Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Background: Conquest, national independence and indigenous emancipation [On internal colonialism]

By Francisco López Bárcenas

This year marks 500 years since the fall of Tenochtitlan to the power of the Spanish invaders. That event initiated the conquest and subsequent colonization of all of Anahuac, the part of the continent known as Central America and Aridoamerica, the territory that now makes up the Mexican State. Maybe it was thinking of this that two days before 2020 ended, the Diario Oficial de la Federación [The Federation’s Official Daily] published a decree made by the Congress of the Union declaring this current year the Year of Independence. Because these events are bound together, various academic institutions announced plans to analyze the impact that the conquest, colonization and struggles for independence continue to have on the life of its inhabitants, but most of all, on the indigenous peoples that live in the country.

This issue is important, most of all given new interpretations that we have of these events, which are the product of historical findings and because of the structures that maintain exploitation in recent years. Since the mid 20th century, studies began to appear that contradicted the way that the history of the conquest was officially told and that question the way in which the war of independence unfolded, but most of all, they question the outcomes of that war. This was how we knew that the conquest was made possible by the superiority of Spanish weapons, but also by the cooperation of some Indigenous groups who thought that they would be liberated from their rivals, which they were, but only to fall into a much more profound subordination, which was not only economic, political and military, but also cultural, religious, and epistemic. Spanish domination was both spiritual and material.

And more has been discovered about independence: The new interpretations discuss how national independence didn’t represent an independence for indigenous peoples, who in those times made up the majority population. These studies explain that the State that emerged when New Spain separated from the Spanish crown maintained the same colonial structures that were built over 300 years. The only difference was that now the colonizers were Criollos [Spanish people born in Mexico], and the colonized were the indigenous. They explained the dispossession of Indigenous lands, forests and water over the second half of the 19th century, which led to their armed confrontation with the State to ensure their existence. The studies talk of a second colonization, which persists. Many respected academics referred to the phenomenon as an internal colonization, with different stages and expressions.

Contrary to popular belief, indigenismo [indigenism] was part of these politics of internal colonization and multiculturalism was its neoliberal version. It is important to have this in mind, especially when thinking about the emancipation of peoples fighting for their autonomy. Many indigenous weren’t completely aware of this during the indigenismo movement. This led them to accept positions in the colonizing government, thinking that in this way they were contributing to the emancipation of their people, when, to the contrary, they attained personal prestige and a better financial and social position for themselves. In exchange they helped construct a discourse that concealed the dispossession of their people and concealed the repression of anyone who was in opposition. Those who buy into the “Fourth Transformation” do the same: They are silent when the rights of Indigenous people are violated, or worse, they say that their rights are respected.

To shed light and find the horizon on the road to emancipation that we are to walk moving forward, it is good to enter the debate taking in mind the perspective and conditions of the people. There are issues that require explanation: What are the specific characteristics of internal colonialism in a government that said it was about transformation, but at the heart maintains the same politics as its predecessors? What effect does intercultural education have on either maintaining or rising above the colonization of knowledge? Do the paths to political participation created by the Mexican government lead towards emancipation or to the continuation of internal colonization? Do the forms of community production serve as emancipatory processes on the regional or national level, or do they just function in some localities? And, most importantly, are we building roads towards emancipation, or just towards resistance?

——————————————————————

Originally appeared in Spanish, published by La Jornada, as “Conquista, independencia nacional y emancipación indigena.” Translated to English by the Chiapas Support Committee. Read the original here: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2021/01/20/opinion/016a1pol

In the above mentioned decree from the Congress, declaring 2021 the Year of Independence, the executive powers are instructed to create a program with activities to commemorate it. The organizations of indigenous people and their allies could do the same from their specific perspective: searching for concrete solutions to real problems. The ideological struggle is also important in the creation of the road to emancipation.

CNI warns of the country’s reorganization against the indigenous peoples

Before the pandemic, this was the CNI march on the anniversary of the death of Samir Flores, a Nahua from Amilcingo, Morelos who defended his territory from the Morelos Integral Project.

By: Daliri Oropeza

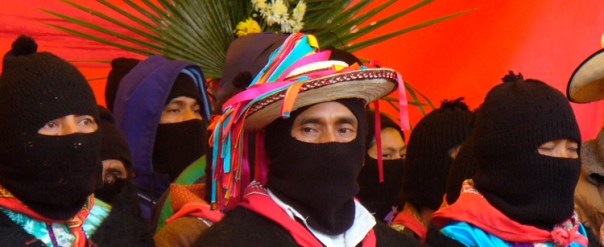

The National Indigenous Congress decided in an assembly to accompany the EZLN’s tour to different continents and to go on the offensive faced with the political landscape that is pushing energy megaprojects and imposing a territorial reorganization focused on profits.

“Now we are on the offensive,” a Nahua campesino delegate of the National Indigenous Congress tells me, who, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic attended the Fifth Joint Assembly with the Indigenous Government Council. It was a two-day meeting with 180 participants; representing most of the peoples that make up this network of peoples, communities and barrios.

Once there, the social barriers that Covid-19 has created were broken. The meeting was held in a recuperated territory in the Ejido Tepoztlán, Morelos, the Fifth Stone. It was taken back (recuperated) from the first one to plunder it, with the surname of Salinas de Gortari. [1] Only two representatives from each people were allowed to be present.

Many people felt nervous at the beginning because of the pandemic. Little by little the atmosphere normalized with the mutual care of following health measures and the use of masks. The EZLN’s invitation to accompany the tour through various continents and the crisis situation in which we live, which is much more acute in the communities in resistance, forced the CNI to leave the virtual world and make agreements face to face.

Morelos is in the red zone for Covid. And also for the megaprojects. For this reason, it was symbolic that they carried out these collective decisions in Tepoztlán. There the government of the self-proclaimed 4T is the Huexca Thermoelectric Plant and with it, the culmination of the Morelos Integral Project.

“The anti-capitalist proposal has body and substance,” affirms Carlos González, agrarian lawyer and delegate to the CNI.

In the pronouncement they denounce:

“The imposition of the Maya Train, coupled with the construction of 15 urban centers, of the Salina Cruz-Coatzacoalcos Interoceanic Corridor that contemplates 10 urban-industrial corridors, and of the International Airport of Mexico City-Lake Texcoco Ecological Park, together with the Morelos Integral Project seek the country’s reorganization in accordance with the economic interests of big capital. Similarly, this project of building for the benefit of foreign companies three thermoelectric plants –one of which is finished–, a network of pipelines and a mega-plant to store fuels in the Santiago River watershed, to the south of Guadalara, which also happens to be one of the most contaminated regions in the country, is very serious; to all of that you have to add the Centenary Canal, currently being carried out by the National Guard, which intends to draw from the San Pedro and Santiago Rivers in Nayarit. In the same way, open pit mining threatens hundreds of territories of indigenous peoples using the same formula of division, dispossession and destruction of our communities.”

“Capitalism in its incessant development is driving human societies to madness, it is propitiating the destruction of the conditions for human life, as we have already indicated during the tour of the compañera Marichuy with the Indigenous Governing Council and the Zapatistas over and over again,” assures Carlos González, and he emphasizes that it is one of the core points in the collective reflection of the Fifth Assembly, in an interview with journalist Rubén Martín.

This crack that the Zapatistas open to denounce the dispossession is important.

In the five working groups, as well as in the plenary session, the CNI decided that a commission made up of mostly women would attend the tour alongside the EZLN across 5 continents. And not only that. They agreed to incorporate a commission of care for the families that stay behind while the women heed the call.

Accordion to the sociologist and social anthropologist Márgara Millán, who also attended the Fifth Assembly, this is a qualitative advancement in the CNI’s way of organizing. To assume care in a collective way is a result of their lived experience during the tour of Marichuy, in addition to the imprint made by the Zapatista women that have led fundamental organizational gatherings.

What Millán refers to as advances, the Nahua campesino of the CNI expresses as going on the offensive, through activating care. It is care for the countryside, care for the compañeras that predominates the discussions. It is not only denouncing, but acting. To subscribe to the Zapatista initiative for life is to participate in the activities and deepen the anticapitalist struggles of resistance.

[1] Carlos Salinas de Gortari was president of Mexico between 1988 and 1994, notably during the Zapatista Uprising.

—————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by Pie de Página

Wednesday, February 3, 2021

https://piedepagina.mx/cni-advierte-reordenamiento-del-pais-en-contra-de-los-pueblos-indigenas/

English interpretation by Schools for Chiapas

Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

The February betrayal, a sign of the war that continues

By: Pedro Faro Navarro*

It wasn’t the EZLN that broke the dialogue and re-started the war.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that feigned political will while it prepared the military and treacherous blow.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that invented a conspiracy to obtain reasons that justify the irrational.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that detained and tortured civilians.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that murdered.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that bombed and machine-gunned populations.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that raped indigenous women.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that stole from and dispossessed campesinos.

It was the government.

It wasn’t the EZLN that betrayed the will of the whole nation, of achieving a political exit to the conflict.

It was the government.

Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos

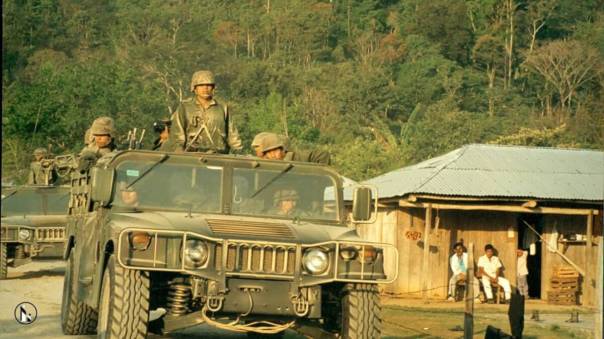

February 9 marked the 26th anniversary of the federal government’s betrayal, Ernesto Zedillo, the president of Mexico’s betrayal of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN), the betrayal of an entire nation that demanded peace and the response from the State was the activation of the Chiapas 94 Counterinsurgency Plan.

This action took place in the context of the distention to the internal armed conflict and reactivation of the dialogue. The Mexican government showed its most faithful face, repression of the peoples.

In February ‘95, former president Zedillo announced the issuance of arrest warrants and military incursions that resulted in a deepening of the occupation of the armed forces in the state of Chiapas -which have remained until now-. It’s the military logic of a path of war against the peoples in resistance; it’s the continuum of the Mexican government that opted for extermination.

The incursion of the Mexican Army into the Chiapas Jungle had the purpose of arresting the EZLN’s leadership, which caused the forced displacement of thousands of people that fled into the mountains; others suffered arbitrary imprisonment, extrajudicial executions, forced disappearances, torture, illegal searches, violations of the right of the freedom to travel because of the installation of military checkpoints that caused terror in the region, permanent military and paramilitary harassment, among other grave human rights violations. Acts denounced by the EZLN on February 11, 1995:

“The Federal Government is acting with lies, is making a dirty war on our towns. Yesterday at noon, 4 helicopters bombed the area on the outskirts of Morelia and La Garrucha, as well as machine-gunning the area under Zapatista control, thousands of federal soldiers penetrated the jungle’s interior, through Monte Libano, Agua Azul, Santa Lucia, La Garrucha, San Agustín, Guadalupe Tepeyac and others. They are extending a ring of death. We Zapatistas, troops and civilians, up to now have done everything possible to retreat, but we no longer have any other option than to defend ourselves and our peoples, thousands of civilians who have been displaced from their homes. Brothers, the government of Ernesto Zedillo is killing us, is killing children, is beating women and raping them.”1

This genocidal policy of the Mexican State is remembered for the proliferation of paramilitary groups in the territory, sustaining the impunity that is currently reactivated with the successor groups of para-militarism in the Highlands. In Aldama and Chalchihuitán municipalities there is a critical situation of human rights violations, causing thousands of people into forced displacement and generalized violence that doesn’t stop. The sign of this time, like on ’95, is of terror anchored in the perverse indifference of the Mexican government.2

The violence intensifies with the reactivation of armed groups that operate in the Jungle Zone and seek to dispossess the EZLN’s territories where the Zapatista towns and communities are settled in the Moisés Gandhi region, official municipality of Ocosingo, acts perpetrated by the Regional Organization of Ocosingo Coffee Growers (ORCAO, its initials in Spanish). That’s in addition to the attacks on territories located in the Zapatista community of Nuevo San Gregorio, in the official municipality of Huixtán. Attacks that are articulated in the follow-up to a strategy that comes from the factual powers and the municipal, state and federal governments that promote the counterinsurgency that doesn’t stop, in this persistent action of beating the processes of autonomy that are maintained against the grain of the capitalist system.3

Betrayal as an extermination strategy comes from the power of the State that proposes colonization based on territorial dispossession of the peoples, as an example in Mexico: the Morelos Integral Plan, the Interoceanic Corridor, the “Maya” Train and its development poles that threaten live. Nevertheless, the struggles for the horizons of life are being promoted from the peoples and the communities, in the movements in defense of humanity and Mother Earth, as has been expressed in the signatures that were added on the document convened by the EZLN: “A declaration… for Life”,4 wherein there is a hope of world action that promotes the continuity of a change in the system that has repercussions on a society necessary for the time of the peoples.

Jobel, Chiapas México,

February 10, 2021

* Pedro Faro Navarro is currently the Director of the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas.

1. February 11, 1995: https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/1995/02/11/llamado-a-detener-la-guerra-genocida/

2. Faro, Pedro: https://frayba.org.mx/desplazamiento-forzado-en-chiapas-los-impactos-de-la-violencia-y-la-impunidad/

3. Report from the Caravan of Solidarity and Documentation with the autonomous Zapatista communities of Nuevo San Gregorio and Moisés Gandhi Region. November 11, 2020.

4. A declaration for life: https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2021/01/01/part-one-a-declaration-for-life/

Originally Published in Spanish by Desinformemonos, Thursday, February 11, 2021,

https://desinformemonos.org/traicion-de-febrero-la-huella-de-la-guerra-que-continua/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

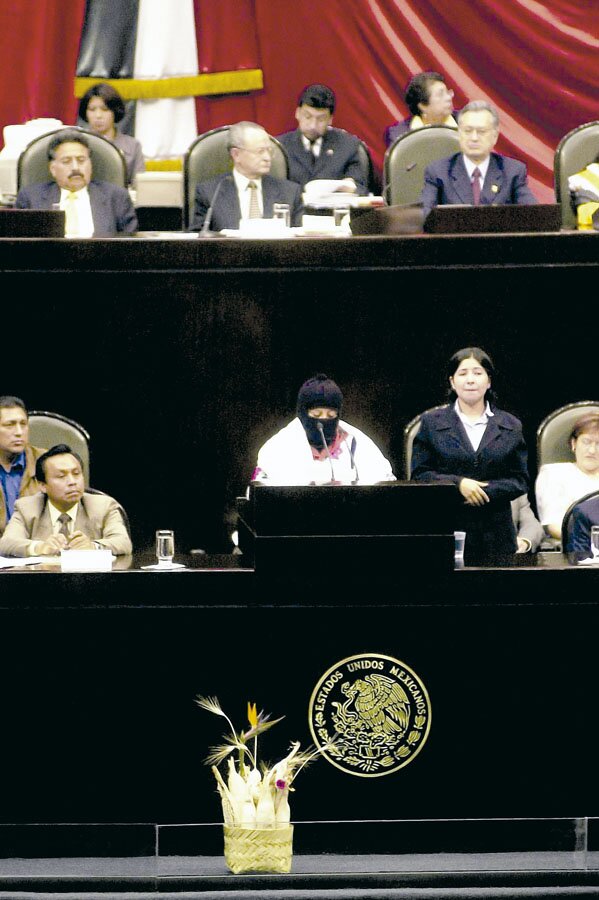

The San Andrés Accords, autonomy vs. neo-indigenism

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

This February 16th marks the 25th anniversary of the signing of the San Andrés accords on indigenous rights and culture. Much has changed since then, but one thing remains: indigenism as a State policy.

Indigenism is the name given to institutional policy aimed at serving the indigenous population. Simultaneously, it is an anthropological theory, an ideology of the State, and a governmental practice. Its central objective is to protect the indigenous communities, integrating them with the rest of national society, diluting their character as a people and as a historical subject. It is policy of the non-indigenous towards the indigenous, although its architects might belong to some ethnic group.

One of its primary promoters, Alfonso Caso predicted that within 50 years, there would be no more indians: all would be Mexicans. He wasn’t alone in this enterprise. Many thinkers, before and after him, have seen the inexorable destiny of the indigenous peoples, in the integration of the mestizo national society.

Despite the fact that the Mexican nation has had a pluri-ethnic and multicultural make-up since its founding, its constitutions have not reflected this reality. Erasing the Indian from the country’s geography, making them Mexican, forcing them to abandon their identity and culture, and folklorizing them, has been an obsession of the ruling classes since the Constitution of 1824. The intention of building a Nation-state, of casting off the colonial heritage, of resisting the dangers of foreign intervention, of combatting ecclesiastical and military jurisdiction, and of modernizing came to prioritize a vision of national unity that excluded the pluri-national reality.

The Accords of San Andés were intended to celebrate the funeral of indigenism and resolve this historical debt. Its central point consisted in the recognition of the Indian peoples as social and historical subjects and the right to exercise their autonomy.

Autonomy is one of the ways of exercising self determination. Its practice implies the real transfer to the indigenous peoples of the abilities, functions and competencies that today are the responsibility of government entities.

The Zapatistas invited writer Fernando Benítez, who had dedicated 20 years of his life to defending and studying the native peoples and was the author of five monumental books on them, to the San Andrés dialogues as an advisor. The journalist gladly accepted the proposal.

His motivations were genuine. What did the Indians teach me?, Benítez asked himself at the end of his life. They taught me to not believe I was special, to behave impeccably, to consider the animals, plants, oceans and skies, to know what democracy and respect for human dignity consist of. And also to go from the everyday to the sacred. ( La Jornada, 5/7/95).

Although many of the problems that they faced were the same, the perspective of struggle of the Indians that participated in the dialogues was completely different than those described by Benítez since 1960. The author of The Indians of México perceived the people as being most miserable, the poorest campesinos, those that live on the worst lands in a country of bad land, the ones being invaded. He anticipated the inevitable doom of disappearance of their cultures and their replacement by the debris of industrialism. And he proposed to rescue what was left of the indigenous cultures, before the end of the process. (https://bit.ly/3p50tRf).

But they didn’t disappear. On the contrary. They became more present than ever. Certainly the indigenous convened by the EZLN, first to the dialogues and later to the formation of the National Indigenous Congress, suffered the effects of internal colonialism, and therefore came from regions beset by dispossession, oppression, exploitation and discrimination, similar to those described by Benítez. However, far from representing cultures on the border of disappearance, these leaders were a living expression of a formidable capacity for resistance and of reinvention of the traditions of their peoples.

San Andrés was attended by indigenous leaders that emerged during the 1970’s and stepped into public light as a result of the Zapatista insurrection, together with traditional community authorities. Also participating were prominent indigenous intellectuals, who had elaborated a rich reflection about how to reconstitute their people.

Twenty-five years after the signing of the agreements and the founding of the CNI, some of the indigenous people who participated passed away. Others have incorporated themselves into the ranks of the government in office, from the PAN to the 4T. However, the movement born of this process, oriented toward the construction of autonomy and the struggle against capitalism, is more vigorous and solid than two and a half decades ago. Hundreds of new leaders and dozens of intellectuals (including many women) have taken the generational baton.

Two and a half decades after the accords of San Andrés were signed, the Mexican state continues its failure to comply. Additionally, the autonomous indigenous movement suffers the murder of its leaders and the federal government’s promotion of a neo-indigenist welfare program that goes hand in hand with the promotion of megaprojects on their territories. (https://bit.ly/3oXetMs).

————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Tuesday, February 9, 2021

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2021/02/09/opinion/017a1pol

English Translation by Schools for Chiapas

Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

The war of attrition against the Zapatista communities

“No more paramilitaries in Zapatista communities.” Photo: Elizabeth Ruiz

The strategy of the Andrés Manuel López Obrador Government is completed with the installation of new camps and National Guard bases in the Ocosingo region, which goes hand in hand with the reactivation of armed groups such as the ORCAO that act as paramilitaries.

By: Raúl Zibechi

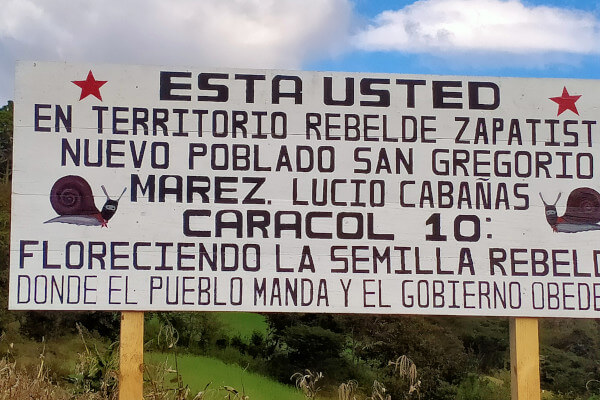

“We are not owners of the land, we are its guardians. The land is for living, not for doing business,” says a young man from Nuevo San Gregorio community, Lucio Cabañas Autonomous Municipality, Caracol 10, in the official municipality of Ocosingo, Chiapas.

