Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Organized crime and extractivism

By: Raúl Zibechi

Organized crime, parastate or drug trafficking, are the forms assumed by accumulation by dispossession/extractivism in the zone of non-being, that is, in the territories of the native, black and campesino peoples of Latin America. Although they are usually presented separately, as if they had no relationship, criminal violence, nation-states and the economic model form the same framework for the dispossession of peoples.

This conclusion is indebted to the work of the researcher Emiliano Teran Mantovani in a recent essay in which he links the three indicated modalities. [1] We know that organized crime dispossesses the commons from the peoples, breaks community fabrics, exploits and murders people, in addition to degrading the environment with its “economic” initiatives, with the support of both private companies and the states.

What most interests me about Teran’s work is his analysis, which considers organized crime as extractivism, from the displacement and intimidation of populations to the control of mines and productive territories, ending in the management of the “processes and routes for commercialization of the commodities.”

In his opinion, we must think of organized crime as “a clear expression of the politics of extractivism in the 21st Century,” therefore far beyond the economic dynamics it represents. On this point, I see a close relationship to the thinking of Abdullah Öcalan, when he maintains that: “capitalism is power, not economy.” In its decadent phase, capitalism is armed violence and genocide, however hard that may be to accept.

In one of his more brilliant pages, Teran establishes a gradation of crime’s way of acting, which takes us back to the a dawn of capitalism described by Karl Polanyi: subduing the local population through terror; control of economic forms seeking monopoly; incorporating a part of the population into the “criminal” economy, protecting that sector with its own services, naturalizing violence and, finally, converting “part of the population into war machines” by integrating it “subjectively, culturally, territorially, economically and politically into their logic of organized violence.”

The points of confluence between organized crime and extractivism are evident: they both confront the population that resists or doesn’t fold, they are both based on the same economy of dispossession and they both seek the protection of weapons, those of the State and their own.

There is something else, very disturbing: organized crime “has achieved becoming more and more a channeling factor for discontent and popular unrest, also being able to capture a part of the counter-hegemonic impulses of revolt, of antagonism with power, and potentially giving shape to possible insurgencies,” Teran maintains.

Terrible, but real. That should lead those of us who still want fundamental anti-capitalist changes to reflect on what share of responsibility we have in this decision of so many young people to join the criminal violence.

A first issue is to break with the desire to mask reality, of not wanting to see that the capitalism that really exists is a war of dispossession or fourth world war, as the Zapatistas call it. Crime and violence, in order to become the principal mode of capital accumulation, must have the support and complicity of the states, which are being converted into states for dispossession.

That’s why the problem is not the absence of the State, as progressivism says. We gain nothing by expanding its sphere, it being the primary one responsible for violence against the peoples.

A second issue is to understand that “the social fabrics are in themselves a battlefield, a disputed field, as Teran points out. Crime, narco-paramilitarism (inseparable from the State’s armed apparatus), are determined to break social relations to rearrange them to serve their interests, hence the racist violence and the femicides.

That’s why the self-defense groups anchored in the communities that resist have become essential. Not only must they defend and care for life and nature, but also human relations.

Lastly, not just a few intellectuals talk about the “alternatives to extractivism,” always thinking in technocratic terms and that they will be implemented from above. Impossible.

Today, the real alternatives are the Indigenous Guards, Cimarrons [2] and Campesinos of the Colombian Cauca, the autonomous governments and autonomous demarcations of the Amazon, the recuperation of Mapuche lands; the Zapatista National Liberation Army, the CNI, the bonfires of Cherán, the community guards and the multiple forms of self-defense. There are no shortcuts, only resistance opens paths.

Notes:

[1] Emiliano Teran Mantovani, “Organized crime, illicit economies and geographies of criminality: other keys to thinking about extractivism of the 21st Century in Latin America,” in Conflictos territoriales y territorialidades en disputa, Clacso, 2021.

[2] Cimarron – A Maroon (an African who escaped slavery in the Americas, or a descendant thereof), especially a member of the Cimarron people of Panamá.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, January 13, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/13/opinion/011a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

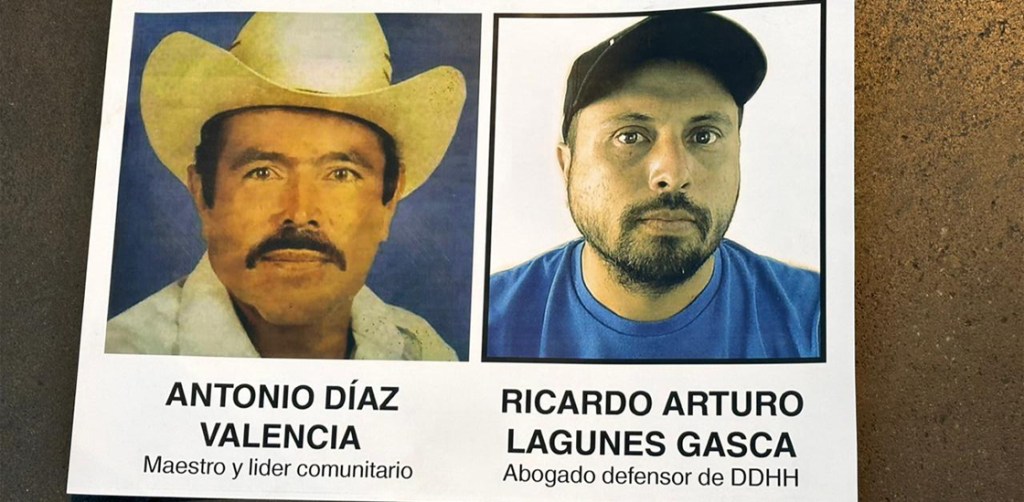

Disappeared defenders

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

As I write this, two weeks have passed since the violent kidnapping of Ricardo Lagunes Gasca and Antonio Díaz Valencia in the vicinity of Cohuayana. Their whereabouts are not known nor exactly who took them away, although the suspicions fall into the category of “it was organized crime. “For the time being, they are entering the atrocious and very long list of people who disappear in Mexico. Each “case” is a life, a story, a human totality. Who are the two activists who were taken from their vehicle on January 15 and have not been seen again?

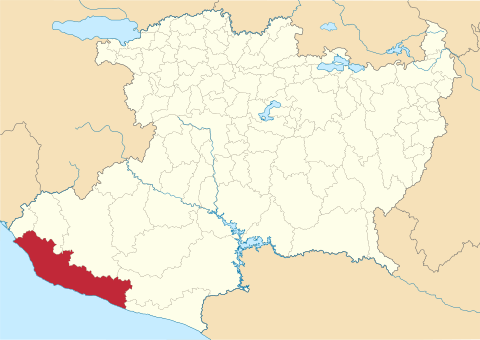

In its urgent action, the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center says of Antonio: “He is a comunero (communal member) of Aquila who has defended the environment and who has confronted representatives of the iron company (Ternium), which counts on unconditional people. At this time, the change of the communal assets commission has been scheduled and the situation has been polarized due to the fact that the company’s interests managed to be imposed inside the agrarian nucleus and have also been involved in this election by supporting the group benefited by the company.” Antonio represents a danger to the mining company “because he has denounced the grave damages that the extraction of the mineral by means of open sky mining is causing and the company fears that the signed agreements will be revoked.”

Aquila has, for decades, been one of the country’s most dangerous and ungovernable regions. One breathes the narco economy there, which frequently coincides with mining concessions of multi-million-dollar importance. If money attracts money, savage mining attracts the narco, or takes advantage of it. As a collateral business to their own interests (trafficking of drugs or people and violence itself, that big business) criminal groups clear the path for machines and extraction of obstacles. Since 2009, 35 community members have been killed and five more are still missing. The violence doesn’t stop.

Tlachinollan says: “The territorial dispute has been ironclad, not only because of the interests of organized crime, which seeks to control the territory of this Nahua community, but also because there are mining concessions such as Ternium that for years has divided the community.” Just last January 12, three members of the community round were killed.

Ricardo is one of those lawyers who, instead of enriching himself with his profession, put himself at the service of those who suffer the law and illegality without economic resources to defend themselves from the aberrations of “justice” with deep, root reasons in their claims. Ricardo always litigates and fights for communities with courage and even recklessness. He accepts difficult and dangerous cases. Not infrequently the exercise is controversial.

Ricardo belonged to the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) for a while. Then, and afterwards, I had the opportunity to accompany his accompaniments. Brilliant, effective, he joined the territorial defense of two large ejidos, San Sebastián Bachajón (Tseltal) and Tila (Chol), both adherents of the Other Campaign. In September 2009, he was nearly killed in Jotolá by members of the counterinsurgency Organization for the Defense of Indigenous and Campesino Rights, which operated in Chilón and Tumbalá. His attackers were released soon after, but he didn’t flinch.

The assurance of his audacity has made him conflicted. At some point he broke with Frayba and made harsh (in my opinion unjustified) accusations against it and Bishop Raúl Vera, president of the organization. He took on the representation of a minority group that split from Las Abejas de Acteal, seeking “reparations” for the 1997 massacre and displacement in Chenalhó. He took the case internationally, confronting his former colleagues.

He soon assumed the territorial defense of other localities. On the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, he filed an injunction against the wind companies. He litigated for communities in Yucatan and Campeche. He has spent five years accompanying the Nahuas of Aquila in their resistance against the transnational mining company Ternium, which his disappearance and that of Antonio objectively benefit.

