Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Part One: A DECLARATION…

FOR LIFE

Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés

January 1st, 2021

TO THE PEOPLES OF THE WORLD:

TO PEOPLE FIGHTING IN EUROPE:

BROTHERS, SISTERS AND COMPAÑER@S:

During these previous months, we have established contact between us by various means. We are women, lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender, transvestites, transsexuals, intersex, queer and more, men, groups, collectives, associations, organizations, social movements, indigenous peoples, neighborhood associations, communities and a long etcetera that gives us identity.

We are differentiated and separated by lands, skies, mountains, valleys, steppes, jungles, deserts, oceans, lakes, rivers, streams, lagoons, races, cultures, languages, histories, ages, geographies, sexual and non-sexual identities, roots, borders, forms of organization, social classes, purchasing power, social prestige, fame, popularity, followers, likes, coins, educational level, ways of being, tasks, virtues, defects, pros, cons, buts, howevers, rivalries, enmities, conceptions, arguments, counterarguments, debates, disputes, complaints, accusations, contempt, phobias, philias, praises, repudiations, boos, applauses, divinities, demons, dogmas, heresies, likes, dislikes, ways, and a long etcetera that makes us different and, not infrequently, opposites.

Only very few things unite us:

That we make the pains of the earth our own: violence against women; persecution and contempt of those who are different in their affective, emotional, and sexual identity; annihilation of childhood; genocide against the native peoples; racism; militarism; exploitation; dispossession; the destruction of nature.

The understanding that a system is responsible for these pains. The executioner is an exploitative, patriarchal, pyramidal, racist, thievish and criminal system: capitalism.

The knowledge that it is not possible to reform this system, to educate it, to attenuate it, to soften it, to domesticate it, to humanize it.

The commitment to fight, everywhere and at all times – each and everyone on their own terrain – against this system until we destroy it completely. The survival of humanity depends on the destruction of capitalism. We do not surrender, we do not sell out, and we do not give up.

The certainty that the fight for humanity is global. Just as the ongoing destruction does not recognize borders, nationalities, flags, languages, cultures, races; so the fight for humanity is everywhere, all the time.

The conviction that there are many worlds that live and fight within the world. And that any pretense of homogeneity and hegemony threatens the essence of the human being: freedom. The equality of humanity lies in the respect for difference. In its diversity resides its likeness.

The understanding that what allows us to move forward is not the intention to impose our gaze, our steps, companies, paths and destinations. What allows us to move forward is the listening to and the observation of the Other that, distinct and different, has the same vocation of freedom and justice.

Due to these commonalities, and without abandoning our convictions or ceasing to be who we are, we have agreed:

First – To carry out meetings, dialogues, exchanges of ideas, experiences, analyses and evaluations among those of us who are committed, from different conceptions and from different areas, to the struggle for life. Afterwards, each one will go their own way, or not. Looking and listening to the Other may or may not help us in our steps. But knowing what is different is also part of our struggle and our endeavor, of our humanity.

Second – That these meetings and activities take place on the five continents. That, regarding the European continent, they take place in the months of July, August, September and October of the year 2021, with the direct participation of a Mexican delegation integrated by the CNI-CIG, the Frente de Pueblos en Defensa del Agua y de la Tierra de Morelos, Puebla y Tlaxcala, and the EZLN. And, at later dates to be specified, we will support according to our possibilities the encounters to be carried out in Asia, Africa, Oceania and America.

Third – To invite those who share the same concerns and similar struggles, all honest people and all those belows that rebel and resist in the many corners of the world, to join, contribute, support and participate in these meetings and activities; and to sign and make this statement FOR LIFE their own.

From the bridge of dignity that connects the Europe from Below and to the Left with the mountains of the Mexican Southeast.

We

Planet Earth

January 1, 2021

[Many hundreds, possibly thousands of signatures from around the world can be read on Enlace Zapatista]

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast,

For the women, men, others (otroas), children and elderly of the Zapatista National Liberation Army,

Comandante Don Pablo Contreras and Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés

Mexico

Don Pablo González Casanova (Comandante Don Pablo Contreras)

If you want to sign this Declaration, send your signature to firmasporlavida@ezln.org.mx. Please sign the complete name of your group, collective organization or whatever sea, in your language, and your geography. Signatures will be added as they arrive.

Part Two: The Tavern

Happy 27th Anniversary to the EZLN and Happy New Year to all our readers! Y, Feliz Año!

The calendar? Now. The geography? Any corner of the world.

You don’t quite know why, but you are walking hand in hand with a little girl. You are about to ask her where you are going when you pass in front of a huge tavern. It has a large illuminated sign like a movie theater marquee that reads: “History with a capital ‘H’: Café-bar” and below that, “No women, children, indigenous people, unemployed, people of other genders [otroas], elderly persons, migrants, or other useless people allowed.” A white hand has added: “In this place, Black Lives do not matter[i].” A male hand has scrawled, “Women allowed if they act like men.” Outside the doors of the establishment are heaped cadavers of women of all ages and, judging by their tattered clothes, of all social classes, too. You and the little girl pause, resigned. You peek in the door and see a commotion of men and women, all with masculine mannerisms. A man is standing on the bar with a baseball bat, swinging it threateningly in all directions. The crowd inside is clearly divided: one side is applauding while the other side boos. All of them are drunk, flushed, with furious gazes and drool dripping down their chins.

A man whom you presume is the doorman approaches you and asks:

“You want to come in? You can choose whichever side you like. You want to cheer or boo? It doesn’t matter which you choose, we guarantee you’ll get a lot of followers, likes, thumbs up and applause. You’ll become famous if you come up with something clever, whether in favor or against. And even if you’re not very smart, all you have to do is be loud. It doesn’t matter whether what you say is true or false as long as you make a lot of noise.”

You consider the offer. It sounds attractive, especially now that no one follows you, not even a dog.

“Is it dangerous?” you ask timidly.

The bouncer reassures you: “Not at all, here impunity reigns. Look at the guy who’s up to bat. He says whatever stupid thing and some people applaud him while others criticize him with further idiocies. When he finishes, someone else will take a turn. I already told you that you don’t have to be smart. In fact, here intelligence is an obstacle. Come on in! This is how you forget about all the illnesses, the catastrophes, the misery, the government’s lies, and tomorrow itself. Here, reality doesn’t really matter. What matters is whatever is trendy today.”

You ask: “And what are they debating?”

“Oh, any old thing. Both sides are focused on frivolities and superficialities. Creativity’s not their thing, if you know what I mean,” the bouncer responds as he shoots a fearful glance toward the top of the building.

The girl follows his gaze and points at the top of the building, where you can see a whole floor made of mirrored glass. “And those people up there, are they for or against?” she asks.

“Oh no,” responds the man, and adds in a whisper, “Those are the bar owners. They don’t have to show their faces at all, everyone simply obeys them.”

Outside, further down the path, you see a group of people who, you assume, were not interested in entering the tavern and continued on their way. Another group leaves the establishment with obvious annoyance, murmuring, “It’s impossible to make any sense in there,” and “Instead of ‘History’ it should be called ‘Hysteria.’” They laugh as they walk away.

