Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

The word “common” is not just any word: 32 years after the Zapatista uprising.

By Andrea Cegna | Desinformémonos | January 2, 2026

“The word ‘common’ is not just anything,” declares Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés from the stage in Oventic, Caracol II, during his speech commemorating the thirty-second anniversary of the start of the Zapatista revolution. The EZLN leader adds: “It is much more difficult and much greater than that of ’94. Because it means uprooting the capitalist system. It means removing from our minds what they have forced upon us.” And he immediately clarifies the scope of this break: “We don’t want to be owners. I’m not just talking about the land, but about everything. We no longer want ‘mine’ or ‘I.’ What we mean by ‘the common,’ perhaps some will say it’s madness. Yes, we can accept that: madness. But for everyone, not just for a few.”

In the mist that since morning has enveloped one of the best-known headquarters—also due to its proximity to San Cristóbal de Las Casas—of neo-Zapatismo, the central event of the celebrations opens a spatial-temporal crack. When the EZLN General Command takes the stage, the mist lifts, the music stops, and in the distance, the sound of the militia’s staffs can be heard, which, as part of the opening, burst forth in front of the stage, marking the rhythm of the night.

The EZLN is an army that wants to build peace, is tired of war, wants life and not death, and precisely for this reason it is anti-capitalist: capitalism as a systemic element of the destruction of life, in all its forms, in the name of the obsession of accumulating wealth. Moisés says it without mincing words: “That is why we say and confirm that we will continue in our political, ideological, and peaceful struggle. Because we do not want death. We want life. But we want a life that we decide for ourselves, not one decided by those above us.”

And he adds: “We will always be peaceful. And if they don’t allow us to be, we will defend ourselves as our fallen comrades taught us thirty-two years ago. We are like them. And like them, we are ready and willing.” “We have a great responsibility, comrades. And we are going to do it because there is no other option.”

An intense, emotional, and lengthy speech, which shows the growth of Moisés, called upon about a decade ago to take the place of one of the most iconic revolutionary figures of the modern world: Marcos. A courageous decision by the EZLN, which revealed a distinct and complex nature, deeply rooted in the worldview of the indigenous peoples, but not solely in that.

Constructing a new relationship with life

Marcos has not disappeared and has reappeared these days at CIDECI in San Cristóbal, intervening on several occasions in the “seedbed,” which in Italian could be translated as a word related to the world of agriculture and not to debates and seminars, and which in the Zapatista conception is a space for training that sows seeds to harvest anti-capitalism. Marcos spoke again in the form of a narrative, a choice made years ago to be able to communicate with the indigenous communities and make the analyses of the revolutionary vanguard—which on November 17, 1983, gave life to the first camp—understandable and replicable.

In addition to the narrative read on December 29, Marcos added twelve points. “The crucial question is: is it possible to construct a geography and a calendar, a spatial-temporal eruption, in which another logic of production and relationship with nature allows—mind you: allows, not necessarily creates—a new form of relationships between living beings, considering nature as the whole of which humanity is only a part?” he says in the seventh point.

In the last point, he returns to the war: “The ‘failures’ and ‘dysfunctions’ of the system are not failures or dysfunctions: they are an essential part of a war machine that advances by conquering through destruction and annihilation, only to then rebuild and reorder social relations. Social programs like Sembrando Vida and its “welfare” equivalents do not fail or are incomplete: they fulfill their function and role in the war of conquest. With historical myths, recommendations, and advice to young people, the elders urge them to face the storm with a toothpick and demand that they be grateful for life. It’s actually a small stick, but I think you understand it as a toothpick. In the Zapatista communities, facing the present and thinking about the future, they return to their own history.”

The EZLN, today, proclaims and practices a political space where property and the pyramid are set aside, not to be replaced by new elites

But looking at the EZLN solely through the lens of its political and theoretical leadership is a mistake that has been repeated time and again. Because what Zapatismo truly calls into question is not only capitalism as an economic system, but the pyramid of power that makes it possible: the idea that someone must be at the top and someone at the bottom, that command is concentrated and life is reduced to obedience. The pyramid is the symbol of this world order, just as private property is its material foundation.

The Oventic fog lifts around 11 p.m., just as the EZLN Command takes the stage and neo-Zapatista militia members occupy the center of the basketball court at Caracol II. Earlier, for hours, theatrical performances and marimba music filled the afternoon; the communal dining hall provided food; in another corner of the Caracol, beef broth was distributed free of charge. This is not mere decoration: it is concrete politics. Collective organization, care, daily life that functions without a market and without vertical command.

Building autonomy from below

The Common, as Moisés affirms, is the radical questioning of both foundations of capitalism: property and the pyramid. Questioning property means breaking with the idea that land, labor, time, and life can be appropriated. Questioning the pyramid means rejecting the accumulation of power and its separation from the communities. The EZLN, today, proclaims and practices a political space where property and the pyramid are set aside, not to be replaced by new elites.

It’s not about rhetoric, but about daily organization. The strength of the EZLN lies in its ability to build autonomy from below: in community assemblies, in the Caracoles as spaces of coordination and not command, in the rotation of responsibilities, in the collective control of decisions. It is there that the pyramid is emptied, because it finds no place to take root. It is there that politics ceases to be representation and becomes shared practice once again.

Zapatismo is no longer fashionable today. It is outside the mainstream media, outside the constant narrative, and there are those who lose their bearings or file it away as a myth of the 1990s. But precisely away from the spotlight, it continues to resist: forced migration, the advance of organized crime, militarization, the reassuring narrative of the central government and the media that speak of development and pacification while dispossession and violence advance in the territory. The EZLN survives not because it has become an icon, but because it is a living political process, capable of reorganizing itself and resisting the passage of time without abandoning its principles. In this sense, Zapatismo is neither a nostalgic memory nor a closed chapter: it is a revolution that does not seek to seize power, but to dismantle it. And precisely for this reason, it remains unsettling. And necessary.

_________________________________________________

Read the original in Spanish here at Desinformémonos. Snap translation by Chiapas Support Committee.

Interview with Raúl Romero: 42 years of the EZLN, “one of the hearts of the anti-capitalist movement”

Interview: A sociologist and activist closely linked to the Zapatista movement through academia, journalism, and activism, Raúl Romero reflects on the current strength and relevance of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), which, fueled by new practices related to the commons and non-ownership, is celebrated its 42nd anniversary in November 2025.

Written by: Sergio Arboleya at Zur

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) recently celebrated 42 years of existence, founded on November 17, 1983, when a group established a camp in the Lacandón rainforest to begin the first stage of organizing the movement with indigenous communities of Chiapas.

This silent network burst onto the global stage just over a decade later when it rose in arms on January 1, 1994, to demonstrate its radical opposition to the start of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), signed by Canada, the United States, and Mexico, then governed by Carlos Salinas de Gortari, a political emblem of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

Since then, the EZLN has shaken the global political scene by proposing an ideology that, contrary to the long tradition of Latin American guerrilla organizations, did not aim to seize control of the state apparatus but – in the words of the intellectual John Holloway, who masterfully defined it in a resounding phrase – “to change the world without taking power.”

Three decades ago, in a continent dominated by neoliberal administrations, the emergence of Zapatismo represented an innovation capable of outlining a new horizon for the collective social imagination, spreading its ideology and methods while always emphasizing that in specific territories, it was the local communities that should lead their processes, “each in their own way.”

The magnetic figure of Insurgent Subcomandante Marcos (now a Captain, in another unique demonstration that here the leaders “descend” instead of continuing to rise in the structure), with his remarkable literary skills, broadened the subjective base of the movement and facilitated its penetration, transcending physical and ideological borders.

However, Zapatismo was not merely an aesthetic movement; it involved far more daring and extreme political stances, such as generating “The Other Campaign,” capable of circumventing electoral logic and running counter to the approach adopted by the wave of self-proclaimed progressive governments that reshaped the map of Latin America 10 years after that Chiapas uprising. Although it never remained static, since that moment in the regional calendar, the EZLN and its base have gone through different phases that, broadly speaking, could be described as a certain withdrawal from the international stage and a profound retreat into the indigenous communities. During this period, they strengthened the National Indigenous Congress (CNI, which they had fostered since 1996), with which they attempted to participate in the 2018 presidential elections, supporting the candidacy of the Nahua woman Marichuy. In those elections, Manuel López Obrador ultimately prevailed, becoming the first center-left president (with all the caveats that might be added) in the country’s history.

This kind of withdrawal from international political discourse did not prevent the creation of the Zapatista Little School (2013) nor, a couple of years later, the announcement of “The Storm,” another metaphorical figure used to explain, with sharp precision and without euphemisms, the scope of the new global era. In the same vein, they called for the exercise of critical thinking in the face of the capitalist hydra and also for the formation of “seedbeds” capable of gathering autonomous experiences in different regions of the world.

The pandemic context and the siege by paramilitary groups led to greater isolation, which was reversed externally when, at the end of 2021, the Journey for Life was launched. This included a trip on the ship La Montaña as part of a larger delegation bound for Europe, with future stops planned for other continents. Since last December, this has been followed by the International Meetings of Rebellions and Resistances, where the focus was both on moving towards “the day after” and on conducting a public self-criticism of the political organizational model. This led to the creation of a new model, which Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés summarized as dismantling the pyramidal structure of the Good Government Councils and the Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities. These bodies are to be replaced by Local Autonomous Governments, the Collective of Zapatista Autonomous Governments, and the Assembly of Collectives of Zapatista Autonomous Governments in the 12 regions that make up this territory.

Sociologist Raúl Romero, who participated in one of the panels held during these meetings between the end of 2024 and January 2nd of this year, highlights these aspects of Zapatismo’s approach to “understanding the dynamic nature of the constant change taking place in the communities, structural changes that occur based on their control of the territories.”

“Zapatismo today, at a global level, is one of the hearts of the anti-capitalist movement at a time when the world has shifted significantly to the right and is experiencing what some would describe as a civilizational crisis.”

In a conversation with Zur from Mexico City, the intellectual and activist quotes Rosa Luxemburg and emphasizes that “in Zapatismo there are three main characteristics that coincide greatly with what happened in the Paris Commune: First, there is the destruction of the state apparatus to create a form of popular self-government based on assembly-based decision-making and their own governmental structures. Second, there is a destruction of the state’s repressive apparatus and, in its place, a popular army with its community authorities built by this autonomous government of the communities. And third, and perhaps most importantly, the recovery of the territories as means of production that allow for the material and cultural reproduction of life, which is what sustains everything else.”

Raúl Romero, an academic technician at the Institute for Social Research and a professor at the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, is a frequent columnist for the Mexican newspaper La Jornada, co-coordinator of the book “Local Resistances, Global Utopias” (2015). He is responsible for the recently launched “Thinking Together About Alternatives,” among other professional activities; Romero emphasizes that Zapatismo, “from its consolidated territory and its armed organizational structure, engages in dialogue with the indigenous peoples of Mexico and the world.”

Drawing on his knowledge and commitment as part of several collectives of adherents and sympathizers of the autonomous ideas that have emerged from Chiapas, he believes that “Zapatismo today, at a global level, is one of the hearts of the anti-capitalist movement at a time when the world has shifted significantly to the right and is experiencing what some would describe as a civilizational crisis.”

And elaborating on this scenario, he points out: “Precisely in the face of this crisis of the liberal management of capitalism, which claimed certain ideas that were lies but were accepted as truth, such as liberal democracy, human rights, and discourses about progress and science, while particularly in Latin America, progressive movements failed to deliver for the popular sectors, the fascist approach emerges, which is completely retrograde, anti-rights, and even operates with a logic of eliminating populations and applying models of accumulation by dispossession, extractivism, the degradation of territories, and confrontation with indigenous peoples. Therefore, in this situation of wars, climate crisis, and the rise of the right wing, Zapatismo is positioning itself as an anti-capitalist left-wing reference point that allows it to offer not only a discourse, a practice, and a theory, but also a conceptualization of the world.” To elaborate on this point within the context of a conversation whose fragments were broadcast on the program Después de la deriva (After the Drift) in Buenos Aires, Raúl resorts to a powerful metaphor that seems to draw from the rich metaphorical tradition inherent in the EZLN itself, asserting: “While Zapatismo has always been committed to viewing and building its work from the autonomy of its territories, it has never stopped dreaming of a vision as vast as the world, and therefore I believe it is not a localist or nationalist movement, but an internationalist one.”

How much do you think the concept of non-ownership impacts the Zapatista movement’s international positioning?

I consider it one of the boldest and most innovative proposals because it stems from understanding the recovered territories as territories that can be shared with other non-Zapatista communities, even those who were previously opposed to them, so that they can work the land together. This idea has also led to other initiatives, such as the construction of a hospital operating room currently underway in Zapatista territory, in which both Zapatista and non-Zapatista communities are participating. This redefines the idea of radicalism, which the Zapatistas say they arrived at after consulting with their elders and ancestors, asking them how they had survived exploitation, contempt, and domination by local bosses and landowners in the past. They responded that they found common ground when they escaped the plantations and went to live in the mountains and the jungle.

Can this position be interpreted as a response to the practices of progressive governments that promoted individual land ownership?

In Mexico, we currently have a government that could be classified as progressive, a very watered-down, second-generation progressivism that lacks the same impetus and radicalism as others, such as those of (Hugo) Chávez and Evo (Morales). The Mexican government under Claudia Sheinbaum, in addition to having a framework of extractivist megaprojects and militarization, launched the “Sembrando Vida” program, which they present as the Mexican version of “good living.” This program consists of allocating resources so that farmers can plant timber and fruit trees, often from army nurseries, and in exchange, they receive a subsidy for their crops. However, one of the requirements of this social program is that farmers and Indigenous people register two hectares of private property in their name, which represents a continuation of the neoliberal agrarian reform aimed at further privatizing land, contrary to the logic of communal ownership. This leads many of these young people to sell their land to new landowners and use the money to pay the coyote, the person who smuggles them into the United States. But there, they encounter a terrible immigration policy that expels them, and they return directly to Mexico landless, indebted, and easy prey for organized crime.

Precisely, from countries like Colombia and Ecuador, among others, there are warnings about drug trafficking groups occupying territories that were part of the networks of autonomous indigenous communities. What is happening with this phenomenon in the region influenced by Zapatismo?

While drug trafficking is one of the most important sources of income for these networks in Mexico, today organized crime groups have human trafficking as their main business, as part of the new phenomenon of global exodus, something that is combined with a terrible crisis of missing persons. Currently, in the country, we have nearly 140,000 missing persons, about 500,000 murdered, around 1 million displaced people, and 13 femicides every day. In this context, since 2018, there has been a greater presence of organized crime groups in indigenous communities, and with it, the emergence of young people from these communities with problems of addiction to synthetic drugs. In this context, Zapatismo finds itself in a kind of bubble, in a kind of peace zone, since in its territories there are no forced disappearances, no drug trafficking, no human trafficking, none of these horrors that occur in the rest of the country because it has managed to protect itself through organizational and community work, just as also happens in Ostula in Michoacán and in communities in Guerrero belonging to the Emiliano Zapata Indigenous and Popular Council.

______________________________________

Raúl Romero Gallardo is a Mexico City-based sociologist, Latin Americanist, and academic technician at UNAM Social Research Institute. He teaches at the Faculty of Political Sciences, as well as at UNAM. As a Zapatista sympathizer and anti-capitalist militant, he is a Red Universitaria Anticapitalista member. He co-coordinated the book Resistencias locales, utopías globales (2015) and writes frequently for the Mexican newspaper La Jornada. His topics of interest include anti-capitalism, social movements, autonomies, socio-environmental resistance, emancipatory processes, and criminal economies.

Para leer la entrevista en español, haga clic aquí en ZUR. To read the original version in Spanish, click ZUR here.

10th CompArte Zapatista : Rebel Culture with Community | Aug 30 at Peralta Park in Oakland

The 10th CompArte: The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival

The Chiapas Support Committee invites you to celebrate our stuggles and movements for peace, justice & in solidarity with the Zapatistas at the 10th CompArte zapatista, The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival!

The 10th CompArte zapatista will be held on Saturday, August 30, 2025, 2:00-5:00 pm, at the Peralta Hacienda Historical Park in Oakland, California.

CompArte will feature poets, son jarocho, social justice music and speakers giving updates on crucial movements for land justice in Mexico and on the Zapatistas. There will be tamales, community vendors and artesanía Zapatista to enjoy the afternoon.

Bring a blanket, snacks (NO alcohol or drugs) and your-workers, neighbors, friends and family to enjoy an afternoon of rebel culture in a community of communities with beautiful words, sounds and art.

Featured Performers

Ayodele Nzinga, Oakland Poet Laureate

Francisco Herrera, justice music sin fronteras

Josiah Luis Alderete, poeta pocho, Medicina portal-keeper

Elizabeth Jiménez Montelongo, La raíz artist & poet

Dúo Madelina y Fernando | Latin America canción nueva/New Song

Jaraneros de la Bahía | Son jarocho music!

Sara Borjas, Xicana poet

Mo Sati, Palestinian poet

Plus other artists & performers!

Live Painting: Daniel Camacho | Art Display Hussam Hamad

Local community vendors:

Annette Oropeza “Adoro Jewelry,” Xochitl Guerrero “Taller Xochicura Art,” Cafe y Rebeldía (zapatista coffee), Medicine for Nightmares Bookstore, Elizabeth Jiménez Montelongo Art

CSC offering: Artesanía zapatista!

The 10th CompArte zapatista is organized by the Chiapas Support Committee in partnership with the Peralta Hacienda Historical Park in Oakland, California.

Please join us for an intimate gathering of community, good words and music at the 10th CompArte zapatista in Oakland on Saturday, August 30, 2-5 pm at Peralta Park.

***

Donate to uplift the work of the Chiapas Support Committee

¡Gracias! Thank you!.

Rebel art & the justice that comes from below

By Gloria Muñoz Ramírez

“The EZLN has plenty of ideas about what an organized and free people looks like. The problem is that there isn’t a government that obeys you, but rather a bossy government that ignores you, that doesn’t respect you, that thinks Indigenous peoples don’t know how to think, that wants to treat us like bare-foot Indians. But history has already given them back and shown them that we do know how to think and that we know how to organize ourselves. Injustice and poverty make you think, they generate ideas, they make you think about what to do, even if the government doesn’t listen to you,” said Major Moisés, in a 2003 interview with this journalist.

More than 20 years later, the now Subcomandante Moisés, the highest-ranking military commander within the Zapatista structure, continues to explain, alongside the Captain, the horizon of their struggle. Many theories have been put forward about the more than 30-year public history of the predominantly Mayan army that challenged the powers that be in January 1994. But nothing can be understood without the daily practice of their struggle. Autonomy, or however each person defines it, is a difficult internal construction and often invisible to the outside.

During the recent Rebel and Reveal Art Encounter, convened by the EZLN in rebel territory and at the CIDECI (Center for Research, Development and Comprehensive Training — Centro de Investigación, Desarrollo y Capacitación Integral) in San Cristóbal de las Casas, among many other performances, the play “Nature Reveals and Rebels,” was featured. In this performance, very young Zapatista men and women, disguised as pumas, bees, roosters, trees, peacocks, butterflies, fish, penguins, snails, tigers, pumas, lions, macaws, bears, zebras, turtles, and other natural beings, staged the defense of Mother Earth.

In approximately one hour, in addition to the message about non-property and the Common to face each anti-capitalist challenge, the internal organization of hundreds of communities was deployed to make the play happen. The actors are surely from different communities. How were they chosen? How did they get to the rehearsals? What difficulties did they face? What happened in the communities during the rehearsals? Who created the costumes? How many hands made them? What if there was no money? How long did they rehearse their lines? Did they laugh a lot? Paulo Freire would surely have jumped for joy. Autonomous organization in its splendor to raise awareness both internally and externally.

“It’s a work of young Zapatistas, which they invented because they said, ‘No one listens to us, and maybe this way they’ll listen to us, understand what we want, the future we want for ourselves, our children, and those who follow,” explained Subcomandante Moisés at the start of the enormous wildlife-parade that occupied the Caracol Jacinto Canek esplanade.

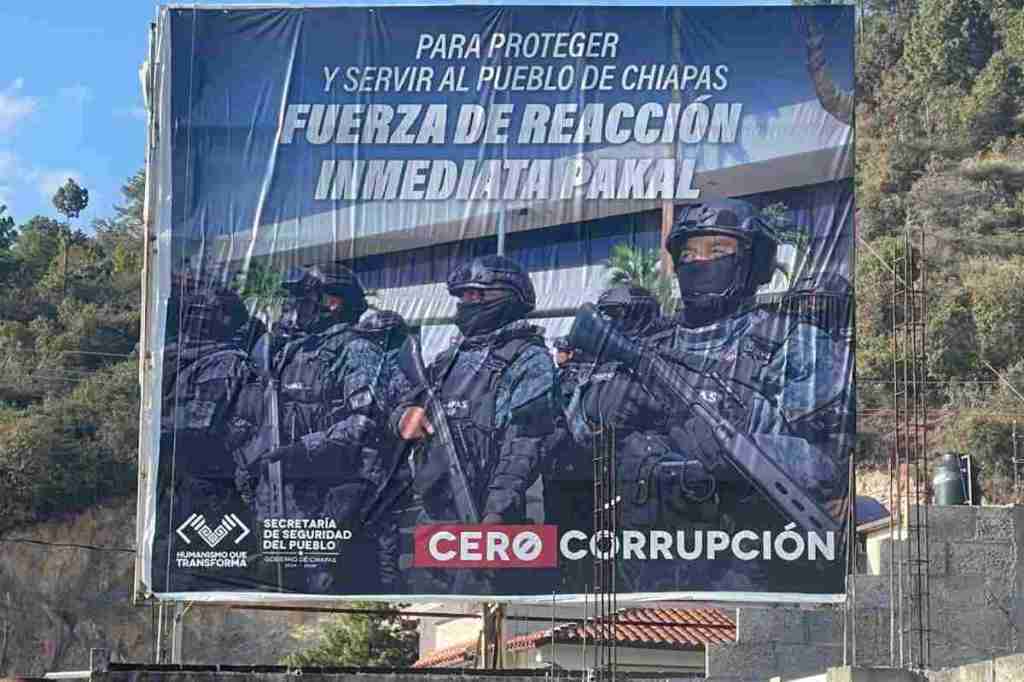

The same work was carried out at the CIDECI center in San Cristóbal de las Casas, where the Zapatistas denounced the presence of the National Guard and the Pakal Rapid Response Forces (FRIP, Fuerzas de Reacción Inmediata Pakal) in the vicinity of the second meeting venue on April 19, 2025.

The justice that comes from below.

A few days later, following artistic demonstrations by Zapatista communities and other regions around the world, an arbitrary incursion by members of various police forces and the National Guard took place in a community with Zapatista support bases.

The events, reported by the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba), are as follows: “On April 24, 2025, around 3:30 p.m., in the community of San Pedro Cotzilnam, official municipality of Aldama, Chiapas, Vicente Guerrero Autonomous Region, in a strong joint operation with around 39 vehicles from the National Guard, Mexican Army, Pakal Rapid Response Forces, the Ministerial Intelligence Investigation Agency, the State Preventive Police, the Secretariat of Security and Citizen Protection of the Federal Government, accompanied by two vehicles with armed civilians, carried out searches without judicial warrants in the homes of Zapatista support base families. They violently broke into the houses, detaining the Tsotsil compañeros José Baldemar Sántiz Sántiz, 45 years old, and Andrés Manuel Sántiz Gómez, 21 years old, and then the convoy continued towards the municipality of San Andrés Larráinzar.”

After 55 hours of being reported missing, Frayba documented that the two Zapatistas were brought before the Control Court and Trial Tribunal of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, accused of aggravated kidnapping. The arrests were carried out without judicial authorization and, according to Frayba, they received cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. State forces also raided homes, stole belongings, and sowed panic.

And this is where the Zapatista autonomous justice system comes in, and the fateful story takes another turn. While countless national and international pronouncements were made demanding the release of the two detainees, the autonomous authorities carried out their own investigation. This was, once again, a demonstration of their daily work, sometimes visible, as on this occasion, but mostly unannounced. Once again, it was Subcomandante Moisés who explained what had happened, but not before clarifying that in Zapatista zones “attacking the life, liberty, and property of others is prohibited… And in the case of murder, kidnapping, assault, rape, forgery and robbery, these are serious offenses. In addition, there are offenses against drug trafficking, its production, and consumption. Also, drunkenness and other offenses are determined to be common offenses.”

The Zapatista investigators confirmed that their two companions were innocent, but since there had indeed been a kidnapped person, they delved into the matter until they found two perpetrators. After their confessions, they were detained by the autonomous authorities, respecting their human rights, and later handed over to Frayba. But not before determining where the body had been buried, since they had not only kidnapped a man, but also murdered him.

“The government at all three levels knew all of this, but did nothing. Instead of immediately releasing our innocent compañeros, they dragged their feet and proposed an exchange of prisoners. This way, they could bribe the media and sell them the story that it was all the work of state and federal justice. And they could also keep what they stole from the poor indigenous people who suffered their attack,” Moisés said in a statement.

In the early hours of May 2, the confessed murderers were handed over to Frayba, and the human rights center channeled them to official authorities. That same day, with no choice, they released Baldemar and Andrés. Frayba and the mobilization, of course, did their part.

The outcome not only highlighted the prevailing lack of justice, but, above all, the ethical, courageous, and forceful exercise of a movement that remains a global benchmark.

The question of what the Zapatistas are doing could be answered by what happened in the last 15 days, between April 13 and May 2, 2025.

__________________________________________________________________________

Rebel art & the justice that comes from below by Gloria Muñoz Ramírez was published in the original Spanish by Ojarasca, a supplement of La Jornada, available here.

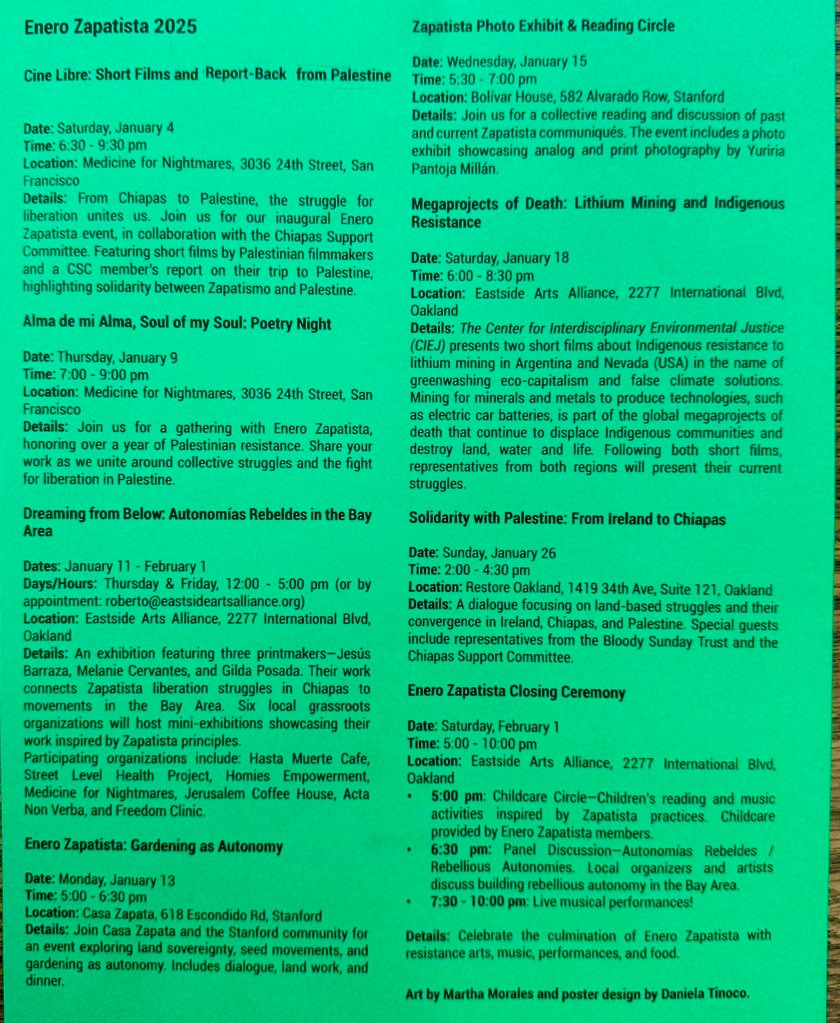

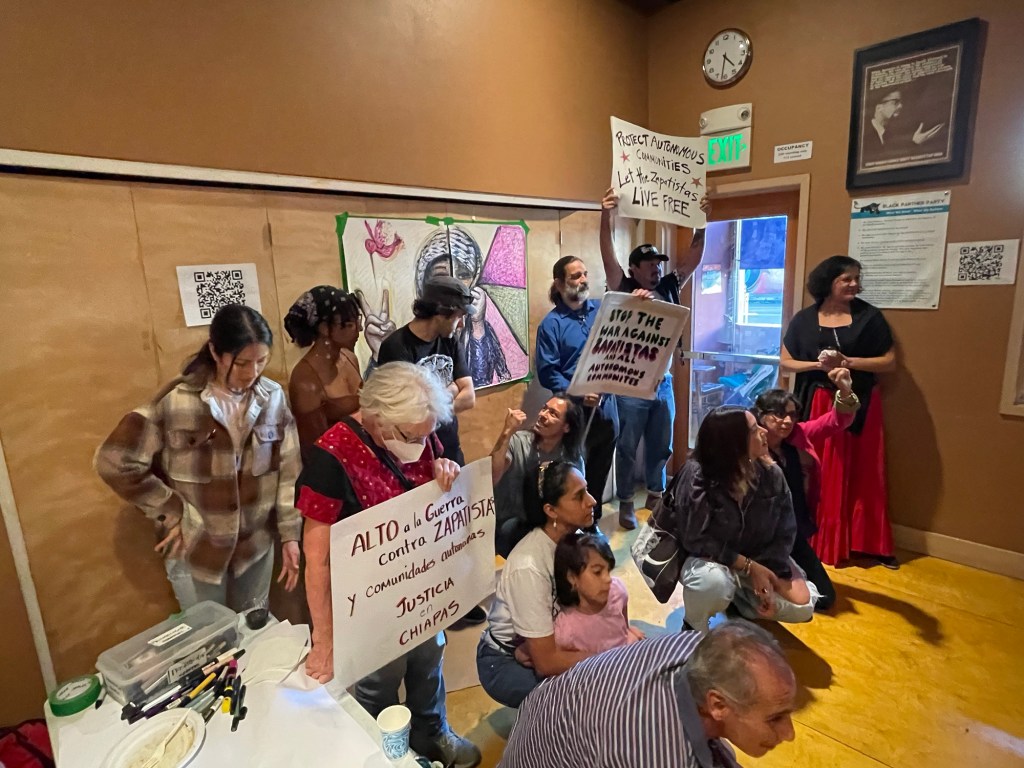

Enero Zapatista | Tending to our dreams from below: Rooted in zapatismo

Enero Zapatista 2025

Tending to our dream from below:

Rooted in Zapatista Principles

A group of individual activists, community-based organizers and collectives based in Oakland, San Francisco and other parts and cities of the Bay Area have organized the second annual Enero Zapatista, “Tending to our dreams from below: Rooted in the Zapatista Principles,” a month-long series of gatherings and forums with art, poetry, music, discussions of land justice, sovereignty and solidarity from Chiapas to Palestine. (See Enero Zapatista calendar below.)

Cine Libre: Short FIlms & Reportback from Palestine

Starting on Saturday, January 4, 2025 (6:30-9:30pm), Enero Zapatista will kick off the month of actitives with “Cine Libre: Short Films & Reportback from Palestine.” featuring a series of short films by Palestinian artists and film-makers that probe the inersections of art, culture and resistance in the mulfaceted struggles facing the Palestinian people under brutal occupation, facing genocide and the seige of Gaza now in its 15th month. A member of the Chiapas Support Committee, who attended as part of a Sexta Grietas del Norte delegation an international gathering in Palestine, will be giving a reportback. Cine Libre will be held at the Medicine for Nighmares Bookstore & Gallery in San Francisco. Click here for more information.

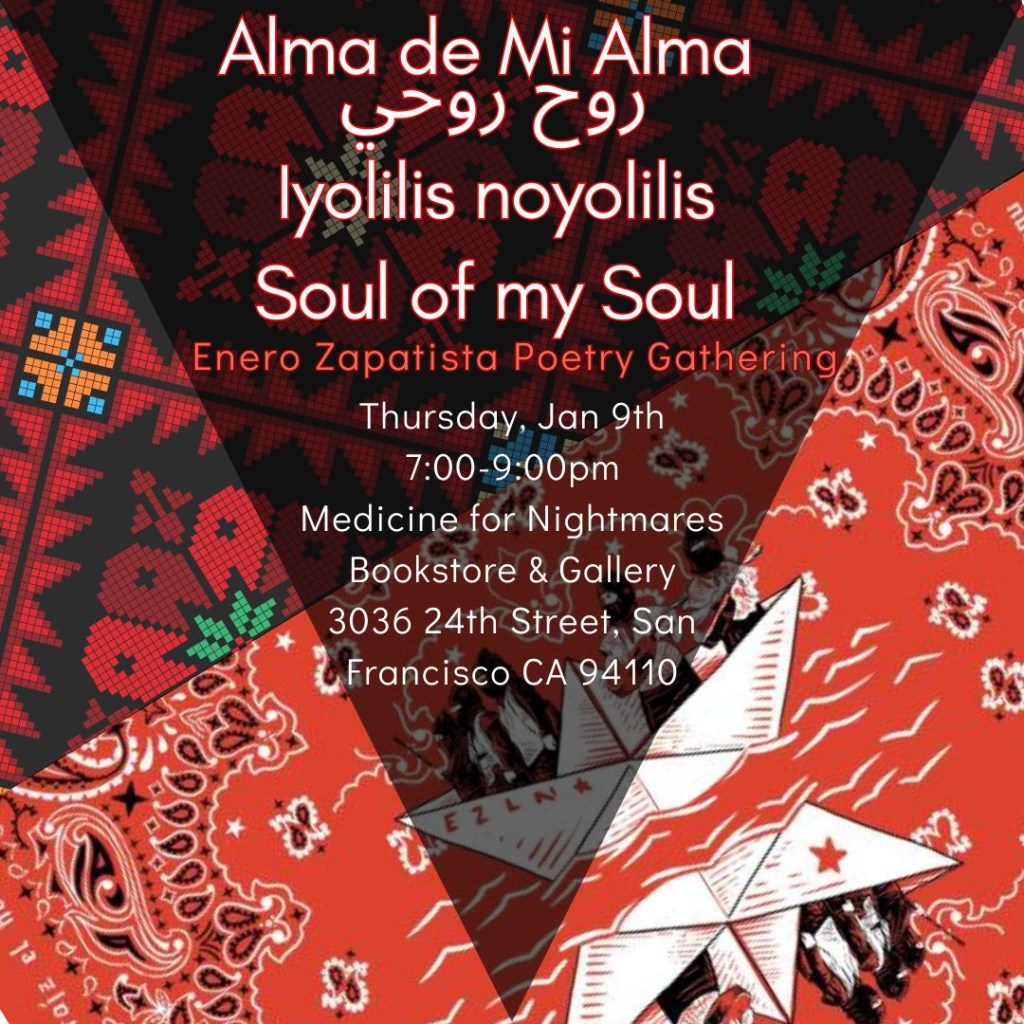

Alma de Mi Alma, Rouh il Rouh, Iyolilis noyolilis, Soul of my Soul: Enero Zapatista Poetry Night

Join us for a very special night of music and poetry centering the struggles for liberation that unite us from Chiapas to Palestine. Featuring poets and musicians from across the Bay Area: Arnoldo García, Camellia Boutros, Dina Omar, Evelyn Donaji Arellano, Josiah Luis Alderete, Leora (Lee) Kava, Leslie Quintanilla, Lorene Zouzounis, Lubna Morrar, Mo Sati, Sara Borjas, Sara O’Neil, and Stevie Redwoo

Soul of my Soul will be space to remember and commemorate our martyrs in the struggle for liberation in Palestine. May we honor memory and imagine other worlds by finding connection and inspiration in the Zapatista’s principles, the Palestinian people’s steadfast resistance to occupation and the Zapatista’s call for solidarity in our common struggles.

Enero Zapatista 2025 Calendar

To view the Enero Zapatista 2025 schedule online visit their Instagram blog @enerozapatista.bayarea.

Rightwing violence rising with impunity against Zapatista communities

Send messages, photos, videos and art in solidarity with the Zapatista communities and to denounce the State violence and government-backed paramilitary and narco gang attacks on the Zapatistas, demanding justice and a dismantling of the paramilitary and narco gangs to: porchiapaz@gmail.com

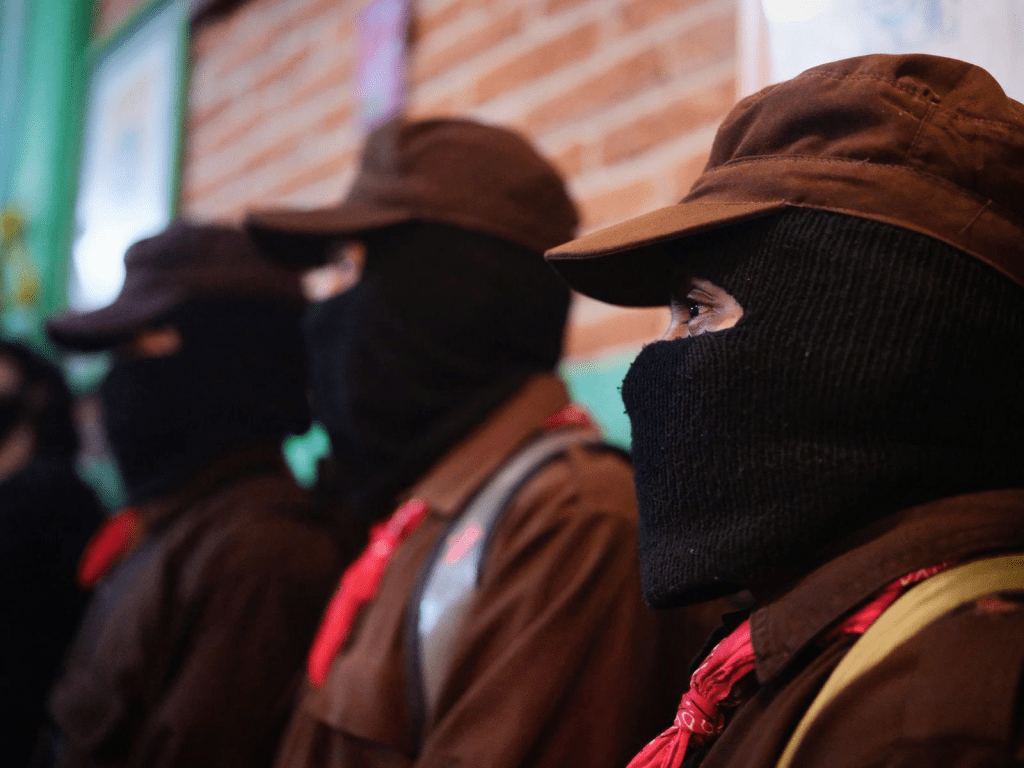

A report by the Chiapas Support Committee

The Zapatistas have maintained autonomous self-government in their territories in Chiapas ever since the successful and unexpected uprising of 1994. Last year, for the third or fourth time since that uprising, the Zapatistas announced a major restructuring of their organization of autonomy. They explained that the system of juntas and municipal zones had resulted in an overly hierarchical structure, and they were abolishing the juntas and inverting the pyramid of power so that the communities had more decision-making power at the base. The new governing entities, called Local Autonomous Governments, (Gobierno Autónomo Local or GALS) have been created at the community level. Traveling through Chiapas these days one see signs for GALS everywhere in Zapatista territories.

The Zapatistas contend that the new structure inverts what had evolved into a pyramidal structure. Formerly, communities would send representatives to the municipalities, then from the municipalities, representatives would be sent to the juntas at the caracol/zone level. Decisions made at the junta level would then go back down to the communities. The establishment of the GALS was to provide structure by which certain decisions would be made directly in communities themselves. We do not know what areas of decision-making are being relegated to the communities, but in a recent trip to Chiapas by members of the Chiapas Support Committee (CSC), we had several conversations that led us to believe that the new structures had reactivated and remotivated compas in the communities. For example, in one Caracol, since the restructuring, many more young people have been volunteering as health promoters, perhaps because they were motivated by discussions in their community GALs.

This major restructuring is remarkable, though not atypical of the Zapatistas, who have reinvented themselves several times over their 30 years of self-government. It is the only revolutionary, anti-capitalist organization that regularly, self-consciously, takes on the task of studying and restructuring their power structures. These recent changes were the result of years of discussions at the community level.

One other important change has been the consolidation of the ethos of the commons ” lo común” and a commitment to “non-property” (la no propriedad). The changes have enabled Zapatistas in mixed communities to work together with their non-Zapatistas neighbors. The collective working of the land was singled out as an area of “the commons” to be developed. As long as they weren’t paramilitaries or working with organized crime, neighbors of Zapatistas would be invited to collaborate on working the land, with the proceeds to be shared amongst them. In the past, Zapatistas could not work together with non-Zapatistas, even though in many cases they lived next to each other in villages where the population was mixed. There are a number of places in Zapatista territory where people have left the organization for various reasons, not necessarily, and not even preponderantly because they disagreed with the principles of Zapatista community, but because they wanted more freedom to do things like attend state schools or travel. (Zapatistas can only attend their own Zapatista schools, they are not allowed to go to official state schools).

CSC believes this restructuring is a very positive change that will lead to new collaborations. The Chiapas Support Committee recently submitted a proposal to the Zapatistas to collaborate with Zapatista communities to bolster their autonomous health system. More on that when we hear back from the compas

ATTACKS AGAINST ZAPATISTA COMMUNITIES

Zapatistas have been suffering increasing attacks from criminal groups attempting to take over their lands. Earlier this year, the two remaining Zapatista families in Nuevo San Gregorio were forced to relocate after years of attempting to defend themselves against constant aggression by armed groups. More recently, in the community of 6 de Octubre, gunmen have entered Zapatista land and are threatening the families and beginning to build homes on the Zapatista’s land. These alarming developments occur with complete impunity, despite repeated denunciations and appeals for justice.

The security situation in Chiapas has been deteriorating for years now, most notably since Covid. The presence of organized crime has reached every corner of Chiapas. There have been turf wars between the infamous Sinaloa and Jalisco Nuevo Generación drug gangs and a plethora of smaller well-armed criminal groups sprouting all over the state. For a while there was confusion about the allegiances of armed groups who called themselves “autonomous,” who claimed to be protecting the local campesinos and, in some cases, even stated their support for the Zapatista “brothers.” By now it is clear that most of them are just another group fighting for power and wealth at the expense of the communities, most likely supported by local caciques with connections to organized criminal groupings. Disappearances, beatings and jailing of activists and anybody who speaks out have dramatically increased under the governance of the so-called 4th Transformation, inaugurated by former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the MORENA party. Despite the constant reporting of incidents, AMLO has continued to insist that Chiapas is safe, that the violence is in-fighting between different indigenous groups. There has been little or no response from the State to bring criminals to justice at any level of government.

On the national front, AMLO’s party won the recent elections by a landslide, having won over much of the so-called left. He was very clever in apportioning out economic advantages to particular sectors, like students and the elderly, winning over huge swathes of the population. Although his rhetoric claims to be critical of neoliberalism, his acts speak all to the contrary. His successor and protege, Gloria Scheinbaum, looks to be just more of the same.

In the Southeast of Mexico, in particular, it is very clear that the capitalist compulsion to transform all social relations into money relations to the benefit of the capitalist class is the main agenda of the MORENA Party. The Morena administration has perpetrated massive devastation of the natural environment, including some of the most important forests in the Americas, through his obsession to construct the cynically-named “Maya Train.” AMLO’s policies and social programs, such as the so-called Sembrando Vida, have wreaked havoc in indigenous communities and caused the disintegration of traditional forms of indigenous life that prioritized community and agriculture. The National Guard, a new military formation that AMLO created supposedly to assist in protecting people from organized crime, is now clearly just another player in the criminal gang landscape and seems to be deployed primarily in the harassment and abuse of immigrants. In San Cristóbal, they patrol downtown regularly but whenever there is a shooting event, like the time the market was held hostage by gunman for four hours, the National Guard is nowhere to be seen. (The same is true of federal and municipal policing entities). AMLO has handed over to the military powers over civilian life unprecedented in Mexico, notably handing over to them the management of the new airport and the Maya Train.

MORENA’s strategies are designed to pave the way for big capital to enter the area and exploit the “natural resources,” including the labor pools available in the area–from peasants displaced from their lands to make way to natural resource exploitation, to the waves of migrants crossing the Guatemala border. International capital has been invited to join the party. The Zapatistas and other like-minded indigenous communities such as those belonging to the Congreso Nacional Indígena, (CNI, National Indigenous Congress), are in their way. Because in order to turn these largely indigenous areas into fodder for capitalist exploitation, the communities that have inhabited these lands despite 400 years of colonization, must be torn apart.

LATE BREAKING NEWS:

CSC announces here our horror at the assassination in plain daylight of Father Marcelo Pérez Pérez as he was on his way from one mass at the Iglesia de Cuxtitali to another at the Iglesia de Guadalupe in San Cristóbal de las Casas (Sunday, October 20, 2024). Father Pérez was known for his public defense of Indigenous and labor rights and for his open criticism of organized crime. He had to move to San Cristóbal from his native Simojovel due to threats against him by organized crime in that area. This brazen assassination of a beloved priest in broad daylight on the streets of San Cristóbal is unprecedented and indicates a new level of violence on the part of organized crime.

____________________________________________

This report was written by members of the Chiapas Support Committee.

PLEASE TAKE ACTION: Send messages, photos, videos and art in solidarity with the Zapatista communities and against the State and government-backed narco and paramilitary violence against the Zapatista communities. Send them to porchiapaz@gmail.com

CompArte : The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival | Oakland 2024

The Chiapas Support Committee presents the ninth annual CompArte: The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival to celebrate our movements and struggles for justice, peace and in solidarity with the Zapatistas and the Palestinian liberation struggle against genocide and occupation.

On Saturday, October 19, 2024, from 2:00-5:00pm (doors open at 1:30pm), at the Eastside Cultural Center (2277 International Blvd, Oakland, CA 94606), our commuity will gather to enjoy music, poetry, art and each other’s company and weave our dreams together in the sounds and rhtyhms of our movements.

CompArte started in the summer of 2016, when the CSC joined the Zapatistas’ call to convene justice artists and culture-maker warriors for liberation to bring their art, music, graffitti, music of all genres, dance, movement, film, theater and poetry together to join in the fight against capitalism. CompArte has been held every year since then and during the pandemic, the CSC held three sessions of CompArte on-line drawing in a local, regional, national and international audience sharing their work through the screens. CSCS has held ComParte at the Omni Commons, Peralta Park and with the support of the Eastside Arts Alliance over the last two years at the renown Eastside Cultural Center.

CompArte artists & performers

POETS

Persis Karim is a poet, essayist and editor as well as professor. She teaches Comparative and World Literature at San Francisco State University, where she also serves as the director for the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies. She is the editor of three anthologies of Iranian diaspora literature and has written numerous articles about Iranian diaspora literature and culture. Her poetry has been published in national publications such as Callaloo, Green Linden Press, Porter Gulch Review, Caesura, Nowruz Journal, The New York Times, and Reed Magazine. She has just completed co-directing/co-producing her first film, “The Dawn is Too Far: Stories of Iranian-American Life,” which is a documentary about Iranian Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area. Read and listen to Persis Karim poems: The Seed Collector’s Daughter, Comprehension, and Pomegranates

Mo Sati was born in Palestine, grew up in a refugee camp in Jordan, and now lives in Oakland. Mo is a poet, a writer, a playwright, and an artist. He participates in activist and cultural events nationally and internationally sharing insights about life as a refugee uprooted from his homeland. His poetry, writings, and artworks tell stories of the people of Palestine living under occupation. His work personifies emotions drawn from the day-to-day struggles of resistance to oppression as Palestinians fight to unshackle themselves from decades of military occupation. Mo’s play, a satire, “The Ice Cream War” will be presented by the Eastside Arts Alliance in a stage reading on Friday, October 25, 2024, &;00pm at the Eastside Cultural Center. You can also hear Mo read his poetry accompanied by saxophonist Daniel Heffez here. Follow Mo Sati’s work on Instagram here.

Darius Simpson is a writer, educator, performer, and skilled living room dancer from Akron, Ohio. He received an MFA in Creative Writing-Poetry from Mills College. Darius was a recipient of the 2020 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship, a 2023 National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and is the author of Never Catch Me (Button Poetry, 2022). He hopes to inspire that feeling you get that makes you frown and slightly twist up ya face in approval. Darius’ poems have appeared in POETRY Magazine, The Adroit Journal, American Poetry Review, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and others. Darius believes in the dissolution of empire and the total liberation of all oppressed people by any means available. Free the People. Free the Land. Free All Political Prisoners. You can read work by Darius Simpson here.

MUSIC

AntiFaSon is a Son Jarocho project, a musical guest on Ohlone territory (aka Oakland). They amplify anti-capitalist, anti-colonial, anti-fascist and anti-extractivist feminist themes in Son Jarocho songs that form part of the larger history of Afro-Indigenous land, water and campesinx struggles. AntiFaSon will be performing with Corazón de Cedro. Follow AntiFaSon on Instagram: @somosantifason

Corazón de Cedro is an all-femme Son Jarocho and Arabic folk musical project based in San Francisco, California. The group’s arrangements explore the connection between Arabic and Mexican folk musical traditions through the Arabic oud, the jarana Jarocha, zapateado and more. Corazón de Cedro aims to serenade the diasporic heart through melodies, rhythms and poesia that speak of love, resilience, and our shared struggle for collective liberation. Featuring special duet by Evelyn Donají & Camellia Boutros. Corazón de Cedro will be performing with AntiFaSon. You can connect with Corazón de Cedro on Instagram here.

Davíd de la Gran writes: Un Musico Pobre. A community oriented musician/ composer of Garifuna-Caqchiquel-Ladino descent buscando su lugar y su voz en este mundo and finding it only by looking within. Davíd de la Gran on Instagram here.

Mónica María Fimbrez’s music reflects her Californian roots mixed with traditional, earthly and contemporary sounds of Latin America. A vocalist, multi instrumentalist and composer, her songs are innovative and expressive of a world where cultures coexist, where fear is transformed by compassion, where we learn to truly love ourselves, and where we view the world from an empathetic and holistic state of mind. Read more about Mónica María here and on Instagram.

Francisco Herrera Theologian, Cultural Worker, Singer-Songwriter, Francisco Herrera has produced seven albums (includes two children’s music in Spanish), writes scores for film and theater, working with producers like the late great Saul Landau. He has shared the stage with the Jon Fromer, Pete Seeger, Emma’s Revolution at mass actions as School of America’s Watch (up to 22,000 people), and the Battle for Seattle, with over 250,000 people shutting down the WTO in 1999 and massive demonstrations across the country. In 1987, Francisco shared the stage with Joan Baez and Jessie Jackson before 10,000 people there to bring attention to the brutal attack on Vietnam Veteran and Peace Organizer, Brian S. Willson, after the Navy Commander at Concord Naval Weapons Station gave the order to run over the protestors. However, Herrera’s most common place is not on big stages. He was actually at the small Nuremberg Peace Action when Brian was run over by the train. So close, in fact, that he was subpoenaed as the witness closest to Brian, David and Duncan. He can be found in intimate gatherings of women recovering from domestic violence, day laborers organizing for a universal wage, children becoming bilingual (Spanish/English), Interfaith groups shutting down private prisons; always performing uplifting and energizing songs that move, teach and inspire. His Latest album Honor Migrante crosses physical and musical borders to expose the grace and beauty of the migrant community as all of us with a rocking sound that brings together regional music from Mexico and the U.S. with a “Chicano Soul” style that permeates his eclectic choice of music. Learn more about Francisco Herrera online here.

Duo Madelina & Feña features multi-instrumentalist composer and writer Fernando Torres and multi-faceted puertorican Singer/interpreter and political activist Madeleine Zayas. Their eclectic repertoire is rooted in the Nueva Canción/Nueva Trova tradition of entertaining and educating about culture and pressing social issues.

Madeleine Zayas Born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Madeleine Zayas is a Latin American singer/interpreter, dancer and choreographer and architect based in Oakland. She was co-founder of Buena Trova Social Club in 2012 and lead singer and co-artistic director of Madelina y Los Carpinteros since 2014. Madeleine has performed in San Juan, Puerto Rico, many U.S. Cities, and Santiago, Chile, and has shared stage with Wilkins, Cheo Feliciano, Inti Illimani, John Santos and Holly Near. She believes in art and cultural activism as a positive force of communication and a tool for social change.

Fernando Feña Torres is a Chilean exile, musician, composer and poet, journalist and founding ex member of Grupo Raiz. Fena is an expert in folkloric multi-instrumentalist. He began his musical career as a young boy inspired by the socialist government of Salvador Allende A former political prisoner and exiled into the U.S., he has collaborated with Teatro Campesino and has performed in Bay Area and internationally along with artists such as David Byrne, Pete Seeger and Holly Near.

To listen to Madelina y Feña’s new song for Gaza click here Would You

Listen to Madeleine Zayas in a live performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7j5JOiLPVfM

ART

Daniel Camacho is a prolific painter and muralist. He paints mobile murals that can be and displayed at cultural gatherings, picket lines and marches and meetings. Camacho studied visual arts at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in San Carlos, National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City and Painting and Sculpture at the National Institute of Fine Arts in Mexico City. He currently teaches Mexican and Latinx art to elementary and middle school students in the Bay Area. Daniel’s mural and bas relief work can be seen on different walls of Oakland’s Fruitvale District and in the Oscar Grant Plaza next to the Fruitvale BART Station. Follow Daniel Camacho’s art and work on Instagram here.

CompArte: The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival organized by the Chiapas Support Committee with the support of the Eastside Arts Alliance.

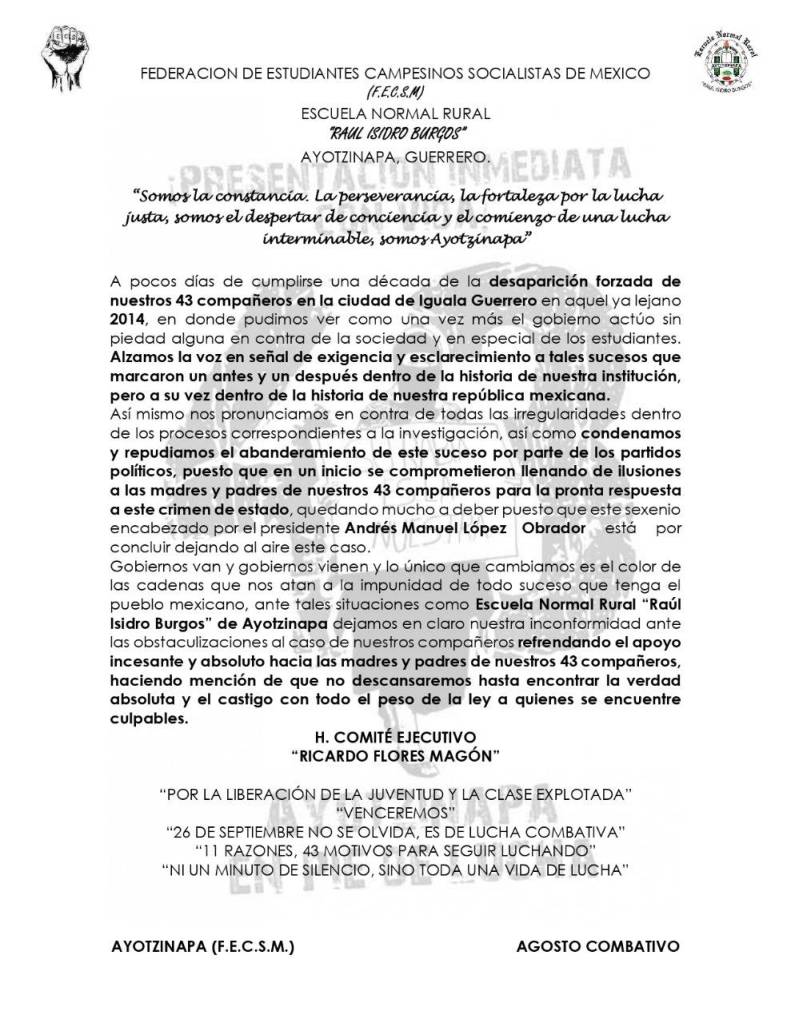

The normalistas denounce: The AMLO presidency is about to conclude leaving the Ayotzinapa case “in the air”

Students from Ayotzinapa Normal denounced the six-year Presidencial term limit of Andrés Manuel López Obrador “is about to conclude leaving in the air” the disappearance of the 43 classmates who on the 26th of September will mark 10 years without truth and justice despite it being one of the federal governments campaign promise to solve the case.

“We speak against all irregularities within the processes corresponding to the investigation, as we condemn and repudiate the flagging of this event by the political parties, since at the beginning they committed themselves by filling the mothers and fathers of our 43 colleagues with hope for the prompt response to this State crime, leaving much to owe.“ said the normalistas in a statement.

Normalistas from the Ayotzinapa College will not rest until they find the absolute truth and the punishment with the full weight of the law for those found guilty.

“Governments come and go and the only thing that changes is the color of the chains that bind us to impunity for every event that the Mexican people have,” students added.

The students reaffirmed their support for the parents of the 43 missing students and assured that they will not rest until they find “the absolute truth and the punishment with the full weight of the law for those found guilty.”

The full statement follows:

FEDERATION OF SOCIALIST FARMER STUDENTS OF MEXICO

(F.E.C.S.M)

RURAL TEACHER’S COLLEGE

“Raúl Isidro Burgos“

A few days before the 10th anniversary of the forced disappearance of our 43 colleagues in the city of Iguala, Guerrero, in that distant 2014, we are seeing how once again the government acted without any mercy against society and especially against the students. We raise our voices in demand and clarification of these events that have marked a before and after in the history of our institution, but at the same time within the history of our Mexican republic. Likewise, we speak out against all the irregularities within the processes corresponding to the investigation, as well as condemn and repudiate the using of this event by the political parties, since at the beginning they promised to fill the mothers and fathers of our 43 colleagues with hope for a prompt response to this state crime, leaving much to be done since this six-year term headed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is about to conclude, leaving this case in the air.

Governments come and go and the only thing that changes is the color of the chains that bind us to impunity for every event that the Mexican people have suffered. In situations such as the “Raúl Isidro Burgos” Rural Teachers’ College in Ayotzinapa, we make clear our dissatisfaction with the obstacles to the case of our colleagues, reaffirming our unceasing and absolute support for the mothers and fathers of our 43 colleagues, underscoring that we will not rest until we find the absolute truth and punish those found guilty with the full weight of the law.

H. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

“RICARDO FLORES MAGÓN”

“FOR THE LIBERATION OF YOUTH AND THE EXPLOITED CLASS”

“WE WILL WIN”

“SEPTEMBER 26TH IS NOT FORGOTTEN, IT IS A COMBATIVE STRUGGLE”

“11 REASONS, 43 REASONS TO CONTINUE FIGHTING”

“NOT A MINUTE OF SILENCE, BUT A LIFETIME OF STRUGGLE”

AYOTZINAPA (F.E.C.S.M.) COMBATIVE AUGUST

____________________________

Translated by the Chiapas Support Committee. Originally published by Desinformémonos, August 22, 2024. Click here for the original.