He founded Legal Advice and Defense of the Southeast. According to Front Line Defenders, “it has succeeded in protecting thousands of hectares of collective lands, valuable ecosystems and collective rights. It has also achieved the protection of indigenous communities before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights “

Several times a columnist for La Jornada, he exposed denunciations and allegations of justice from below to give relevance to their struggles. I saw it in action in courts, prisons and communities in Chiapas. I know his talent and commitment.

Tlachinollan points out: “The violence faced by community defenders and environmentalists is worrisome” in contexts where criminals have taken regional control. “Instead of protecting those who defend their territory, the authorities have colluded with the mining companies and the heads of organized crime.”

In Mexico no one defends the defenders of the prisoners and the communities that, without them, would be left without legal defense. This is one of our miseries. Ricardo and Antonio must appear now. Alive.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, January 30, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/30/opinion/a08a1cul and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Radical artistic wealth blossoms in the southeast; in the Muy Gallery, a show

Located in the coleto [1] barrio of Guadalupe, the space is a living museum and supplier of plastic work of creators from Chiapas indigenous communities // It exposes and sells the work of painters, potters and photographers, such as Maruch Méndez, PH Joel and Marco Girón.

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

San Cristóbal de las Casas

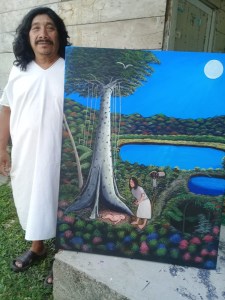

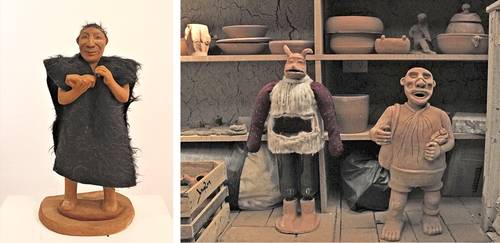

The Muy gallery (root of the Tsotsil word meaning “pleasure”), established in an old house in the coleto neighborhood of Guadalupe, beautiful and rustic, is a container and a supplier for the plastic work of artists from indigenous communities in Chamula, San Andrés, Tenejapa, Ocosingo, Huixtán, Las Margaritas, Rayón and other municipalities. About twenty painters, sculptors, ceramists, embroiderers, photographers, engravers, videographers or digital creators of Tsotsil, Tseltal, Zoque, Tojolabal and Chol origin are represented by Muy. They frequently create here, in the gallery workshops, their paintings, clay works, installations.

It is a living museum and a school where tradition and contemporaneity, even avant-garde, go hand in hand and produce pieces of the imagination that do not need to ask permission to be considered Art. They participate in the indigenous awakening of Chiapas, which in the past 30 years has produced literature and revolution, painting (mural and easel) and cooperatives, a curious mixture of the communal and the personal.

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, the encounter of the traditionalist indigenous peoples of the Highlands of Chiapas with a sudden cosmopolitan modernity and of all Mexico, often enlightened, via tourism, and also, paraphrasing Maurice Ravel, for various noble or sentimental causes, had a great cultural effect. Over time, rebels, liberationists, writers, artists sprang from the mist of the mountains and the green curtain of the jungle. The invisible ones became visible.

A couple of rooms for the exhibition and sale of the work. Muy artists’ work offer a sample of the pictorial wealth and radical craftsmanship that is taking place in these regions of the southeast. Some self-taught, others formally educated and even professionals, born between 1957 and 1997, have in common the undeniable condition and aesthetic commitment of the artist.

Crossing a small garden is the large room for temporary exhibitions, this time with numerous pieces of clay, ceramics and sculpture by P. T’ul Gómez (Chonomyakilo’, San Andrés, 1997) and other potters. Some pieces seem to have just come out of the ground, in others a rereading of Picasso, Soriano or Toledo appears. All together and scrambled. High-flying pottery.

On one side, with the guidance of Darwin Cruz, another artist of the house, a Chol originally from Sabanilla (1990), La Jornada visits the tumultuous workshop-cellar of the artists, where the chaos of figures and objects seems to come alive. Cruz shows his own finished or in-process work, sculptures and prints. His painting, which is not here, portrays a tremendous reality. There are also works in progress by PH Joel (Francisco Villa, Ocosingo, 1992), anthropologist and ceramist between the neo-Maya and the phantasmagoria of a dream of gods and cyborgs.

Explosive and refined proposals

The list of artists represented by the gallery is wide and varied. There is the painter and potter Maruch Méndez (K’atixtik, San Juan Chamula, 1957), with an original “innocent” power. Juan Chawuk (Tojolabal from Las Margaritas, 1971), renowned painter, who has exhibited abroad, stands out for a painting, sometimes a mural, loaded with provocative eroticism and irony, not far from the tragicomic realism of Raymundo López (San Andrés Larráinzar, 1989).

Also known are the painter Saúl Kak (Nuevo Esquipulas Guayabal, Rayón, 1985), who adds to his explosive and expressive work an environmental and cultural activism in the Zoque region, and Antún Kojtom (Tenejapa, 1969), with a characteristic, neo-figurative, post-cubist style, sober in color, intense in its representation.