“We are enclosed in our own land,” adds a woman from the same community who is being besieged by 40 armed invaders with support from the Government. She explains that despite the fence siege, the families have mounted a carpentry workshop, and they make embroidery and mecapal [1] as a form of resistance.

Those are testimonies collected by the “Solidarity Caravan,” made up of more than 15 collectives adhered to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, while in Nuevo San Gregorio community as well in the five communities that make up the Moisés Gandhi region, which is in the Lucio Cabañas Autonomous Municipality, in the official municipality of Ocosingo.

Members of the Ajmaq Network of Resistance and Rebellion explain to us from San Cristóbal de Las Casas that it’s about more than 600 hectares that were recuperated by the Zapatista bases during the 1994 offensive and that are now being surrounded by “medium-sized property owners and people allied with the federal government, as well as the state of Chiapas government” and by members of the Regional Organization of Ocosingo Coffee Growers (ORCAO).

In Moisés Gandhi, inhabited by hundreds of families, the attacks began on April 23, 2019, with shots from high-caliber weapons from 5 am to 9 pm, a situation that the Government doesn’t want nor has the will to stop. Ever since the attacks began, in April 2019, groups of 250 to 300 armed people arrived in vehicles on various occasions, burning houses, stealing and destroying crops. On several occasions they have kidnapped comuneros (community members), beaten them, threatened them and then released them.

On August 22, 2020, they burned a Zapatista coffee warehouse at the Cuxuljá Crossroads, a strategic highway crossing that connects to San Cristóbal and Palenque.

Were dealing with new forms of counterinsurgency that are adapting to the growth and territorial expansion of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN), which now has 43 centers of resistance. Members of the caravan explain that the ORCAO’s members are politicized people who know the Zapatista movement well.

For years they have been attracted to the social programs that offer them economic resources if they regularize the land; they can then capitalize and go from being poor campesinos to rich campesinos, acquiring power. The ORCAO sells its coffee to large companies linked to Wall Mart, since it has aspirations to make big profits.

“The form of operating consists of enclosing the homes, clinics and schools of Zapatista families and communities, thereby preventing them from continuing to produce, configuring a comprehensive war of attrition [2] that seeks to break the autonomous economy,” members of the Ajmaq and the solidarity caravans explain.

It’s impossible not to connect this situation with what were the social policies of the progressive governments in South America. They not only transferred resources to poor neighborhoods and communities, they also sought that the intermediaries were popular organizations and movements that previously had struggled against the neoliberal governments. In that way, they incorporated people who had in-depth knowledge of the movements, knowledge that the States were unaware of, into official policies.

“We don’t give up here, we continue organizing our collective work,” the communities assure. In order to maintain the resistance, they organize collective work, to ensure food and health. The decision to resist peacefully, without violence but without abandoning the struggle, has enormous costs that the Zapatista bases are willing to face.

“It’s not a coincidence that the ORCAO is attacking the new Zapatista Good Government Juntas and centers of resistance, because the majority there are young people and women and they seek to discourage and frighten them,” say members of the caravans.

For this reason, in addition to fencing community lands with wire, they break water pipes, surround natural springs, pastures where cattle feed and prevent them from harvesting. In Nuevo San Gregorio, the Zapatista support bases recognize that this year they could barely harvest 50% of what they harvested last year. The objective is to create a humanitarian crisis that forces the Zapatista families to abandon the lands that they recuperated by struggling.

The strategy of the Andrés Manuel López Obrador Government is completed with the installation of new National Guard camps and bases on the Ocosingo region, which goes hand in hand with the reactivation of armed groups like the ORCAO that act like paramilitaries.

“We don’t surrender, we continue organizing our collective work here,” the communities say. In order to maintain the resistance they organize collective work to ensure food and health. The decision to resist peacefully, without violence but without abandoning the struggle, has enormous costs that the Zapatista bases are willing to face.

From above they seek confrontation between peoples, supporting social organizations that have the complicity of the municipal, state and federal governments, for the purpose of undermining the Zapatista autonomy that is one of the principal hopes that illuminates the planet.

[1] Mecapal is a strap attached at both ends to a sack and placed on the head to carry a load. The English word is tumpline. For those familiar with Chiapas and/or Guatemala, it’s used for carrying firewood.

[2] War of attrition – this is also known as a “low-intensity” war, or a war of exhaustion (from wear and tear).

——————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by El Salto

Friday, February 5, 2021

https://www.elsaltodiario.com/mexico/guerra-de-desgaste-contra-las-comunidades-zapatistas

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Background: The three gazes of the original peoples

In the Year 2-Covid 19, or Year Twenty-One-Reed [Aztec calendar] of the current century, many people in many places have lost their bearing. The semi-paralysis induced by the pandemic provided the State with a distinctly new twist in the unstoppable militarization of the country. With all the best excuses, as always. Ever since the Army emerged from their barracks in 1994 and, especially in 1995, its presence has only increased in the rural and indigenous plazas, cities, roads and regions throughout Mexico. One even wonders if there are any troops still left in the barracks.

Since then, all kinds of special, semi-militarized police forces have been invented, first in order to fight the indigenous subversives in Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero; and later to make war on organized crime. And frequently on the population as well. The security theme became the favorite excuse of the powers that now seek to centralize even our identities through a universal ID card, Chinese- style. This is not a new project. Previous governments have attempted the same. Maybe in those days we were still concerned about the spying, the phone taps, the tails on people suspected of something. Today nobody cares if they are being spied on or can’t evade it (because they can’t). So the State will have a file on each of us, making us all equal on this front, in cybernetic fulfillment of the old liberal dream of mestizo Mexico: to make Mexicans uniform under the liberal guise of “equality” that has been filled with nuances and misgivings in the postmodern sensibility. For the original peoples, in particular, this means de-indianizing them rather than recognizing their local sovereignty, their right to different forms of government, agricultural production and communal forms of life that have survived, being indomitable, for centuries, despite many governments’ failed attempts at extermination, often “benevolent” but relentless.

Those who think it’s different now are wrong. Rhetoric has abounded: from the independencistas, the Juaristas, the Porfiristas, the Maderistas, the post-revolutionaries, the nationalists, the neoliberals (from Salinistas to Calderonistas). From the perspective of the peoples, the changes in discourse do not change things: for a century they have been eating promises, from political party to political party, from church to church. Meantime their territories diminish, surrounded by urbanization, highways, trains, mines, wells, agroindustries, tourism. Property rights are continually denied to them, and those they have won, disappear. The concept of “indigenous autonomy” does not exist in the lexicon of any president.

As always, the State and a good part of the majority society that lives on the train of consumption and individualism, applaud diversity, pluriculturalism, roots and identity, but actually they present an obstacle for them. It’s been 27 years since the indigenous uprising of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN); and since then there has been no stopping the indigenous challenges to State control. In 2021, amid the adversity of the pandemic, the very EZLN that built real autonomy –without permission, but with efficiency and legitimacy– makes an international statement that somehow breaks out of encirclement of the nationalist autism that the government is trapped in. Like other times, it seems like an adventure, an unexpected proposal that goes against the current, a game change. Whether or not it succeeds, above all it reminds us, in Mexico and in many other parts of the world, of the reality of the originary peoples, and their importance in a future that is not shit, and their courageous defense of the territory, the water and self-governed communality.

The words of Old Antonio, cited in “The Mission” a recent communique by subcommander Galeano of the EZLN (December 2020), which is itself a followup on the “Declaration for Life” made available in January, sets things straight again from and for the original peoples’ gaze:

“Storms respect no one; they hit both sea and land, sky and land alike. Even the innards of the earth twist and turn with the actions of humans, plants, and animals. Neither color, size, nor ways matter,

“Women and men seek to take shelter from wind, rain, and broken land, waiting for it to pass in order to see what is left. But the earth does more than that because it prepares for what comes after, what comes next. In that process it begins to change; mother earth does not wait for the storm to pass in order to decide what to do, but rather begins to build long before. That is why the wisest ones say that the morning doesn’t just happen, doesn’t appear just like that, but that it lies in wait among the shadows and, for those who know where to look, in the cracks of the night. That is why when the men and women of maize plant their crops, they dream of tortilla, atole, pozol, tamale, and marquesote [vi]. Even though those things are not yet manifest, they know they will come and this is what guides their work. They see their field and its fruit before the seed has even touched the soil.

“When the men and women of maize look at this world and its pain, they also see the world that must be created and they make a path to get there. They have three gazes: one for what came before; one for the present; and one for what is to come. That is how they know that what they are planting is a treasure: the gaze itself.”

It’s not just the pandemic. Huge floods, large-scale droughts, poisoned rivers and soils, cleared forests, destroyed coastlines, construction projects that invade natural areas, including virgin territories, are all part of the storm. Ancient villages and their regions are endangered, the jaguars and the mangroves are endangered. The conflicts of land dispossession are now compounded by torrential conflicts over water. The bids are coming in on the stock exchange, dispossession multiplies. Soon it will be the cause for wars.

For the men and women of maize, their gaze is the treasure that allows them to remain steadfastly in the world, not to confuse the compass nor to lose their way. In fertile summers and in hard times, the originary peoples’ view what is coming with a farmer’s persistence and a millenarian efficiency. They are the only ones who think the earth is not for them, but for their children and beyond. The struggle is in the long term.

[Originally published in Spanish and excerpted from the “Umbral” column of Ojarasca : Las tres miradas de los pueblos originarios] Translation provided by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Indigenous people file suit against National Guard over construction of barracks in Chilón

By: Editor, Yessica Morales

Photo: Maya Tseltal people in Chilón municipality have undertaken a legal battle against the militarization of their territory.

The Tseltal people asked for protection from federal justice against the construction of the National Guard barracks and also that the Attorney General of the State of Chiapas desist from taking criminal action against José Luis Gutiérrez Hernández and César Hernández Feliciano, repressed and criminalized for demonstrating against said project.

Juana Hernández, Gilberto Moreno, Juan Jiménez and Jerónimo Jiménez, representatives of the Tseltal Maya people in Chilón municipality, together with the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) and the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center (Centro Prodh) announced the admission of a demand for an amparo (suspension) filed over the construction of a National Guard General Barracks in their territory, without having been consulted in a prior, free and adequate way to grant or not their consent.

Jerónimo Jiménez emphasized that it’s not the first time Chilón experiences the impacts of the militarization of their territories. During the epoch of the armed conflict in the state of Chiapas, in 1995, an army barracks was installed in their territory, which was not withdrawn until 2007, after years of an organized resistance on the part of the community.

There had been a military camp in the San Sebastián Bachajón Ejido since 1995. Upon its surprise arrival with violence, they took possession of the ejido house and didn’t allow the ejido owners to hold their ejido assemblies. There was a house on land near the ejido house that belonged to Pedro Perez (…), the owner. When they no longer permitted him to enter (…), they spoke to the Army and the response was that his house was now in the federal area and, therefore, it no longer belonged to him, Jiménez explained.

They emphasized that thirteen years later, in October 2020, residents of Chilón municipality entered into the agreement between municipal, state and federal authorities, including the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA), to cede land within their territory for the construction of the barracks that will shelter the National Guard. Consequently, on October 15, 2020, they exercised their right to demonstrate. In response, there was a deployment of more than 300 members of different security corporations for the purpose of stopping the mobilization. They used excessive force against the demonstrators.

We demand the freedom of the two political prisoners César Hernández Feliciano and José Luis Gutiérrez Hernández.

They added that private vehicles were damaged and several people were injured in the eviction, in addition to the solitary confinement and subsequent deprivation of freedom of community social defenders José Luis Gutiérrez Hernández and César Hernández Feliciano, who still face unjust criminal proceedings in from the Indigenous Justice Prosecutor’s Office for the crime of rioting.

Knowing the impacts that military projects can have on their community life, they organized to initiate a legal process by means of a commission named in their traditional assembly. Said strategy consisted of filing a lawsuit demanding a suspension (amparo), which was admitted by the Fourth District Court in matters of Amparo and Federal Trial based in Tuxtla Gutiérrez last December 9, 2020, file number 717/2020.

The lawsuit denounces that the license and construction of the Barracks is about se about an imposition of a militarization project that violates the rights of the people of Chilón municipality to prior, adequate, free and informed consultation, to self-determination, to territory, access to information, among other rights protected by the Mexican Constitution, as well as international treaties, including the American Convention on Human Rights and Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO).

The foregoing is due to the fact that it’s clear to the inhabitants that the National Guard is a de facto military security force, rather than a civilian body. Therefore, the project should not have been conceived without consultation because it will have direct effects on their right to self-determination, the protection of territory that constitutes a fundamental part of their community harmony and respect for their identity.

They added that, with the presence of militarized security forces in the zone, they fear that sex work will be promoted, that alcoholism will be accentuated as a control measure and that community division will occur, as happened in the past.

They explained different and forceful arguments to avoid causing irreparable damage to the territory of the Tseltal Maya peoples for which the Fourth District Court should have ordered the suspension ex officio and flatly, however, the Judge denied it.

This Friday, January 29, the Fourth District Court has a new opportunity to declare the origin of the definitive suspension, allowing the Tseltal Maya peoples to have the assurance that their territory and their collective rights will not be permanently affected until the aforementioned amparo lawsuit is resolved, they ended.

——————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo

Wednesday, January 27, 2021

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Tour for life and hope

For Life

By: Raúl Zibechi

In all corners of the world those above are perpetrating a silent genocide of Native and Black peoples, of campesino and poor people, of the city and the countryside.

The Turkish Army invades northern Syria, devastating Kurdish villages and cities. The government of Israel doesn’t vaccinate the Palestinian population. In Manaus (Brazilian Amazon), thousands die in collapsed hospitals. In just three weeks of 2021, there have also been six massacres in Colombia, resulting in more than 15 deaths (https://bbc.in/36fznA2).

Femicides multiplied during the pandemic, as an inseparable part of the genocide against those below.

In Chiapas, the paramilitary gangs attack the communities in Moisés Gandhi with firearms. The script is always the same: paramilitaries like ORCAO, with advice from the armed forces, attack Zapatista support bases; the federal and state governments are silent; that is, they consent. The media and the parties are silent; that is, they consent.

In the Latin American urban peripheries and in remote rural areas not only are vaccines not talked about, but we also don’t have adequate hospital infrastructure, nor enough doctors or nurses.

One characteristic of the storm against those below is that no one cares. No one reacts or is moved. Indifference is the policy of the states and of a good part of public opinion. Ayotzinapa happens everywhere, not only in Mexico.

This is the policy consolidated from above, and accepted with enthusiasm by the political system. It is a military and media siege against the peoples, to immobilize them, while capital (freed from all controls) deepens its extensive and intense process of concentration and centralization in fewer and fewer hands.

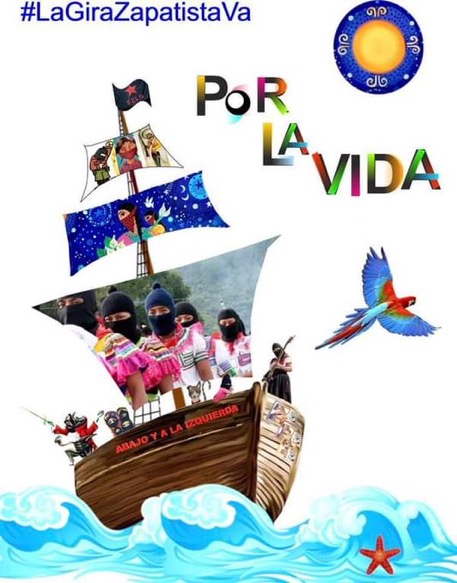

The Zapatista tour of European lands is an opportunity to break the siege, to once again gather in common spaces, to make ourselves heard and to weave ourselves together as peoples in resistance. The Zapatista proposal announced in October and restated on the 1st of January in the Declaration for Life is an enormous effort on the part of the communities to break the siege of death.

The response from Europe came from the hand of more than a thousand collectives in more than 20 countries declaring their willingness to join and organize the tour that will carry more than 100 Zapatistas, mostly women, to many corners of the continent.

It will not be easy to organize a tour so extensive in a moment in which the pandemic knows no bounds, offering an occasion for the governments and the police to limit collective action. In Europe rights to gather and demonstrate were limited, which is now casting doubt on how the celebration of March 8th will go.

Also it will be very challenging for thousands of activists to manage to come to agreement, being that they come from different histories, ideologies and ways of being. These diverse political cultures will find difficulties in overcoming both individual and collective egocentrism, the inevitable search for media spotlights for some, always few, but with great power for disintegration.

To the difficulties inherent to the situation, you have to add those stemming from so many years of fragmentation, and above all, the continuity of a political culture centered on the states, on male leaders, and on discourses that are not accompanied by coherent practices.

The Zapatista expedition offers the opportunity to address two necessary tasks, besides that of the aforementioned breaking of the siege.

The first is that it will allow the linking and coordination of collective that are usually distant or that don’t even know one another. This isn’t about creating new apparatuses or structures, but rather of opening a wide spectrum of horizontal and egalitarian links, something much more difficult even than establishing a coordination that often repeats the defects of the apparatus.

The second is that a deeper understanding of Zapatista ways of doing things can allow many people and collectives to enter into political cultures that until now only a few feminist and youth groups have put into practice.

One of the most depressing observations in militant environments is seeing how decade after decade they tend to repeat the same defects that, naively, we believe we have overcome. There is no way of overcoming those without doing, failing, and doing again, until you find ways of working that don’t hurt, or exclude, or humiliate.

The Zapatista tour will be an enormous source of learning for the most diverse anticapitalist collectives. First, to confirm that it is possible, that those from above are not as powerful as they seem. Second, that we can add more and more people without reproducing the system, looking for confluences among those who suffer similar oppressions. Challenge and hope at the same time.

If all goes well, in the south of the continent we will reproduce the expedition. These days we are taking the first steps, timid for now, to deploy the energies that will allow us to continue breaking sieges.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Friday, January 29, 2021

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2021/01/29/opinion/013a2pol

English interpretation by Schools for Chiapas

Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

The Maya Train and the Mexican State versus the UN

By: Magdalena Gómez

Six rapporteurs of special human rights procedures sent the Mexican State, through the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, a document in which they expressed “grave concerns” about the Maya Train on issues of territory, dispossession and rights to health, the negative effect on the right of the indigenous peoples to their traditional lands, consultation without international standards, irregular environmental impact studies and possible harassment, criminalization, defamation against human rights defenders personas, as well as possible militarization of the zone (September 21 Communication to Mex 11/2020).

On November 20, 2020, the permanent mission for Mexico in the United Nations office and other international organisms with headquarters in Geneva sent the response of Mexico (OGEO4560). In it, it repeats positions like the defense of the consultation process and its consistent innovation in which specific consultations will follow, as well as the follow-up commissions agreed upon when the train was approved. At the same time it reaffirms controversial issues, like the trusts and, based on the powers of the State in matters of expropriation for reasons of public utility, now it recognizes that in the case of evictions it will seek negotiation, but if that doesn’t work out indemnification is imposed. They left out of their response the ongoing legal avenues promoted by indigenous organizations in the national ambit, as well as their initial search at the inter-American level, which doesn’t operate with the required speed. Its big omissions are those relative to the indigenous peoples, the Maya civilization and the so-called archaeological remains, the impacts they have suffered with other megaprojects and to their very concept of so-called progress.

To start with, the Mexican State offered a definition: “The Maya Train is a project for improving people’s quality of life, caring for the environment and detonating sustainable development;” then, it enunciates its objectives, without highlighting tourism. It also introduces, without defining, that what were once development poles will now be “sustainable communities” and clarifies that they do not report their location in order to avoid speculation.

In the land section, they pointed out that the current legislation establishes that the general communications routes are national assets and the railways, stations, train yards, traffic control centers and right of way, are part of the general railway communication. The national assets will not be part of a trust since they belong to the nation, if not enough, the constitution of the trusts to which the lands will be contributed according to their regime (federal, state, municipal, private or ejido) has been considered. If in any of these cases it is determined that it’s necessary to incorporate common use lands belonging to an ejido, their participation will be carried out in accordance with Agrarian Law, which permits the association in participation for 30 years with the possibility of renewal.

This way will permit that we’re not dealing with what are called infrastructure and real estate trusts (Fibra) in all cases. And they maintain that under no modality is it foreseen that common use ejido lands will be converted into private property.

Regarding the concern of the rapporteurs about the military participation in indigenous territories for the construction of sections 6 and 7 of the Maya Train Project, they responded that it’s based on the Organic Law of the Mexican Army and Air Force. For greater support, on January 11 the addition of a section to Article 29 of the Organic Law of Federal Public Administration was published in the Official Gazette of the Federation, relative to the functions of the Secretary of National Defense: “Providing auxiliary services that require the Army and Air Force, as well as the civil services that the federal Executive designates for said forces.”

The response has a political-diplomatic impact, the efforts of the rapporteurs would only reach to carry out a follow-up to its content; these procedures do not have a binding character. Accompaniment of the government was agreed upon with the Mexico office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights that hopefully maintains priority, as it has up to now, on the rights of the peoples.

It’s a fact that the so-called Maya Train will continue for the rest of this six-year presidential term. The challenge that remains for the communities is to continue the task of information about the impact of the megaproject and carry out the follow-up and denunciation of land dispossession situations in the ejidos. We’re facing a case of submission of the law due to the disproportionate use of State’s political force.

—————————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Tuesday, January 19, 2021

https://www.jornada.com.mx/2021/01/19/opinion/013a2pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Background: Zapatistas, a 25-year transformation

By Herman Bellinghausen

The theory of the gourd

They made us believe that Mexico was a sort of large, mature, shiny and solid gourd for export. The government headed by Carlos Salinas de Gortari, obsequious and gallant, extended the gourd on a silver platter to the gold partner, and from there to the global free market in the northern hemisphere. How smooth and shiny the gourd, also called a snout, looked. And then, at the appointed date and time, the champagne’s plop became a gulp of thunderous disbelief in the throats of the celebrating rulers. On New Years Eve 1994 the precious gourd cracked. An inopportune crack that burst into a complaint of unprecedented eloquence, a “today we say enough” shouted with rifles in the fist and badly covered faces from the last corner of the country, in the mountains of Chiapas. Through the crack, the words of the First Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle and the incomprehensible images of a campesino and insurgent army that occupied the seats of government in some cities of the sprouted uncontrollably. It was a declaration of war with all its letters. And that army “that couldn’t be” announced that it would advance to the capital of the Republic to overthrow the bad government, based on Article 39 of the Constitution and taking refuge in the Laws on la War dictated in the Geneva Convention. It seemed like a joke, a bad dream. Many would have wanted to laugh, but couldn’t. Through the cracking of the gourd, the indigenous peoples finally appeared, claiming their place in the nation and in History. Even now, it seems incredible what they achieved in one night, when they declared:

“We are the heirs of the true builders of our nation, the dispossessed. We are millions and we call upon our brothers and sisters to join this call as the only path to not die of hunger given the insatiable ambition of a 70-year old dictatorship led by a click of traitors who represent the most conservative and sell-out groups. They are the same ones who opposed Hidalgo and Morelos, the ones who betrayed Vicente Guerrero, the same ones who sold more than half our soil to the foreign invader, the same ones who brought in a European prince to govern us, the same ones who formed the dictatorship of the Porfirista scientists, the same ones who opposed the oil expropriation, the same ones who massacred the railroad workers in 1958 and the students in 1968 and they are the same ones who today take everything away from us, absolutely everything.”

And to the people of Mexico they said:

“We, honest and free men and women, are conscious that the war we declare is a last resort, but just. The dictators are applying an undeclared genocidal war against our peoples for many years. Therefore, we ask for your decided participation supporting this plan of the Mexican people who struggle for work, land, housing, food, health care, education, independence, liberty, democracy, justice and peace. We declare that we will not stop fighting until achieving these basic demands of our people by forming a free and democratic government in our country.”

No one had dared to speak to the State like that in decades, and in the case of indigenous peoples, in centuries. The name of the insurgent group: Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, its initials in Spanish), would remain forever tattooed on the skin of the Mexican State. Indigenous peoples, they immediately specified being Tsotsil, Tzeltal, Tojolabal and Chol Mayas, and also Zoques. From there they could be any of the native peoples of Mexico. They woke up with a bell ringing, and with it they awakened the entire country, and also the world.

You know what? Mexico turns out to be the country with the largest Native population on the continent: at least 25 percent of the total in the Americas. They number many millions, perhaps twenty million or more, although officially the censuses lower the numbers in a sort of statistical genocide, forever a characteristic of the method. And even so they are still the fourth part.

President Salinas, still pale days after the New Year in that long January of ‘94 and visibly diminished, would declare that the indigenous people who were disaffected with the regime were only a few, that they came from a few Highlands municipalities and that the situation was already being addressed. Aha, deploying thousands of military personnel in the region, kilometers-long convoys loaded with troops, airplanes, tanks and helicopters that shot at and bombarded a target that had vanished. Just as they appeared out of the night, they returned to it. The jungle swallowed them up. Now, the government was at war with indigenous Mexicans, whose reasons sounded convincing, at least so that everyone would turn to look. Through the crack in the gourd a bath of reality would continue to emerge like a light (Carlos Monsiváis would admit that “the Zapatistas taught us to speak with reality”) that no one could contain; to the contrary, it grew. The cracked gourd shed a new light, very new, on the national debate and on a brand new central actor: the Native peoples. Moreover, it seemed like the resurrection of the libertarian dream that had buried the Berlin Wall a few years ago when the cracks finally brought it down. If Leonard Cohen sang that that the cracks are where the light enters, the indigenous glow came from the interior of Mexico itself, “deep Mexico,” and no one could say that he had not seen it.

As much as there is to go in 2019, for the full vindication of the Native peoples, the arch opened by the neo-Zapatistas of Chiapas has knocked down like cards a number of prejudices, denials, discriminations and impunities. Today, explicit racism, discrimination against indigenous women and discrimination against Native languages are visible and “politically incorrect.” It doesn’t mean that they no longer exist, but the margins for the hypocrisy of the majority society were narrowed. The gourd was definitely broken.

Never more a Mexico without her peoples

The wake of the uprising, its impact on the country’s Native peoples, is a matter little addressed by analysts. It will be remembered that the surprise of that New Year had already been announced. In the middle of 1993, national media and international agencies reported the federal Army’s clash with some kind of guerrilla in the Ocosingo canyons (Cañadas), near Chalam del Carmen, at the gates of the Lacandón Jungle of the Tzeltals. The government immediately minimized it; the Army denied the existence of guerrillas, and did so without counting that the new Secretary of the Interior had governed the state [of Chiapas] autocratically until a few months before. The State supposed that the situation was under control. There would be elections the following year and the Cardenistadanger seemed averted when the left joined the electoral system and remained at its “real size.” No one foresaw that the winds of change would come from far below. When did the Indians here represent a real challenge for the State? They were clients, nothing more.

But the unforeseen winds did come blowing down there. In the Autumn of 1993, chance, if it exists, took me from San Cristóbal de Las Casas to the Tojolabal cañada (canyon) of Las Margaritas, to a community, then semi-remote, called Cruz del Rosario, to visit some coffee fields. Not me, my companions. I was “wearing a cap.” And we’re going there in a pickup truck with cañada bars inside. In Cruz del Rosario, our host, a Tojolabal resident, told us about his quetzal hunts in the mountains, how much he sold them for, especially alive. With the same lack of modesty he narrated the movement of “guerrillas,” who came from the direction of Tepeyac (Guadalupe Tepeyac, which would become famous in a few months) and who were known to have two commanders: one tall, a little redheaded; another short, “indigenous but not from around here.” With time, it would be easy to deduce that he was talking about Subcomandante Pedro and Major Moisés of the EZLN. I don’t remember that he approved or disapproved.

A peculiar nervousness prevailed everywhere. In San Cristóbal and Ocosingo the caxlan (non-indigenous) merchants suffered apocalyptic visions. Days later in Jovel, during the 20th anniversary of the Rural Association of Collective Interest (ARIC, its initials in Spanish) snubbed by the Salinas government to which its leadership had surrendered, the powerful organization of indigenous producers, still undivided but already diminished, was getting chills. “They are taking our young men from us” caxlan leaders and advisors lamented with galloping paternalism and baseless political calculations.

Signs of “something” serious abounded. More and more radically indigenous in its orientation, the diocese headed by Samuel Ruiz García lived under siege, the “authentic” coletos [1] and cattle ranchers of the region brought their desires to the bishop, to his parish priests and catechists, to the liberated communities, to the new Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, which today we nickname Frayba. The internal commotion was evident in the historic organizations and unions (National Campesino Confederation [CNC], Independent Central of Agricultural Workers and Campesinos [CIOAC] and the ARIC). The “traditional” Catholics of San Juan Chamula had barely laid down their criminal weapons against the “Protestant sects,” with which they provoked the exodus of more than 30 thousand Chamulans to San Cristóbal and the border. Meanwhile, the web of secrecy grew in the barrios, cañadas, schools and convents.

After the almost autocratic rule of Governor Patrocinio González Garrido until a few months ago, when his political cousin, President Salinas, shortened his reins by bringing him to the Interior Department, Chiapas seemed to be without a government or having it somewhere else (a recurring syndrome in the state).

Nothing permitted foreseeing the size of the impact that three months later the irruption what turned out to be the Zapatista National Liberation Army (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) would have. Immediate, profound, worldwide, it surprised the insurgents, the Catholic Church and the government. The media was ecstatic. The weeks after January 1, 1994 revealed a vast movement, organized and disciplined, full of meaning, of ideas and experiments, of unprecedented political gravity and humor. Its base, its all resided in the telluric force of thousands of masked and armed indigenous people in rebellion.

Many were the unforeseen effects of the rebellion that mobilized multitudes in the entire country, generated solidarity networks of a new kind and inspired rivers of ink, photography, video (on the then incipient Internet, the EZLN’s communiqués were translated the same day into English, Italian, German, French and other languages), whose messages led to the creation of musical genres and propaganda arts that Europe and the Americas turned to see with astonishment.

Less evident, ignored by everyone, the greatest impact occurred in the Native peoples themselves. Communities and individuals throughout Mexico learned that it was possible without fear. They embraced their languages. Women learned to be alluded to as never before. Young people glimpsed another possible modernity: a world where many worlds fit, where they fit. The mountains and the Lacandón Jungle were open to an evolving experience of government and struggle. The rebels legitimized themselves in their actions and their language. With the word on their side, the indigenous people took the lead for the first time in the history of Mexico.

A very different country

There are triumphs that seem like defeats: the student movement of 1968, the 1988 fraud and the strike of the General Strike Council in 1999. As distant as ‘94 may seem in 2019, that Mexico of capitalist pillage, liberal glee and reality baths is still here, sudden and brutal. That event gave rise to new social dreams. Also to an internal “low-intensity” war,” which, mutatis mutandis, continues today in those same mountains of Chiapas and in many mountains and plains of the republic. The government of Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León inaugurated the modern era of massacres and killings, and renewed the word genocide. Since February 9, 1995, the route that the State traces is to contain militarily, besiege and, above all, systematically betray its agreements and commitments. It grants the indigenous people the status of enemies of the State. In June 1995, we saw the first blow in Aguas Blancas, Guerrero. [2]

Thus, a fratricidal counterinsurgency is methodically constructed among Chols in the northern zone of Chiapas, while dialogue with the rebel comandantes in the Tzeltal jungle and in San Andrés Larráinzar. The dead are piling up to block the dialogues, but in April 1996 the first few agreements were signed. Participation in the dialogues of representatives of the indigenous peoples from all over the country was notable. Whether the government liked it or not, the issue was national and had to be reflected in the Constitution. Zedillo decided not to comply, blatantly. He sharpened the counterinsurgency and extended it to Chenalhó in the Tsotsil region. More deaths, until reaching the Acteal Massacre on December 22, 1997, and then, during 1998, the deaths of El Bosque right there in Los Altos, El Charco (Guerrero again) and the offensive against the Zapotecs of the Loxichas region in Oaxaca.

It turns out that the Indians matter, and to the State but not for the best reasons. Again and again Zedillo attempts to pass over them, ignore them, deny them. He leaves Chiapas militarized and delivers the government to twelve years of the confessional right, even more impotent for confronting the challenge of the indigenous peoples. However, the “war” against organized crime unleashed by Felipe Calderón Hinojosa in 2007 has as its first effect militarily and para-militarily cornering, not just the rebels of the south and southeast, but also a good part of the Native peoples. That paralyzed self-government projects and national movements like the National Indigenous Congress (Congreso Nacional Indígena), founded in 1996 under Zapatista inspiration. Few perceived it, the media didn’t record it: Calderón achieved reaching 2010 with the country in flames and the Indians cornered. In Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Chihuahua and Chiapas community members continued dying, and the hundred-year anniversary of the Mexican Revolution could not be the bell ringing that many expected, somewhat like 1992, when the celebratory failure of the 500 years stirred the definitive eruption of the continental indigenous peoples.

A quarter of a century after the Zapatista Uprising, and in view of its innumerable consequences, it’s evident that much has changed. The peoples rose up in the cultural, organizational, symbolic and even the linguistic sense. Since the beginning of the 21st century, a feverish literary writing in Mexican languages has been unleashed in the country, with works and authors that deserve a place. That didn’t exist 25 years ago, nor was it predictable. Literature as a sign of life!Today, the State presents itself as liberal as those before, nationalist, and once again encounters the inescapable stone of the indigenous peoples, their rights, territories and their own governments. Andrés Manuel López Obrador promises to develop, not repress; to consult, not impose. For him, the poor are first, and as the Indians are “poor” par excellence, then the Indians first, who would stop being poor. It’s just that the State’s projects and the global capitalist tendency continue demanding that they stop being Indians: language and embroidery as folklore, without territory or their own government, as always. But it’s been 25 years ago that to the Native peoples things stopped being “as always.”

—————————————————————

Originally published in Spanish by the Revista de la Universidad de Mexico in its Abya Yala Dossier (The University of Mexico Magazine), April 2019. The original can be read here: https://www.revistadelauniversidad.mx/articles/86c78d97-8a18-4088-bdde-0f20069ec0ef/zapatistas-una-transformacion-de-25-anos

Re-published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Translator’s Notes:

[1] Authentic coletos are residents of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, who were born and raised there. They strongly opposed the Liberation Theology of Bishop Samuel Ruiz García and his consequent “option for the poor” and actively organized against him.

[2] On June 28, 1995, the Guerrero State Police massacred 17 campesinos from the Organización Campesina de la Sierra del Sur (Southern Sierra Campesino Organization) at a place called Aguas Blancas.

Editor’s note on the Background: “Zapatistas, A 25-year transformation,” from 2019, by Herman Bellinghausen reflects on the long liberation struggle of Indigenous people marked by the 25th anniversary of the Zapatista uprising. In 2021, the EZLN is in the 27th year of struggle and organizing. Bellinghausen’s piece provides analysis and background to understanding Zapatismo. This is especially crucial in this historic year, when they EZLN has announced their initiative to take Zapatismo across oceans and continents. The Chiapas Support Committee will occasionally publish longer pieces to help us learn and reflect on the roots and history of Zapatismo and to dialogue and to deepen our imagination and our own way of thinking and organizing on U.S. terrain.