The girl glances at you. You hesitate…

She tells you, “You can stay here or continue on. Just take responsibility for your decision. Freedom isn’t just the ability to decide what to do and do it. It’s also taking responsibility for what you do and for the decisions you make.”

Still undecided, you ask the girl, “And you, where are you going?” “Home, to my town,” she says, extending her little hands towards the horizon as if to say, “to the world.”

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast

SupGaleano

It’s Mexico, 2020, December, hours before daybreak. It’s cold and the full moon is watching with surprise as the mountains pull themselves together, pick up their naguas [ii] and slowly, very slowly, begin to walk.

-*-

From the Notebook of the Cat-Dog: Esperanza tells Defensa about her dream

“So I’m asleep and I’m dreaming. I know for sure I’m dreaming because I’m asleep. And I see that I’m very far away. There are women and men and others [otroas] who are very other. That is, I don’t know them. They’re speaking a language I don’t know. They are of many colors and have different customs and they’re making quite the racket. They sing and dance, they talk, they argue, they cry and laugh. And nothing I’m seeing is familiar. There are buildings big and small. There are trees and plants similar to the ones that grow here, but different. The food is very other, I mean, everything is very weird. But the strangest thing is that I don’t know why or how, but I know that I’m at home.”

Esperanza waits in silence. Defensa Zapatista finishes taking notes in her notebook, stares at Esperanza for a few seconds and then asks her, “Do you know how to swim?”

I bear witness. Woof-meow.

López Obrador wants the Armed Forces to operate the Maya Train

They would also take charge of new airports, he says

From the Editors

The federal government will seek that the Armed Forces are placed in charge of a State company that will have the objective of heading up the administration and operation of three sections of the Maya Train, of the airports in Chetumal, Palenque and Tulum (soon to start its construction), as well as the Felipe Angeles international air terminal, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador announced yesterday.

From the Tulum archaeological zone, where he and the governors of the region signed the agreement for territorial and urban planning within the framework of the development of work on the Maya Train, the president explained that the objective for the creation of said State company is to protect this work “so that there is no temptation to privatize it,” and further explained that the utilities will be used to finance the pensions and retirements of members of the Army and Navy.

“We will have to define the administration and operation of the train with time. We are thinking about from Tulum to Palenque, which are three sections of the train, plus the airports of Tulum, Chetumal and Palenque, as well as the Felipe Angeles air terminal of Mexico City will be managed by a company that depends on the armed forced in order to achieve good administration of the train and the airports, that it be self-sufficient and that the profits are destined to strengthen finances for their pensioners and retirees,” he indicated.

To guaranty security

Another of the objectives of the projects being administered by the Army and Navy, he added, is: “that we must guaranty security in the region; here we have to be careful that we don’t have any problem of insecurity so that everyone who visits this region is guaranteed that they will be safe.”

In front of the governors of Quintana Roo, Carlos Joaquín González; Yucatán, Mauricio Vila Dosal; of Chiapas, Rutilio Escandón; Tabasco, Adán Augusto López, and Campeche, Carlos Miguel Aysa González, who signed the agreement for territorial and urban planning in the region together with the representative of UN-Habitat Mexico, Eduardo López Moreno, as an honorary witness, the head of the federal Executive explained that all the works in the area represent a joint investment of 200 billion pesos.

The budget includes, in addition to the Maya Train, infrastructure actions for electric and gas energy, remodeling of maritime ports, the Tulum airport, highways and social development for the region.

Recalling that the first phase of vaccination against Covid-19 will begin this month, he pointed out that the advance of this process seeks, in addition to addressing the health issue, the recovery of the tourist influx to levels prior to the pandemic.

Meanwhile, he emphasized, “jobs are generated with this work; it’s as if hotels and infrastructure of another type were being constructed on sections of the Maya Train. A lot of work is taking place and there are going to be even more job opportunities.”

For their part, the five governors of the states through which the Maya Train will pass expressed their willingness to work in a coordinated way on the projects that are profiled as the economic detonator that the Mexican southeast requires.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Monday, December 21, 2020

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/12/21/politica/004n1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

EZLN builds rafts to go to Europe

EZLN builds rafts to go to Europe and ‘share their experience with self-government’

Without Fear: Members of the EZLN assure that they’re not afraid of dying at sea.

By: Isaín Mandujano

TUXTLA GUTIÉRREZ, Chiapas (apro)

Members of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN) began to build and test their first ships for embarking on a trip to Europe in 2021. As predicted, the journey will not be easy, but they have plenty of “strength and lots of ovaries,” the rebel women say.

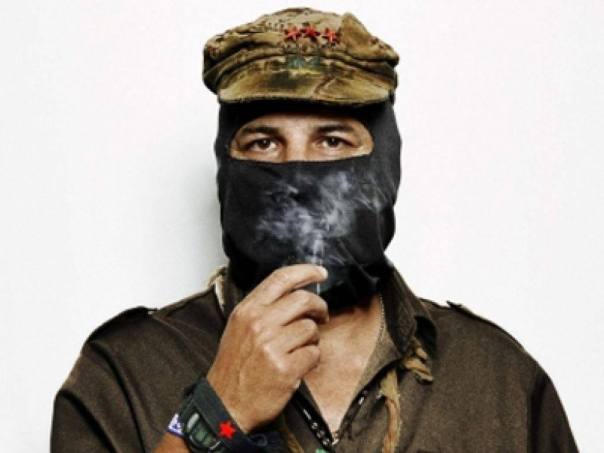

In a communiqué signed by Subcomandante Galeano, accompanied by various videos, he announces the preparations that members of the EZLN are making to undertake this mission.

From the Zapatista Maritime-Terrestrial Training Center in the Lacandón Jungle, “Sup Galeano,” as the EZLN’s spokesperson and political-military leader calls himself, gave the workshop “El Gómito Internacionalista” (The Internationalist Gummy).

In a first video, the indigenous people cut down several trees, built a raft and threw it into a mighty river. On board the raft, a masked man says that they are poor and that they don’t have boats, but they have those rafts, with which they intend to reach Europe.

“We are Zapatistas and we are rebels. We’re not afraid of dying in the water. We are disposed to live and arrive where we have to arrive. We want to participate with the brothers and sisters of other countries. It’s necessary to demonstrate and share our autonomy.”

He pointed out that it’s necessary to share experiences with others, teach them and learn from them, because it’s not only in this region of Mexico that there is misery and many deaths of women and children, it’s also in other countries; that’s why they have proposed throwing themselves into the sea in these rafts and playing with the waves.

With the raft they will go down a river that passes through San Quintín, then they will take the Lacantum River to go to Tenosique, from Tenosique to Tulum and then to Cancun, from where they will depart for Europe, he explained.

In another video, titled “we don’t stop because of ovaries,” a couple of girls approach a river and they ask a man on board a dugout canoe (cayuco) if they are ready for the trip, to which the interlocutor responds that that they are ready and that he is aware that this cayuco is made with wood that doesn’t sink.

He immediately hands them the paddle, and asks them to start practicing. The little girl evaluates that the cayuco turned out very well, but recognizes that it will not be easy, therefore, she says, all the compañeras will have to take turns rowing, and that what the Zapatista women exceed in is “strength and ovaries.”

In another video, they present the creation of the “Zapalancha,” a means of transportation with which they intend to travel to Europe, because many European compañeros and compañeras and those from other countries have already come to learn about the Zapatista struggle in Chiapas and now it’s their turn to undertake the journey to learn about other struggles and other forms of self-government, they pointed out.

Aboard ships, boats, rafts or canoes, men, women and even children will go to arrive in Europe and share their struggle with other rebel struggles. In an animated video they recreated the journey of the “Zapalancha” on the high seas and in another one they presented the crew: some 80 young Zapatista women who are preparing for the mission in the Zapatista Caracol of Morelia and a small yellow-headed parrot called Toti, who will lead the mutiny on board.

In the complete communiqué SupGaleano narrates a story about this crossing. With his metaphorical discourse, the Zapatista leader narrates a dialogue between Defensa Zapatista and Esperanza, a crew member on the trip to Europe.

Extract from the communiqué:

“All right, I’m going to explain something very important to you. But, don’t take notes, just keep it in your head. You might leave the notebook laying around anywhere, but you have to carry your head with you all the time.”

Defensa Zapatista paces back and forth, as she says the late SupMarcos did when he was explaining something very important. Esperanza is seated on a tree trunk and, anticipating, she has placed a plastic tarp over the damp wood, recently blooming with moss, mushrooms and dry twigs.

“You think we’re going to be able to see where the struggle will take us,” Defensa Zapatista blurts out pointing with her little hands to nowhere.

Esperanza is thinking about how to answer, but it’s clear that Defensa asked a rhetorical question, and wasn’t interested in an answer. She was asking a question that led to other questions. According to Defensa Zapatista, she was following the scientific method.

“The problem isn’t getting to the destination, but making a path. That is, if there’s no path, well one has to make it. That’s the only way,” she continued brandishing a machete. Who knows where she got that, I’m sure somebody somewhere is looking for it.

“So, the problem as such has changed and the first thing is the path, because if there’s no path to where you want to go, then that’s your main concern. So what are we going to do if there is no path to where we’re going?”

You can read the complete communiqué in English here.

El comunicado completo en español con videos: http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2020/12/22/tercera-parte-la-mision/

You can donate to support the Zapatistas here:

—————————————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by Proceso

Wednesday, December 23, 2020

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

PART THREE: THE MISSION

By: Subcomandante Galeano

How Defensa Zapatista tried to explain Zapatismo’s mission and other happy reasoning to Esperanza

“All right, I’m going to explain something very important to you. But don’t take notes—just keep it in your head. You might leave the notebook laying around anywhere, but you have to carry your head with you all the time.”

Defensa Zapatista paced back and forth, just like the late SupMarcos used to do when he was explaining something really important. Esperanza was sitting on a tree stump, over which she had wisely placed a piece of plastic tarp to cover the damp wood that was covered in moss, mushrooms, and dry twigs.

“You think we’re going to be able to see where the struggle will take us?” Defensa Zapatista blurted out, gesturing in no particular direction with her little hands.

Esperanza tried to think of how to answer, but it was clear Defensa Zapatista was asking a rhetorical question and wasn’t interested in an answer. She was asking a question that led to other questions. According to Defensa Zapatista, she was following the scientific method.

“The problem isn’t getting to the destination, but making the path. That is, if there is no path, one has to make it. That’s the only way,” she continued, brandishing a machete. Who knows where she got that, I’m sure somebody somewhere is looking for it.

“So the thing is that the problem has changed—the most important thing now is the path. If there is no path to where you want to go, well then that’s your principal concern. So, what do we do if there’s no path to where we want to go?”

Esperanza responds confidently: “We wait until it stops raining so we don’t get wet making the path.”

“No!” Defensa yells, throwing her hands up and clutching her head, ruining the hairdo her mom had spent a half hour fixing.

Esperanza hesitates and then tries again, “I know: we lie to Pedrito and tell him that there’s a bunch of candy where we want to go, but no way to get there, and whoever makes a path the fastest gets all the candy.”

“You think we’re going to ask the men? Hell no! We’re going to do it ourselves as the women that we are,” Defensa responds.

“True,” Esperanza concedes, “plus maybe there will actually be chocolate there.”

Defensa continues, “But what if we get lost as we try to make the path?”

Esperanza responds promptly, “We yell for help? Set off some firecrackers or take the conch shell along so we can call the village to come rescue us?”

Defensa sees that Esperanza is taking the issue quite literally, and worse, getting the approval of everyone gathered around. The cat-dog, for example, is licking his lips imagining the pot of chocolates at the end of the rainbow; the one-eyed horse suspects that there also might be corn with salt and maybe another pot full of plastic bottles; and Calamidad is practicing the choreography designed by SupGaleano called “pas de chocolat,’ which consists of balancing rhinoceros-style over a large pot.

Elías Contreras, meanwhile, had been sharpening his machete on both sides since the very first question.

A little beyond him, an undefined being bearing extraordinary resemblance to a beetle and carrying a sign that reads “call me Ismael,” is debating Old Antonio over the advantages of stasis on dry land, arguing, “Yes indeed my dear Queequeg, no white whale goes near a port.” [i] The old indigenous Zapatista, involuntary teacher of the generation that rose up in arms in 1994, rolls a cigarette and listens attentively to the beetle’s arguments.

Defensa Zapatista assumes that she, just like science and art, is in the difficult position of being misunderstood, like a pas de deux without the embrace to facilitate the pirouettes or the support for a porté; like a film held prisoner in a can, waiting for a gaze to rescue it; like a port without a ship to dock there; like a cumbia awaiting hips to give it action and destination; like a concave Cigala without its convex[ii]; like Luz Casal on her way to meet the flor prometida[iii]; like Louis Lingg without the punk Bombs[iv]; like Panchito Varona looking behind a chord for a stolen April[v]; like a ska without a slam; like praline ice cream without a Sup to do it justice.

But Defensa, being defense and also Zapatista, accepts none of this and, in resistance and rebellion, looks to Old Antonio for assistance.

“Storms respect no one; they hit both sea and land, sky and soil alike. Even the innards of the earth twist and turn with the actions of humans, plants, and animals. Neither color, size, nor ways matter,” Old Antonio says in a low voice.

Everyone falls silent, half out of respect and half out of terror.

Old Antonio continues: “Women and men seek to take shelter from wind, rain, and broken land, waiting for it to pass in order to see what is left. But the earth does more than that; it begins to prepare for what comes next, what comes after. In that process it begins to change; mother earth does not wait for the storm to pass in order to decide what to do, but rather begins to build long before. That is why the wisest ones say that the morning doesn’t just happen, doesn’t appear just like that, but that it lies in wait among the shadows and, for those who know where to look, in the cracks of the night. That is why when the men and women of corn plant their crops, they dream of tortilla, atole, pozol, tamale, and marquesote[vi]. Even though those things are not yet manifest, they know they will come and thus this is what guides their work. They see their field and its fruit before the seed has even touched the soil.”

“When the men and women of corn look at this world and its pain, they also see the world that must be created and they make a path to get there. They have three gazes: one for what came before; one for the present; and one for what is to come. That is how they know that what they are planting is a treasure: the gaze itself.”

Defensa agrees enthusiastically. She understands that Old Antonio understands the argument that she could not explain. Two generations distant in calendars and geographies build a bridge that both comes and goes… just like paths.

“That’s right!” she almost shouts and looks fondly at the old man.

She adds, “If we already know where we want to go, that means we also know where we don’t want to go. So every step we take moves us toward one path and away from another. We haven’t gotten there yet, but the path we walk shows us what our destination will be. If we want to eat tamales, we’re not going to plant squash.”

The whole crowd makes an understandable gesture of disgust, imagining a horrible squash soup.

“We live out the storm however we know how, but we are already preparing what comes next. We prepare it now. That is why we have to take our word far and wide. It doesn’t matter if the person who said it originally isn’t there anymore; rather what matters is that the seed reaches fertile ground and grows. Our word must support others. That is our mission: to be a seed that looks for other seeds,” Defensa Zapatista declares, and looking at Esperanza asks, “Do you understand?”

Esperanza stands up and responds with all the solemnity she can muster at 9 years of age:

“Yes, of course. I have understood that we are all going to die miserably.”

But then she adds immediately, “But we’re going to make it worth it.”

Everyone applauds.

In order to reinforce Esperanza’s “make it worth it,” Old Antonio takes a bag of chocolate “kisses” out of his bag.

The cat-dog downs a good number of them in one gulp, though the one-eyed horse prefers to continue gnawing on its plastic bottle.

Elías Contreras, EZLN investigative commission, repeats in a low voice, “we’re going to make it worth it,” and his heart and thoughts go to brother Samir Flores and those who confront, with dignity as their only weapon, the loud-mouthed thief of water and life who hides behind the weapons of the overseer, who himself blabbers on and on to hide his blind obedience to the true Ruler, which is first, money, then more money, and in the end, still money.[vii] It is never justice, never freedom, and never, ever life.

The beetle begins to talk about how a chocolate bar kept him from dying on the Siberian steppes as he was traveling from the lands of Sami[viii]–where he sang the Yoik[ix]—in Selkup territory[x], to pay tribute to the Cedar, the tree of life. “I went to learn, that’s what journeys are for. There are resistances and rebellions that are no less important and heroic because they are far away,” he says as he uses his many legs to liberate a chocolate from its aluminum foil, applaud, and gulp down a portion of it, all at the same time.

Calamidad, for her part, has understood perfectly well what it means to think about what comes next and with her hands muddied with chocolate, exclaims enthusiastically, “vamos a jugar a las palomitas!”

-*-

From the Zapatista Center for Maritime-Terrestrial Training,

SupGaleano giving a workshop on “Internationalist Vomiting” Mexico, December 2020

From the notebook of the Cat-Dog: The Treasure is the Other

“Upon finishing, he looked at me slowly with his one eye and said, ‘I was waiting for you, Don Durito. Know that I am the last true, living pirate in the world. And I say “true” because now there are an infinite number of “pirates” in financial centers and great government palaces who steal, kill, destroy and loot, without ever touching any water save that of their bathtubs. Here is your mission (he hands me a dossier of old parchments): find the treasure and put it in a safe place. Now, pardon me, but I must die.’ And as he said those words, he let his head fall to the table. Yes, he was dead. The parrot took flight and went out through a window, saying, ‘The exile of Mytilene is dead, dead is the bastard son of Lesbos, dead the pride of the Aegean Sea.[xi] Open your nine doors, fearsome hell, for there the great Red Beard will rest. He has found the one who will follow in his footsteps, and the one who made of the ocean but a tear now sleeps. The pride of true Pirates will now sail with Black Shield.’ Below the window, the Swedish port of Gothenburg spread out, and, in the distance, a nyckelharpa[xii] was weeping . . .”

Don Durito of the Lacandón Jungle. October 1999.[xiii]

Section: Three deliriums, two groups, and a rioter.

(This section consists of Videos in Spanish)

If we follow Admiral Maxo’s route, I think we’d arrive faster by walking over the Bering Strait:

Just try and stop us:

Motor is ready, now just missing… the boat?

First crew:

Second crew: We don’t have the boat yet, but we’ve got the guy who’ll lead the riot onboard (a parrot)

To view the videos: http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2020/12/22/tercera-parte-la-mision/

Translator’s Notes:

[i] The first line of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. Ishmael is the narrator of the book. Queequeg is another character in the book.

[ii] “Concavo y convexo” (Concave and convex) is the title of a love song by Flamenco singer Diego el Cigala.

[iii] “Flor prometida” (Promised flower) is the title track of Spanish pop artist Luz Casal’s seventh studio album.

[iv] Louis Lingg and the Bombs is a French anarchist punk band named in honor of Chicago anarchist Louis Lingg, who was sentenced to death in 1887 for allegedly making the bombs used in the Haymarket Square riot. Lingg committed suicide in prison using an explosive device rather than be executed.

[v] “Quién me ha robado el mes de abril”, (Who stole the month of April from me?) is a song written by renowned Spanish rock music writer and producer Panchito Varona and sung by Spanish songwriter and musician Joaquín Sabina.

[vi] All corn-based food and drink common in southern Mexico.

[vii] This references the struggle of the communities in Morelos resisting the construction of a thermo-electric plant in their region that is part of the “Integrated Plan for Morelos” mega-project. Samir Flores, one of the leaders of the resistance, was killed in February, 2019, in the course of this struggle. The “overseer” refers to Mexican President Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador who backs the megaproject and protects the business interests that would divert water supplies from local communities to the plant.

[viii] The Sami are an indigenous people inhabiting what is now the Northern part of Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia.

[ix] Yoik is a traditional form of song among the Sami people.

[x] The Selkup are an indigenous people whose traditional territory is in central Russia between the Ob and Yenisey rivers. Trees are an important religious symbol for the Selkup, with cedar personifying the world of the dead.

[xi] This passage refers to Barbarossa (Red Beard) who was born in Mytilene on the island of Lesbos in the Aegean Sea and wound up in Constantinople as the Admiral of the Sultan’s fleet.

[xii] A nyckelharpais a traditional Swedish stringed instrument played with a bow and keys that slide under the strings.

[xiii] The excerpt above is from a 1999 communiqué in which Don Durito, the recurring beetle character in EZLN writings, returns from a long voyage to Europe. Translation and footnotes borrowed from “Conversations with Durito.” http://cril.mitotedigital.org/sites/default/files/content/cwdcomplete_0.pdf

——————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by Enlace Zapatista

Monday, December 22, 2020

Original text in Spanish and Videos at:

http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2020/12/22/tercera-parte-la-mision/

Please donate to support the Zapatistas: https://chiapas-support.org/2020/12/23/shelter-in-solidarity-support-the-zapatista-communities/

Shelter in Solidarity: Support the Zapatista Communities

Dear Family & Friends of the Chiapas Support Committee,

WE ARE INVITING YOU TO JOIN US —during one of the most challenging of years— in people-to-people solidarity with the Zapatista communities.

The pandemic provides one of the most revolutionary of opportunities to know and to connect each other’s struggles and communities for justice.

Throughout 2020, the Chiapas Support Committee (CSC) continued bringing you critical information and analyses to understand the Zapatista and Indigenous struggles in Mexico. And we brought people together to connect and to express solidarity and create community in the U.S.

AS THE YEAR ENDS, we are inviting you to join us by sheltering-in-solidarity to break out of the isolation caused by the multi-tiered capitalist crisis called the pandemic. And to reach literally through your device screen, one hand on the keyboard and the other in a fist, that opens, to show solidarity with our sister Zapatista communities in Chiapas.

Join us in contributing generously to express

Solidarity with the Zapatistas

CLICK here to donate—or send your donation through Venmo to @enapoyo1994 | You can also send your donation through snail-mail!

IN 2020, U.S. SOCIAL AND RACIAL JUSTICE STRUGGLES, led by the bold actions and leadership of the Black Lives Matter movement, did not pause in the face of the intertwined capitalist pandemic of racist violence and economic and health crises and a presidency that threatened to undermine the elections and democracy.

In Mexico, the Zapatista and indigenous struggles continued organizing for justice and autonomy despite intensifying paramilitary attacks that are tacitly, if not openly, supported by the Mexican government.

Our struggles for justice and liberation commingle across borders, they are for life to be safe and secure from capitalist misery and exploitation.

Get Ready for 2021 with Anti-Capitalist Solidarity Now

On January 1, 2021, the EZLN (the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, Zapatista National Liberation Army) will celebrate the 27th anniversary of its uprising, when Indigenous communities said NO to the capitalist death sentence of “free” trade being imposed on Indigenous people everywhere.

In 2020, the Zapatistas continued to steadily build their projects of land justice and autonomy while facing one of the largest and most widespread paramilitary offensives in many years. The paramilitaries were given impunity by the “progressive” government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), the government of Chiapas and of various municipalities in the state.

The paramilitary attacks are part of a broader war of attrition against the Zapatista Indigenous autonomous territories being carried out by the Mexican government. This serves the interests of the Mexican government as it continues the capitalist goal of dispossessing and destroying the EZLN and its support bases. At the same time, the Zapatistas are coping with the coronavirus pandemic.

While AMLO was still downplaying the pandemic and encouraging people not to social distance, the EZLN declared a Red Alert on March 16, closed its communities to outsiders, started making masks and practicing social distancing. Around the same time, an agrarian conflict between Chenalhó and Aldama heated up. Paramilitary groups in Chenalhó began firing high-caliber weapons across a ravine into the Aldama communities.

The paramilitaries have forcibly displaced approximately 3,000 Maya Tsotsils in the Aldama municipality, mostly women and children, and another thousand in the nearby Chalchihuitán municipality. The health and wellbeing of the displaced communities has been severely undermined. They have been suffering from famine, unable to cultivate and harvest their crops, living at the mercy of the natural elements.

In August, a paramilitary group known by its acronym of ORCAO robbed and set fires to coffee warehouses and a roadside community diner at the Cuxuljá Crossroads, which is owned and operated by the Zapatistas in the Moisés Gandhi community, autonomous municipality of Lucio Cabañas.

A SOLIDARITY CARAVAN WENT TO Moisés Gandhi to observe and document the human rights abuses that ORCAO paramilitaries were inflicting on that Zapatista community: land invasions, destroying crops, homes, cooperatives and electrical and water infrastructure, as well as shootings and robberies.

The caravan documented continuous paramilitary attacks on Zapatistas in the Moisés Gandhi region. To date, the economic damage to Moisés Gandhi totals $1,456,021 pesos, a daunting sum for a community of subsistence farmers. The most recent publicized attack was the kidnapping and torture of a Moisés Gandhi resident in November. He was released to human rights workers after several days.

And it’s not only Zapatista communities under attack.

Indigenous communities, members of the Congreso Nacional Indígena (CNI, Indigenous National Congress) in Chilón, Tila and San Sebastián Bachajón, have also suffered paramilitary attacks and police repression.

It is against this backdrop of struggles that we are inviting you to join us with a contributionthat will help us send a message of solidarity to the Zapatista and Indigenous communities and a repudiation of the Mexican government’s role in the paramilitary attacks.

Zapatismo 2020 in the U.S.

FOR THE CHIAPAS SUPPORT COMMITTEE, 2020 began with a burst of organizing energy that has not stopped

In March, the Chiapas Support Committee helped host in Oakland the first Encuentro (gathering) of the Sexta Grietas del Norte, a network of individuals and groups that adhere to the EZLN’s Sixth Lancandón Declaration.

The Encuentro brought together Zapatista supporters to Oakland the weekend before the pandemic shut down everything. Over 100 activists, students and academics from California and other parts of the U.S. participated in the Zapatista gathering. Participants strategized on the work of solidarity and learned from each other about the Zapatista and Indigenous peoples struggles in Mexico.

When the gathering closed with a traditional circle, where everyone greeted each other and said their goodbyes person-to-person, no one knew the organizing challenges that the pandemic would bring. What was certain was that the Chiapas Support Committee and the Sexta Grietas would continue its ant-like work of building solidarity with the Zapatista communities, sharing information, analyses and updates and organizing solidarity actions.

Sheltering In Solidarity

In 2020, the Chiapas Support Committee:

- Continued publishing its Compañero Manuel blog and held several online forums and actions. We continued reaching thousands of activists and organizers through the CSC’s Facebook page and our blog.

- Organized in June an emergency fundraiser and in September organized an action to support Zapatista and Indigenous communities facing famine and denounced the Mexican government-supported paramilitary attacks, which have resulted in loss of life and pillaging of entire communities. The paramilitary attacks have forced hundreds of Indigenous people to flee for their lives, caused famine, and the attacks have not diminished.

- In July, launched the new monthly online ¡Viva Zapata! Film Series, viewing films on the Zapatista and other third world revolutionary movements, with after-screening discussions with dozens of participants.

- Held our annual CompArte gathering. We called CompArte 2020, “Sheltering in Art, Solidarity & Resistance” and held it during three online sessions on the 26th of August, September and October. The 26th day was chosen to commemorate the twenty-sixth anniversary of the EZLN 1994 uprising. Dozens of participants shared their art and visions and together learned about Zapatismo and art-struggle. And,

- Relaunched its educational workshop, “Waffles & Zapatismo,” in its first online edition on November 17—the date commemorating the 37th anniversary of the founding of the EZLN. Participants heard from a panel of speakers focusing on the roots of the EZLN and its history leading up to the January 1, 1994 uprising. And,

- Collaborated with community groups on a film-showing on Women and Autonomy. The CSC and partners gathered in an outdoor space with social distancing, enjoying community with music and Zapatista-related films and discussion (in person and via zoom) with the filmmakers.

All your and our contributions will go to support the Zapatista communities’ projects building autonomy. The Chiapas Support Committee is an all-volunteer organization whose members absorb/pay for the costs of the educational work we do.

Creating paths to stay in relationship

for justice & liberation

On March 16, the EZLN issued a “red alert” communique calling on all Zapatista communities to close and shelter-in to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

RECOGNIZING THE EMERGING CHALLENGES brought on by the pandemic, the EZLN said:

. . . We call for human contact not to be lost, but to temporarily change the ways to know ourselves, compañeros, compañeras, compañeroas, sisters and brothers.

The word and the ear, along with the heart, have many paths, many ways, many calendars, and many geographies to find each other. And this fight for life can be one of them.

Because of Coronavirus, the EZLN Closes the Caracoles and Calls to not Abandon Current Struggles

The Chiapas Support Committee continues working hard to nurture the human connection, even as COVID-19 has worsened the cruel race, gender and class inequities under capitalism.

The pandemic has hit people of color and Indigenous communities everywhere particularly hard—in the U.S. and in Mexico.

YOUR SOLIDARITY, WITH OURS, will be more powerful and can pierce the silence by donating generously to support Zapatista projects of autonomy and self-governance.

The year 2020 has made solidarity with Indigenous struggles more urgent and a cornerstone of movements for deep racial justice in the U.S.

We invite you to join us in solidarity and make a generous contribution to connect with the Zapatista communities by sheltering-in-solidarity!

Here are two ways to show anti-Capitalist solidarity

with the Zapatistas

- Make a generous donation here —or through Venmo, @Enapoyo1994

- Or make a unique donation to acquire a piece of Zapatista artesanía, click here.

- Let’s find ways together to connect and to raise a multitude of voices and struggles for justice and liberation in 2021. Subscribe to our e-newsletter and work with us in our different actions of solidarity with the Zapatistas!

THE MEMBERS of the Board of the Chiapas Support Committee thank you with an open heart and a tightly closed fist raised for justice and liberation.

STAY CONNECTED WITH US!

Subscribe to our E-newsletter here

Read the CSC’s Compañero Manuel Blog

Visit our CSC Facebook page

Follow our Instagram page @compartezapatistaContact us through email:enapoyo1994@yahoo.com

Chiapas Support Committee

P.O. Box 3421

Oakland, CA 94609

www.chiapas-support.org

The terror in Chiapas communities doesn’t stop: Red TDT

By: Elio Henríquez

San Cristóbal De Las Casas, Chiapas

Upon concluding a three-day tour through communities of the North, Highlands and Coast of Chiapas, members of the Civil Observation Mission, composed of organizations belonging to the All Rights for Everyone National Network of Civilian Human Rights Organisms (Red Nacional de Organismos Civiles de Derechos Humanos Todos los Derechos para Todas y Todos, Red TDT), reported that they witnessed: “critical situations that violate fundamental rights, with a worrisome lack of will and empathy of the authorities.”

At a press conference in the offices of the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba), in the context of the commemoration of International Human Rights Day, they showed their concern “for the circumstances of systematic and structural violations of civil rights that we have been able to document in the three regions.”

They explained that the 38 members of the mission visited communities in Chalchihuitán, Acteal, Aldama, Nuevo San Gregorio, Moisés Gandhi, Chilón and Tonalá from December 7-10, where they listened to stories of people affected by forced displacement, dispossession of land, arbitrary arrest, torture, harassment, threats and criminalization, among other aggressions.

They also met with authorities from the three levels of government to find out about the follow-up. The Frayba’s director, Pedro Faro, emphasized that: “the situation of terror and hell that inhabitants of 13 Aldama communities experience nonstop; they are attacked by paramilitary-style armed groups” in Santa Martha, Chenalhó. “We still received reports of new attacks on Wednesday.”

He considered that the agreement signed on November 27 by both towns: “is hilarious and a mockery because the attacks continue,” while at the same time ensuring that the authorities at all three levels “know from which parts (of Santa Martha) the gunshots are coming, but they have not disarticulated the hostile groups so that the violence ends completely.”

He maintained that: “the absence of State presence has caused an increase in the criminal acts of members of the Regional Organization of Ocosingo Coffee Growers (Orcao) against Zapatista support bases in the autonomous localities of Moisés Gandhi and San Gregorio, located in the official municipality of Ocosingo.

“We are indignant, outraged and angry because, despite the calls of international organizations, the Mexican State is acting at half gas. The fourth transformation is one of high simulation, with a discourse that doesn’t correspond to the facts.” In addition to the TDT Network (made up of 86 organizations from 23 states), 14 national groupings participated. Members of Doctors of the World, International Service for Peace and the Swedish Movement for Reconciliation accompanied them.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Friday, December 11, 2020

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/12/11/politica/006n1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The Maya Train is leveling in Palenque

The home of María Antonia and her husband is next to the Maya Train tracks. Photo: Angeles Mariscal

By: Ángeles Mariscal

Palenque, Chiapas.

“Right of way” became the words most feared by the residents who are settled along the 232 kilometers of what is known as the First Section of the Maya Train (Tren Maya). Those words are leaving a trail in their wake.

For Maria Antonia Vázquez and her husband, two elderly people over 60, those words not only mean that the water pipes that supply their house collapsed when a bulldozer broke them, and that piles of earth now make it difficult to exit their home located in Ejido Guadalupe, located a few kilometers from the city of Palenque.

Those words also mean that the main wall of their house is going to be torn down, that they are going to lose a part of their kitchen and that the bathroom and septic tank will disappear. Because, technically, the house that they have inhabited for more than two decades, is within the train’s “right of way,” a right that passes over their own rights.

Now, Maria Antonia says, they don’t sleep thinking that “the money that the engineer told us they were going to pay to be able to build our house in another place, has not arrived. And at any moment the machines can pass by and throw all this at us.”

The elderly woman and her husband don’t have any document that allows them to be certain that they will be compensated, because in these places, the Barrientos and Associates Law Office, -the company hired by the National Fund for Tourism Promotion (Fonatur) to “free the right of way,” by acquiring or vacating the land required for work on the Maya Train- has only made oral agreements. And those who have signed an indemnification agreement were not given any proof.

Since the work started last June, María Antonia and her neighbors wake up with the same uncertainty, listening to how bulldozers are knocking down trees and any obstacle to what the government of Mexico presents as a project that: “is going to detonate economic growth and social development.”

For Gregori Mendoza Mendoza, an indigenous man of the Chol ethnicity, the “right of way” not only took a few meters away from the place where his home is located; now, he and his family could lose their entire house because a part of the ejido will be at an end where the Maya Train is expected to pass at a speed of 160 kilometers per hour. This implies that in order for the residents to be able to cross from one side to the other, a uneven bridge would be built, which would pass right where their house is.

“The engineer showed us the plan, he said that the bridge will pass 18 meters inside the land where my house is. After that, they haven’t told us anything else, they haven’t explained anything to us, but my family and I are no longer at peace,” he explains while excavators and trucks are parked outside his house removing thousands of tons of earth.

What happens to Gregori Mendoza and his family is what the authorities call “collateral damage,” about which they do not speak clearly .

The same damages will be to thousands of campesinos and livestock owners, because upon erecting fences or walls along the train’s route, the transit paths of the animals that give them sustenance will be cut off.

Homero Cambrano, of Ranchería San Marcos, remembers that he was one of the people who took to the Maya Train project. “I told them that this was going to be for the good of the community, but now I no longer think the same way.”

“Right now they want us to seek alternative paths, because the Maya Train is going to pass, they already put in the work and cut off our passes. If we don’t have passage for moving cattle, we have to travel at least a kilometer and a half to cross from one corral to another.”

He also explains that these “cut offs of passes” affect “armadillos, monkeys, iguanas and even snakes” that have their established habitat. He asks: “Do these people think that the animals are also going to cross over the bridges?”

The price of land

José Luis León is the coordinator of Section 1 of the Maya Train project; he is in charge of the Barrientos and Associates Law Firm to “free the right of way” that goes from Palenque to Escárcega, Campeche. He is known as “the engineer” in the region.

For him, the work is advancing “in accordance with law (…) practically without any obstacle, without major setbacks.” He is the one in charge of negotiating with residents of the Guadalupe, Chakamax, Estrella de Belén and El Jibarito ejidos in Chiapas; and with around 200 property owners in this same state.

He is also responsible for negotiating with the Pénjamo, Reforma Independencia, Tenosique 3rd Section, El Águila, El Último Esfuerzo ejidos and Barí, in Tabasco; and El Naranjito, Candelaria, Pejelarto, among others in Campeche.

His perception about the process that he heads is different than the perception of the Guadalupe ejido owners. The ejido owners, for example, calculate that they will lose some 10 hectares of their land because of this work, and that a square meter of this land is worth about 200 pesos. Meanwhile, they also ask to repair the “collateral damage,” a just indemnification for the loss of those lands.

The tone of the negotiations that he heads was placed on the table at the ejido assembly last November 22. There, Doris Ethel de Atocha Cámara Sánchez, who introduces herself as “the one in charge of monitoring the social part” on behalf of FONATUR, told the campesinos that they have no right to this land, because the train tracks were built before the town will be registered with the Agrarian Registry, and that any payment given to them is an act of consideration. “Railroads were first (to arrive in the zone more than 40 years ago), while their town wasn’t registered legally until 1996. Thus, there would be no reason to indemnify the ejido; but, because the president made a promise to support the southeast in order to get them out of the backwardness, he’s going to give this support to the ejido,” she told them during the meeting.

The “support” for the ejido, she explained, is that the only impact that will be recognized due to work on the Maya Train, is a little more than 3 hectares, whose official assigned value is 12 pesos per square meter, “but, due to being in a special situation, they will be paid at 32 pesos per square meter,” explained the officials from FONATUR and the Barrientos and Associates Law Firm.

José Luis León, justifies the appraisal they make of this land located in one of the ecosystems with the greatest biodiversity on the planet, pointing out that the price given is “based on an appraisal provided by FONATUR, and carried out by the Institute of Administration and Appraisals of National Assets. We do not set the values, a specialist in the matter does it. We are not able to make payments that are not guaranteed by the institution in charge. They are commercial appraisals, because there are lands here that are worth 8 pesos per square meter.”

Ángel Palomeque de la Cruz, one of the ejido owners who also lost part of his home due to this project, explains why the appraisal they have on their land is unfair: “here, 500 meters from the ejido, the price at which we can acquire a new plot of 200 square meters is from 80 to 100 thousand pesos; iin other words, each square meter is worth 400 pesos. Why then do they only want to pay us 12 pesos, or 32 pesos? Are we worth less? What are we going to be able to buy with that amount of money?”

The uncertainty

Inhabitants of the Guadalupe ejido are not the only ones in these first kilometers who have questioned the impact that the Maya Train is leaving. Right at the entry gate of the first section, between kilometer zero and six, is the Barrio Los Olvidados, which according to the diagnosis of the MarketDataMéxico Inteligencia Comercial “has an estimated economic output of 260 million annually.”

“Additionally, it is estimated that 800 people work in the district, bringing the total number of residents and workers to 3,000. There are some 150 commercial establishments in operation Barrio Los Olvidados district,” the website details.

The first Maya Train station will be located in one part of this neighborhood, and a significant number of families will have to leave. At the moment they are not sure about who has to leave; the information has not been clear ot transparent for them. José Luis León is aware of that.

“People have uncertainty about knowing what’s going to happen to them. The federal government is making the diagnosis to be able to give an alternative solution, call it relocation or call it something else. There are people there who have houses, others made of wood or sheet metal…”. He explains that, for now, the work has not started there.

However, residents of Barrio Los Olvidados who are in “the right of way” already envision themselves as a displaced population, and have insistently asked to be heard.

The Union of Those Displaced by the Maya Train protests in Palenque with a banner that asks to be relocated. Photo: Angeles Mariscal

“Mr. President AMLO, we are vulnerable families and we saw ourselves in need of living on the right of way. We ask you to listen to us, FONATUR is arrogance and intimidation to throw us out,” they explain on a canvas that they are unfolding at events where public officials congregate.

The transporters who own cargo trucks in Palenque are also asking to be heard. They assure that one of the federal government’s promises was to give them work from the start of the project, a promise that has not materialized.

Elin Ramírez Betancur, a representative for the truckers, details that the local workforce has been ignored, and the companies that won the bidding have hired people from other states.

In order to hire Palenque workers, he explains, they required them to join the CATEM labor union, and set the cost of their service at more than 70 percent less than the commercial price. Elin details that the payment for a load of cargo material is valued at 2, 700 pesos, “and they want to pay us at 800 pesos.”

“The government practically left us in the hands of the Mota-Engil company, which won the bid for construction of the first section, and the authorities have not wanted to listen to us,” it laments.

Work on the Maya Train in this region started last June, in the midst of the strongest stage of the pandemic; in just five months, the impacts and disagreement in the communities are adding up.

Although just last November 26, the general director of FONATUR, Rogelio Jiménez Pons, insisted during a conference with students, that “the Maya Train will generate new development scenarios (…) and will permit improving the quality of life of the inhabitants.”

That’s not a coincidence. What happens among those who inhabit the first kilometers of the project is proof of that.

Last November 20, a letter was made public from six United Nations human rights special relators, sent to the Mexican government. In it they point to a series of human rights violations committed against people who live in the region through which the Maya Train will pass.

——————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo

Monday, November 30, 2020

https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/2020/11/el-tren-maya-va-arrasando/

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Indigenous collectives win definitive suspension of Maya Train work

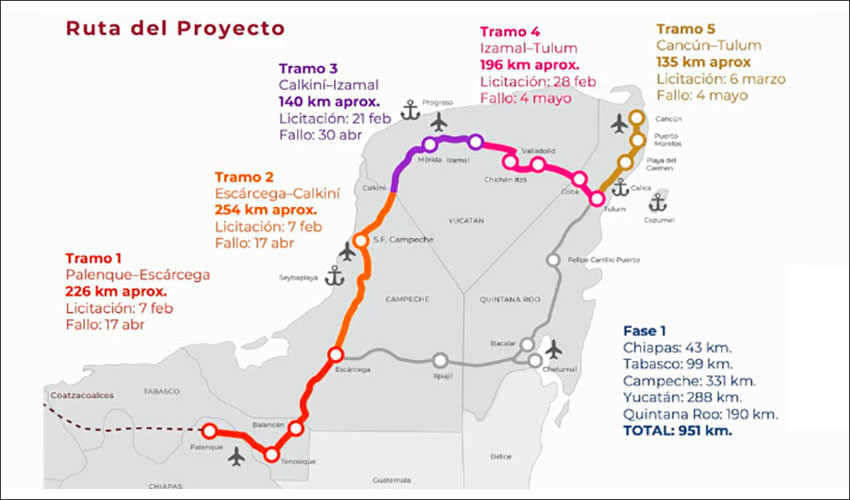

The map shows all of Phase 1 of the Maya Train route with its 5 sections. “Tramo 2” on the map is the Section 2 protected by the court order.

By: Angélica Enciso L.

The first district court of Campeche granted a definitive suspension regarding the construction of new work on Section 2 of the Maya Train, from Escárcega to Calkini, [1] in Campeche, to the region’s indigenous communities and the Mexican Center for Environmental Law (Cemda). With this resolution, those who filed the request for protection (amparo) can celebrate a legal process that prohibits work being carried out that causes irreparable damage to the environment.

Collectives from Campeche and Quintana Roo explained in a videoconference that the human right of access to a healthy environment is violated with these projects, since there is information that not just the railroad, but also the big development poles will generate great social and environmental impacts.

They indicated that the effects of the environmental assessment have not been presented in their entirety, because they fragment them so that the consequences they will have cannot be visualized; it also promotes speculation about the value of land.

Xavier Martínez, operations director of the Cemda, stated that it was incorrect for the Maya Train project to be divided for evaluation, since the environmental impact assessment (EIA) must be comprehensive to foresee global impacts; “the Semarnat [2] did not evaluate the project as a whole,” he accused.

This definitive suspension is related to the request for protection (amparo) filed in July 2020 against the Maya Train project. In addition, it affects Phase 1 of the Maya Train, whose EIA was authorized last week; they won’t be able to carry out work on Phase 1 because it would be dealing with new work on Section 2 from Escárcega to Calkini.

[1] The distance from Escárcega to Calkini is a long stretch from southern Campeche state to its northern border with the state of Yucatán. Old tracks already exist along this stretch of the Maya Train. The court’s decision does not stop repair and maintenance work on the existing tracks; it stops new work, which is significant.

[2] Semarnat is Mexico’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Tuesday, December 8, 2020

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/12/08/politica/013n1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Critical thought and the pandemic

By: Raúl Zibechi

By: Raúl Zibechi

One of the main characteristics of critical thought has been its uneasiness, its capacity to disturb the common places, to question established knowledge and shake off the drowsiness of inertia. It was always thinking that went against the tide, rebellious and insubordinate.

Marx dedicated himself to turning Hegel’s theoretical legacy upside down. Lenin was determined to disobey Marx, who assured that the revolution would win in the most industrially advanced countries. Mao and the Vietnamese rejected the urban insurrections for the prolonged peasant war. Fidel and Che were heretics with respect to the communist parties that dominated the stage of the left.

The much-praised Walter Benjamin was relentless with the idea of progress and, more recently, environmentalists question development, while feminists reject vertical organizations and patriarchal warlords.

The EZLN, for its part, reaps the successes and avoids the errors of previous revolutions, consequently setting aside war in order to continue transforming the world and defending (by all means) the territories where the people rule by exercising their autonomy.

In what situation is critical thought in the midst of a pandemic? What should be the central points of its analysis? Who is formulating it in this period?

I will try to answer in a few lines.

The first is that established thought, articulated by academia, parties and intellectual authorities, is in the midst of decline, a process entangled with the ongoing civilizational and systemic crisis. Perhaps for being part of a modern, urban, western colonial and patriarchal civilization. That is, for having surrendered to capitalism.

The bulk of the so-called intellectuals dedicate themselves to justifying the errors and horrors of the parties of the electoral left, rather than criticizing them, with the sad argument that they don’t want to favor the right. If criticizing the left were that, Marx and Lenin would have been dismissed as right-wingers, as they dedicated some of their best works to questioning their comrades-in-arms.

The second is that critical thought should remove the veil from the structural and long-term causes of the situation we are living in. Not entertaining audiences with fallacious arguments. To be able to link the pandemic with the neoliberal extractive model, the brutal financial speculations, and the 4th world war against the people, instead of attributing the failures or the successes in combating the virus to this or that government. This is what I call entertaining instead of analyzing.

Moreover, critical thinking should not be satisfied with diagnoses. We are overwhelmed by judgements of the most diverse kind, many of them contradictory. Years ago, peak oil was mentioned as the vault key to the end of capitalist civilization. Much earlier, it was assured that the system would fall victim to inexorable economic laws.

Every day, there are diagnostics that place the limits of the system on the environment, the depletion of resources, and a long list of supposed objective causes that do nothing more than elude social conflict as the only way to put a stop to and defeat capitalism. Benjamin already said it: if the system were going to fall for objective reasons, the struggle wouldn’t make the least bit of sense.

The third seems to me the most important. Until today, those in charge of expressing critical thinking were academic, upper-middle class white men. Of course the kinds of ideas that they shared were Eurocentric, patriarchal, and colonial, although it should be acknowledged that they weren’t all wrong because of this. We just have to pass them through the sieve of the people, the women and the children.

Now those who are issuing critical thought are no longer individuals, but peoples, collectives, communities, organizations, and movements. Who are the theoretical representatives of the Mapuche people or the indigenous peoples of the Colombian Cauca region? Who embodies the ideas of the feminist and the anti-patriarchal women’s movements?

There are still those who believe that Zapatista thinking was a work of Subcomandante Marcos and now Subcomandante Galeano. They will never accept that they are thoughts born of collective experience that are communicated by elected spokespeople below. They will never accept that the current spokesperson is Subcomandante Moíses.

This is the reality of the current critical thinking. Detours above, creativity below. Like life itself. There is nothing essentialist about this. Living knowledge arises among those who struggle. Only those who are changing the world can know it in depth, among other things because they’re going through life that way, because they can’t have any illusions about those above, much less the political colors and discourse that they broadcast.

Benjamin said it with absolute clarity: The subject of historical knowledge is the oppressed class itself, when it fights.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Friday, December 4, 2020

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/12/04/opinion/026a1pol

Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee with English interpretation by Schools for Chiapas