Maruch Sántiz (Cruztón, 1975), with extensive experience, was one of the first indigenous photographers in Mexico, with “portraits of things” who knew how to speak. His “little brother” Genaro (Cruztón, 1979) from a very young age followed in his footsteps and today is an elegant photographer of nature and detail.

The linguist, university teacher and translator Säsäknichim Martínez Pérez (Adolfo López Mateos, Huixtán, 1980) has developed a bold practice of photo and video, as well as textile intervention. Cecilia Gómez (Chonomyakilo’, San Andrés, 1992) seems closer to the “craftsmanship” of embroidery, but with a radical free touch.

They are joined by Gerardo K’ulej (Huixtán 1988), who makes spatial and sculptural interventions of inexplicable balance and refined sobriety, and Marco Girón (Tenejapa), experienced photographer and web designer.

Another realist painter is Carlos de la Cruz (San Cristóbal, 1989), who transitions naturally from coal to mural. Manuel Guzmán (Tenejapa 1964) practices the wild expressionism of a Kandinsky votive offerings painting. Somewhat predictable, and notable however, is the Lacandón Kayúm Ma’ax (Naha, 1962); he is related to the Amazonian painters of Ecuador, and like them he portrays dreamlike landscapes that replicate from here the customs officer Rousseau .

This tour closes the interconnectivity of the writer Xun Betan, Tsotsil of Venustiano Carranza and also a member of the Muy gallery, founded by John Burnstein, and currently directed by Martha Alejandro, originally from the Zoque region.

[1] Coleto is a word used to describe residents of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, who believe they are direct descendants of the Spanish invaders.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, January 24, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/24/cultura/a03n1cul and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Violence against the Indigenous Peoples

By: Francisco López Bárcenas

Popular predictions at the beginning of the year announced that January would bring storms, but few imagined the magnitude of them. The violence against indigenous peoples in this first month of 2023 has acquired such dimension and modalities that it gives us much to think about. In such violence, community mobilizations in opposition to megaprojects are repressed, and community guards responsible for providing security to the peoples of which they are a part are assassinated. Likewise, defenders of communities in struggle are disappeared and community authorities who defend the rights of those they represent are arrested, without any foundation or motivation. All this in a context where human rights organizations denounce that the country is one in which the most violence is exercised against human rights defenders.

One constant in this violence is that it is presented in regions where they generate the most opposition to the emblematic projects of the federal government. This is the case of the repression that was exercised on January 9 against inhabitants of Nuevo Paraíso, Campeche, who had blocked work on the Maya Train. The police action began at noon and involved five units of the state prosecutor’s office with at least 40 heavily armed elements, two of the Mexican Army and about 16 troops, two patrols of the state preventive police with about 10 agents, two units of the National Guard composed of 10 people, as well as three Fonatur vans. Excessive force unnecessary to accomplish its goal, but necessary to instill fear. In the action, several people were beaten and two identified as responsible for the blockade were arrested.

This is also the case of the arrest of David Hernández Salazar, municipal agent of the Puente Madera community, municipality of San Blas Atempa, where the construction of an industrial park for the operation of the Trans-Isthmus Corridor, another of the emblematic works of the federal government, is planned. His arrest occurred on January 17 in the city of Tehuantepec, in compliance with a court order, for the crimes of fire damage and intentional injury. His compañeros mobilized and denounced his disappearance, with which they achieved his freedom, which makes them suspect that the authorities intended to charge him with invented crimes in order to stop him, and to thus stop opposition to work on the Trans-Isthmus Corridor.

Another form of aggression against the indigenous peoples, in which no governmental institutions participate directly, but have responsibility due to their omission, is the murder of opponents of the regime. As Magdalena Gómez wrote in these pages: “Last January 12, three members of the communal guard of Santa María Ostula and the community guard of Aquila municipality were murdered: the community members Isaul Nemecio Zambrano (of Xayakalan), Miguel Estrada Reyes (of La Cobanera) and Rolando Mauno Zambrano (of La Palma de Oro). The crimes were perpetrated at a vigilance point near the municipal seat of Aquila, by a commando of some 20 members of one of the criminal groups that operate in the area.” No one in the government has said anything in that regard.

The most recent case is the kidnapping and disappearance of human rights defender Ricardo Lagunes Gasca and the leader of the indigenous community of Aquila, Michoacán, Antonio Díaz Valencia, on Sunday, January 15 on the highway between Aquila and Tecomán, Colima. According to the public denunciations of their compañerxs and of human rights organizations –including the representation of the United Nations Organization in Mexico–, the lawyer “was accompanying the Nahua community of Aquila in the legal defense of its communal land, coveted for many years by mining companies that operate at the limit of legality and in collusion with organized crime groups.” As in the previous case, the aggression has not occasioned any statement from any authority, despite their obligation of proving security to the population.

One of the characteristics of capital at this juncture is the control of spaces in which to operate and the speed of its movement. On them, as well as on the dispossession of natural goods depend their profits, not on the exploitation of labor to produce surplus value, as in past times. And both the spaces and the resources that interest it are located in indigenous territories. That may explain so much legal and illegal violence against them. What is not explained is that a government that declares itself anti-neoliberal maintains the patterns of repression of its predecessors, from which it seeks to distance itself. Care should be taken with this, because violence generates violence and peoples also get tired of always providing the deaths.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, January 23, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/23/opinion/015a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

An Indigenous cultural awakening radiates with intensity in San Cristóbal

In Ciudad Real de los Altos a scenario like few others has been created, in which creativity, art and literature flourish in cafes, galleries and bars where Tsotsil and Tseltal writers, plastic artists, filmmakers or academics gather

By: Hermann Bellinghausen, Envoy

San Cristóbal de las Casas

To commemorate International Maternal Language Day (February 21) and in tribute to indigenous peoples, in 2022 Darwin Cruz made the oil painting Lajkña Ch’ol (left), a symbol of the campesino community that continues to work the land and resists changes in contemporary societies, the artist shared on his Instagram account.

The awakening, or rather, the indigenous awakenings that have been experienced in Mexico during recent decades created cultural scenarios of their own, but few like that of the arrogant Ciudad Real in the Highlands of Chiapas. Outside the national spotlight, the cultural activity of authors, collectives and promoters may go unnoticed, but here it is breathed intensely.

In cafes, restaurants, galleries and bars writers, plastic artists, filmmakers or academics gather, of Tsotsil and Tseltal origin, mainly. It is not irrelevant. San Cristobal de Las Casas used to be one of the most openly racist places in the country. Disdain for the Indians was inherent in the dominant population, kaxclán or “white.” Maya women and men were invisible, poor, cannon fodder. They had to give the sidewalk to the coletos. They were worth “less than a chicken,” according to the finqueros (estate owners).

In a little more than 30 years that changed radically. Not that the discrimination has dissipated, but it is now shameful and quiet. What’s indigenous, and feminine indigenous, are fashionable, if you will. No wonder. In itself, the tourist attraction of Ciudad Real was, despite everything, the indigenous crafts and the atmosphere of the campesinos and merchants who came from the mountain villages.

The Zapatista imprint was felt in the local Maya culture almost immediately at the end of the twentieth century, as a sequel to the uprising and political activism of the rebels. For the same reason, it also became a destination for thinkers, writers, filmmakers from all over the world, but that is not what is talked about here.

Today there is a young but rich bilingual literary corpus in Tseltal, Tsotsil, Chol and Zoque. It would be lengthy to list the poets and storytellers who have published and given readings in these years. Much poetry and stories, far from ethnographic folklore, are accompanied by the theoretical reflection of authors such as Mikel Ruiz, Delmar Penka or Xuno López Intzin. Translators and cultural promoters such as Xun Betan, the Chamula poet Enriqueta Lunez, the Chol poet Juana Peñate and the teacher Armando Sánchez are here. Book publishing is difficult and of restricted circulation, but incomparably more widespread than before.

Photography, painting, cinema and gastronomy

From the admirable traditional craftsmanship have emerged photographers such as Maruch Santiz, painters and plastic creators such as Juan Chawuk, Saúl Kak, Pet’ul Gómez, Antún K’ojtom, Darwin Cruz, Säsäknichim Martínez, to mention just a few.

In the modest yet lavish Zapatista autonomous stores one finds the eloquent naïve oil paintingsof the Zapatista Caracol of Morelia. Now there is a caracol in San Cristóbal: Jacinto Canek, a place of meeting and reflection for indigenous people from the region’s communities and the municipality of San Cristóbal itself.

Training and production support programs such as ProMedios, ImagenArte, Tragameluz, Sinestesia, Ambulante have left their mark and given rise to a new documentary film and a new photography. We have recent films, such as those of Xun Sero, María Sojob, Juan Javier Pérez and others that already parade through film libraries, festivals and platforms.

There are key antecedents such as the cooperative Sna jtzi’bajom (since 1982), the Taller Leñateros, the school for writers in the Los Amorosos bar in the 90s, the Chiapas Photography Project. Today we find important spaces, such as the Muy gallery, dedicated to promoting the creation, exhibition and promotion of Maya and Zoque artists, where one finds canvases, engravings, sculptures and installations of important aesthetic value.

A new Chiapas Maya cuisine flourishes in successful gallery restaurants such as Taniperla, where good pizzas and tasty stews are added to a jungle cuisine based on banana, Creole corn, flowers, chiles and leaves of the Lancandón. Even the debatable pox today has tourist stores, as well as coffee and honey from cooperatives and autonomous municipalities, which also promote cultural spaces.

Although in other parts of the country there is a similar indigenous cultural profusion, such as Oaxaca and Mexico City, in San Cristóbal it is more unexpected and visible. Although public institutions in the sector play some role, they are not as successful as independent indigenous enterprises, projects and cooperatives.

Nor is the scientific and cultural effect of the Colegio de la Frontera Sur, the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the State Center for Indigenous Languages, Art and Literature, the Union of Mayan Writers-Zoques, the cultural collective Abriendo Caminos José Antonio Reyes Matamoros or Cideci-Universidad de la Tierra, as well as public universities (Autonomous University of Chiapas, University of Sciences and Arts of Chiapas, Intercultural). All with work frequently directed to resources, ethnology, linguistics and biology in indigenous territories, with a growing presence of students and researchers from indigenous peoples, almost always bilingual.

In the midst of a simultaneous social decomposition that affects the state’s communities, the product of corruption, paramilitarism, criminal violence, massive migration northward and aggressive urbanization, the now dangerous Jovel Valley also appears as a novel melting pot for the arts, research and dissemination of those who until recently were seen only as peasants, street vendors, artisans and beggars. The indigenous cultural change that San Cristóbal de Las Casas radiates is profound.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, January 23, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/23/cultura/a06n1cul and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

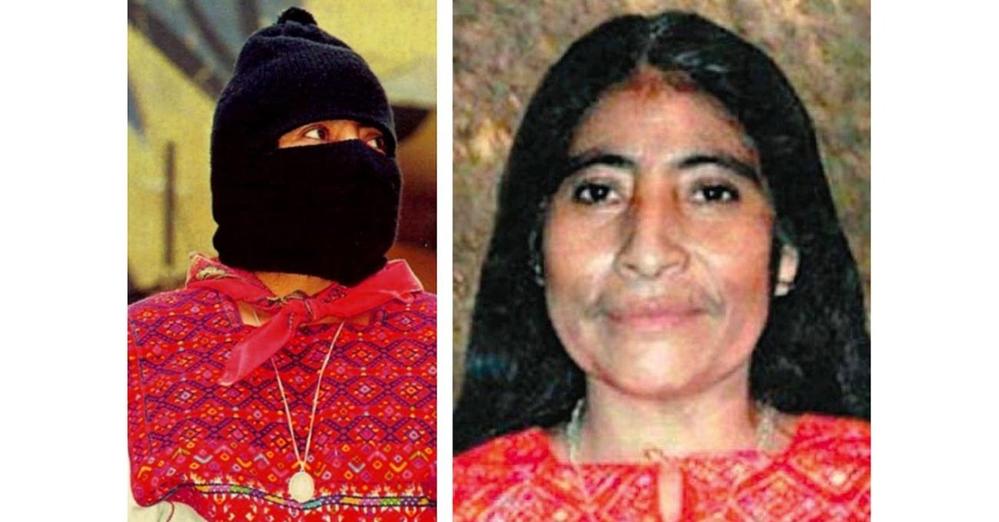

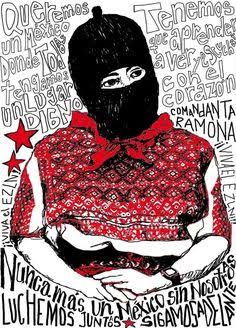

Comandanta Ramona: the first of many steps

By: Raúl Romero*

On October 12, 1996 in the Zócalo of the capital, in front of thousands of people, a small woman with a giant heart, brilliant eyes and a sincere gaze, dressed in a white Tsotsil huipil with red embroidery, and covering her face with a ski mask, took the microphone and pronounced an important message: “I am Comandante Ramona, of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional). I am the first of many steps of the Zapatistas into the Federal District and all parts of Mexico. We hope that all of you will walk alongside us.”

It was the first time that a member of the Indigenous Revolutionary Clandestine Committee of the EZLN (Comité Clandestino Revolucionario Indígena del EZLN) arrived in the city, which meant not only breaking the military siege, but also reenforcing the dialogue and meeting with many other native peoples and social sectors of Mexico: “We came here to shout, along with everyone, that never again a Mexico without us,” Ramona said. And she continued: “That’s what we want, a Mexico where we all have a dignified place. That is why we are ready to participate in a great national dialogue with everyone. A dialogue where our word is one more word in many words and our heart is one more heart within many hearts.”

In clandestinity Comandanta Ramona had played a key role inside of Zapatismo. She participated in a revolt inside the revolt, or what the late Sup Marcos called the “EZLN’s first Uprising.” Together with Comandanta Susana and other women, before January 1, 1994, Ramona promoted the “Women’s Revolutionary Law,” a document that among other points established that “women, without importance to their race, creed, color or political affiliation, have the right to participate in the revolutionary struggle in the place and grade that their will and capacity determine.”

Ramona became the most visible figure for several generations of Zapatista Maya women who went from living in submission to the colonialist, patriarchal and capitalist structures, to being at the front of a political-military insurgent organization. Let’s remember, for example, that in the middle of 1993 Chiapas finqueros (estate owners) exercised the “derecho de pernada” in the families of their peons; in other words, they practiced their “right” to rape women who married one of their peons. In 2013, regarding the escuelita zapatista (little Zapatista school) –an initiative in which the Zapatista communities showed thousands of people from all over the world their achievements in everyday life–, different women support bases told how that practice led to the “Women’s Revolutionary Law.” The exercise was fantastic, and also led to a proposal to expand the law with 33 new articles.

In May 2015, 20 years after the war against oblivion, at least six generations of Zapatista women, shared their word on how the situation has changed for women in those 20 years. The stories, compiled in the “The struggle as Zapatista women that we are” section of the book titled Critical thought versus the capitalist hydra I, are exceptional documents of collective and trans-generational self-evaluation. There, the Zapatista support base Lizbeth said: “We as […] young Zapatistas of today, no longer know what a capataz (foreman) is like, what a landowner or boss is like […]. We now have freedom and the right as women to give our opinion, discuss, analyze, not as before.” In the same sense, in April 2018, at least six generations of Zapatista women would recount the advances and the challenges of Zapatista women.

Comandanta Ramona died on January 6, 2006, but her steps continue resonating in Zapatista Chiapas, in Mexico and in the whole world. In 2019, in the Seedbed “Footprints of Comandante Ramona,” the 2nd International Gathering of Women Who Struggle with thousands of women from different countries would be celebrated, and in 2021, the “Zapatista Land-Sea Training Center” would be installed there,” the place in which the almost 200 Zapatistas who would later travel by ship and by plane to rebellious Europe would stay.

Comandanta Ramona was the first of many steps of the Zapatistas into the Federal District, and she was also the first part of a long road ahead: one that has led them to travel to other parts of the world, and that has also invited them to rethink the multiple dominations in exploitive relationships. 29 years after the war against oblivion, Zapatismo continues to be a dream that encompasses many worlds, and Comandanta Ramona became a star that guides their navigation.

* Sociologist

Twitter: @RaulRomero_mx

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Wednesday, January 11, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/11/opinion/015a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Massacre in Peru: Democracy at war against the peoples

By: Raúl Zibechi

“In the Andes massacres follow one another

with the rhythm of the seasons.

There are four in the world; in the Andes there are five:

spring, summer, autumn, winter and massacre.”

Manuel Scorza

On January 4, a regional strike began in the country’s south, which had been interrupted in December by the Christmas holidays. More than 60 road blocks (especially in Cusco, Apurimac, Ayacucho, Huancavelica, Puno), demanding elections in 2023 and the resignation of Congress, which has only 8% support in the population.

On January 9, tens of thousands of Aymara community members entered the city of Juliaca, the largest in the department of Puno, in a peaceful demonstration that was repressed from helicopters with tear gas and from the ground by police who fired bullets that exploded in bodies (https://bit.ly/3GBlOw2 ). In addition, police fired gas at nurses and medical personnel who attempted to treat the wounded, beat doctors and firefighters and according to some reports stole medicines.

The result was 17 deaths, adding up to a total of 48 killed since Pedro Castillo’s former vice president, Dina Boluarte, assumed the presidency. Almost all the deaths happened in three hours, between 3 p.m. and 6 p.m., according to detailed accounts by the newspaper La República. To the dead must be added around 300 wounded, including children and journalists, especially in the regions of the Quechua and Aymara peoples of Apurímac, Ayacucho, Puno and Arequipa.

These are the crimes of Peruvian democracy, of a political caste that has always governed the country from a racist State “whose decomposition Fujimorism initiated, continued with the other governments, parties and businessmen corrupted by Odebrecht, and that today murder to continue in the distribution of power,” as a statement from social organizations points out.

These are crimes endorsed by a parliament that is corrupt to the core. Proof of this is that the plenary session of Congress shielded, on the same day, the parliamentarian Freddy Díaz who is investigated by the Public Ministry for the sexual rape of a Legislative worker in his own office (https://bit.ly/3X0mJ08).

Hours later, the same Congress gave a vote of confidence to a government that carries more than 40 deaths on its back and when the Prosecutor’s Office is beginning to investigate the president, the prime minister and the ministers of Interior and Defense, for “crimes of genocide, qualified homicide and serious injuries committed during the demonstrations of the months of December 2022 and January 2023 in the regions of Apurimac, La Libertad, Puno, Junín, Arequipa and Ayacucho” (https://bit.ly/3CBFUVW).

What is called democracy, are totalitarian states in the Andes where only the heirs of the landowners, today mafia businessmen who dominate the media and illicit economies, can govern. That is why a military coup is not necessary in Peru, because the media (in particular television) are absolutely controlled, don’t report on massacres and refer to protesters as “terrorists.”

Under these conditions, new elections will only guarantee the continuity of authoritarian and corrupt governments, as has been the case since the 1980s, a situation aggravated by the current dominance of mafia economies.

If it were true, as Noam Chomsky has just pointed out, that “a better world is within our reach” and that “Another world is possible,” we should reflect on what paths to take to get closer to that goal.

The Amazonian peoples grouped in Aidesep (Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Jungle) are mobilizing against the government, like the other peoples of Peru. But they also point towards the creation of autonomous territorial governments (as Wampis and Awajún have already done), because they consider that it is the only way to stop this model of death that we call extractivism. A model that is supported by criminal states with democratic veneers and armed gangs, legal and illegal, that govern the territories of mining, gold extraction, forest clearing and cocaine laboratories.

Previous analyses regarding Peru:

Luis Hernández Navarro: https://chiapas-support.org/2022/12/24/peru-the-language-of-the-street/

Manolo De Los Santos: https://chiapas-support.org/2022/12/15/the-peruvian-oligarchy-overthrew-president-castillo/

Originally Published in Spanish by Desinformemonos, Wednesday, January 11, 2023, https://desinformemonos.org/masacre-en-peru-la-democracia-en-guerra-contra-los-pueblos/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

A lawyer for Indigenous communities and a communal leader disappear in Michoacán

By: Ernesto Martínez, Elio Henríquez, correspondents and Jessica Xantomila, reporter

The lawyer for Indigenous communities Ricardo Arturo Lagunes Gasca and Antonio Díaz Valencia, a teacher and community leader from Aquila, Michoacán, have been missing since January 15, when they returned from an assembly in the Nahua community of Aquila, their relatives and members of human rights organizations reported. The van in which they were traveling appeared with impacts from firearms.

The Office in Mexico of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN-DH), Amnesty International Mexico, the Fray Matías de Córdova Center, the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center and the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba), among others, demanded from the authorities the prompt appearance of the lawyer and the professor alive.

The Frayba, in which Ricardo Lagunes collaborated several years ago, demanded from the Mexican State the prompt appearance of the lawyer and the communal leader alive. In addition, it pointed out that their disappearance “takes place in a context of murders, threats, intimidation, harassment and physical attacks against communities in the region.”

Residents of the Nahua area of Aquila blocked for the second day, every three hours, the bridge on the coastal highway that connects Michoacán with Colima, to demand the search for the lawyer and the professor.

Authorities reported that the day contact with Ricardo and Antonio was lost, on the border between Michoacán and Colima, on the federal highway to Manzanillo, in the area with speed bumps near Cerro de Ortega, municipality of Tecomán, the white pick-up truck in which they were traveling was located, which had bullet impacts.

Lagunes Gasca and Díaz Valencia attended a general assembly in the Nahua community of Aquila, about the renewal of the communal property authorities, which for reasons beyond the control of the 465 community members had been postponed for two years.

Ricardo Lagunes provided legal accompaniment in the indigenous community of Aquila, where there is a lot of mining activity and internal conflicts that are generating serious impacts on the area. In the above photo a community member indicates the iron extraction area of the Ternium Las Encinas mine, which for 10 years has been a focus of conflict because the company intends to reduce royalties for using the land where the deposit is located.

At the end of the meeting, according to the last communication with them, around 6:50 p.m., the lawyer and the activist headed towards Coahuayana to reach the capital of Colima; but they never arrived. “Therefore, it is presumed that Professor Valencia and defender Ricardo Lagunes were deprived of their freedom by unknown persons, a situation that puts their physical integrity and life at serious risk,” says the text signed by their relatives and civil organizations.

Ricardo Lagunes was founder of Asesoría y Defensa Legal del Sureste and has a long national and international career in the defense of collective rights and ejido and communal lands against megaprojects, dispossession and human rights violations, in Chiapas, Oaxaca, Yucatan and Campeche, which has allowed the protection of thousands of hectares of collective lands, of valuable ecosystems and collective rights, especially of indigenous communities.

Guillermo Fernández-Maldonado, representative of the UN-DH in Mexico, said that the disappearance of these two defenders “is a terrible and alarming fact. In this country, defending human rights is an absolutely paramount task, which must be protected. This crime not only undermines the human rights of both defenders, but also seeks to generate fear among those who defend the rights recognized by law.”

The disappearance was reported to the National Search Commission and was registered with folio 1AA67B3D1-8CAF-4A7D-979A-78B786BA141E.

The Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists was also notified, since Lagunes Gasca had precautionary measures; the National Human Rights Commission was also notified.

See also Luis Hernández Navarro’s article on mining and organized crime in the region: https://chiapas-support.org/2020/03/29/santa-maria-ostula-mining-and-organized-crime/

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Wednesday, January 18, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/01/18/estados/027n1est and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee