Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Argentina: the real face of the right

A La Jornada Editorial

An Argentine court sentenced Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner to six years in prison and disqualified her “in perpetuity” from holding public office in a case of defrauding the State for the alleged irregular award of 51 road works carried out in the province of Santa Cruz between 2003 and 2015, when Fernández was first lady (2003-2007) and president (2007-2015), A ruling that will surely be appealed and whose final outcome may take years.

In the immediate term, the political motivations and procedural cleanliness of the sentence are rude and unconcealable. From the outset, the so-called “road cause” violates the principle of not judging the same crime twice, since in 2015 it was prosecuted and dismissed by the same judge who years later, with the arrival of the ultra-neoliberal Mauricio Macri to power (2015-2019), decided to reopen it. In addition, as the defendant has pointed out for years, the prosecution did not present a single piece of evidence linking it to the contracts in question, and it cannot even be attributed administrative responsibility in the awarding of the works, since legally this falls not on the head of the Executive, but on his chief of staff. Regarding the approval of the budget, it is the power of Congress.

To the grotesque distortions of justice in this particular case are added the well-known right-wing political leanings of the Argentine Judiciary, the inability of a large part of its representatives to separate their ideologies and group interests from their judicial work and the absolute lack of dissimulation with which they operate in favor of de facto powers and characters of Macrismo.

Just in October, a meeting of judges, prosecutors (some of them involved in the trial against Cristina Fernández) and officials of the Macri government of Buenos Aires was unveiled at the estate of a British billionaire in the tourist mecca of Bariloche. This revelation was shamefully silenced by the mass media, whose maximum exponent, Grupo Clarín, is the greatest promoter of lynching against Kirchnerism since almost two decades ago, this movement tried to end the neoliberal looting that plunged the country into the greatest crisis in its history.

For all these reasons, Cristina Fernández refers to the corrupt structure of courts and prosecutors’ offices as a “judicial party,” that is, “a parastatal system that decides on the whole of Argentines outside the electoral results.” The mechanism to which the Peronist leader alludes, lawfare (use of judicial and legislative machinations to depose leaders uncomfortable to the interests of the oligarchies), has become the contemporary substitute for the coup d’états perpetrated by the right in the last century. It has already caused the illegal expulsion of Fernando Lugo in Paraguay and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, and is now being applied more and more aggressively to bring down Pedro Castillo in Peru. In Mexico there is a double precedent of the attempt to remove the immunity of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2005 and the judicial validation of the electoral fraud committed to impose Felipe Calderón in the Presidency in 2006.

Although the conviction against Fernández de Kirchner can be challenged and the process is expected to take years, the sentence issued yesterday constitutes irrefutable confirmation that the Argentine oligarchy has no ethical or legal scruples in the effort to impose its interests, and is willing to derail transformation projects by any means, however moderate. A trait it shares with the right wing in much of the world.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Wednesday, December 7, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/07/opinion/002a1edi and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Ricardo Flores Magón: Living Thought

By: Raúl Romero

In his history classes, professor emeritus at the UNAM Juan Brom used to say that it was a credit to the student movement of 1999-2000 that they named the main auditorium of the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences after Ricardo Flores Magón. The gesture was not minor and Brom knew it: it was not merely a homage from a generation that defended free education to the most important anarchist intellectual of the Mexican Revolution; it was, at the same time, a reappropriation of space, a plebian resignification, a rupture with the hegemonic history, and also perhaps, a sign of the advance of libertarian thought and action among social movements.

The first time Ricardo Flores Magón was taken to jail he was only 19 years old. At that time, the anarchist had moved with his family from his native Oaxaca to Mexico City and was studying at the National School of Jurisprudence. It was the spring of 1892, and people were moving, agitated, as if with the arrival of the season the outdated organism of Mexican society had been shaken, he would write in Apuntes para la Historia (Notes for History). My first prison. Ricardo Flores Magón described the anti-reelection movement against Porfirio Díaz, in which the student movement played a key role: At that time, we students were the idols of the people. The fact is that Ricardo Flores Magón and his brother Jesús, along with dozens of members of the student movement were arrested for participating in the protests. Fortunately, the massive popular mobilizations that followed their arrest saved them from being shot, as happened to so many others at that time.

The theoretical and practical contributions of the Magón brothers, and of other members of the Mexican Liberal Party (PLM), such as Práxedis Guerrero or Librado Rivera, have been widely studied from different standpoints. Particularly noteworthy is the link between the native communities and Magonism, a link that would not only be marked by the birthplace of Flores Magón, San Antonio Eloxochitlán, Oaxaca, populated mainly by Mazatec communities, but that would develop in the very formation of the PLM itself, as Benjamín Maldonado has pointed out in his text El Indio y lo Indio en el Movimiento Magonista (The Indian in the Magonista movement). On the nuances and debates of this link, it is worth reviewing the interesting conversation Ricardo Flores Magón and the national indigenous movement, recently held at the Institute of Social Research of the UNAM (https://bit.ly/3EolUGm).

Although the anarchism of the group led by Ricardo Flores Magón has had a profound impact on the political, cultural and intellectual life of Mexico, it should also be noted that from the beginning, and due to the very characteristics and conditions in which it developed, it was a transnational movement, with repercussions even beyond Mexico and the United States.

It is also among the youth movements where “Magonismo” has flourished with the greatest vigor. This libertarianism has taken root where anti-authoritarian, counter-cultural and anti-statist positions converge. Since the 1970s, whether promoting newspapers, magazines, libraries, radio stations, cooperatives, in the countryside and in the city, dozens of organizations and collectives have reproduced and nurtured Magón’s ideology in the struggle against the State and capital. In the 1990s, with the outbreak of the Zapatista rebellion and its frontal critique of the State, anarchist ideals also gained ground among hundreds of young people who wanted to build emancipatory alternatives against and beyond the State.

In September 1911 the PLM would launch a decisive manifesto: The storm is intensifying day by day: Maderistas, Vazquistas, Reyistas, Cientificos, delabarristas [1] call out to you, Mexicans, to leap to defend their faded banners, protectors of the privileges of the capitalist class. Do not listen to the sweet songs of those sirens, who want to take advantage of your sacrifice to establish a government, that is, a new dog to protect the interests of the rich. Up with all of you; but to carry out the expropriation of the goods held by the rich! The document would conclude with the slogan “Land and Liberty,” which Emiliano Zapata and the Liberation Army of the South would later make their own.

Almost a century later, the link between Zapatismo and Magonismo would be claimed by the EZLN, when the neo-Zapatistas named one of the autonomous rebel municipalities on land recuperated in 1994 as the Ricardo Flores Magón autonomous rebel municipality, located in the Tseltal zone of the Lacandón Jungle, near the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve.

One hundred years after his death, the thoughts and actions of Ricardo Flores Magón live on with those who struggle from below, against and beyond the State.

* Sociologist

Note:

[1] Those referred to are: Francisco Madera, Emilio Vazquez Gómez, Bernardo Reyes, the Científicos (scientists) and Francisco León de la Barra

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Sunday, November 20, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/11/20/opinion/015a2pol with English interpretation by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

They demand the freedom of 15 women prisoners in the San Cristóbal prison

Throughout Mexico, women are protesting violence against women and patriarchy with marches and other actions. This protest is relevant to Chiapas.

By: Isaín Mandujano

The Cereza Collective, a civilian organization for the legal support of women in Chiapas, today demanded the freedom of 15 women prisoners in the San Cristóbal de Las Casas state prison, who they said faced trials plagued with irregularities, such as the fabrication of crimes and some of them lacked translators at the time of their trial.

Patricia Aracil and a group of women activists and lawyers who form the Cereza Collective announced the names of 15 women secluded in state prison Number 5 in San Cristóbal de Las Casas municipality, who have clearly faced processes that show they were “victims of a sexist and patriarchal judicial process.”

In the framework of the activities of the International Day of Elimination of Violence against Women that is claimed on November 25 of every year, this Wednesday the Collective spoke out about 15 women prisoners.

Aracil and her compañeras who have visited that prison since some years ago, pointed out that each and every one of these women, have suffered violence from impoverishment, inequality, discrimination, racism, mistreatment and torture by their partner, followed by a violent arrest, the majority accused of crimes they have not committed or that derived from having to make economic decisions to sustain their children.

They are women who were involved forcibly by their partner, often even with threats and brutal violence that places them in a physical and emotional state of impossibility of escaping that situation with an insurmountable fear.

“Because in addition, it is their and their children’s lives that are at real risk. This also happens many times in the prosecutor’s office, forcing them to sign self-incriminating statements,” said the activist.

She said that these women have had to face a critical situation of femicidal violence and that in order to survive they have had to face that situation with very low possibility, they were able to save their lives in self-defense, because it is very difficult to defend themselves in that unequal battle against sustained violence and get out alive.

“A violence that local authorities still consider intimate family matters where we should not get involved, where the voice of women, when they can escape momentarily and ask for help from neighbors, authorities and institutions, is questioned and blamed,” she said.

She said that in Chiapas, judges continue to issue arrest warrants irresponsibly, continue to judge with a lack of gender, intercultural and human rights perspectives, continue to give convictions “as a rule” in the first instance, because it seems to be a pact with the prosecution, making up not only for the lack of adequate investigation, but becoming accomplices of the violence and human rights violations against women committed by prosecutors to incriminate them.

She explained that there is no justice for women in Chiapas. Therefore, she demanded that the State’s Judicial Power review the women’s cases and give them freedom.

“We demand that it be investigated and judged with a gender, intercultural and human rights perspective. We demand that the FGE stop constructing crimes against women, stop torturing and obstructing investigations. We demand the right to truth and justice, to transformative justice,” Aracil said.

She said that after reviewing each of these cases, she concluded that: “all of them are innocent and have experienced femicidal violence, mistreatment, inhuman treatment or torture in detention and in the prosecutor’s office.”

“It is necessary to combat corruption and impunity in the Attorney General’s Office, as well as the fabrication of crimes and acts of torture against women, a change in the justice system towards the human rights of women, girls and indigenous peoples is necessary,” said the lawyer.

She added that in addition, “judicial independence is fundamental for access to justice in Chiapas, the “norm” of conviction, contrary to the right to justice, must be eliminated.”

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Wednesday, November 23, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/11/exigen-libertad-de-15-mujeres-presas-en-el-penal-de-san-cristobal-de-las-casas/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

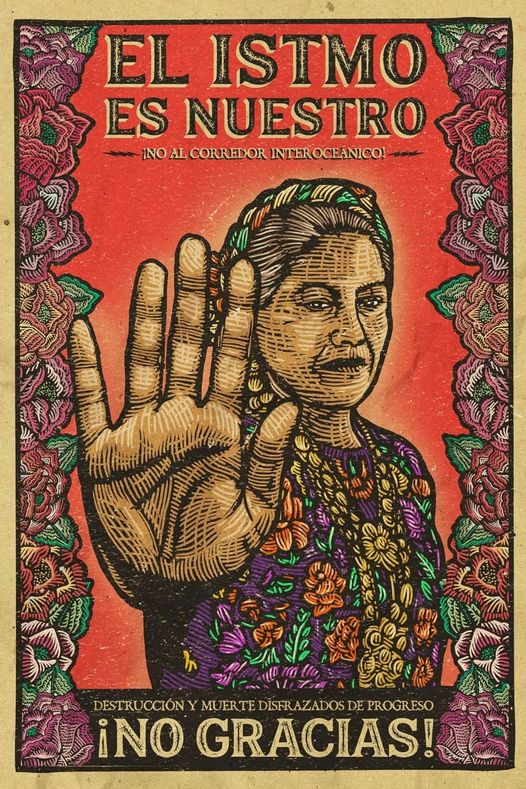

The Interoceanic Corridor and the National Popular Interest

By: Gilberto López y Rivas

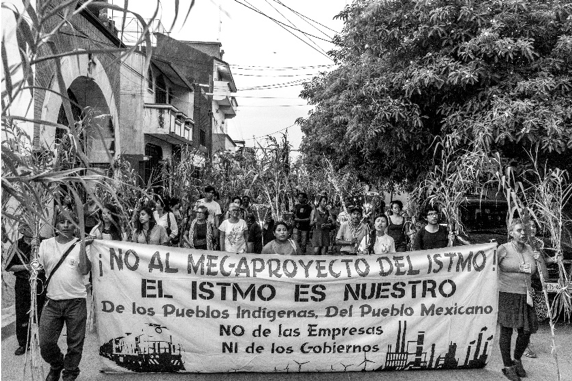

The recycled mega-project of the Tehuantepec Interoceanic Corridor –whose origins lie in the regional development program of the Ernesto Zedillo government, and whose distant origins lie in the damaging McLane-Ocampo Treaty (1859)– continues its slow but relentless advance, despite the opposition and resistance of multiple local, regional, national and international organizations and collectives that have exposed the serious damage that this monstrous project will cause to the environment, to the peoples who inhabit the disputed territories, and to the whole socio-political-cultural fabric of the 33 municipalities of Veracruz, 46 of Oaxaca, 14 of Chiapas and 5 of Tabasco.

Let us remember that this is an comprehensive project and, consequently, it’s not simply the passage of goods from one ocean to another through a multimodal railroad, but also includes the modernization of the ports of Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz, a parallel network of highways, 10 agro-industrial and industrial parks or corridors for the chemical, petrochemical, oil and gas industries, petrochemicals, petroleum, refineries, wind farms, hydroelectric dams, automotive and machinery assembly plants, manufacturing of other products, gas and oil pipelines, timber plantations, and high voltage power lines, as well as hotel infrastructure, services and communications for luxury tourism. All this with tax subsidies and the guarantee of basic services to investors.

From a geopolitical perspective, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec megaproject is strategic for the interests of the United States in the economic and military control of Mexico, in its hegemonic implications of dominance over the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean, and in its repositioning vis-à-vis other emerging or competing powers such as China, Europe and Japan. According to the Latin American Observatory of Geopolitics: One of the challenges of this moment concerns the hegemonic dispute between the United States and China, in which powers of nearby heights, such as Russia, are also participating. In this context, the control of space, seas, territories, routes and the elements defining positions of advantage or vulnerability, the conditions for establishing alliances, coalitions or alliances are of vital importance. Those strategic transit territories such as Suez, Panama and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec are crucial to consolidate the balances or asymmetries of world power and become rigorously guarded territories, even militarily.

It’s no coincidence that, as we anticipated more than a year ago, militarization was imposed in this case, through the handover of the administration of the Isthmus megaproject to the Mexican Secretary of the Armed Marine Corps, the military structure organically closest to the United States, and which, by the way, met last September with the Marine Corps of the United States to sign other collaboration agreements without passing through the scrutiny of the Senate. They agreed to strengthen ties and strengthen the sharing of personnel, training and logistics and troop transport operations by means of an agreement signed by the commanders of both naval forces.

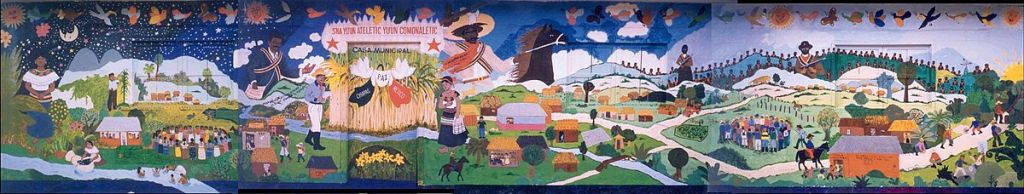

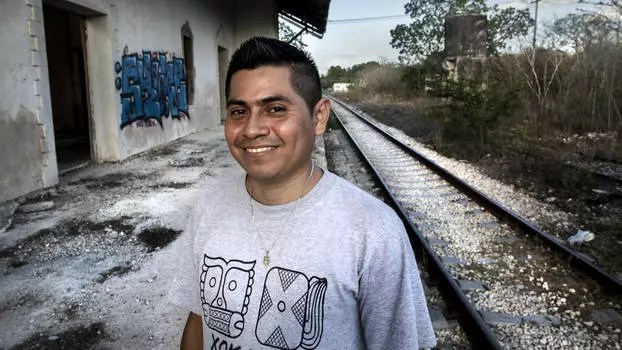

Miguel Ángel García Aguirre, founder and general coordinator of Maderas del Pueblo del Sureste, A. C., and other organizational efforts in defense of Los Chimalapas, as well as the main promoter of the National and International Campaign #El Istmo Es Nuestro (#The Isthmus Is Ours), has insisted on the special significance of the Isthmus for the country, since “it possesses ten different natural ecosystems, which to date are home to more than 10 percent of the biodiversity of the entire planet, It also possesses the most important compact forest massifs -climate regulators and oxygen producers- that still persist in our national territory, the most outstanding massif being the bioregion of Los Chimalapas, and naturally producing 40 percent of all surface water runoff (rivers and streams) in Mexico.”

Resistance against this project began in 1997 and was reactivated in 2019 with the The Isthmus is Ours campaign, whose main purpose is to prevent this triple and severe attack: against nature, indigenous and black peoples, and national sovereignty. More than a hundred organizations and social movements, NGOs and academic collectives, artists and personalities joined this campaign expressing their total rejection of the Comprehensive Development Program.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Sunday, December 4, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/04/opinion/011a2pol English translation by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

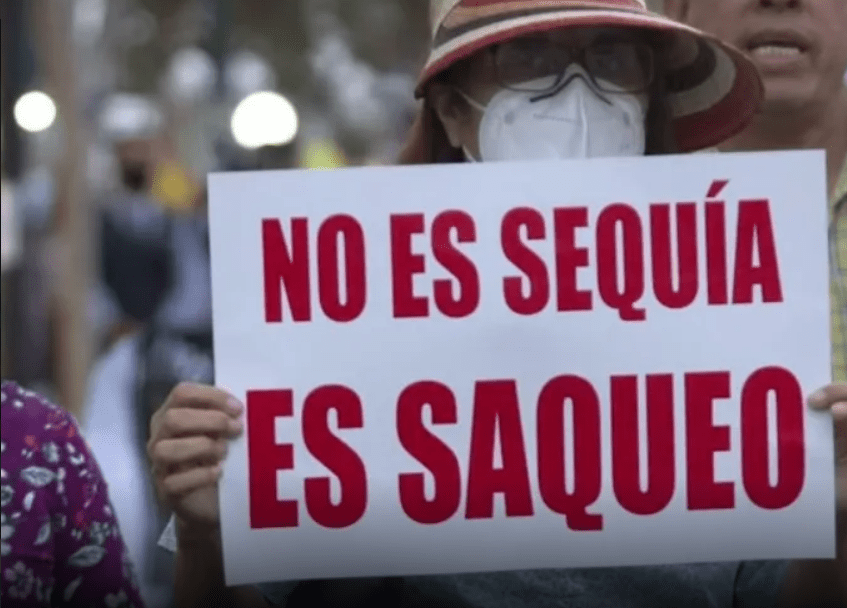

It’s not drought, it’s dispossession

By: Raúl Romero

The water crisis that shakes Monterrey, in the state of Nuevo León, generated constant social expressions of discontent throughout this year. In June, marches and other forms of protest in the northern state became the focus of national and international press attention. While ordinary people organized and demanded solutions to the water shortage, Governor Samuel García, of Movimiento Ciudadano (Citizen Movement), and his wife Mariana Rodríguez let themselves be seen carefree and even offensive on social networks: at the same time that people lived through one of the worst water crises, they published photos relaxed in the pool or leaving to shower. Its banality was not a “communication problem” or a “politically incorrect” message, it’s a common practice among juniors: exhibiting the luxuries of their opulence to differentiate themselves from impoverished sectors.

In the state of Querétaro, also during May and June 2022, different social organizations began to articulate to express their rejection of the “Water Law,” approved by the Congress of PAN majority, which reinforces the process of privatization of water through concessions, measurement and collection for up to 40 years. The articulation process led to the creation of the Network in Defense of Water and Life (Redavi), created on May 21, with the aim of organizing the rejection of the aforementioned law. Among the demonstrators who for several weeks held meetings, meetings, marches, rallies, flyers and more, were students from the Autonomous University of Querétaro, environmental activists, members of the San Francisquito neighborhood, the Agua que Corre Festival, the Bajo Tierra Museo Collective and the indigenous communities of Santiago Mexquititlán, Chitejé de Garabato and San Miguel Tlaxcaltepec.

Under the slogan “The water belongs to the people, dammit!”, the Redavi managed to get its call to reach more inhabitants of the state, while specialists and the national and international press began to place Querétaro among the states where water conflicts occur. As proof of the above, it is enough to point out that the EJAtlas-Global Atlas of Environmental Justice tool, which is responsible for mapping the different socio-environmental conflicts around the world, integrated the entry “Aggression, arbitrary detentions and criminalization of the protest against privatization of water in Querétaro” (https://bit.ly/3OXG0fJ).

As a result of the Caravan for Life and Water, the peoples united against capitalist dispossession, and with the aim of strengthening their process of articulation, different organizations and peoples met in the National Assembly for Water and Life. No more dispossession or pollution! The assembly took place on August 27 and 28 in the community of Santa María Zacatepec, in the municipality of Juan C. Bonilla, Puebla, very close to the old Altepelmecalli or house of the peoples, popular experience of occupation of a Bonafont plant that was later reclaimed by the National Guard and delivered to the transnational corporation. Organized in working groups and through generative questions, attendees shared experiences of dispossession and resistance, outlined a national diagnosis, in addition to planning joint actions and a second assembly in 2023. In particular, it highlighted the terror that communities are experiencing because of organized crime groups and the permanence of old groups of the local caciques, but now attached to the new ruling party or its allies.

Mobilizations for the right to water and against megaprojects that overexploit it are all over the country, as we have already analyzed in these pages (https://bit.ly/3B4UZPd). While state governments ignore, despise and even repress those who fight for water, in the federal spheres, particularly in the National Water Commission (Conagua), tensions and contradictions are aggravated by the abrupt departure of the deputy director of that agency, or by the alleged acts of corruption with which an official of this commission would have benefited with concessions to the Mexico Group of Germán Larrea.

“We, the Lenca people, are ancestral custodians of the rivers, also protected by the spirits of the girls who teach us that to give our lives in multiple ways for the defense of the rivers is to give our lives for the good of humanity and this planet,” Berta Cáceres told us in 2015, before she herself gave her life in defense of the rivers of humanity and of this planet. Let us learn from the Lenca people, from Berta Cáceres, and from so many other peoples and people who, by defending water, defend the life of humanity and the planet.

As the slogan says: The water belongs to the people, dammit!

*Sociologist

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Sunday, December 4, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/04/opinion/012a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The lefts in the face of Dora Maria Téllez

By: Raúl Zibechi

Some time ago, Mónica Baltodano commented that the repression of the Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo dictatorship is even worse than that of Anastasio Somoza, against whom the Sandinistas took up arms. I confess that Monica’s statement left me frozen and I thought it was exaggerated. When we followed the case of Dora María Téllez, the pieces of the regime were put together.

Last weekend her brother, Oscar Téllez Argüello, reported that Dora María would receive the title honoris causa from Sorbonne University, in Paris, France, “in recognition of a life of dedication to the defense of social justice and democracy.” From prison, she sent the message that the title, which journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro received in her name, is dedicated to political prisoners committed to freedom in their country.

“My sister expresses to you, in addition to her gratitude, her firm determination to continue the struggle despite the torture and inhuman prison conditions to which political prisoners are subjected. She hopes that this recognition will serve to highlight and create more and more awareness about the importance of denouncing every day more and more forcefully the atrocities of the Ortega-Murillo regime, which has subjected an entire people to a regime of absolute silence and terror,” says her brother Oscar.

Dora María is a prisoner in El Chipote since June 2021, accused of “treason against the country.” “There is no light even to distinguish the toothpaste on the brush,” Chamorro explained about the cell where Tellez, 67, https://bit.ly/3ielV8l, survives. Accepting the title on behalf of the prisoner, Chamorro called on leftist movements and governments in Latin America to raise their voices against the Nicaraguan regime and said, “You cannot justify a dictatorship in the name of the left. “

Therein lies the crux of the problem. If we are now not witnessing a broad campaign for her freedom and a denunciation of the Ortega-Murillo regime, it is precisely because the left and progressivism are not interested. Because they only look at power; they bet everything on power, and for the sake of power they sacrifice ethics and dignity. It has its logic: if power is everything, the rest has little importance, since it is subordinated to the greater objective.

Dora Maria makes them uncomfortable. Because of her dignity. Because of her perseverance. Because she did not give up, sell out, or give in. The left, however, is not bothered by the regime because it does not want to look in that mirror, in any mirror that will restore its obsession with power. That left that cackles “coup” every time it’s dealt a political setback, that accuses the right of its own limitations, prefers to look the other way when it comes to Nicaragua and the political prisoners tortured in the name of a “revolution,” which only exists in its imagination.

The lefts of the world owe an enormous theoretical and political debt because they never looked Stalinism in the face, as if that regime had not emerged from the very bowels of the Russian revolution. Understanding how this ferocious and criminal regime headed by Stalin was arrived at, obviously requires looking in the mirror, drawing serious conclusions that cannot consist of placing all the blame on the enemy, as is always done from that sector.

Today’s progressivism does not usually accept criticism, since it accuses the person who formulates it of being the right. For the same reason, it cannot make self-criticisms either. Without this collective exercise, it is impossible to promote change. I do not know of any Latin American progressive president who has said where he went wrong, what the mistakes or deviations were, but they always accuse others (whether the right, the empire or the movements that supported them) for the resounding failures they harvest.

Some presidents in the region are calling for the freedom of Dora María Téllez. I think it’s necessary to do so. But it’s not enough. We must condemn and isolate the Ortega-Murillo regime for repression and crimes, because although the regime says otherwise, it has a deep alliance with the United States and the Nicaraguan right. To not so is to be complicit.

In a recent article, Baltodano denounced the closure of all the spaces and freedoms, that thousands of persecuted Nicaraguans have had to go into exile and that almost 3,000 organizations were closed, which “demonstrates in a reliable way, the will of the regime to stay in power with guns and bullets” (https://bit.ly/3GRvp3T). That’s why in the November municipal elections the FSLN had no real opponents and declared itself the winner in the country’s 153 municipalities, despite an abstention of more than 80 percent.

Obsession with power, clinging to state control, repression of dissent and lack of self-criticism, link this left that calls itself democratic, with its Stalinist past. We already know that the right is worse, perhaps much worse. But always, more dangerous than the wolf, is the one who disguises himself with the skin of the lamb.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, December 2, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/02/opinion/015a1pol/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

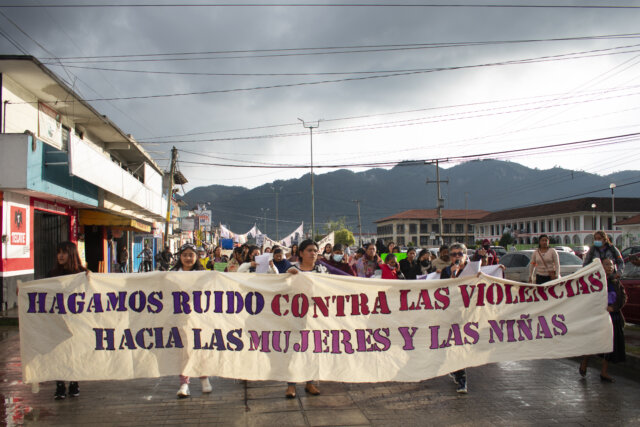

Given the increase of gender violence in Chiapas, women and girls marched on 25N

By: Orsetta Bellani

Estefanía Martínez Matías was 22 years old, she was studying nursing and worked at a clothing store in Tuxtla Gutiérrez to pay for her studies. Her lifeless body was found on November 5 on the side of a road in the southern part of the Chiapas capital, after a mobilization called by her family members and friends in front of the government palace. Six days before, the young woman had left her house to go to a fiesta from which she did not return.

For her and the other women victims of violence in their homes, in the streets, in their workplaces and in the prisons where they are held, today, on the occasion of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, marches were held in Chiapas cities, such as San Cristóbal de las Casas, Tuxtla Gutiérrez and Comitán.

According to the Attorney General’s Office of the State of Chiapas, from January to October 2022, 39 femicides were registered. Civil society organizations, however, have other data. “Doing an analysis of newspaper articles, we found at least 53 cases that have all the characteristics to be considered femicides. If a woman is killed by her partner, or when the note says that it was an assault, but in the photos, we observe that the victim has signs of sexual violence, we immediately consider it as a systemic sexual femicide,” says Karla Somoza Ibarra, director of the Feminist Observatory against Violence against Women of Chiapas.

Thanks to the struggle of organized civil society, in 2016 the Gender Violence Alert was declared in seven municipalities of Chiapas, which managed to reduce cases of femicide in cities such as Tuxtla Gutiérrez and San Cristóbal de las Casas. However, at a general level in the state the problem is increasing: according to the Citizen Observatory of Chiapas, in September 2022 there was a 24 percent increase in femicides compared to the same month in 2021 and Chiapas currently ranks fifth nationally for this crime.

Gender violence, explains Somoza, is something that women begin to experience when they are children, and the concern of the demonstrators goes towards them. “The forms of violence experienced by girls and adolescents are expressed in harassment and sexual violence in their schools, homes and streets, disappearances, trafficking and femicides,” write the self-convened and organized women of San Cristóbal de las Casas in the statement they read at the end of their mobilization. They point out that in Chiapas there are large numbers of girls forced to marry or continue with unwanted pregnancies as a result of rape and that, so far this year, 345 girls and adolescents have disappeared in the state, almost eight per week.

“Most of the minors who disappear in Chiapas are indigenous women between 12 and 17 years old, so we could say that the population with the highest risk of disappearing in the state are adolescent women,” Jennifer Haza, general director of the Melel Xojobal civil association, said in an interview. “We think that they may be victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation, and that in the case of girls from 0 to 6 years old it may be through illegal adoptions,” he says.

Melel Xojobal has been registering cases of missing children and adolescents since 2019, based on the files that the Prosecutor’s Office publishes on its portal Have you seen her? carrying out a work of systematization that the authorities do not do. In fact, the organization points out inconsistencies between the data that the Prosecutor’s Office has on its website – where 632 files of disappearance of minors appear in 2021 – and those of the National Registry of Disappeared Persons, which counted 51 cases in the same year.

The lack of articulation is perhaps the main problem that civil society organizations and marchers detect in the justice authorities. “In general, I think the Women’s Justice Centers – which are the ones that serve women and girls in the Prosecutor’s Offices – are an excellent public policy. However, there are many coordination problems within these prosecutors’ offices, which also don’t have staff who speak the language of many of the women arriving. The number of public ministries (district attorneys) is minimal, and that’s why they dismiss and divert cases with any excuse, and their headquarters are so small that they don’t even know where to place their staff,” says Somoza Ibarra of the Feminist Observatory against Violence against Women of Chiapas.

Girls, adolescents and women participated in the march this November 25 and demanded a life free of macho violence and justice for all victims of femicides. They also demanded that the authorities act to prevent the aggressions.

Originally Published in Spanish by Desinformémonos, Friday, November 25, 2022, https://desinformemonos.org/frente-al-incremento-de-la-violencia-de-genero-en-chiapas-mujeres-y-ninas-marcharon-en-ocasion-del-25n/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

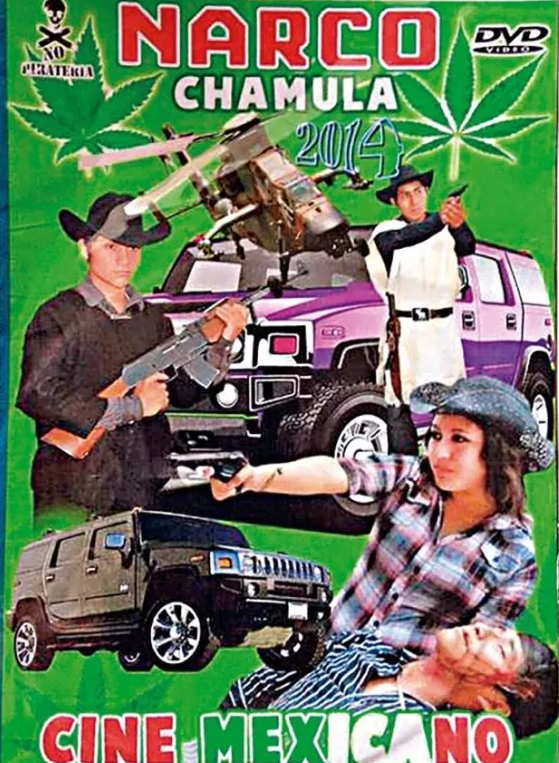

Malverde in Chamula

Jesús Malverde is a historical folk hero in Sinaloa, a sort of Robin Hood or angel of the poor. He is worshipped as a saint and believed to perform miracles, much to the dismay of the Catholic Church. Although often referred to as the “Narco-Saint,” his shrine in Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa state, is visited by a steady stream of common people, including some who work in the drug business, who pray to him for healing or protection, a good harvest or a successful journey. [1]

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

In the back seat of a luxury van, an African lion looks out the right window at the streets of San Juan Chamula. The driver of the vehicle listens to El Comando Suicida del Mayo, (The Suicide Command of El Mayo) [2] by Los Buchones de Culiacán, and shows the list of narcocorridos waiting to be played (https://bit.ly/3tL3YAN).

The scene, which seems to be taken from a TV drama, is real. It circulated on social networks at the beginning of last September. It is part of the emerging culture in this Tsotsil municipality, along with homemade indigenous pornography and the songs of Los Cárteles de San Juan: “Not only in Durango are there successful men, / in the state of Chiapas there are also badass dudes) / who wear boots and hats and have good guns.

It’s a cultural production that is manufactured and consumed by the first indigenous cartel in the country: the San Juan Chamula Cartel (CSJC), a criminal group that, instead of subcontracting its services to other gangs, decided to control the trafficking of drugs, prostitution networks, migrant trafficking, extortion, arms sales, piracy and trade in stolen cars, without intermediaries in its territories.

Although they are not the only smugglers linked to organized crime, as part of the CSJC’s activities, the martomas (a shortened form of mayordomos, a word for manservants), who used to take charge of part of the patron saint’s feast, now continue to do so, in tasks such as “good migrating.” To move day laborers from the other side of the border, they charge between 200 and 270 thousand pesos, 50-thousand for religious expenses. They get temporary visas to work in agricultural labor in Virginia, Florida and the Carolinas. At the end of their contract, the migrants remain there with the support of family networks.

The traces of the economic boom triggered by the criminal industry in Tsotsil towns and developments can be seen not only in the proliferation of ostentatious 4×4 vehicles, and in the increased consumption of the most elegant brands of whiskey, but also in luxurious residences built in a peculiar architectural style reminiscent of California, in places like Milpoleta, Moxviquil, adjacent to La Hormiga, communities near Jovel, such as El Arcotete, or in the center of Chamula itself.

The depth of drama has also been portrayed in novels. “There are forms of human suffering,” affirmed philosopher Richard Rorty, “that literature can make vivid in a way that philosophy cannot.” This is the case of La ira de los murciélagos (The Wrath of the Bats) [3], by Mikel Ruiz, a Tsotsil from Chicumtantic, San Juan Chamula, which describes the suffering experienced in the region, as well as the weave that linked power to the criminal industry before the reign of the CSJC, in a way that the social sciences are unable to elucidate.

Ruiz’s book narrates how Ponciano Pukuj, a former evangelical victim of the Chamula chiefdom protected by traditionalist Catholicism, becomes, after migrating to the United States, a very rich drug trafficker associated with El Chapo, who entrusts himself to Valverde and disputes, in a bloody and unscrupulous fight, the municipal presidency of Chamula.

Cherishing the possibility of victory, Ponciano imagines his future: “How much pleasure,” he says to himself, “it would give my friend El Chapo if he knew that I have eliminated one more stone in my path; when I am president, everything will be easier. We can even expand the business with new routes.

Pukuj faces the traditionalist Pedro Boch, who has the support of the outgoing mayor, Rigoberto de Jesús, the man of Los Zetas, who turned the municipal presidency into a center of drug dealing operations, uses official vehicles to transport Chapines (Guatemalans) with drugs and sells them birth certificates. They accuse Ponciano of being a traitor to his people and traditions, as well as appearing in the Christian film Chamula, Tierra de Sangre (https://bit.ly/3EHr0hl).

In the electoral dispute for the control of a municipality that left behind machetes only to be filled with “goat horns” (slang for AK-47’s), the candidates buy votes, give away cokes, kidnap and murder opponents, and win favors from the electoral and governmental authorities.

As a scriptwriter for a documentary for his campaign, Ponciano hires writer Ignacio Ts’unum, who wondered as a child if the Chamulas could also fly, because he had the impression that only gringos deserved to have superpowers. A literary man who in his early years did not know how to speak or read Spanish, nor did he know how to write in his own language. And in elementary school he was made to learn in Spanish.

Torn by the tragedy of his people, Ts’unum recounts that, among the young people of his generation, no one saw a future on the land or in living from the milpa. They only wanted to go to the United States. He states: “Now it is not only the whites who fuck us, today our brother bat is also our master. How many Tsotsiles have their feet on the neck of another Tsotsil? In the villages the young people dream of being mules, hit men, dealers. Their heads are full of narcocorridos, their noses irritated from snorting cocaine instead of chewing pilico (tobacco).”

Mikel Ruiz tells, through Angel, an evangelical hero, how, in order to protect their brothers of faith before drug trafficking changed everything, the religious dissidents of San Juan had to confront the traditionalist caciques who murdered and expelled them to dispossess them of their lands -under the pretext that they did not comply with ritual charges- by arming themselves and organizing the Guardián de los Murciélagos (Guardian of the Bats).

In an episode that synthesizes the political plot, Pukuj says to his rival: Nobody is legal in the fight, one moment you are rough, the next you’re the expert. Nothing is legal in these territories. A work of fiction, La Ira de los Murciélagos, The Wrath of the Bats, masterfully illuminates a part of Mexico that actually exists, in which African lions are driven around in luxury vans.

Notes:

[1] With references to Jesús Malverde, El Mayo Zambada, Los Buchones, the African lion (some drug traffickers in the Sinaloa Cartel have acquired large wild animals as pets”) and the book’s reference to El Chapo, Hernández Navarro seems to be saying that the Chamula Cartel is adopting the style of the Sinaloa Cartel.

[2] El Mayo refers to Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada García, alleged leader of the Sinaloa Cartel.

[3] The Tsotsil peoples are known as Bat people because their name translates into “bat.”

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, November 22, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/11/22/opinion/017a1pol

and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee, Schools for Chiapas and compañeros in Sinaloa.

The Article 27 Reform Fiasco: Advancement of Intensive Agriculture

By: Ana de Ita*

Thanks to the series of excellent reports, “Echos of the Agrarian Counter-reform” that La Jornada offered us last week, it is possible to take a closer look at what has happened with the agrarian question after 30 years of counter-reform.

Data from the National Agrarian Registry confirm that very little of the area of social property has been sold, about 5.3 million hectares, of the 105 million that existed in 1992, while the number of ejidos and communities has increased by more than a thousand, as well as the number of agrarian subjects with land rights, which increased by more than 2 million. Thus, the core of Salinas’ counter-reform to divest land ownership and allow it to enter the market has failed. Mexico continues to be the country with more than half of its territory as social (communal) property.

In the states analyzed by La Jornada, which are characterized by important agricultural regions, there are different mechanisms for the control of ejido plots.

In Sinaloa, only 5 percent of the parceled land has become private property, but simulated settlement, as Valenzuela explains, has been the mechanism for buying land rights from the original ejido owners. This transfer of rights affects 11 percent of the parceled land. Land renting is the widespread mechanism in the state to control large expanses of irrigated agricultural land, and through economies of scale achieve crop profitability, mainly of grains and oilseeds, which is impossible for small Sinaloa farmers who have about 10 hectares of irrigated land. Rent affects 70 percent of the ejido-owned land. Reports from Sinaloa express the difficulties of small commercial farmers in obtaining financing and marketing mechanisms that allow them to make their operations profitable, so they opt to rent their land to large agricultural entrepreneurs.

In Chihuahua, the full domain that turns ejido plots into private property affected almost a quarter of the surface area (23 percent), while the transfer of rights is not so important, less than 2 percent. Researcher Quintana illustrates how Mennonite farmers drilled deep wells in desert lands dedicated to cattle ranching to transform them into intensive agricultural land — for walnut production, for example – even without a land use change permit. The over-exploitation of the aquifers causes the reduction of water for the ejido owners who do not have the resources for this type of drilling. For the past decade, ejido owners surrounded by Mennonite colonies have been denouncing water hoarding, which has even cost several lives.

The Mennonites are also at the center of what is happening in Campeche, where 8 percent of the ejido land has become private property, and where the transfer of land rights affects 5 percent of the area. The Mennonites have managed to acquire large tracts of land through the purchase of land rights to become ejido owners. They establish chummy relationships with the Maya campesinos and extend control of their territory for intensive commercial agriculture of soybeans, in some cases transgenic, rice, corn or sorghum. They cut down the jungle and use toxic agro-chemicals that threaten Maya beekeeping and affect the health of the population, but very few dare to denounce them.

In Jalisco and Michoacán, export agribusinesses have acquired land through long-term (20 or 30 year) rental contracts with ejido owners, often on an individual basis and sometimes with ejido assemblies. In Jalisco, only 7 percent of the ejido land has been transferred to full ownership, and the transfer of rights is not significant, but the change in the crop pattern towards agave, berries and avocado for export has been drastic and competes with food production. In Michoacán only 2 percent of the land area has been privatized, but export crops such as avocado plantations predate those of Jalisco, causing forest clearing, water hoarding and contamination to the detriment of rainfed agriculture. Ejido owners and communal farmers are increasingly marginalized.

These echoes of the agrarian counter-reform show how, although the essential purpose of land privatization failed, the long-term project of substituting peasant agriculture for corporate and transnational agriculture has continued, and the ejido owners and communal farmers, with very little support and with their own efforts confront the struggle for territory and natural resources against corporate agriculture, which has the support of very powerful political forces.

*Director of the Center of Studies for Change in the Mexican Countryside. (Ceccam)

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, November 7, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/11/07/opinion/022a2pol Translated by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

The Incessant Militarization of Indigenous Communities

Daliri Oropeza brings us an account of the ongoing process of militarization of indigenous communities, the effects it has on peoples and organized resistance to stop it.

By: Daliri Oropeza

There is a history of militarization of indigenous peoples in resistance to national megaprojects that is assuming certain peculiarities in this presidency.

The look of those who carry the banner is profound. They advance in full march. The message is clear: “Against the Militarization of the Country.” “Another World is Possible.” “Stop the Capitalist and Patriarchal War against the People of Mexico, Indigenous Peoples and the Zapatistas.”

It is October 12th. The mobilization for Indigenous Resistance Day is against militarization. There is an ebb at ground level faced with the legalization of placing command of the National Guard, which is in charge of public security, under the Secretary of National Defense (SEDENA), hence the demand of the indigenous peoples, who also have memory and take advantage of the march to denounce what happens with militarization and what they have experienced in their communities with the army.

Marichuy (María de Jesús Patricio Martínez) stands out with the banner in her hand, she is a Nahua spokesperson and member of the National Indigenous Congress. Delegates from the southeast also march, one of the regions where the CNI has diagnosed a growing problem with the increase in members of the Army that carry out joint megaprojects such as the Maya Train, the Interoceanic Corridor and the Morelos Integral Project.

The presence of the army and the militarization of indigenous peoples are nothing new in the history of the Mexican State. There are regions where their presence is normalized, both as security, as well as in the daily life of the people.

So, we see the army building airports or railroads, while they train some others to be members of the National Guard (GN) and for that they build barracks everywhere, without consulting the inhabitants.

Militarization in Mexico, according to the UNHCHR, is understood as “the deployment of the Armed Forces in cities and rural areas to exercise public security functions and “combat” organized crime, as well as other situations that they consider a threat.”

“The validity of a military paradigm in public security, which may include, in addition to the use of military forces in civic security tasks: the designation of active, licensed or retired military in public positions related to security, migration, prisons, law enforcement and other civil activities; the emulation of practices of a military nature within bodies classified as civilian, the weakening of the participation of civil authorities and citizens in security issues; the priority of the use of force in security situations over longer-term alternatives”, said Guillermo Fernandez-Maldonado, UNHCHR representative in Mexico.

What we see in Mexico now is another expression of the growing militarization that had already occupied public security tasks, now takes on construction and protection tasks for the main six-year term of office, trans-presidential and, geopolitically speaking, projects anchored to international commercial interests and based on the logic of the petrol. Without forgetting that the GN is also dedicated to work to contain migration.

The expansion of the Army’s work in sectors of the economy and supposed development make me think that there are countries where they are even owners of companies. Very powerful.

Disappearances and Organized Crime in Maya territory

Ángel Sulub is participating in the march against militarization. In an interview, he tells how, despite the fact that in 1901 the end of the Caste War of the Yucatán, in which his great-grandfather participated, against the rebel Mayas of Chan Santa Cruz (Noj Kaj Santa Cruz Xbaalam Naj) was decreed. The oral history of the ancestors tells that they never saw the end of that war. A battalion remained to see that they did not rise up again for their autonomous government.

“You have to remember that the grandfathers and grandmothers did not consider themselves Mexican, but they considered Mexico as an invader that was coming to dispossess them of their territory. The grandfathers and grandmothers lived in freedom”, affirms Angel.

In the talk he recalls that it was the Mayas who lived in freedom, and not slavery as in the henequen haciendas, who stood up for their autonomy. The route of the Maya Train project passes through those lands that their ancestors cared for, now named Felipe Carrillo Puerto in Quintana Roo.

“The defense of freedom is symbolically against those of the armies. These invading armies, those armies that came to plunder. When the Mexican Army enters this community. Take this town, which was a sacred town, which preserved all the essence of the Maya peoples, their spirituality, all their practices, well, ancestral, eh? It enters and takes this community under the command of General Ignacio A. Bravo, under the command of Porfirio Diaz. Then a very serious situation begins to be experienced with the presence and military control and a very cruel phase is experienced, a very serious phase of genocide of our people. The hunt of the Maya peoples begins.”

He assures that this genocide was not for racial reasons but for political ideals, which makes it unique, and with it came a stage of forgetting and erasing the abuses of the army from memory. For this reason, he is preparing a document with the U kuuchil k Ch’i’ibalo’on Center, since the most recent thing they have experienced is the increase in militarization to build the train and the accompanying industrial, tourist, and urbanization projects.

Now they see vehicles of both the Army and the National Guard patrolling every so often, a matter of a year since they are seen daily. “It’s part of the landscape.” With the presence of members of the military, disappearances, dismemberments, murders, executions, and the increase and visibility of criminal activities also arrived. All this is new for the Maya inhabitants of Carrillo Puerto.

“We see that this dispossession of memory has worked a lot, because when we look at how the military presence has increased at this time on the beaches, in public spaces in the communities, how the military are present even in activities where there are children, participating armed in school support brigades to paint or cut hair. In different ways, it is becoming very present, we know that it is a strategy to bring the army into the communities.”

And Angel knows that it will get worse, as they saw with his ancestors. He gives an account of the community diagnosis of it:

“Very heavy, that with the increase of the National Guard army, of the military in the territory, because what we are also seeing is an increase in crime, insecurity and fear”, he says with a sort of uncertainty and sadness for what they are experiencing.

Carlos Gonzalez, agrarian lawyer and member of the CNI, warns that “Militarization in the towns is growing, at least since the government of Felipe Calderon; however, the particular situation that we see today, which is the extent to which it is worsening in the processes of dispossession and destruction of the territories of indigenous peoples, along with the territorial expansion and economic and political influence of criminal cartels, it goes hand in hand with militarization. We see this increase in the processes of dispossession from very specific infrastructure megaprojects such as the Maya Train, the Interoceanic Corridor and the Morelos Integral Project. And they intend to reorder territories, borders and populations in the geopolitical logic of the United States government. More impetus has been given to mining together with an aggressive hydrocarbons policy.”

With living hope and memory, Angel participates in the U kuuchil k Ch’i’ibalo’on Center, along with its members, carrying out activities to strengthen the Maya roots that link them to the territory, thus the love for the territory, to safeguard the wisdom of the grandmothers, of the grandfathers, the value of being Mayan and for the care of the land, so that “the defense of the territory, the protection of the land, then comes by itself.”

“There will always be hope. It is true that the panorama before us is very tough and that as we know what is to come, it is going to be worse and worse for the territories. But there is the hope that in the struggles, the resistance, the solidarity efforts, the community efforts, they will also grow. In our body, in our memory, from our families in such a way that, eh, the defense of the territory, the protection of the territory, well, it comes by itself”, says Angel.

For Carlos Gonzalez there is a continuity of neoliberal macroeconomic policies, such as free trade that intensified with the USMCA or the policy of raising financial interest rates for speculation.

The diagnosis made by the CNI in September, with towns from more than 20 states, in the framework of its most recent extended meeting of the Monitoring Commission, gives an account of this:

“The National Guard is a guard which is not civilian. From the beginning it was fundamentally made up of soldiers and directed at all times by soldiers. Already with the reforms that were approved, we are talking about militarization or the growth of militarization. The National Guard goes to practically all the municipalities of the country, intending to establish a barracks, an operations base, and that is having an impact, above all, on indigenous communities.”

This happens in indigenous peoples of the CNI but also in many that are not organized in this network but have a history of resistance and struggle for land, such as the Yaqui Tribe. Just the three municipalities where they live are classified as the most violent in Mexico: Guaymas, Empalme and Obregon, according to information from the Ministry of Public Security. Only Vicam Estacion and Loma de Bacum, two Yaqui towns, participate in the organization. But those who denounce this time are from Huirivis, one of the furthest communities.

Flavio Buitimea is the name he chooses for security reasons. Flavio recalls that before either the police or the military entered his territory, but since the Justice Plan entered, he has seen how the National Guard enters and patrols the main streets and, in his town, they have even entered private homes on supposed operations that scared the population. He hasn’t forgotten that it was the Army that enslaved them and took them to the henequen haciendas of the southeast to work. They do not forget that the Army bombed their territory, also ordered by Porfirio Diaz. They called them “The Bald Ones.”

“The growth of violence produced by the cartels works as a pretext to militarize, but militarization is not serving to stop this violence. Where there is a military presence, there is violence, there are murders, there are disappearances, there are all kinds of crimes. It’s not working”, assures Carlos.

“Analyzing this process with the CNI, of militarization and para-militarization, of war against the communities, of growth in the processes of dispossession, of exponential growth of drug addiction and alcoholism in indigenous communities and peoples, we are worried about the whole country.”

Carlos sees that there is a clear intention to mobilize the National Guard and the military to stop migration and to protect these megaprojects, and on the other hand, to surround organized towns and communities such as the Zapatistas.

There are towns like Milpa Alta, San Nicolas Totolapan, Ostula, which by decision of the assembly, carrying out their right to self-determination, denied entry to GN barracks or bases. They stopped them.

Carlos Gonzalez recalls that the constitutional and conventional framework indicates limitations to the presence of the military in indigenous territories:

“Article 30 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that the presence of the military in indigenous territory can only be agreed upon through consultation with the affected communities and they are not doing so. They are ignoring the decision of the communities and if they are not established it is because there is opposition and a decisive rejection of the communities.”

With this example, there is still hope for the attention of the peoples facing militarization.

Originally Published in Spanish by Pie de Página, October 26, 2022, https://piedepagina.mx/la-incesante-militarizacion-en-pueblos-indigenas Translation by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee