time, of 31 armed attacks from the community of Santa Martha, in neighboring Chenalhó (municipality). In January 2022 there were 230 attacks. It’s possible that by the end of February they will reach half a thousand.

The alleged reason for this practically unilateral violence (since occasional responses from Aldama are also reported without victims in Santa Martha) is the dispute over 60 hectares (roughly 148 acres) in the lower strip of land between the two indigenous municipalities. From the scale of the aggressions, and the evident and explicit ineffectiveness of government authorities, it is evident that, as Gardel would say, 60 hectares is nothing. That explanation is not enough.

The reports repeat the communities under fire: Cocó’, Xuxch’en, Taba, San Pedro Cotzilnam, Yeton, Ch’ivit, Cabecera, Stzelejpotobtik, Juxton Ch’ayomte’, and sometimes others. Sometimes there are injured or dead. It is remarkable the number of times that the state police, and even the National Guard (NG), are attacked from Santa Martha. Just last February 22, the population of these communities was surrounded by attackers who fired from Yaxaltik, Tulan, Tok’oy Police Base, Saclum, Tojtik, Telesecundaria, T’elemax, T’ul Vitz, Vale’tik, Ontik, Xchuch te’1, 2, K’ante’ Pantheon, Temple, Chalontik, Tijera Caridad, Rancho Caridad, all in Santa Martha, Chenalhó, in addition to El Colado, Chino, Ranchito and El Ladrillo, within the 60 hectares in dispute.

They will make a pronouncement

Without going far, on the 20th, at 12:36 pm, according to the inhabitants of Aldama (they sent photos and videos) “elements of the NG, Navy and state preventive police were attacked in Tabac; the high-caliber shots come from T’elemax in Santa Martha.” In Ch’ivit, the septuagenarian Tomás Lunes Ruiz, who was inside his house, was wounded in the belly at 6:45 in the morning.”

Civil groups and observers in the region that will soon make public a statement to which this reporter had access, emphasize that “the situation of the Tsotsil municipalities of Aldama and Chenalhó is placed within the context of violence that has increased dramatically in various regions (municipalities) of the state: Pantelhó, Oxchuc, Chalchihuitán, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, San Juan Chamula, Simojovel, Altamirano, Ocosingo, Palenque, Chilón, Venustiano Carranza, Tila, Frontera Comalapa, Chicomuselo, Chapultenango, Amatán” and we can add the municipality of Benemérito de las Américas.

The statement adds: “The list of violent episodes, confrontations, murders and disappearances, grows every day throughout the state, as an expression of a clear, accelerated and, apparently, uncontrollable social decomposition. The large number of high-power weapons for the exclusive use of the Army that circulate without any authority intervening is striking. Likewise, the presence of criminal groups, some of national relevance, that operate in absolute impunity is evident.”

It is not, they add, “only intra-community and inter-community agrarian conflicts that in themselves would deserve immediate intervention by the authorities. It’s about a dispute for territorial control, in which interests of all kinds converge, and whose terrible consequences we have seen in other states of the Republic.”

ACTEAL, MEXICO: (Photo credit should read ORIANA ELICABE/AFP via Getty Images)

The open, unpunished and fearsome actions of the paramilitaries of San Pedro Chenalhó, in Santa Martha and other communities, are the direct heir of those who carried out the Acteal massacre in 1997. There are already three generations of armed men, with no other roots than belonging “to the gang”, as visionary Angélica Inda and Andrés Aubry described 30 years ago when studying the situation in Los Chorros and Ejido Puebla, localities that were the cradle, along with Santa Martha, of para-militarism in the region within the government’s counterinsurgency plan, never officially recognized, to counter the influence of the Zapatista Uprising (see Los llamados de la memoria, 2003).

“Faced with this terrible reality” in which no strategy is glimpsed at the three levels of government, observers consulted by La Jornada ask: “Are the authorities overwhelmed? Is there incompetence? Complicity?”

Researcher Carla Zamora Lomelí, with many years of academic work in the Chiapas Highlands documenting the unbridled violence in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, points out: “It’s clear that there is a dispute for territorial control among groups associated with organized crime. The safe houses that shelter hundreds of migrants (as evidenced after the road accident that claimed the lives of 56 people in December) operate in complete impunity, while access to the arms market is simple.” Zamora Lomelí concludes: “In Chiapas the war seems to be perpetuating itself and justice is increasingly diffuse.”

==Ω==

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, March 1, 2022: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/03/01/politica/015n1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

On victories and defeats

Water is Life!

By: Raúl Zibechi

In hegemonic political culture, notions about triumphs and failures, victories and defeats, usually allude to very specific situations, generally linked to the final objectives of the actors in play.

The concept of victory applies to the wide range that goes from electoral triumph to taking power as a result of an uprising or a people’s war, as happened in 1979 in Nicaragua, and before in many other countries. However, on many occasions, victories are celebrated, let’s say tactical or punctual, when certain laws are approved or important difficulties are overcome.

Defeats, on the other hand, enjoy such a bad reputation, that they are rarely assumed by those responsible for them, who, on the contrary, tend to attribute them to external factors outside their control.

The electoral defeat of the Sandinista Front in 1990, to continue with the same example, was so brutal that it paralyzed its actors rather than bringing about a deep reflection on its reasons. The triumph of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 can be read in the same way, which in many analyses is usually attributed to the “betrayal” of then President Boris Yeltsin.

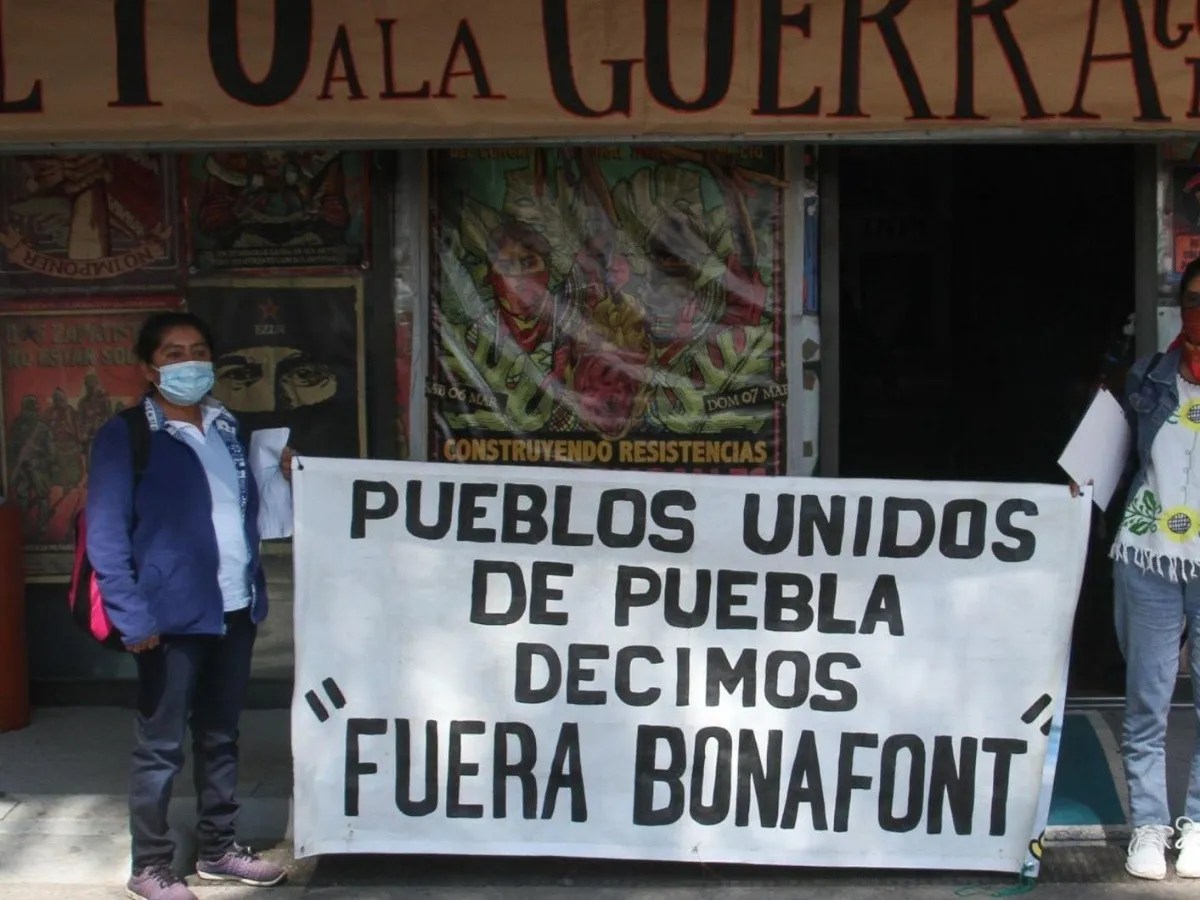

At this moment, it’s not the trajectory of Sandinismo or other victories/defeats that move me to write these lines, but rather something much more recent and, I believe, transcendent: the eviction of the House of the Peoples, Altepelmecalli, in Puebla, by the National Guard and the state police to hand it over to the multinational Bonafont/Danone.

If we are guided by the current political culture, we are facing a clear defeat for the 22 communities and the Pueblos Unidos organization that promoted the plant’s recuperation, and a victory for the federal and state governments. To the contrary, the plant’s closure, on March 22, 2021, International Water Day, should have been considered a victory.

I think that things are completely different. I propose to stop using arguments and concepts that, being adequate for reflecting on inter-state conflicts, or for those whose objective is to occupy the State, are not at all suitable for addressing the resistances of social movements and the peoples in movement.

What would victory be for a native people? And defeat? It’s evident that they are not related to what the system’s politicians and even their followers celebrate, or lament.

The objectives of the peoples have no basic relationship to “external” agendas, whether it be to electoral calendars, revolts to. take power or to bring someone down from power, but rather to what’s most “internal” and profound to a people: their survival as such, the persistence of what makes them continue being peoples. In other words, the difference from the hegemonic culture and modes, or from above.

The great defeat of a people would be its disappearance as a people, the loss of territories, language, ways of life and of relating among its members and with its surroundings. Of course, they need to stop the infrastructure works underway and put limits on looting. But they don’t do it to get greater visibility in the media of above or more negotiating power, but rather because the extractive economy of looting puts them at risk as peoples.

I want to insist that the ways of approaching the resistances of the native peoples, and those below who resist, imply setting aside hegemonic culture (media, bossism, colonial and patriarchal) to comprehend the reasons for and objectives of each action. The great “victory” of the closure of the Bonafont well was that the campesinos’ wells filled up again with water and that that space of death became a space of life for all those who want to stop the dispossession.

Rather than victories or defeats we can talk about steps forward, steps to the side, or setbacks, in the long walk of the peoples about themselves. The resistance of Nahua peoples of the Cholulteca region, has decades in its current phase and centuries if we follow its long-term trail.

Other yardsticks are needed to measure the advances or setbacks of those below: how is the organization, how are the hearts and the state of mind; how many women and girls participate in the activities; do they continue being different because they respect their ways or do they begin to lean on the commercial and open their territories to the logic of capital?

These are some of the aspects that allow them to continue walking, for as long as necessary.

In hegemonic politics, it’s about walking in a more or less straight line towards an objective, sometimes going through enormous sacrifices, to start to rest (so you imagine) when you come to power.

In the logic of the peoples, as Old Antonio already taught us, we walk around and never stop walking, because resisting and struggling is not a “means to,” but rather the way of life chosen to continue being.

==Ω==

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, February 25, 2022: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/02/25/opinion/016a1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Endless Colonialism

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

Outside of some academic debates, a taboo subject in Mexico, and in general the continent, is internal colonialism. Accepting that it exists, the majority societies fear, can undermine the Nation, that sometimes ameboid state that makes us a single country, with defined borders, sovereignty, language and flag. The American nation-states, from Canada to Argentina, inherit the same profound colonization of the European empires, including the Africanization of many regions as a result of slavery imported by the colonizers.

Since the 19th century, the countries of this hemisphere have inherited a progressive dispossession that, with arguments no longer “colonial” but rather “national,” has never been interrupted. It acquires different appearances, and changes with historical conjunctures. In some places it’s a stark and defiant “fait accompli:” the native peoples survive only because they want to, because they don’t deserve territorial or linguistic rights, let alone political rights, unless they are crumbs (particularly in the United States and Brazil).

This situation, which we began to understand from the hand of Franz Fanon barely half a century ago, took a dramatic turn with the non-metaphorical awakening of the native peoples from 1970 forward, accompanied by an unusual demographic upswing. This historical cycle crosses the nations transversally even today, Mexico in first place but also others with a significant native population. It is expressed in demands for autonomy and campesino, government, territorial, linguistic and even ceremonial self-determination.

Indigenous communality clashes with National States, be they progressive or reactionary, neoliberal, dictatorial or revolutionary. Neither the Venezuela of Hugo Chávez, nor the Bolivia of Evo Morales, nor Ecuador with Lucio Gutiérrez and the “rogue” governments stopped colonization on top of these peoples, some very extensive in America (Mayas, Nahuas, Aymaras, Wayuu, Quechuas, Mapuche).

The historical inertia of bottomless invasion and dispossession is such that so far in the 21st century it doesn’t stop or dare to say its name, although international styes and governments are intoxicated with inclusive speeches. Majority societies, even the democratic or progressive ones, take as settled their right to invade in adherence to their laws and for the good of the country.

We witnessed a case of hereditary blindness (with its stretches of light, such as post-revolutionary agrarian distribution or certain aspects of indigenismo and liberation). From Emperor Iturbide to Benito Juárez and his successors until culminating in Porfirio Díaz, the invasion, the dispossession (the extermination if necessary) of indigenous peoples was as natural as invisible. After the PRI-century and what followed, it would take less brutal routes.

The cynical investments of Fox, Calderón and Peña Nieto maintained rhetoric and intentions different from the authoritarian paternalism of López Obrador, but in this case not very different, without sparing consultations, electoral winks, economic lures; nor the force of law. Additionally, there is also an abundance of violence that, as we know, has many arms and denominations: not only legal violence and its repressive powers, there are also paramilitaries that never “exist” for the State (from Acteal in 1997 to Aldama in 2022), criminal gangs, frequent allies of political power, white guards legalized as “security companies” that investors hire to protect the concessions granted by the State.

Mining, water or oil extraction and other “national necessities” have carte blanche with AMLO, as they had in that recent past that he rejects. They want to convince us that the apocalyptic blades of the Spanish and French on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the establishment of an industrial, real estate and railroad corridor that divides the Isthmus doesn’t represent the same thing. Both this big project and the so-called “Maya” Train (tren “maya”) and its Jiménez Pons-type agents, with all their tourist ballyhoo, embody the most recent version of the endless internal colonialism.

The gold may be Canadian, the silver for Slim, Larrea and the late Bailleres, but yes, oil and lithium are for the nation. From the perspective of the native peoples that doesn’t change anything. When, under the theoretical guidance of Arturo Warman, their demands for autonomy were branded a “threat” to national integrity, the government preferred to betray the San Andrés Accords. Today, drug trafficking and the great migration of the poor damage that national integrity more than legalizing indigenous self-determination would have.

This inertia acquires grave environmental, cultural, food, health and co-existence implications. Internal colonialism, always denied, inadvertently opens the doors to a telluric and social disintegration: at this stage of globalization and climate change, it even threatens the integrities it claims to defend.

==Ω==

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, February 21, 2022: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/02/21/opinion/a08a1cul

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Altepelmecalli, the defense of water

Graphic art: @TallerAhuehuete

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

As if it were the work of the devil looking to surface from the depths of hell, an enormous hole opened up in the farmlands of Santa María Zacatepec, Puebla. With an unstoppable appetite, the hole grew day after day. It began on May 29, 2021, with a diameter of 5 meters. In less than a day, it reached 30. Soon after it got to 100 meters. Now it is nearly 130 meters wide and 30 meters deep.

In its voracity, the sinkhole swallowed crops and the house of the Sánchez Xalamiahua family, it cracked the walls of other dwellings and swallowed up puppies Spay and Spike, who were finally rescued. Seen from above, it looked like an enormous moon crater, with openings in the walls that resemble plumbing lines. In fact, the cavity is not isolated. The demon also opened other voids beneath the earth, turning the area into a kind of gruyere cheese.

In La suave patria, (The Gentle Homeland) Ramón López Velarde wrote: The Baby Jesus gave you a stable and the devil, the worship of oil. But in Puebla it wasn’t the exploitation of black gold that the evil one granted, but rather the extraction of blue gold. That was what caused the sinkhole to open. In 1992, the modern Beelzebub gave usufruct rights (the rights to use and enjoyment) of the springs to companies that set up shop in San Mateo Cuanalá, in the municipality of Juan C. Bonilla, Puebla. And, first a bottling plant, and then the transnational Bonafont milked them mindlessly.

Since the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the authorities have extended the guarantee of impunity to big business to do what they want with water resources. A public good such as blue gold has been privatized (https://bit.ly/3s1bLdD). Instead of installing potable water systems, they have facilitated its sale in plastic bottles. Three transnationals control 80 percent of this market in our country: Coca Cola (Ciel), Danone (Bonafont), and PepsiCo (E-Pura) (https://bit.ly/3gXmMqa).

With an insatiable thirst for profits, Bonafont, part of the Danone consortium, extracted one million 640 thousand (1,640,000) liters of water a day, the equivalent consumption of a community of 18,000 inhabitants. Its ambition depleted water tables, left more than 20 communities in the municipality without the vital liquid, and dug an invisible network of tunnels, caverns and subterranean holes which to a large extent, according to a study by specialists from the National Polytechnic Institute, precipitated the appearance of the sinkhole. In exchange, it received 3.28 million pesos daily.

Since 1992, the indigenous Nahuas of the region have opposed the appropriation of water. In order to stop their dissent, the state government imposed an illegitimate mayor on them. Over the years, time and again, they protested against the environmental devastation and the depletion of the artesian wells. In 2008, they blocked the Mexico-Puebla federal highway and symbolically shut down the company. To no avail. The authorities turned a deaf ear to the protest and sided with the transnationals.

Day by day, the situation became increasingly urgent. The wells dried up, water for planting, animals and even human consumption grew scarce. So, on March 22nd of 2021, the International Day of Water, 22 communities, organized in the Pueblos Unidos de la Región Cholulteca y de los Volcanes (United Peoples of the Choluteca and Volcano Region) shut down the plant.

This is what they were doing when the devil appeared in the sinkhole. A religious denomination congregated around the security fence of the hole to pray, to call on mortals to repent their sins, reading biblical quotes and singing biblical songs. Others, more practical, invented a holiday bread by the name of Recuerdo del socavón (Souvenir from the Sinkhole).

Only slightly more than four months later, in the face of governmental negligence, on August 8th, the 142nd anniversary of the birth of General Emiliano Zapata, the indigenous peoples front occupied the plant, plugged the illegal well in which the company stored the water, and founded the Altepelmecalli (House of the Peoples) community center.

The walls of the facilities were adorned with paintings by various visual artists, and all kinds of self-managed projects began to blossom: education, health, raising chickens, pigs and sheep, a community radio station, a library and other activities. Like a miracle, when its savage extraction ceased, the blue gold ceased to be scarce in houses and properties (https://bit.ly/3gXmMqa).

Altepelmecalli became a great center for meetings and gatherings inspired by the environmentalism of the poor. A true crossroads of popular resistance. It adopted as an axis of action the struggle against devastation, dispossession, oppression, exploitation and discrimination. Movements in defense of rivers and water, against open-pit mining, gas pipelines and large hydroelectric plants were given the space to exchange experiences, and refine plans. They honored the memory of community leader, Samir Flores, murdered with impunity in Amilcingo three years ago.

The unprecedented experience of regional indigenous self-organization lasted eleven months. Under cover of darkness, on the morning of February 15th, 2022, the National Guard and state police violently evicted the communities, and returned the facilities to Bonafont.

Far from being an act of justice, the police intervention on behalf of the company is an invitation to open more sinkholes and lower more water tables. The repression against the indigenous Nahuas leaves no question, in conflicts over natural resources between indigenous peoples and large companies, on which side the bread is buttered.

==Ω==

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, February 22, 2022: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/02/22/opinion/016a2pol

English translation: Schools for Chiapas

Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

Post-electoral conflict in Oxchuc, Chiapas

[Admin: Here are 2 articles from La Jornada about the post-electoral conflict in Oxchuc, an indigenous municipality in Chiapas. The town of Oxchuc is located approximately half-way between San Cristóbal and Ocosingo.]

OXCHUC: ONE WOUNDED, HOUSES BURNED IN CHIAPAS CONFLICT

By: Elio Henríquez, February 16, 2022

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas

The conflict that occurred this Tuesday between two groups vying for political power left one wounded by gunshot and six houses burned, among them that of Belisario Méndez Gómez, president of the Community Electoral Body (OEC) of Oxchuc, responsible for organizing the municipal elections by usos y costumbres (uses and customs). [1]

They added that the wounded man, identified as Vicente Méndez Sántiz, allegedly a supporter of the self-proclaimed mayor of Oxchuc, Hugo Gómez Sántiz, was hospitalized at the Hospital of the Cultures, located in San Cristóbal.

The president of the Oxchuc OEC, the only municipality in the state that elects its authorities by usos y costumbres, said in an interview that his house was set on fire on Tuesday at approximately 10 pm by followers of Hugo Gómez. “At 10:00 p.m. neighbors told me that cars full of heavily armed people arrived with cans of gasoline, broke into my house, ransacked it, sprayed gasoline on it and then set it on fire,” he added.

He pointed out that his family managed to leave earlier “because there had already been threats and they detonated high caliber firearms near the house,” which is located in the municipal seat. “My house is one-story, with some little wooden cabins on top, they destroyed it. Those who entered are led by Hugo Gómez Sántiz, self-proclaimed municipal president, and the same people as always did it. Those who directed the burning are Oscar Méndez Sántiz, Javier Sántiz Gómez, Sergio López Méndez and Javier Gómez Méndez.”

Méndez Gómez assured that: “I am not a politician. I am serving my people. In March 2021, I was elected by the assembly of 133 communities and 25 neighborhoods. I am providing a service. I entered to serve and I did not imagine that this would happen.” He commented that before December 15, when the plebiscite was held to elect the new authorities, “there were already death threats against me and my family, from Hugo Gómez’s armed group.”

He said that the house they burned is the only one he has, so he could not take out his belongings; “they stripped me of all my property”, and he said that “Hugo has kidnapped the municipality with a heavily armed group. All this is the work of him who wants to be president by means of violence and firearms.”

The sources consulted reported that the other houses set on fire are owned by followers of Hugo Gómez.

In the inconclusive December 15 municipal elections by raised hands, the OEC of Oxchuc declared Enrique Gómez the winner, a result that was ignored by Hugo Gómez, whose followers unleashed violence before the end of the meeting and took possession of the mayor’s office.

On December 31, the local Congress appointed a municipal council, presided over by Roberto Sántiz Gómez, who works in an office located in San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

The Electoral Tribunal of the State of Chiapas ruled last week that new elections must be held by a show of hands “in a framework of civility, respect, certainty and legality, based on their uses and customs,” and that the legislature must appoint a new municipal council, since the current one did not comply with all the legal requirements.

[1] Usos y costumbres (uses and customs) refers to indigenous customary law in Latin America, and to the various forms of self-governance practiced by different peoples.

==Second article ==

FOLLOWERS of the SELF-PROCLAIMED MAYOR of OXCHUC ATTACK OPPONENTS

By: Elio Henríquez, February 16, 2022

San Cristóbal De La Casas, Chiapas

Followers of the self-proclaimed mayor of Oxchuc, Hugo Gómez Sántiz, fired shots outside a school in the urban zone, at the end of a community assembly yesterday afternoon in which some 200 people participated.

There were no injuries, but some people leaving the school were beaten, the president of the Community Front for the Defense of the People’s Self-Determination, Óscar Gómez López reported.

Meanwhile, unofficial sources indicated that both groups exchanged gunfire and at least four houses were set on fire.

Gómez López pointed out that more than 100 people attending the event locked themselves in one of the classrooms of the Tierra y Libertad elementary school and threw themselves on the floor because the aggressors began to shoot “at a distance of 500 or 800 meters.” At press time they were still taking cover.

He stated that the meeting between authorities and community representatives began around 10 o’clock in the morning in order to reach agreements on the ruling of the State Electoral Tribunal of the State of Chiapas (Teech) which last week ordered the election in this municipality to be repeated, because the one called on December 15 did not conclude.

On that occasion, the community electoral body of Oxchuc, the only locality in the municipality that elects its authorities by usos y costumbres, declared Enrique Gómez López as the winner, a result that was ignored by Hugo Gómez, whose followers unleashed violence and took over the mayor’s office.

On December 31, the local Congress appointed a municipal council presided over by Roberto Sántiz Gómez, who is based in San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

Once yesterday’s meeting was over, those present were about to leave “when they began to shoot at them and thank God none of them were shot, but they began to hit several of them. They took them to the international highway; but the townspeople arrived to rescue them, and at the end came the shooting with high caliber bullets,” explained Óscar Gómez.

“The tired people began to respond because we are there in our houses in town, and we had to defend ourselves with stones because they were aiming shots at the school,” he added.

He stated that when the community leaders were on their way to the assembly in the morning, some of them were beaten at the blockades set up by followers of Gómez Sántiz, in addition to “having their backpacks taken away,” but they managed to get there.

He asserted that in yesterday’s meeting it was agreed to ratify Enrique Gómez as municipal president. “We have the majority and we are not going to accept the imposition of the government.”

The Teech ordered new elections to be held by show of hands “in a setting of civility, respect, certainty and legality,” and that the legislature appoint a new council.

==Ω==

Translations: Schools for Chiapas

Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

Stop the Repression of the Indigenous Peoples of Mexico!

To the Mexican people:

To the peoples of the world:

To the Sixth in Mexico and abroad:

To the media:

We denounce that on February 15 at approximately 1:20hrs, the repressive agents of the bad government including the National Guard, the state police of Puebla and the municipal police of Juan C. Bonilla, invaded and dismantled the space of resistance and organization of the Altepelmecalli House of the Peoples, an autonomous political and cultural space that until March 22, 2021 was a factory owned by Bonafont. Bonafont is a transnational corporation that has for years stolen and hyper-exploited the aquifers in the Cholulteca region.

We fervently condemn the heightened repression by the capitalist government, which calls itself the “4T,” [i] of the resistance and struggle for life waged by our brothers from the United Peoples of the Cholulteca and Volcanos Region [Pueblos Unidos de la Región Cholulteca y de los Volcanes], who converted that landscape of death into a space of encounter and exchange despite determined efforts to impose the Integral Project for Morelos in the states of Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala[ii]. That megaproject would put a natural gas pipeline through the territories of the peoples of the volcano, where old and new forms of organization are sprouting seeds of hope and rebellion.

We are on high alert given the possible persecution of our brothers and sisters from the Altepelmecalli House of the Peoples. We hold the Federal Government responsible for using its armed National Guard thugs to intensify the war of money against life. We hold the government responsible for protecting the Bonafont company, which displaces, steals, privatizes and immorally profits off our people’s waters, creating harm in the form of sinkholes and the running dry of wells, springs, rivers and gullies. This is what has happened to the Metlapanapa river, which the People’s Front of the Cholulteca and Volcano Region [Frente de Pueblos de la Región Cholulteca y los Volcanes] has defended against the river’s exploitation and pollution by industry.

We denounce this repressive offensive on the part of Mexico’s neoliberal bad government against our compañeros and compañeras who are raising the flag of organization from below in their geographies and convoking us to struggle for life. We condemn the following:

- The assassination of our compañero, Francisco Vázquez, president of the ASURCO Monitoring Counsel[iii], who raised his voice against the theft of water from the ejidos of the Ayala region as part of the operations of the thermoelectric plant in Huexca, Morelos.

- The criminalization of the Otomí people, and of our compañero Diego García by the head of that shadowy institution of the bad government called INPI [National Institute for Indigenous Peoples], which has served to extend the indigenist and clientelist control of our peoples, and whose offices used to be located in what is today the Samir Flores Soberanes People’s House.[iv]

- The persecution of the Indigenous Supreme Council of Michoacán for their recent mobilizations against disrespect, racism, and dispossession and for the removal of the appalling monument known as Los Constructores (The Builders) in Morelia, Michoacán[v].

- The indifference and criminal complicity of the National Guard in the face of violence in Guerrero where drug cartels attack the communities of the Indigenous and Popular Council of Guerrero- Emiliano Zapata who oppose the extractive megaprojects and denounce the governments’ complicity with narco-paramilitary groups that kill and disappear our brothers[vi].

- The militarization of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in order to impose the Salina Cruz-Coatzacoalcos Interoceanic Corridor megaproject[vii] as well as the illegal occupation of our communities’ lands for this project like what’s happening in the Binnizá community in Puente Madera[viii] belonging to the commons of San Blas Atempa, Oaxaca.

- The utilization of the National Guard and armed state and municipal groups to stifle the demands of normalistas [ix] students in Ayotzinapa, Tiripetío and Mactumatzá for justice[x] and for recognition of their terms for the escuelas normales.

We hold the Mexican federal government responsible for the escalation of repression against our peoples, and we demand that the National Guard and police forces cease actions against those who oppose the exploitation and destruction of nature and the plundering of the territories and community heritage of original peoples in order to impose megaprojects of death promoted by the Mexican State.

We call on the peoples, nations, and indigenous tribes of Mexico, as well as on allied organizations and collectives, to be on alert for this wave of neoliberal repression announced by the capitalist government of this country in an agreement published in the Official Journal of the Federation on November 22, 2021.[xi] This agreement also declares the projects and federal governmental works matters of public interest and national security which they can then use as a pretext to exercise armed force against peoples who oppose this unprecedented dispossession and destruction of Mexican territory.

We call on the people, groups, collectives, organizations, and movements in the territory of SLUMIL K´AJXEMK´OP (also known as “Europe”) to mobilize and come out against the transnational corporation Bonafont-Danone, headquartered in France, and the agencies of the current Mexican federal government in Europe.

For life! Solidarity and support for the original peoples of the National Indigenous Congress!

Sincerely,

February 16, 2022

For the Full Reconstitution of our Peoples Never Again a Mexico Without Us

National Indigenous Congress—Indigenous Governing Council

Zapatista National Liberation Army Sixth Commission.

[i]The López Obrador campaign has deemed its governing project the “Fourth Transformation” (4T), supposedly on par with historic events such as Mexican Independence (1810), a period of reform in the mid-19th century, and the Mexican Revolution (1910).

[ii] “The Integral Project for Morelos, for example, consists of two thermoelectric plants and well as gas and water pipelines that will dispossess the Nahua indigenous peoples who inhabit the Popocatépetl Volcano region in the states of Morelos, Puebla, and Tlaxcala of their land, water, security, health, identity, and life on the land. The State, along with Elecnor, Enagas, Abengoa, Bonatti, CFE, Nissan, Burlington, Saint Gobain, Continental, Bridgestone and many other companies have imposed this project via the use of state, federal, and military violence, instilling terror in the inhabitants through torture, threats, imprisonment, judicial persecution, the closing of community radios, and now the murder of our brother Samir Flores Soberanes.” https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2019/03/12/samir-lives-the-struggle-continues-declaration-from-the-third-national-assembly-of-the-national-indigenous-congress-the-indigenous-governing-council-and-the-ezln/

[iii] Francisco Vázquez was assassinated on February 11, 2022 in Ayala. ASURCO is the Asociación de Usuarios del Río Cuautla [Cuautla River Users’ Association].

[iv] The Otomí community in Mexico City has occupied the INPI offices in Coyoacán since October 12, 2020, renaming it the Samir Flores Soberanes People’s House at the anniversary of the occupation in October 2021. https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2021/10/06/cdmx-invitacion-a-celebrar-con-resistencia-y-rebeldia-un-ano-de-la-toma-del-inpi/

[v]On February 14, 2022 the Indigenous Supreme Council of Michoacán tore down the statue known as “The Builders” [Los Constructores] that depicted the Spanish priest Fray Antonio de San Miguel giving orders to a group of enslaved indigenous people, symbolizing domination and genocide of the indigenous by the Spanish.

[vi] Most recently, on January 30, 2022, the Indigenous and Popular Council of Guerrero-Emiliano Zapata was attacked by the narco-paramilitary organization called Las Ardillas (The Squirrels). The attack lasted for two hours during which the governmental authorities never responded or intervened.

[vii] The Salina Cruz-Coatzacoalcos Interoceanic Corridor is one of the largest proposed megaprojects that would connect the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean by a rail line between two ports in the states of Oaxaca and Veracruz.

[viii] On February 4, 2022, two people were caught deforesting and fencing off areas of Pitaya communal lands without the community’s permission.

[ix] Normalista refers to students that participate in the Escuelas Normales which are teaching colleges that principally train rural and indigenous young people to be teachers in their own communities.

[x] In 2014, 43 students from the Escuela Normal in Ayotzinapa in Guerrero were abducted and disappeared.

[xi]The announcement is posted here in Spanish: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5635985&fecha=22/11/2021

Puebla police and the National Guard reclaim Bonafont plant

Workers clean the Bonafont water plant, reclaimed yesterday morning by members of the Puebla police, with the support of the National Guard, after evicting members of the Union of Peoples of Cholula who had renamed that space as the House of the Peoples Photo: Cuartoscuro

Nahuas accuse the authorities of putting transnational interests first

By: Yadira Llaven | La Jornada del Oriente

Puebla, Puebla

At dawn on Tuesday, members of the National Guard and state police evicted the inhabitants who since March 22, 2021 occupied the bottling plant of the French firm Bonafont, located in the community of Santa María Zacatepec, municipality of Juan C. Bonilla, 20 kilometers from the capital of Puebla, which they blame for the scarcity of water in the region due to extracting more than a million cubic meters of the liquid in excess of what is allowed.

In the afternoon, the 20 Nahua peoples of the Cholulteca regions and the Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatépetl volcanoes held a virtual press conference in which they blamed President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the governor of Puebla, Luis Miguel Barbosa Huerta, and the municipal president of Juan C. Bonilla, José Cinto Bernal, for coordinating to defend Bonafont, that for 30 years has overexploited the water in the area of the volcanoes.

Barbosa Huerta, of Morena, distanced himself from the operation. He explained that the public force complied with an order of the Judicial Power of the Federation and called on the company and the peoples to dialogue.

A spokesman for the opponents explained: “They forcibly entered the facilities, dismantled the house that had been installed since March 2021, when the bottling plant was closed by decision of the assembly of the peoples of the region to stop the looting of water. They ignored and violated our self-determination.”

They dismantled the House of the Peoples and erased murals

Those in uniform, he added, erased the murals that various artists painted to support the construction of the House of the Peoples and that gave identity to the space. There were no arrests or injuries.

In the morning, the troops handed over the facilities to their owners; Company personnel surrounded the plant’s entrance with cyclonic mesh fencing, dismantled the opposition camp, loaded their belongings into a farm truck and took them away.

In a statement, the group United Peoples of the Cholulteca Region (Pueblos Unidos de la Región Cholulteca) said: “With the excessive presence of public forces from the three levels of government, once again they dispossess and repress the peoples that closed the Bonafont bottling plant of the Danone corporation for almost a year.”

In a press conference, opponents accused the three levels of government of violating the self-determination of the original communities with the entry of public force into the House of the Peoples, bastion of the organization of United Peoples of the Cholulteca Region and of the organizations that have coordinated the resistance in defense of water at the national and international levels.

“They are guilty of perpetrating the environmental disaster that the Bonafont company, of the Danone corporation, has caused for almost 30 years in the communities surrounding the Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl volcanoes; they, the businessmen and the State, believe that kidnapping the facilities of the Altepelmecalli (House of the Peoples in Nahua) will defeat us, but we are not going to retreat, we will defend water and life,” the activists warned.

From Juan C. Bonilla, they warned that they will recuperate what belongs to the peoples, “as we have done historically, and we will enforce the law of our communities. Bonafont out! Danone out! Stop the repression of the peoples who defend life!” they exclaimed.

The Bonafont plant was occupied on March 22, 2021, during the commemoration of World Water Day, in protest of the fact that overexploitation has dried up rivers, wells and springs in the region.

In the media conference he offers every morning, the governor called on the company and the people to dialogue with the participation of the federal and state governments. He said that respect for human rights must be guaranteed and announced that he will protect the region’s water.

They announce a global boycott and ask for support from the EZLN

In recent months this conflict has gained relevance in Latin America. The protest against Bonafont reached the headquarters of the Danone Group in France, and collectives from Europe, the United States and Canada showed solidarity in the struggle for the defense of water in Juan C. Bonilla.

In social networks, communities that support the inhabitants declared themselves in permanent assembly and “maximum alert” before the possible reactivation of the bottler. “We started a permanent campaign of mobilization, boycott and sabotage against the Bonafont company on a global scale.”

Solidarity from Raúl Zibechi

The organization requested the help of the Zapatista National Liberation Army, the National Indigenous Congress and the Indigenous Government Council to stop the repression and demand the return of what they call the Altepelmecalli Cultural Center.

In Mexico, they said, there is an escalation of violence against organized peoples. Just this week, they recalled, there was repression on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and against the normalistas of Ayotzinapa (Guerrero) and Mactumatzá (Chiapas); In addition, Francisco Vázquez, a water defender in Morelos, was murdered for opposing the thermoelectric plant in Huexca. They argued that these are signs that “we are living a world war for water against peoples and humanity.”

Uruguayan journalist and researcher Raúl Zibechi released a video message in which he expressed his solidarity with the inhabitants who occupied the Bonafont plant and called for vigilance at the outcome of these events.

“From here I want to show solidarity with the comrades of the House of the Peoples, who until a few hours ago were occupying the Bonafont company in Puebla and were evicted in a massive, violent operation by the National Guard and police of the state of Puebla.

“The struggle continues, the struggle continues. The House of The Peoples is not to be lost; it is a space that has been very important in these months, in the resistance of the Nahua peoples of the valley where they are, there in Puebla, and a reference point of the resistance to mega-mining, mega-projects and wind farms throughout Mexico, so that throughout the world we must redouble solidarity with the House of Peoples,” insisted the also collaborator of La Jornada.

With information from Fernando Camacho Servín

==Ω==

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Wednesday, February 16, 2022: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/02/16/estados/024n1est

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The Altepelmecalli in Puebla: from a Bonafont plant to a symbol of Resistance

The peoples’ struggle to stop the extraction of water will complete one year

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

Cuanalá, Puebla

Resistance is breathed when one reaches it. A bottling plant used to operate on this central property in the semi-rural municipality of Juan C. Bonilla, near the city of Puebla. About those industrial facilities that one sees when driving on the roads and seem to be a “normal” part of the landscape. After being one more plant of the transnational Bonafont, it became the Altepelmecalli, a cultural center dedicated “to the care and defense of the territories for life.”

Next to the ideogram of the Nahua name of the facilities recuperated by the residents, one can read: “Here the people rule.” Challenging as it sounds, it is, for now, true. And the transformation could not be more eloquent.

The company’s daily extraction reached one million 600 thousand liters per day, equivalent to the total consumption in a municipality of 18 thousand inhabitants.

Currently, the illegal well where the company used to store the liquid inside the facilities was covered by the women and serves as a chicken coop under a sign: “death pit.”

In the same way, what was the re-labelling area is now used to raise sheep and the oil warehouse has become a pigsty.

On March 22, 2021, indigenous people closed the plant to commemorate International Water Day. The surrounding towns, relates El Campeche, one of the movement’s spokespersons, “were running out of water.” Then, “we organized 22 communities and gathered 6 thousand signatures against the company”. They became known as United Peoples of the Cholulteca Region and of the Volcanoes.

They attributed the hollowness to extraction of the liquid

The movement, part of the resistance of the Peoples’ Front in Defense of Water and Land of Morelos, Tlaxcala and Puebla, gained visibility due to the unfortunate appearance of a large sinkhole in Zacatepec, within the same municipality.

The sinking of land was attributed to the indiscriminate extraction of water. Today, a typical local product is “pan de socavón” (sinkhole bread).

Last August 8, given the negligence of the National Water Commission (Conagua), the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples and the Puebla government to stop the looting of water, the peoples peacefully occupied the plant and transformed it into the “house of the people” and a place to meet with similar movements and struggles in the country.

From January 27 to 30, the “International course-workshop for the defense and care of the territories of life: community mapping and social cartographies” was held here.

On the 17th, the National Meeting against gas pipelines and death projects concluded right here, where more than 15 struggles from all over the country denounced that: “the presidential decree of November 22, 2021 represents a new attack against those who defend life because, despite the fact that megaprojects have been imposed without the consent of our peoples and through force, today dispossession and imposition are legalized, attempting to nullify the possibility of organizational action and legal action against those of us who defend life and our territories, by declaring the los megaprojects of public interest, national security, outside all environmental protection and the right to self-determination of our peoples.”

While the state government has failed to intervene directly, Conagua and other federal agencies have also failed to resolve indigenous demands.

One possible route for solution is expropriation of the property, but the risk is that the municipal government, headed by PAN member José Cinto Bernal, with a history of repression in Zacatepec, diversion of resources, creation of an illegal “police” and responsible for various forms of violence will capitalize on it. That would stop the action of the Altepelmecalli and would not resolve the historical injustice.

The bottler arrived in 1992

The bottler arrived in 1992, with the support of Governor Manuel Bartlett Díaz, who imposed, says El Campeche, an illegitimate municipal government to avoid indigenous opposition. Later, Bonafont acquired the company. It doesn’t seem viable for it to return, the disrepute of its actions in the region doesn’t favor it, although the defenders of the Metlapanapa River, a tributary of the highly polluted Atoyac, have been pursued legally.

To commemorate the first anniversary of the closing, the organizations in defense of territory and water in the country that struggle against hydroelectric dams, gas pipelines and the extraction of water and minerals, announced a Peoples’ Caravan for Life and Against Megaprojects, from March 22 to April 22, which will leave from this Altepelmecalli.

==Ω==

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, February 1, 2022

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/02/01/politica/013n1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee