Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Chiapas and the Zapatistas face a dramatic increase in violence

By: Mary Ann Tenuto-Sánchez

When discussing the increased violence in Chiapas, it’s helpful to remember that there is a neoliberal effort underway, promoted by the World Bank, to bring indigenous peoples in southeast Mexico into the capitalist marketplace. The vehicle for bringing this about is a massive infrastructure development plan, originally named the Plan Puebla-Panama and then re-named the Mesoamerica Project. It’s also helpful to remember that Chiapas is Mexico’s southernmost state and has an extensive border with Guatemala, one of the Northern Triangle countries in Central America, which expel both migrants and contraband into Mexico, thus contributing to the violence that takes place.

Media reports and analysis, Zapatista communiqués and anecdotal stories from Chiapas residents indicate increased violence due to the following sources: counterinsurgency (low-intensity war against the Zapatistas), the presence of national organized crime cartels, the San Cristóbal to Palenque superhighway, municipal elections and migration.

Counterinsurgency – “Low-Intensity War against the Zapatistas”

After the 1994 Zapatista Uprising, the Mexican Army was in charge of counterinsurgency actions to capture, contain and repress the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN). A February 1995 Army offensive against the Zapatistas brought about massive civil society demonstrations throughout Mexico in support of the Zapatistas and a negotiated peace in Chiapas. The Mexican Congress responded to civil society by enacting the “Law for Dialogue, Conciliation and Dignified Peace in Chiapas,” published in the Diario Oficial (the official government bulletin) on March 11, 1995. It amounted to a truce between the Mexican Army and the EZLN. After this law was signed, we saw paramilitary groups emerge, replacing the Mexican Army’s role of armed counterinsurgency. Those paramilitary groups have continued in one form or another to this day, sometimes active and at other times dormant. In the last three or four years we have seen an increase in paramilitary activity.

Paramilitary violence aimed directly at the civilian Zapatistas has clearly increased in intensity and frequency in specific areas: Aldama (Caracol 4, Oventik) and Nuevo San Gregorio, as well as surrounding communities in Lucio Cabañas Autonomous Municipality (Caracol 10 Patria Nueva). Both involve disputes over land and frequent armed attacks.

In Aldama, the attacks are several times a day every day from paramilitary groups in Santa Martha, Chenalhó. Seven residents of Aldama have been killed by gunfire and others have been injured or have died from illness caused by the conditions they suffered during forced displacement. According to press reports, some of the same paramilitaries who perpetrated the 1997 Acteal Massacre are involved, but now with a younger generation added. Aldama is the official name of the municipality. The Zapatistas are organized in Magdalena de la Paz autonomous municipality (Caracol Oventik) within the official municipality of Aldama.

In Nuevo San Gregorio, the armed attacks are frequent and aimed at taking land, crops and animals away from the community. Attackers are members of the Regional Organization of Ocosingo Coffee Growers (ORCAO, its Spanish acronym). Residents of Nuevo San Gregorio refer to them as “The 40 Invaders.” The origin of the conflict with ORCAO is an old one and attacks have happened off and on for almost 20 years, but the frequency and intensity have increased over the last 2 or 3 years and also extend to other communities within the Lucio Cabañas autonomous municipality.

Importantly, no level of government intervenes in these attacks! No level of government has intervened to stop the attacks in Aldama, where the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) has issued precautionary measures. No level of government has intervened to stop attacks in Nuevo San Gregorio, where the aggressor group has also threatened human rights observers. The threats against observers were such that the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) took the unusual step of withdrawing observers from a community in conflict. These attacks on Zapatista communities are denounced by human rights and solidarity organizations and reported in the press. Of concern is whether there are other communities suffering violence that don’t denounce or report due to fear.

The attacks on Aldama and Nuevo San Gregorio seems to be a continuation of the federal government’s low-intensity war against the Zapatistas, now on steroids, an escalation rather than something completely new or different.

A Big Increase in Organized Crime

What has produced the most shocking/attention-grabbing headlines is the emergence of the “Motonetos” (Scooters) in San Cristóbal and the shootout in San Cristóbal’s Northern Market between local organized crime groups. We see a dramatic increase in the day-to-day distribution of drugs by local organized crime groups, including the former paramilitary groups, which are now narco-paramilitary groups, meaning those groups have even more money to buy high-powered weapons and other military equipment. Two recent reports help to detail and explain the increased violence due to organized crime: a statement from the Catholic Diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas and a report from the National Citizen Observatory.

Statement from the Diocese of San Cristóbal

On July 3, 2022, religious leaders of the San Cristóbal de Las Casas Catholic Diocese issued a statement denouncing a scenario of murder and other terrifying forms of violence, including the sale of organs, human trafficking for sexual and labor exploitation, as well as for pornography, all of this taking place within its jurisdiction, which includes most of the heavily indigenous eastern side of Chiapas, also considered the area of Zapatista influence.

The statement came just a few weeks after the shootout between armed groups fighting each other for control of San Cristóbal’s Northern Market, in which one person died after being struck by a ricocheting bullet. On June 14, masked men dressed in black with high-powered rifles blocked streets and fired shots into the air as terrified residents and shoppers in the area took cover wherever they could. One group was identified as the “Motonetos,” also known as “Scooters,” a group of young San Cristóbal residents who travel on motorcycles and work with organized crime.

The Diocese stated: “Every day organized crime occupies more space in Chiapas territory, painfully it’s adding to the national situation, and there is a struggle between competing groups at the state and local level.” This confirms the information San Cristóbal residents and NGO workers have given to solidarity folks visiting Chiapas from the United States: two national drug cartels are fighting for control of Chiapas and local organized crime groups have links to one or the other national cartels.

The Diocese recalls the murders of Simón Pedro Pérez López, a catechist and past president of Las Abejas of Acteal, and the indigenous prosecutor Gregorio Pérez in 2021. It also recalls several murders in 2022: the journalist Fredy López Arevalo, Señora Paula Ruíz and very recently the municipal president of Teopisca, a municipality adjacent to that of San Cristóbal.

The Diocese is, in part, motivated by recent arrests of its “pastoral agents.” It specifically refers to the May 31 arrest of Manuel Sántiz Cruz, a Tseltal defender of human rights and territory in the parish of San Juan Cancuc, and four more members of that parish. It further mentions the arrests of the councilor president of Pantelhó Municipality, Pedro Cortés López and municipal council member Diego Mendoza Cruz, with a luxury of violence.

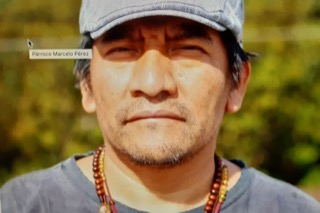

The straw that seems to have broken the camel’s back was the state attorney general’s request that a court issue an arrest warrant for Father Marcelo Pérez Pérez, currently a parish priest in San Cristóbal, but until very recently the parish priest in Simojovel municipality, next door to the conflictive municipality of Pantelhó. Father Marcelo served as a mediator after the El Machete Self-Defense group rose up and removed the municipal council, as well as a group of 21 alleged hit men (sicarios) for a former municipal president’s organized crime group referred to as “Los Herrera.” At that time, these acts appeared to have the support of a large majority of the population, and they supported Cortés López as the new municipal president.

Nineteen of the alleged hit men who El Machete removed from their homes on July 26, 2021 have not been heard from since; their whereabouts are unknown. Their relatives are demanding action and are represented by a lawyer. They are pressuring the State Congress and the press. Now, the state government blames Cortés López, Mendoza Cruz and Father Marcelo for their disappearance. A judge issued the arrest warrant for Father Marcelo the day after the Diocese issued its statement, perhaps a warning to the Diocese.

The National Citizen Observatory

The denunciation from the Diocese follows a June 8 report from the National Citizen Observatory that the presence of organized crime has skyrocketed in Chiapas. The report details the increase in complaints to state authorities about the crime of drug dealing. Complaints rose 400% in just one month. It adds that there are municipalities with a 2,000 % increase in the same time period (April 2022).

Pueblo Creyente, a people of faith organization affiliated with the Diocese of San Cristóbal, denounced that: “insecurity, violence and territorial disputes provoked by organized crime (…) bring very strong consequences for our municipalities and our peoples, such as narco-politics, drug addiction in the ejidos, the increase of bars, car and motorcycle theft and murders.”

A member of Pueblo Creyente denounced in a meeting that last April, when she was riding in a public transport van, “some armed men stopped us, they took the women out, not me, I believe because I am an elderly person. They took them away (three women), their families didn’t find them, we haven’t heard from them again, but there is fear of denouncing.”

A dramatic example of this struggle for control took place after the Diocese issued its statement. A violent two-day battle for territorial control took place in the border municipalities of La Trinitaria and Frontera Comalapa between two local organized crime groups working for national crime cartels. More than four thousand people had to leave their homes to avoid the gunfire. After several days, the Mexican Army was able to stop the gun battle, arrest 3 people and confiscate an arsenal of weapons.

There are other factors contributing to the violence and repression. Not all violence can be attributed specifically to the presence of national organized crime groups. However, the presence of two national cartels battling each other for control of the state dramatically increases the amount of violence, which creates fear.

to be continued… Stay tuned for Part 2

Published by the Chiapas Support Committee, an adherent to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, and a 501c.3 nonprofit in Oakland, California

The internal crisis of the empire

By: Raúl Zibechi

Reaffirming the idea that empires collapse from within, when their contradictions cause their decline or facilitate conquest by their enemies, we see how the United States Armed Forces are having enormous difficulties recruiting members.

The US media maintains that the Army confronts “the worst recruitment crisis since the end of the Vietnam War,” that is, since compulsory military service [the draft] was eliminated, according to a report from Politico in July.

With just two months to go in the fiscal year, the Army had reached just 66 per cent of of its recruitment goal. General Joseph Martin told the House Military Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives that the Army could lose more than 20, 000 members, down from 466,000 soldiers to just 445,000, due to the difficulty of finding recruits.

However, as the Tom Dispatch report points out, the force offers “enlistment bonuses of up to $50, 000 dollars” to the candidates who decide to join the ranks. The other forces also offer bonuses, but all face the same problem recruiting combatants, with the Air Force facing the greatest difficulty after the Army.

The reasons must be found in a broken society, in frayed institutions and in a nation with no other goal than to continue dominating the world.

Only 23 percent of the Americans between 17 and 24 years of age can be selected to enter the Armed Forces, compared to 29 percent in previous years, NBC News highlights. The rest, more than three-quarters of youth, are automatically disqualified for obesity, criminal history, drug use, and physical or psychological problems.

In the US, there is a real epidemic of obesity, which has shot up in recent years and is growing five times faster than before among children, killing 300 thousand people each year.

The suicide rate is the highest among rich countries (14 deaths per every 100 thousand inhabitants), twice that of the United Kingdom and is largely due to mental illness, making up what is called “deaths of despair,” which also encompasses deaths by drug overdose, international reports on health reveal. The US has the lowest life expectancy among the 38 countries that make up the OECD. [1]

Indeed, a report from the Commonwealth Fund reports that: “Americans are living shorter and less healthy lives because the health care system doesn’t function as well as it could. However, the US spends more on health care than any other OECD country (17 percent of GDP in 2018), because it’s wasted on private insurance, while public care is deficient.

Mental health is another big problem that affects one in five young women and one in 10 men under 25. These are typical effects of inequalities based on wealth and skin color, in a country where the concentration of income continues to grow and the Afro-descendent population is severely punished by repression and the lack of prospects.

There is an additional problem, inside the Armed Forces. Of the population eligible to become combatants, only 9 percent have any propensity to enlist, due to the risk of physical injury or death, the possibility of post-traumatic stress and other psychological disorders. In addition, 34 percent of young people answered a survey assuring that they didn’t like the military lifestyle and 28 percent pointed to the possibility of sexual harassment or assault, Politico explained.

Much more data could be added that attest to the decline of the empire, and now also the difficulty in sustaining its Armed Forces. This doesn’t mean that they are going to give up, far from it. It means that more and more private armies will be created, like the famous Blackwater, now renamed Academi, a private company of mercenaries.

The so-called “private armies” are in reality paramilitary organizations that reach beyond the State armies, but governments don’t pay the costs political costs of sending their soldiers. The British G4S Secure Solutions, for example, intervenes in 125 countries, has 620,000 employees, recruits serial criminals and has excelled in assassinations of personalities, among many other crimes (https://bit.ly/3clRuul).

All the data point in the same direction: the capitalism of death that oppresses us is in the phase of causing genocide out of the desperation caused by the systemic changes underway.

It’s up to the movements to decide what to do, as there are no trustworthy institutions when the known world collapses. When those above only think of themselves, we are the ones that must organize in order to survive.

[1] OECD – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, August 26, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/08/26/opinion/019a2poln and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

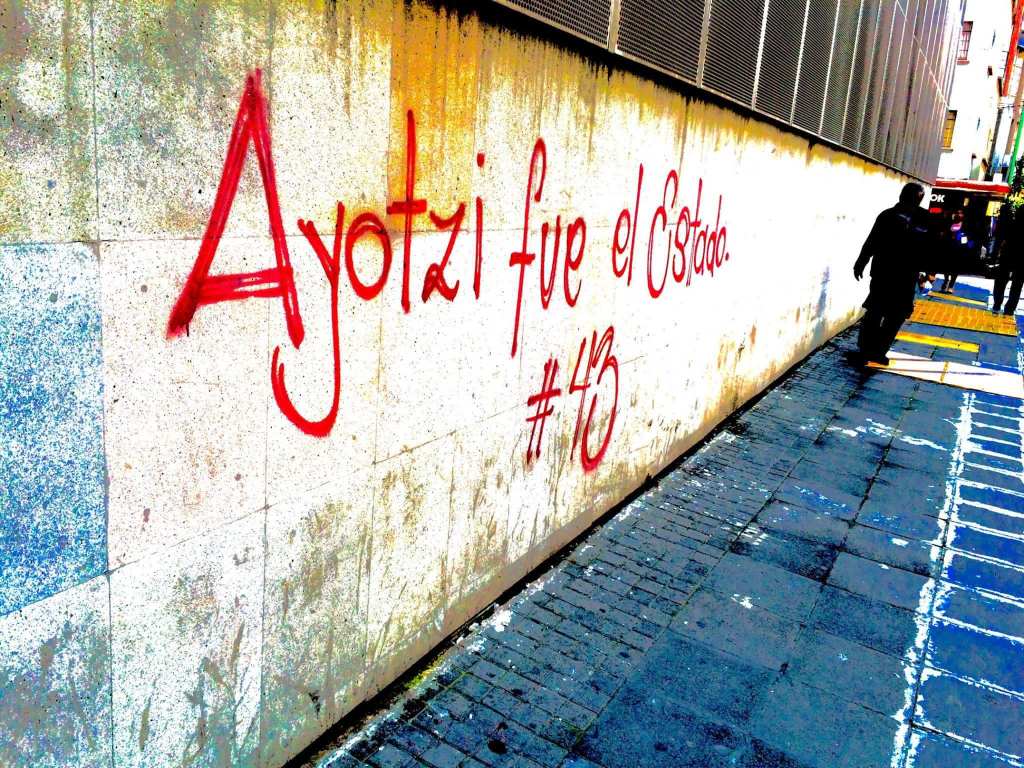

Ayotzinapa, on the edge of the abyss

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

Three events overlap in the Ayotzinapa Massacre. The central one is the savage aggression against students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College by organized crime, the military and police. The second one consists of the decision of state agents at different levels to not intervene to prevent the crime from being consummated, despite having real-time information about what was happening. Finally, we have the state maneuver of hiding the true dynamics of the extrajudicial executions and forced disappearances, and the fabrication of a version of the facts, obviously false.

El recent report of the Commission for Truth and Access to Justice for the Ayotzinapa case (https://bit.ly/3wmYqhP) has big and important gaps. It does not specify, for example, something as important as where the remains of the 40 disappeared students (three were already identified). Nor why those responsible for security did nothing to prevent the barbarity. Even less does it explain what led the federal government to invent the monstrosity of the “historical truth.” Its reading allows us to intuit many hypotheses, but these are not explicitly enunciated.

An additional bad sign is that the prosecution of Murillo Karam was not done by the Ayotzinapa case unit, but rather by the Seido. [1] The recrimination of prosecutors by the judge at the former prosecutor’s hearing, for “not being prepared” for the indictment procedure, is a terrible message. Nor does the GIEI’s statement look good, that “we didn’t know, nor have we directly accessed and examined the material from which the screenshots that appear starting on page 38 emerged. Nor have we accessed the expert reports carried out on them.”

In spite of this, it would seem that the report is a step forward in clarifying the facts and opening a door for judging and punishing those responsible for the massacre and its coverup. Admitting that we’r’e dealing with a State crime is a relevant event, whose medium-term consequences are unforeseeable.

It’s false that the report has no new information and that everything it points out was previously known. It’s even more of a lie that its content is the same as the “historical truth.” The only ones who are interested in spreading these rumors are those who elaborated, defended and benefited from the lies of the official Peña discourse.

One example among many. The “historical truth” concealed, against all available evidence and testimonies, the existence of the famous fifth bus, in which heroin or money was being transported. On the other hand, the new document confirms the movement of the EcoTer bus without being stopped, freeing 16 checkpoints on the perimeter of Iguala at all its exits. Who, if not the Army, was capable of facilitating an operation of that magnitude?

Beyond gaps and limitations, the document of the Truth Commission provides important data on the attack against the students and the government maneuver to obscure it.

But, in addition, where before there were loose pieces or a few assembled pieces, today there is a puzzle that, without being completely solved, groups its pieces with meaning. There is a narrative based on solid evidence, not extracted by torture, which seems to open the door to find out what happened and punish (some) culprits.

The report points out, over and over again, the responsibility of soldiers and sailors in the State crime. It confirms that military commanders in the region did not carry out, as they were obliged to do, actions for the protection and search for the soldier Julio César López Patolzin, one of those infiltrated by the Army among the students, in a clearly counterinsurgent action. Tracking him down could have helped to find some of the students alive. It’s not a saying. Four days after the night in Iguala, six students were alive, kidnapped in a warehouse in Pueblo Viejo (Old Town).

The document shows the presence of the narco-state in the region, and the role of the Army in it. “There was –the report points out– an evident collusion of agents of the Mexican State with the Guerreros Unidos criminal group that tolerated, permitted and participated in the acts of violence and disappearance of the students, as well as in the government’s attempt to deny the truth about the events.”

The Army knew in real time what happened and not only did nothing to prevent it, but many things could not have happened without their direct intervention. In a conversation between El Chino –visible leader of the criminal group– and a high-ranking military officer identified as El Coronel, the latter ordered that: “soldiers remove the remains from Iguala,” and added: “They took most of them to the battalion” (https://bit.ly/3AfWdpm).

Above all considerations, if anything made it possible for the “historical truth” to collapse, for the truth about the night in Iguala to begin to be known and a window would seem to be open for justice to appear, it is the heroic, selfless and unyielding struggle of the parents of the 43 Ayotzinapa students. Without their unyielding will to get to the bottom of the matter, without their tireless decision to find their children, without their wise distrust of official siren songs, without their determination to mobilize every day so that oblivion does not defeat memory, very little would have been achieved.

Beyond these initial reflections on the edge of the abyss, to evaluate the scope of the Truth Commission report in depth, it’s necessary to wait for the parents to announce their opinion on it. Their moral authority is indisputable. No one better than them to weigh in on the document’s genuine transcendence. This Thursday we will know it.

[1] Seido – the initials for the office of the Special Prosecutor for Investigation of Organized Crime.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, August 23, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/08/23/opinion/018a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

US, Mexico and the geopolitics of oil

By: Carlos Fazio

At the dawn of the 21st century, after the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, United States president George W. Bush and his advisers sought to sustain the declining global political power of the empire based in a powerful military apparatus, an economy and permanent war diplomacy and the perpetuation of a climate of chaotic instability centered on fear. Even then, the relative decline in US industrial capacity exhibited the erosion of imperial hegemony in the world. Nevertheless, the group of neoconservatives that surrounded Bush Jr. (Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Armitage, Perle et al.) dusted off the 1977 Project for the New American Century and The New York Times Magazine and The Wall Street Journal amplified the idea that a “certain dose of US imperialism” and “expansionism” could be the “best answer” to terrorism. As Michael Ignatieff pointed out at the time, the US war on terror was an “exercise in imperialism” (Times Magazine). The invasion of Afghanistan (2001) was followed by the failed coup d’état of the Pentagon and the CIA in Venezuela (2002) and the military invasion of Iraq (2003), both hydrocarbon-producing countries and members of OPEC. It repeated the old history started by the US in Iran in 1953, with the overthrow of Mossadegh, always with the lure of establishing “democracy.”

Beyond conspiracy theories (the interests of the Bush clan and the Vice President Dick Cheney in the oil industry), everything has to do with geopolitical concerns and hydrocarbons. In those days, M. Klare said in La Jornada that whoever “controls the Middle East will control the global oil tap” in the near future. Henry Kissinger had already said: “Control the oil and you will control the nations; control the food and you will control the people” (the current Davos agenda). Oil keeps the world’s armies and industrial infrastructure moving. For the U.S., access to the hydrocarbon was a matter of “national security.” Hence the attempts to overthrow Hugo Chavez and Saddam Hussein; for stabilizing or reforming the Saudi regime, and consolidating its position in Turkey and Uzbekistan to control the oil reserves of the Caspian basin. Objective: to turn off the “tap” to Europe, Japan and China.

In 2003, U.S. policy toward Iraq generated outbreaks of resistance from Germany, France, Japan, and China, and the blurred profiles of the Eurasian power bloc that Halford Mackinder had envisioned as a candidate for geopolitical dominance of the world, so feared by Kissinger, loomed. Hence, along with its military power (with its low-intensity wars, color revolutions and covert operations), sanctions (punishments) and economic-financial blockades and media terrorism, cultural imperialism became an important weapon to establish US hegemony through a variable combination of consent and coercion (including invasions and the elimination of enemies), in order to entrench Washington’s domination and intellectual and moral leadership.

Domination that had been imposed on Latin America in the previous two centuries under the protection of the Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny, through a combination of privileged trade relations, patronage, clientelism, covert coercion and coups d’état, and in its last stretch, via the financialization of the economy through the Washington Consensus (1989), as an exercise of power by the Wall Street-Treasury Department-IMF/World Bank/IDB complex, which, through the neoliberal State, promoted a series of megaprojects on a continental scale, which deepened what David Harvey has called “accumulation by dispossession,” a contemporary imitation of the primitive or original accumulation described by Marx in Capital, based on violence, plunder, fraud, usurpation and dispossession of the commons.

In 1992, with its sights set on the privatization of Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and the Federal Electricity Commission, the United States had achieved “negotiating ” the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico: the alliance between the shark and the sardine (which went into effect in 1994), in unison with the energy counter-reform of Carlos Salinas that opened the way to the alienation of gas, oil and mining resources from the subsoil.

During the presidency of Vicente Fox (2000-06), and along with the design of new economic corridors in the world (such as the Russia-Iran-India agreement to establish a shorter and cheaper Eurasian trade route through the Caspian Sea, instead of the Suez Canal), the US launched the Plan Puebla-Panama (PPP), as part of a de facto territorial reorganization project that sneakily introduced Mexico into the Alliance for North American Security and Prosperity (2005). The ASPAN included a cross-border energy integration (gas pipelines and laying of electricity networks from the US to the Panama Canal through Mexico) subordinated to Washington and megaprojects of transnational capital that subsumed the economic criteria to those of the security of the hegemonic power, with a supranational regulation that set aside legislative control in the partner and weakest link: Mexico. Meanwhile, counterinsurgency laws were imposed that criminalized protest and poverty and accentuated social discipline.

With Felipe Calderón (2006-12), the PPP mutated into the Mesoamerican Project, incorporating the “democratic security” of the Colombian autocrat Álvaro Uribe as part of the Merida Initiative, which with the help of the CIA, the DEA and the Pentagon militarized and para-militarized Mexico, and became special economic zones with Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-18). Today, under the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, US imperialism’s old nineteenth-century yearning to control the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, comes to life through an interoceanic corridor that will link Coatzacoalcos, in the Gulf of Mexico (Atlantic Ocean) with Salina Cruz, Oaxaca (Pacific Ocean), dynamically interrelated with two other megaprojects: the Maya Train in the Yucatan Peninsula and the Olmec refinery in Dos Bocas, Tabasco. All three, as new enclaves for the accumulation of capital by dispossession.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, July 25, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/07/25/opinion/019a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

They demand immediate attention to the superior interest of Zapatista children

By: Chiapas Paralelo

Members of the Latin American Network of Research and Reflection with Girls, Boys and Youth (REIR) demanded attention and immediate solution to the problem of land invasion of community lands in Nuevo Poblado San Gregorio since November 2019. The Network recalled the dispossession of close to 155 hectares belonging to EZLN support base families, land on which they plant and harvest their foods.

That’s why they considered the action severely harmful for the full exercise of the rights of Zapatista girls and boys, because it violates their superior right to live a dignified life, based on the fact that their access to food, health and education are totally or partially compromised at this time, due to the invasion of their territories.

“This situation, we insist, is extremely delicate, since it has been going on for almost three years, which has caused the breakdown of the social fabric in the daily life of the Zapatista families, and in the construction of their community life based on principles of autonomy,” they said.

The members expressed the obstruction of the political and peaceful process of Zapatista autonomies as a result of this event. In addition, they considered that there is a situation of threats, harassment and intimidation by this invading group, which adds to the failure of the Mexican State to guarantee human rights.

La REIR, with information from the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center, recalled the daily increase of violence in said region, since 21 aggressions against EZLN families have taken place so far this year. Violence has been manifested in the following ways: intimidation, death threats, sexual violence and torture; physical aggressions, theft of cattle and destruction of property; water cut-offs, vigilance; blocking, control and charging for free transit, as well as kidnapping people.

Finally, they demanded justice, attention, mediation and an urgent solution to the conflict on the part of the State, safeguarding the integrity of all the families, and immediately attending to the superior interest of boys and girls.

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Monday, July 18, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/07/exigen-atencion-inmediata-al-interes-superior-de-la-ninez-zapatista/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

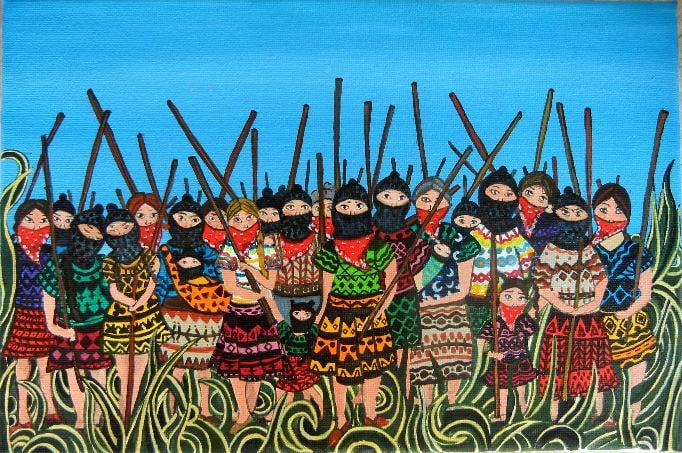

19 years of the caracoles and the good government juntas

By: Gilberto López y Rivas

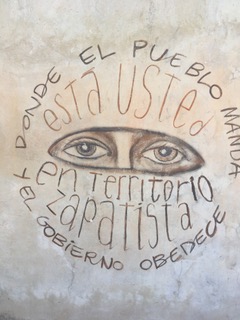

On August 9, we commemorated the 19th anniversary of the creation of the caracoles and the good government juntas (JBG, their initials in Spanish), which replaced the Aguascalientes and their authorities, and that constitute regional or zonal forms of self-government of peoples (Tseltales, Tojolabales, Mames, Tsotsiles, Choles and Zoques), communities and municipalities that are grouped around the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional). In 2019, the EZLN reported on the creation of another seven caracoles, in addition to the five already existing, and four new Zapatista rebel autonomous municipalities (also known as MAREZ, their Spanish acronym), to form a total of 43 bodies of self-government starting from the principle of mandar obedeciendo (govern obeying), in what was considered by Subcomandante Moisés, as breaking the counterinsurgent siege and the defeat of its strategy of patronage co-optation, imposed by the successive governments. Thus, the seats of these caracoles were installed within territories of official municipalities: four in Ocosingo, Amatenango del Valle, Tila and San Cristóbal de las Casas, while the five original ones are in La Realidad (Border Jungle, Morelia (Tsots Choj), La Garrucha (Tseltal Jungle), Roberto Barrios (Northern Chiapas) and Oventic (Chiapas Highlands).

Conceptualizing the autonomic process of the Zapatista Mayas as advanced forms of anti-systemic resistance, during these 19 years the transformation of social subjects in multiple directions has deepened in the caracoles, one of the most important being their struggle against patriarchy, and for changing gender relationships, which began in the clandestine years, and was expressed in the Women’s Revolutionary Law, which in March 1993 signified the “first uprising” before 1994, within the guerrilla organization, according to the story of then Subcomandante Marcos.

The meetings of thousands of women from dozens of countries, convened by the EZLN in rebel territory, such as the one in 2019, have been important platforms in the fight to stop violence against women and femicides, and to deploy a feminism with community roots of historical scope and depths.

Pablo González Casanova in his essay “The Zapatista caracoles: networks of resistance and autonomy” points out that: “The idea of creating organizations that are tools of objectives and values to be achieved and making sure that autonomy and ‘govern obeying,’ do not remain in the world of abstract concepts or incoherent words is one of the most important contributions of the caracoles. “

Certainly, this readjustment and strengthening of the autonomous governments at their three levels, during these 19 years, have allowed the consolidation of political, economic, social, cultural, educational, justice and health structures, with their corresponding infrastructures, in a multicultural and multilingual network that has not only achieved a participatory democratic regionalization of the communities and peoples that make up the EZLN, but, from a policy of brotherhood and conciliation (exercise of hegemony), they have been winning over broad sectors of the “party members,” as evidenced by the exponential increase in “govern obeying” in Chiapas territory. This qualitative development of the autonomies, in turn, makes the Zapatista project more sustainable in the face of counterinsurgency-paramilitary harassment, making the hypothesis of the Latautonomy project network more valid, and its emancipatory significance: “The sustainability of an autonomous system depends on its ability to link the level of local communities with a regional structure in a horizontal and interactive way. Through integration from below, participatory political-economic structures must be created that are articulated both within multicultural autonomies and outward, generating a project of alternative society.” (Leo Gabriel and Gilberto López y Rivas, coordinators. The autonomic universe. Proposal for a new democracy. Plaza and Valdés, Mexico, 2008, p. 28).

The harmonious coexistence of peoples, which over the years has created its own cultural identity – Zapatista Maya – which has managed to overcome the inter-ethnic conflicts so frequent in other latitudes, proves the veracity of the hypothesis of cultural cohesion, which proposes: “The greater the degree of cultural identity, the greater the effectiveness of an autonomous system” (ditto, p. 36). Likewise, the governance hypothesis, which states that: “The more efficient the conflict resolution mechanisms applying customary law at the local and regional level, the greater the political sustainability of the system” (p. 48), has been patented in these 19 years of existence of caracoles.

Congratulations, EZLN. Another world is possible!

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, August 19, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/08/19/opinion/018a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Ejido Candelaria reiterates its demand for the right to self-determination and autonomy

BY: Yessica Morales

Communities from the municipalities of Salto de Agua, Palenque, Yajalón, Sitalá, Chilón, Altamirano, Ocosingo, Oxchuc, Tenejapa, Cancúc, Huixtán, Chicomuselo and the Candelaria Ejido of San Cristóbal de Las Casas municipality have demanded respect for their forms of self-government from the Mexican State, under cover of the Movement in Defense of Life andTerritory (Modevite).

The Tsotsil community of the Ejido Candelaria belonging to San Cristóbal de Las Casas municipality, in collaboration with academic institutions [1], held a press conference last August 12, to communicate the consensus agreement to carry out political and legal actions for the recognition of their community government, as an exercise of the right to self-determination and autonomy.

The foregoing, before the authorities of all levels and government bodies, therefore the authorities present at the event [2] had the task of publicizing and disseminating what they have requested from the Municipal Council of San Cristóbal de Las Casas and the State Congress of Chiapas.

First, they indicated that the Ejido Candelaria is a Tsotsil community, it has its own community system, for that reason they decided to follow the example of communities in the state of Michoacán, who claim the right to indigenous self-government.

In that sense, they claimed from the Municipal Council the right to administer the proportional part of the budget that corresponds to the Ejido. Likewise, they demanded that the State Congress recognize their community government as indigenous peoples.

Thus, they demanded respect for their rights as established in Article 2 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States, Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

They declare that States must recognize and guarantee the self-determination, autonomy and self-government of indigenous peoples and communities, and allow them to preserve their institutions and customs, as well as respect for and recognition of their own normative systems in order to freely determine their political status, means of subsistence and development of forms of social, economic and cultural organization, added the community authorities.

Of equal importance, they pointed out that on January 4, 2022 the Ejido presented the formal request to the State Congress to recognize and guarantee the rights to self-determination, autonomy and self-government. They also submitted the request to the Municipal Council of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, to transfer the proportional part of the public resources that corresponds to them, and that the community government administer them.

However, they denounced publicly that both requestswere denied, despite have full support in the laws of the country and international conventions. Given this, they decided to go to the Federal Judiciary to request an amparo in the recognition of their rights.

We demand that the competent authorities respond to our requests, fully respecting the rights that correspond to us as indigenous peoples. La Candelaria Ejido has the legal backing of the constitutional reform of 2001 and international treaties such as ILO Convention 169, which oblige states to recognize and guarantee the self-determination, autonomy and self-government of indigenous peoples and communities,” the authorities said.

Consequently, they invited the communities of indigenous peoples to get organized to constitute their own self-government bodies,because community organization is an expression of another democracy.

In addition, they affirmed that if the federal, state and municipal authorities are not able to respond to their needs, it is their right to embark on the path of life, solidarity, peace and respect, for the beings who inhabit Mother Earth, where the men and women who fought before also live.

For her part, Juana Hernández Díaz, representative spokesperson for the women, said that the community has approximately 4 thousand inhabitants. An organized community, with authorities such as: ejido commissioner, surveillance council, rural agent, rural judge, education committee, health committee, water board, road board, celebration board and their members.

We come to demand our rights as indigenous peoples, as the law states. Article 2, which recognizes and guarantees the right of indigenous peoples and communities to self-determination, states that the Mexican nation is unique and indivisible, establishes that the nation has a multicultural composition originally based on its indigenous peoples, the spokeswoman said.

Hernández Díaz emphasized that the community is forgotten by the municipality of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. In other words, the community depends only on its people; if the streets have pot holes it’s the people and the community authorities who fix them, taking money from their own pockets, and that isn’t fair.

Because as an indigenous community, we have rights that the budgets give us to fix what our community needs, that’s why we have come to ask that our rights as indigenous peoples be respected, taking into account the needs of our community. We want the budget for our community handed over to us and not through intermediaries, the spokeswoman indicated.

[1] Academic institutions:

Observatorio de las Democracias: sur de México y Centroamérica del Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica – Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas (CESMECA-UNICACH).

Universidad Iberoamericana a través de la Clínica Jurídica Minerva Calderón.Observatorio de Participación Social y Calidad Democrática.

[2] Principal Authorities of the Candelaria Ejido:

Juan Gómez Díaz, comisariado ejidal de la comunidad

Agustín Díaz Ruiz, secretario del Consejo de Vigilancia

Salvador Díaz Pérez, juez rural municipal

Manuel Hernández Gómez, presidente del Consejo de Vigilancia

Fernando Gómez López, agente rural municipal

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Sunday, August 14, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/08/ejido-candelaria-reitera-exigencia-por-el-derecho-a-la-libre-determinacion-y-autonomia/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

To govern by obeying: 19 years of the caracoles

By: Raúl Romero*

August 9, 2022 was the 19th anniversary of the creation of the Caracoles and the Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Good Government Juntas), a watershed in the history of the Zapatista movement and a process that has become a reference for emancipatory projects in different parts of the world. The history is complex, long and, to be precise, it is rather a meeting of multiple histories in which the Zapatista Mayas are the protagonists and architects and of their own present and future. Tracing those stories that today have led to the vindication of autonomy would imply reviewing diverse resistances of indigenous peoples in Mexico, but also of other liberation movements, some of them reclaimed in the First Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle.

The Zapatistas themselves have told the stories of the caracoles and their Good Government Juntas. In the text Chiapas: The Thirteenth Stele, published in seven parts in July 2003, they explained the rationale, took stock of what had been achieved, and of the difficulties up to that point. In the case of the Good Government Juntas, the history goes back to December 1994, when the Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ) and their autonomous councils were created, an exercise of indigenous autonomy, led by the communities themselves, and in which the EZLN has dedicated itself only to accompanying and intervening when there are conflicts or deviations.

In rebel territory, no position of authority is paid; it is conceived as a task for the benefit of the collective, and it is rotating. The community helps with their upkeep, and also sanctions or removes authorities who do not fulfill their duties. Only civilians can hold positions of authority, either in the community or in the autonomous municipalities. These autonomous councils are the ones in charge of creating the material conditions for resistance, those that are charged with governing a territory in rebellion, without any institutional support. The achievements since then are impressive in many areas: health, education, justice, communication, gender, work, housing, land, commerce, food, culture….

However, the Zapatistas identified problems such as the imbalance in the development of autonomous municipalities and communities, problems between autonomous municipalities and between these and governmental municipalities, complaints of human rights violations, and others. Thus, in order to face the problems of autonomy and to build a more direct bridge between the communities and the world, Good Government Juntas were created, which also ensures governing by obeying. The juntas are composed of two or more delegates from each of the autonomous councils of the municipalities in each zone and have their headquarters in the caracoles.

The caracoles also have a history of their own. In August 1994, in order to hold the National Democratic Convention in Guadalupe Tepeyac, in Zapatista Chiapas, the rebel peoples built an Aguascalientes, a space for dialogue and encounter between the Zapatistas and national and international civil society. On February 9, 1995, this Aguascalientes was destroyed by the federal army under the command of Ernesto Zedillo. But, determined to build and share the projects for life between their territories and world, the Maya rebels set about the task of constructing five other Aguascalientes, this time in Oventic, La Realidad, La Garrucha, Roberto Barrios and Morelia.

In August 2003, the Zapatistas also decided that the Aguascalientes should perish, and put an end to the paternalism of some NGOs that sought to impose projects and reduce solidarity to projects of pity and charity. But the five Aguascalientes died to give life to something new: five caracoles, doors by which “to enter the communities and for the communities to go out; like windows to see us inside and for us to see outside; like speakers to take our word far away, and to listen to the word of those who are far away. But above all, to remind us that we must watch over and be attentive to the fullness of the worlds that populate the world.

To document the advances and achievements of the caracoles and the Good Government Juntas, one can review the Notebooks from the Zapatista Escuelita or Volume one of Critical Thought Versus the Capitalist Hydra, because the Zapatistas also have this characteristic of accompanying their practice with their own theory. You can also review great works such as Paulina Fernandez, Zapatista Autonomous Justice. Tzeltal Jungle Zone.

In 2019 the Zapatistas announced that, as part of the Samir Flores Vive campaign, they had reorganized and expanded their territories. They now have 12 caracoles and their respective Good Governance Juntas. We are witnessing an exercise of political imagination, of creative resistance, of autonomy, of governing by obeying. A process that is not exempt from contradictions, but that does not stop betting on the construction of an alternative beyond capitalism. Long live the caracoles.

*Sociólogo. @RaulRomero_mx

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, August 15, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/08/15/opinion/020a1pol, Translated by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

Movements in the post-pandemic

By: Raúl Zibechi

They toured the continent for months: Mexico, Colombia, Rio de Janeiro, Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina. In all of them, similar situations are directly observed, which are added to the data that are arriving through other channels. Broadly speaking: disarticulation and degradation of social relations; state, para-state and narco-violence; great difficulty for movements and peoples to construct.

Perhaps this breaking is the way the systemic storm is presented to us, compounded by climate chaos and the collapse of nation-states. It’s not easy to establish a comprehensive narrative, but there are common situations beyond the differences between geographies.

The reasons why our societies are breaking up are diverse, encompassing both the material and the spiritual.

Poverty grows permanently and constantly, a consequence of the voracity of the most concentrated capital that leads the population to unsustainable living situations. Meanwhile, governments only manage poverty with social policies that seek to tame the popular classes and indigenous and black peoples.

The accumulation by dispossession/fourth world war against the peoples is part of this impoverishing model but, above all, it helps to explain the violence, the forced displacements, the theft of lands and the occupation of territories by the armed gangs that, by doing violence to peoples, favor the plans of capital.

Drug trafficking is one of the forms that the collapse of the system assumes, but we must be clear that it is used by the powerful against any organized movement, as the experiences of Colombia and Mexico teach. Drug trafficking was not directly created by capital and the states, but once it emerged, they have learned to direct it against our organizations.

The progressive governments that managed all the countries I am visiting and now do so in Colombia, accelerated the decline by deepening extractivism but, at the same time, by disorganizing the movements. They did this in a double way: appropriating the discourse and its ways of doing things, while launching armed gangs against the very peoples and social sectors that they intend to soften with social policies.

Both policies are complementary and are intended to facilitate the entry of speculative capital into the territories of the peoples, to convert life into merchandise.

The decomposition phase of our societies, links between below and entire peoples, is entering an acute phase by impacting even rural communities that previously seemed almost immune to these destructive and violent modes of capital and states, which work side by side to meet those goals. We are facing structural and systemic characteristics of capitalism, not specific deviations.

To the extent that we are facing relatively recent processes, the peoples and social sectors have not yet found ways to stop and reverse the destruction. At this point some considerations.

The first is to note the gravity of the situation, the high degree of decomposition not only of the organizations, but of the social bases in which they are referenced and rooted. Because the panorama can be summed up this way in almost all regions: societies and communities in decay and organizations threatened or co-opted by the system. Both facts are enormously destructive.

The reflection on the ways to remain what we are: peoples and social sectors that resist and build. The EZLN has adopted peaceful civil resistance to confront the armed gangs and to continue building the new world. It is a very difficult path, which requires will and discipline, perseverance and ability to face violence and crimes without falling into individualistic attitudes.

I believe that the ways adopted by Zapatismo, undoubtedly consulted and decided by the support bases, can serve as a reference throughout Latin America, because we face similar problems and because we must draw conclusions from the wars decided by the vanguards, which cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of people from the native peoples, blacks, campesinos and popular sectors.

Not repeating errors is wisdom. In various interventions, the EZLN has placed as examples the wars in Guatemala and El Salvador. In them, and this is my own [opinion], the attitude of the vanguards did not benefit the peoples, who paid for decisions they had not made with thousands of dead, and then entered into “peace processes” without consulting them, but saving the interests of the leaders and cadres.

I understand that those of us below owe ourselves, in these difficult moments, an in-depth debate on the ways of confronting the war from above. Without giving up or selling out, but taking paths that allow us to avoid war and to continue constructing without falling into provocations.

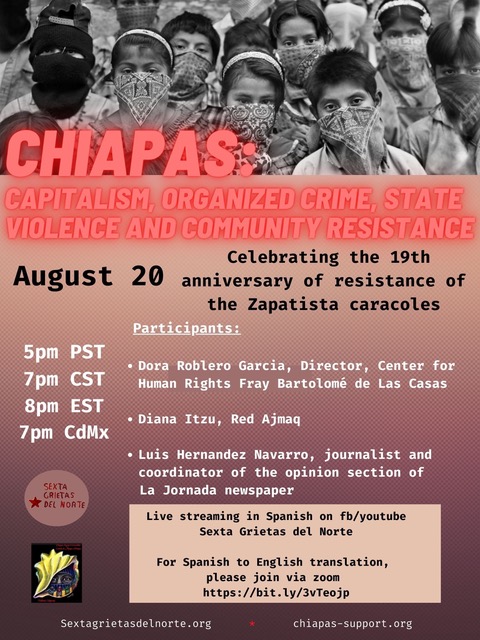

For details and links to the Saturday discussion in the above flyer: https://chiapas-support.org/2022/08/12/chiapas-capitalism-organized-crime-state-violence-and-community-resistance/

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, August 12, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/08/12/opinion/016a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

From the struggle for land to the caracoles

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

“Those who are not afraid, come forward to sign,” said then President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, mimicking the words of Emiliano Zapata, to 268 rural leaders, among them relatives of the Caudillo del Sur (the Caudillo of the South). At Los Pinos, in front of a picture of the head of the Liberating Army (Zapata), the leaders of the national associations went one by one to sign the Campesino Manifesto, which endorsed the end of agrarian redistribution and privatization of the ejido (communal land). The date is recorded alongside the ambush at the Hacienda de Chinameca: December 1, 1991.

Before the ceremony began, some of the representatives who caught a whiff of the trap, asked where the bathroom was and hurried away to avoid signing the document. Among them Pancho, a Tseltal leader who spent years fighting for land with his comrades from the Lacandón Jungle. He returned to his region and did not reappear in public life until long after the Zapatista uprising.

The leaders’ pledge to “surpass” agrarian redistribution by calling for a great commitment among the men of the countryside that day was seen as a great betrayal by hundreds of thousands of peasants throughout the countryside, but especially by the Chiapanecans, who had spent years struggling for their land. This counter-reform to Article 27 of the Constitution clouded the indigenous horizon, and motivated hundreds of communities to take up arms.

In the book Voices of History, the inhabitants of Nuevo San Juan Chamula, Nuevo Huixtán, and Nuevo Matzan recall their experience and that of their grandparents on the plantations and in the towns, where they were born and raised enduring hunger, as well as the reasons that led them to colonize the Jungle, seeking somewhere to eat a bit better and leave behind the pain of poverty and pure suffering.

Almost everyone we know goes out to the plantation. The landowners have become rich from our work, although we continue to live in poverty. In addition to all the hard work, we have more hardship there. The boss doesn’t care about the workers. We went hungry. The overseers mistreated us a lot: they beat us, they hit us with branches, with belts, with the palm of a machete, they kicked us; they punished us for anything, they explained. That is why, in a modern exodus, they left to seek a new life in the jungle.

The struggle for land became widespread throughout Chiapas during the 70’s and 80’s. Indigenous people were not only seeking to recover what the landowners had taken through violent dispossession; they settled the jungle to flee from misery. Then, a presidential decree from Luis Echeverría Álvarez in 1971 granted possession of 614 thousand hectares to 66 Lacandón families, thereby denying it to the rest of the settlers. In the words of the Union of Unions, behind the decree were the interests of National Finance, that is, the great bourgeoisie who wanted to take out all of the mahogany and cedar in the thousands of hectares titled in favor of the Lacandón Community.

The government wanted to reconcentrate the other indigenous peoples (Tseltales, Tsotsiles, Choles) and set the limits of the Lacandón Community, by means of the Brecha (“the gap”). The communities resisted by putting their bodies on the line with the slogan “No to the Brecha! In October 1981, 2,000 peasants from the jungle marched and occupied the Tuxtla Gutierrez Plaza. They walked for days to arrive at a vehicle that would take them to the state capitol. Years later, their struggle bore fruit. In 1989, Salinas de Gortari granted land to 26 communities.

In an interview with Roberto Garduño at La Jornada, the elder Sergio, the Representative (of the community), recalled those operations and how the inhabitants of the region were threatened by the authorities: “With the 1972 decree, the government began to say that we were going to leave by hook or by crook… but we didn’t want to leave because our parents and grandparents sought this place to live and work.

In the jungle, the rebels learned to handle a rifle to defend themselves against the white guards. Next came political and ideological education and the strengthening of communal organization. Sergio recalled the case of coffee sales as a symptom of injustice, because the coyotes cheat and pay ridiculous prices for the product.

“The Zapatistas,” he added, “began to work in our communities house by house and neighborhood by neighborhood. For a long time, we struggled peacefully, but they ignored us, that’s why we began… but they didn’t let us, they repressed us, that’s why we took up arms.”

Despite the fact that the white flag had been raised in the countryside, the 1994 uprising allowed campesinos and indigenous people, both Zapatista and non-Zapatista, to recover thousands of hectares. Instead of parceling them off, as others did, the rebels promoted collective organization projects for agricultural and livestock production, which have allowed them to control their lives and practice self-government. These experiences are the material basis on which the Caracoles are built, which this August 9 celebrated their 19th anniversary.

Carlos Salinas’ offense against the small rural producers — when in Los Pinos he called on the leaders to sign without hesitation an agreement to close the door on the campesino way of development–was answered years later by the EZLN, derailing in practice that end to agrarian land redistribution.

But the rejection went even further. From that initial “no!”, the rebels went on to build a society that represents the opposite of what Salinas wanted to promote. This alternative society has taken shape in the Caracoles. In them is the synthesis of both the deep and underground history of indigenous and campesino peoples for land and autonomy, as well as their willingness and power to build another world.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, August 9, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/08/09/opinion/016a1pol English translation: Schools for Chiapas, and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee