Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

The wetlands in San Cristóbal, Chiapas, are worth more than a billion pesos and a city’s water

By: Ángeles Mariscal

The La Kisst and María Eugenia Mountain wetlands, located in the municipality of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, are at risk of disappearing. To assess the cost of the loss to the ecosystem services it now provides, and propose the recovery strategy, the federal government’s National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change (INECC) made an economic diagnosis of what this area provides to the population of this region.

The Kisst and María Eugenia mountain wetlands occupy 347 hectares and are located in the southern part of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, the main tourist attraction in Chiapas and one of the most emblematic and important colonial cities in southeast Mexico.

This area captures and stores carbon and regulates the temperature of the region. It houses species of fish, birds, amphibians and endemic mammals classified for special protection. It also prevents flooding by stopping soil and sediment entrainment, provides recreational services and scenic beauty and provides water to the population of San Cristóbal’s around 123,000 inhabitants, explained María del Pilar Salazar Vargas, Director of Environmental Economics and Natural Resources.

In the economic valuation of these ecosystem services, the INECC details that, for example, the capture and storage of carbon that is carried out in these wetlands, in the carbon market has a cost of 41 million pesos per year; flood control is just over 67 million; providing clean water has a value of 198 million pesos; and providing water to the entire population costs 769.98 million pesos. That is, wetlands provide services that in monetary terms mean 1 billion 77 million pesos each year.

But, according to the INECC study, the place is affected and 86% of its service potential was lost, mainly due to water pollution from fecal waste and other waste that is dumped there; but also due to the extraction of stone material and the pressure that real estate [interests] -many of them linked to tourism- exercise, in addition to the invasion of individuals, who have built houses on top of the wetlands.

This meant that, in April of this year, the federal government decreed the wetland zone of San Cristóbal de Las Casas as a “critical habitat” – the first to be decreed in the country – which allows immediate and urgent strategies to be established for the recovery of the place.

Agustín Ávila Romero, General Director of Policies for Climate Action of SEMARNAT and the one in charge of the General Directorate of INECC, explained that in the strategy that is already applied in the region of these wetlands. They established areas of operation, one of them of maximum protection, where no activity that affects the preservation and recovery of wetlands will be allowed, such as as new constructions.

INECC officials acknowledged that any conservation and recovery project in that area is a challenge due to the social dynamics that are now experienced in that city, including “the interests of criminal groups in the area.”

In the maps they presented, they locate three points of the wetlands in which the social dynamics are more complex: the Bienestar Social, Fracción San Cristóbal and San Pablo districts, where the population that carries out conservation actions, as well as the authorities, have suffered physical aggressions.

The problem is such that they have not been able to stop the trucks that take out stone material, “application of the law is lacking,” explained Ávila Romero.

Finally, the specialists explained that recently at the COP27 held in Egypt, it was agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 35% by 2030, “this entails a set of measures where we have to understand that wetlands are key to combating climate change,” and thus the urgency in attention to the wetlands area of San Cristóbal.

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Thursday, December 15, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/12/mas-de-mil-millones-de-pesos-y-el-agua-de-una-ciudad-eso-valen-los-humedales-de-san-cristobal-chiapas/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work for the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

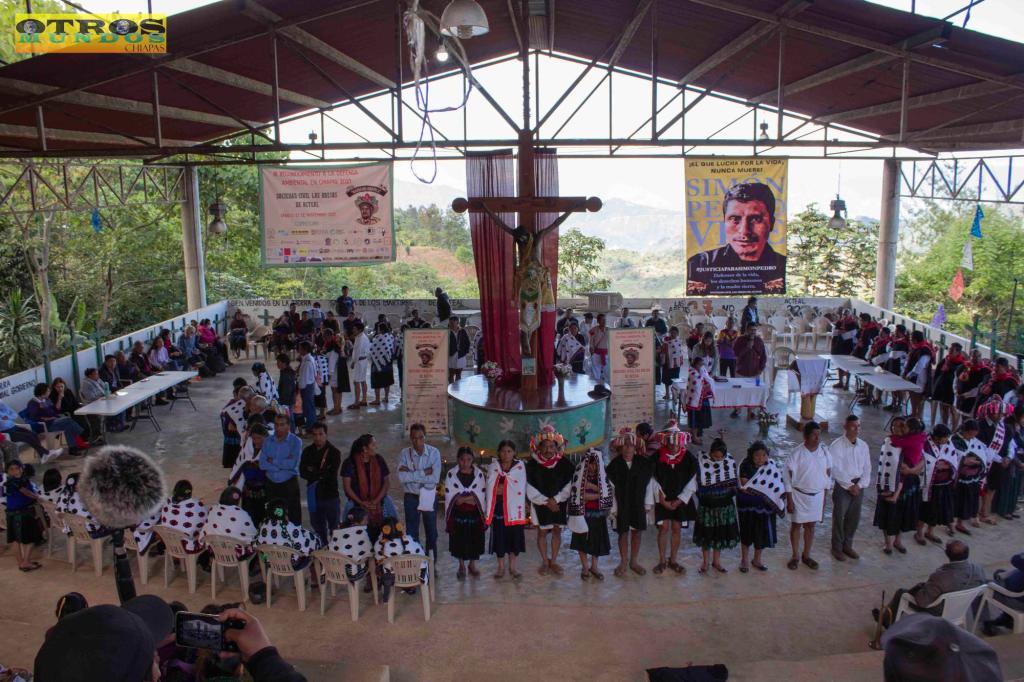

They commemorate the Acteal Massacre with a procession and 45 black crosses

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

Acteal, Chiapas

In front of “the sacred mountains as witnesses,” the survivors and heirs of the victims of the massacre that occurred here 25 years ago stated that they have always struggled “for a dignified and just life,” and their heart “is a guardian of the memory of our own history and walking as peoples.” The civil society organization Las Abejas, to which the 45 Tsotsiles who were murdered by paramilitaries belonged, also celebrated the 30th anniversary of its founding in December 1992.

The organization’s message, read by Guadalupe Vázquez, survivor as a little girl of the massacre and current symbol of the peaceful struggle and demands for justice, adds: “Our heart, like a monument, preserves the tragic event of the Acteal Massacre,” which took place “within the framework Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan’s counterinsurgency war, designed by the Ministry of National Defense and the PRI government of Ernesto Zedillo.”

Yesterday morning, having previously met at the Majomut sand mine, hundreds of indigenous people walked to Acteal carrying as many black crosses as there were victims murdered 25 years ago. They descended into the ravine that has since been declared the “sacred land of the Acteal martyrs.”

The pilgrims and their companions from the Catholic Diocese of San Cristóbal de las Casas and civil society were distributed on the steps and balcony of the panoramic temple, built on the tombs of the fallen and today sumptuously adorned with flowers, banners, lit candles, a high cross in the center, a modest Catholic altar and portraits of the late Bishop Samuel Ruiz García and the leader of Las Abejas, Simón Pedro Pérez, murdered a year ago by hitmen in Simojovel.

Dominican Bishop Raúl Vera, compañero of Jtatik Samuel Ruiz García in the bishopric at the time of the massacre and current bishop of Saltillo, could not miss the commemoration. For the indigenous people, the brave Bishop Vera, who has always been with them, is their jtotik. [1]

Admitting that: “it would seem that the tragedy has marked us in different ways,” the Las Abejas document states that: “the injustice and abuse of power gave us birth.” It covers the group’s milestones from their struggle for the release of their political prisoners in 1992 to the present day. The “State crime” remains unpunished: “as we have been denouncing month after month for a quarter of a century, the governments, be they PRI, PAN or Morena, instead of applying justice, have created strategies and policies of attrition (wear and tear) towards our organization. That has been their custom for burying truth and justice. The only thing that characterizes us is the tenacity and stubborn long-term memory that we have woven.”

It highlighted the attrition strategies and policies of successive governments, in particular that of Felipe Calderón. Another strategy “has been the procrastination of justice that has caused two divisions in our organization, in 2008 and 2014.”

Impunity has caused “endless conflicts in Chenalhó communities.” The municipality “has been ruled by violence” since 1997. “Impunity for the massacre has not only brought sadness and decomposition of the social and community fabric, but has caused unimaginable violence throughout Mexico. Not only can we say that the Mexican justice system is rotten, but that it is going from bad to worse. It seems that paramilitaries and organized crime have allied themselves.” Las Abejas mentioned Samir Flores Soberanes and Simón Pedro Pérez López.

In another message, the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba), a historical defender of Las Abejas, said: “It’s inspiring to observe how they build an island of peace and hope in everyday life, a refuge from the storm that surrounds the Los Altos (Highlands) region of Chiapas, where bullets fall like permanent drops and the social fracture widens amid the collusion and inaction of governments.”

Frayba pointed out that “the current federal government has maintained silence and denied before the Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights the involvement of Mexican authorities in counterinsurgency actions during the 90s in Chiapas, and has consciously excluded this period from the study process of the Truth Commission.”

Finally, Dr. Adriana Ruiz Llanos, of the Intercultural Health Support Network in Acteal, denounced “the incompetence of the Chiapas authorities to attend to victims of violence.”

[1] jtatik means Father in Tseltal and jtotik means Father in Tsotsil.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, December 23, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/23/politica/007n1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work for the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

Peru, the language of the street

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

The street is talking in Peru. And it does so loudly. From the farthest and deepest corners of its geography to the megacity of Lima, it cries out for the closure of Congress, for new general elections, a constituent assembly and for the release of Pedro Castillo.

Street struggle has a long tradition in the Andean country. It has defined crucial issues on multiple occasions. A large archipelago of popular movements has flourished demonstrating along avenues and sidewalks, blocking roads, taking charge of their self-defense in Campesino Rounds and facing the devastation perpetrated by open-pit mining.

The ongoing call for the popular insurgency is the daughter of the political crisis caused by Castillo’s announcement, less than 500 days after assuming the presidency, that his government was proceeding to “temporarily dissolve the Congress of the Republic and establish an exceptional emergency government,” which would govern by resorting to decree-laws until the installation of a new Congress. and his almost immediate arrest and replacement by Vice President Dina Boluarte, with the approval of the United States and the Organization of American States (OAS).

It is also the product of an endemic political crisis. In four years, six presidents have governed Peru (Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, Martín Vizcarra, Manuel Merino, Francisco Sagasti, Pedro Castillo and Dina Boluarte). The current social emergency originates, in part, in the exhaustion of the regime that emerged in 1993 and its outdated Constitution. There is not only a permanent struggle between Congress and the Executive, but also a lack of political representation of huge sectors of the population.

Historically, the Sindicato Unitario de Trabajadores de la Educación en Perú (SUTEP), the education workers union, has been key in forging the left-wing social force that has taken to the streets over five decades. Its members – some 800,000 teachers – are all over the territory. The invisible fabric of internationalism led SUTEP to establish a close relationship with Mexican teachers in the mid-1970s who, in 1979, founded the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE).

Emerged from SUTEP, Professor Pedro Castillo led a split from that union in 2017 to found the National Federation of Education Workers of Peru. He then formed the Magisterial and Popular Party of Peru, as one of the electoral tools that allowed him to win the presidency.

The rural teacher Castillo was born into a peasant family. His parents were illiterate. He was never a deputy or minister. Coming from progressive evangelism, as a leader of SUTEP he led one of the longest and most important strikes by Peruvian education workers in 2017. In 2021, the teachers became the backbone of his electoral campaign, in which he visited the communities where political parties do not reach, with a huge pencil as an emblem.

In a markedly racist country, the teacher won the presidential elections in the second round, articulating the social left, indigenous peoples and social sectors not identified with the political system. He offered, for example, to convene a constituent assembly and push for land reform. He defeated the neoliberal kleptocracy headed by Keiko Fujimori, also endowed with an important social base, built during the dictatorial government of her father, around the fight against poverty.

However, beyond the victory at the polls, it soon became clear that Castillo won the presidency, but not the power. He remained in a minority in Congress, did not have the support of either the army or the judiciary, and faced the animosity of the press and the great potentates. Events followed one another quickly. On two occasions, Congress tried to remove him. They did not reach the 87 votes they required.

Faced with the attacks of the right, far from resorting to those who brought him to the presidency, Castillo isolated himself from them. He bowed to pressure from the right and got rid of the best men and women in his cabinet. He set aside the call for a constituent assembly, early elections, land reform and the fight against open-pit mining. As if that were not enough, he called on the OAS to mediate in the pulse he maintained with Congress.

Despite the corruption allegations against him, at the time of the coup he had an approval rating of 31 percent, while Congress had only 9 percent sympathy. On December 7, right-wing legislators had forged a new attempt at a legislative coup, for which they did not have enough votes. However, the president’s failed call to dissolve Parliament precipitated his downfall.

The response of the nobodies against the right-wing coup has been of impressive vigor. Deep Peru speaks with indefinite strikes, caravans, demonstrations, road blocks, burning police barracks, airport takeovers, clashes with public forces. The popular insurgency is underway.

What future will this explosion of the invisibles have? Can it precipitate an early call for elections (not the mockery announced by Boluarte) and a new constituent assembly? Will a state of emergency be declared? Will she be drowned in blood and fire? Regardless of the outcome it has, as happened 151 years ago, when the Parisian comuneros took to heaven by storm, the popular insurgency that today speaks the language of the street in the homeland of José Carlos Mariátegui deserves our solidarity and support.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, December 13, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/13/opinion/019a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Acteal infamy, 25 years in memory

By: Hermann Bellinghausen*

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas

A quarter of a century ago, on December 22, 1997, the direst of omens were fulfilled for the communities of Las Abejas and the support bases of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in the Chiapas Highlands: 45 people from the pacifist civil organization Las Abejas [The Bees] were brutally murdered in a few hours by a paramilitary group that had already been fully identified.

The massacre was never forgotten. Not only for the survivors, who for 25 years have taught the country what it is to resist peacefully and demand with dignity. Nor for the indigenous people of all Mexico nor for millions of people in the world. Acteal occupies an important place in the universal calendar of infamy, paraphrasing Borges.

Chiapas had two years of increasing paramilitary violence in response to the Zapatista uprising, officially disguised as “intra or inter-communal” or because of “religious differences.” In 1995, the Development, Peace and Justice group was unleashed, an allegedly civilian organization, soon paramilitary, related to the Mexican Army, widely deployed in the northern zone of the Choles, and greatly benefited by government programs.

In 1997, the paramilitary activity was unleashed in Chenalhó, And, starting in May of that year, the story was one of murders, houses and plots looted and burned. The people involved had been denounced for bringing firearms into certain communities tolerated by police forces and military checkpoints. Soon, thousands were displaced, completely dispossessed, in the rainy winter of 1997. Las Abejas and Zapatista bases established camps in Acteal and Polhó. Murders and executions paved the way for the massacre.

You didn’t have to be too suspicious to “smell” what was coming. Which by early December of that year, seemed imminent. However, the facts were beyond imagination. When Gonzalo Ituarte, of the diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, communicated to the Secretary of Government of Chiapas, Homero Tovilla Cristiani and his undersecretary Uriel Jarquín, the reports of shootings in the camp for displaced persons of Acteal, they promised to “investigate.”

It was 2 p.m. on Monday, December 22. At 6 p.m., Tovilla Cristiani notified Ituarte that the situation was under control and only “a few shots” were heard.

Attacked from behind

At the same time the first Red Cross ambulances arrived with the wounded survivors of those “few shots.” The State’s responsibility in the crime was enormous. “Its” people attacked from behind and shot indigenous people who were praying or crying. Bullets and machetes courtesy of the government of Ernesto Zedillo, through the obedient path of Governor Julio César Ruiz Ferro and the counterinsurgency cunning of General Mario Renán Castillo, in command of all federal troops in the so-called “conflict zone.”

It took 23 years for the federal government to recognize the responsibility of the State in the massacre, in the voice of the undersecretaries of the Interior Alejandro Encinas and Martha Delgado Peralta. Today, the demands for justice of the historical organization of Las Abejas still stand; they have decided to wait for the verdict of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which accepted the case in 2005.

*Hermann Bellinghausen wrote the book that exposed the facts about the Acteal Massacre.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Thursday, December 22, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/22/politica/010n1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work for the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

To gaze without seeing, to think without feeling: the limits of eurocentrism

By: Raúl Zibechi

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the consequent war between powers is having profound effects on critical thinking and movements, but in a divergent way in the North and in Latin America: differences and distances are deepening in the ways of conceiving and practicing anti-capitalist transformations, as well as ways of thinking about reality.

In the history of critical thought, war and revolution have been intertwined, to such an extent that it’s almost impossible not to relate the second to the first. Maurizio Lazzarato’s recent book, War or Revolution. Because peace is not an alternative (Tinta Limón, 2022), recovers the concept of war that, in his opinion, had been “expelled” by critical thinking in the last 50 years.

The core of his work returns to Lenin’s 1914 proposal, in the sense of “transforming the imperialist war between peoples into a civil war of the oppressed classes against their oppressors. “He argues that the great problem has been, in parallel, the abandonment of the concept of class, as well as that of war and revolution. And he assures that the current situation is very similar to that of 1914.

This is a first and decisive difference: on this continent, war is present and cannot be hidden, in particular against indigenous and black peoples, peasants and inhabitants of the urban peripheries. The “wars on drugs” and the appropriation of territories for extractivism are just the latest version of a centuries-long war against the peoples.

However, the central aspect to highlight is something different. The peoples are facing asymmetrical wars against them, not because they are pacifists, but because a long experience of five centuries convinced them that to survive as peoples they must take other paths.

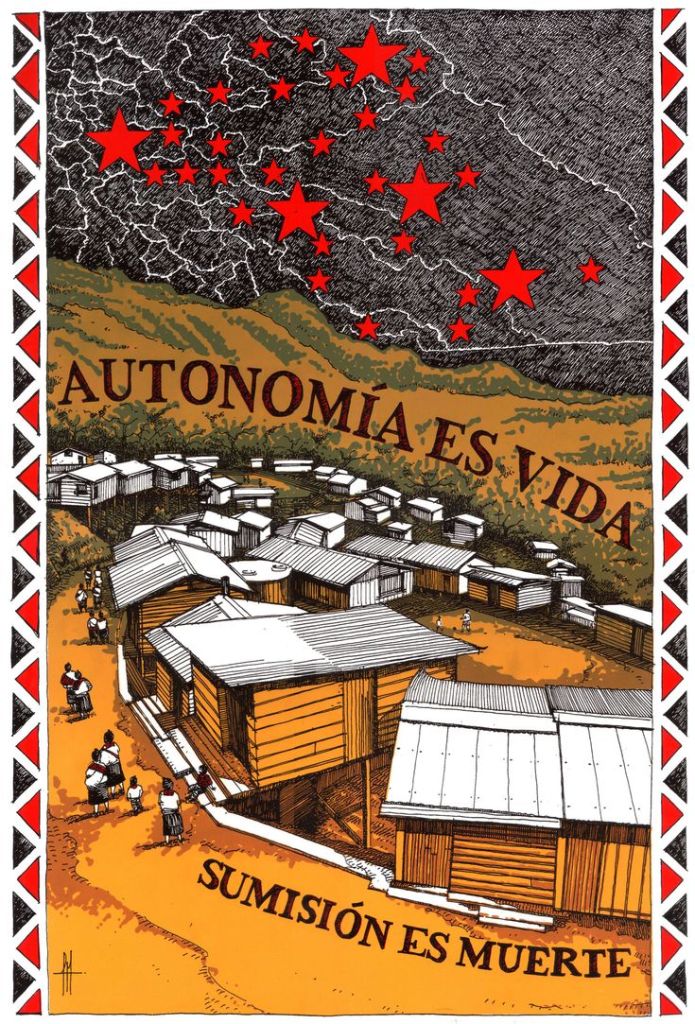

Zapatismo has managed to break the ties that existed between revolution and war and, in the same process, has eliminated its statist adhesions from revolution, to leave its nucleus intact: recovery of the means of production and exchange, creation of new social relations and non-state powers. Autonomies are the way, both to resist the war of dispossession and to affirm themselves as self-governing peoples.

It’s true that the European and also the Latin American lefts have been left without politics, without concrete proposals in the face of war. But the peoples of this continent, experts in surviving the wars of dispossession, are taking unprecedented paths, as do the Mapuche, the Nasa and Misak, the dozens of Amazonian peoples and the black and peasant peoples to face this war. They begin to place autonomy at the center of their constructions and reflections, something that apparently escapes intellectuals on both sides of the ocean.

An additional example of this Eurocentrism that pretends to speak for oppressed peoples, is when Lazzarato points out that “the great merit of the Russian revolution was to open the way to the revolution of oppressed peoples.” He forgets nothing less than the Mexican Revolution and the first Chinese revolution. The deepest processes are born in the peripheries and much later expand towards the center.

It’s not true that during the First World War, “the clearest position in relation to war remains the revolutionary socialist position.” It was very valuable at the time, for the working classes of Russia and Europe. It failed in China, where the communists took very different paths, creating red bases liberated by the peasant army, a process followed by other peoples in the south.

Euro-centrists believe they understand what’s happening in Latin America and consider our struggles as “laboratories” that would confirm their reflections. Some of them feel “theoretically disarmed” in the face of war, but they do not want to learn from the experiences of peoples who have survived five centuries of massacres and exterminations. They only attend to the theoretical production of the academies and the lefts that are referenced in the nation-states, that is, to the coloniality of power.

To me it seems necessary to reflect on how the peoples with Maya roots, who are organized in the EZLN, have disarticulated the revolution-war marriage, which did so much damage to us in the immediate past, and obtained such bad results.

It’s no longer possible to ignore those who were exterminated in the Central American wars, and how the vanguards repositioned themselves in legality, abandoning the peoples they used (yes, used) for their “revolutionary war.”

The decision to deploy peaceful civil resistance to confront the Mexican State’s asymmetric war and extermination is a strategic determination, but it doesn’t have the slightest relationship to pacifism. If I have understood anything about Zapatismo, is that it’s a reading from below, from the peoples, of the challenges that the system is throwing at us.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, December 16, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/16/opinion/019a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work for the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

Join the Chiapas Support Committee on Thursday, December 22, 12:00-2:00pm, in front of the Mexican Consulate in San Francisco, to denounce the capitalist and paramilitary violence and to express solidarity with the struggles of the Zapatista and Indigenous peoples. Details here.

Vigil for Peace & Justice: Stop the violence against the Zapatista communities | Dec. 22 2022

Never again another Acteal

Stop the violence & the attacks against the Zapatista communities!

Join the Chiapas Support Committee

VIGIL FOR PEACE & JUSTICE

On Thursday, December 22, 2022, 12:00-2:00 p.m.

In front of the Mexican Consulate

532 Folsom St, San Francisco, CA 94105

- Raise your voice to pressure the AMLO Mexican government to end the paramilitary violence against the Zapatistas & Indigenous communities and to disarm and dismantle all the paramilitary groups;

- Stand in solidarity with Las Abejas who still are demanding justice on the 25th anniversary of the Acteal massacre; and,

- Join the struggle to defend mother earth: Derail the “Maya” train and stop mega-projects here and in Mexico that are forcing Indigenous people from their lands and territories and contaminating the water, the soil and the air, destroying the natural world.

- If you can’t attend in person, call the Mexican consulate and deliver a message of peace & justice: Stop the paramilitary violence against Zapatista and indigenous peoples. CALL (415) 354-1700

Stop the paramilitary & capitalist violence against Zapatista and Indigenous communities!

The Mexican government has been fueling rightwing paramilitary attacks and violence against Indigenous and Zapatista communities in Chiapas.

The paramilitaries have forced thousands to flee their homes and lands and wounded and killed dozens of people, destroying their crops and livestock, burning down houses, clinics and stores. The escalating right-wing violence reminds people of the conditions that led to the 1997 Acteal massacre.

On December 22, 1997, some 100 paramilitaries attacked and killed 45 Tzotzil people, including women, children and men who were members of Las Abejas, a Christian pacifist group, in the village of Acteal. The paramilitaries sought to crush Indigenous communities suspected of supporting the Zapatista movement. Las Abejas had been founded two years before the 1994 Zapatista uprising. Although they opposed the Zapatista use of force, Las Abejas supported the Zapatistas’s work to build autonomy and regain control of Indigenous lands.

Just as in 1997, when Las Abjeas warned the Mexican government of the growing danger, the EZLN and other human rights and Indigenous land justice groups have been warning the Mexican government that the volatile situation can lead to civil war if the paramilitaries are not stopped.

Along with the paramilitary attacks, the Mexican government mega-projects are destroying the natural world and further displacing Indigenous communities from their remaining lands. The Mexican government also attempts to divide the Indigenous communities from supporting the Zapatista movement for autonomy and land justice.

Join the Chiapas Support Committee on Thursday, December 22, 12:00-2:00pm, in front of the Mexican Consulate in San Francisco, to denounce the capitalist and paramilitary violence and to express solidarity with the struggles of the Zapatista and Indigenous peoples.

Please support our work for Zapatista solidarity by making a generous donation here.

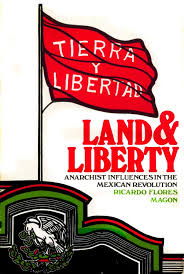

From Ricardo Flores Magón to Julian Assange II

By Carlos Fazio

Released in October 1903 and unable to continue his organizing and campaigning in Mexico, Ricardo Flores Magón went into exile in Laredo, Texas, and then to St. Louis, Missouri, a refuge for anarchist and Marxist dissidents and rebels and anarcho-syndicalist migrants. There he became close friends with the Spanish libertarians Florencio Basora, Jaime Vidal and Pedro Esteve, and the Russian Emma Goldman. He studied and disseminated the works of anarchist theorists, such as Peter Kropotkin and Miguel Bakunin, which radicalized his reflections in the newspaper Regeneración on social transformation in Mexico.

Influenced by methods of the Russian libertarian movement against the Czarist autocracy, Flores Magón proposed a social revolution of the poor by armed means; Mexico could only change through the political-military defeat of General Díaz. From St. Louis, Missouri, he directed the network of contacts of the liberal groups in Mexico, led the formation of the Organizing Board of the Mexican Liberal Party (11/28/1905) and defined its political line. Hounded by US and Mexican agents, he went into exile in Toronto, Canada, and in July 1906 drafted the Program of the PLM (already illegal) and designed the revolutionary insurrectionary project, which included the purging and restructuring of the liberal clubs into a clandestine (conspiratorial) political organization with a centralized command in the junta, preparing the logistical conditions for the uprising (training, stockpiling of weapons) and the publication of Regeneración as a political-ideological and propaganda transmission belt for the fight against the “despot, thief and bloodthirsty Porfirio Díaz.

He participated in the attempt to take Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, joined the liberal insurrection that began with the taking of Jiménez, Coahuila, and went hopping between Los Angeles, San Francisco and Sacramento. When Regeneración was shuttered, Flores Magón and his comrades created the newspaper Revolución. By then Porfirio Diaz was already offering 25 thousand dollars for his capture. In August 1907 Flores Magón was arrested in Los Angeles and was tried for violations of the Neutrality Laws and for conspiracy. He remained imprisoned for 18 months in the penitentiary of Florence, Arizona. In May 1908, President Teddy Roosevelt declared before the U.S. Congress that “the anarchist is the enemy of humanity […] the deepest degree of criminality,” and called for a ban on the use of the post office by anarchist publications, and an increase in the power of the Secret Service. Released in August 1910, in a rally in Los Angeles, Flores Magón shouted: “Long live social revolution!”

In 1910 there was an explosive class confrontation in Mexico: big landowners and capitalists vs. the proletariat and peasantry (96.6 percent of rural families were totally landless). At the head of a vanguard faction of industrialists, landowners, businessmen and northern regional caciques, Francisco I. Madero launched in October the Plan of San Luis, and on November 5 the Liberal Party pointed out its political differences with the Anti-Re-electionist Party. Considering Madero’s armed insurrectionary uprising to be individualistic, it decided to favor clandestine tasks and the reorganization of the party. On November 19, 1910, in Regeneración, Flores Magón reiterated that the two concepts of his slogan “Land and Liberty!” were the essence of the popular demands in the coming Revolution.

The uprising began on November 20. With the help of Standard Oil and some treachery, Madero triumphed, and he asked Zapata and Francisco Villa to disarm their troops. Diaz went into exile. The Magonistas were persecuted in Mexico and the US. On September 23, 1911, in a manifesto, RFM raised the anarcho-communist flag, and supported the revolutionary strikes of peons in Yucatan and the land seizures of Zapata in Morelos, of the Yaquis in Sonora and Chihuahua against Madero’s forces, of the Sotavento towns of Veracruz, and the indigenous communities in Jalisco, and called to take possession of factories, workshops, mines and foundries. For the PLM, the authority and the clergy were the mainstay of the inequity of capital. That is why it declared war on them. And while Zapata established the Morelos commune based on peasant traditions of self-government, the Magonistas established their commune in Baja California according to the anarchist principles of egalitarianism and direct democracy.

In early 1912 Flores Magón criticized Madero’s agrarian policy. And in an article entitled “A Tomar la Tierra,” (To Take the Land) he used the authority of Kropotkin -who supported the Mexican revolution- to insist that land is the basis of all revolution, of the advent of socialism and that “the agrarian problem in Mexico […] constitutes the backbone of the revolutionary movement.” RFM and the PLM supported Emiliano Zapata. There are public documents of the Liberation Army of the South and personal communications from Zapata to Flores Magón.

In issue 262 of Regeneración, which was the last issue, RFM and Librado Rivera published a Manifesto that would cost them their lives. Both were accused of sedition. Considered a dangerous anarchist by the US Department of Justice, Ricardo Flores Magón was sentenced to 22 years in prison. On November 21, 1922, prisoner number 14,596 in the Leavenworth Penitentiary, in Kansas, died under strange circumstances in his cell. He was 49 years old. In Mexico, the defeated revolution would become the ideological banner that would legitimize the government of the bourgeoisie in the 20th century. Today, land is still concentrated in a few hands and the class war continues.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, November 14, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/11/14/opinion/023a1pol Translation by Schools for Chiapas, Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work for the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

Las Abejas of Acteal: Violence against Tzotzils continues 25 years after the massacre

By: Sare Frabes

Last Thursday (10), days before the 25th anniversary of the Acteal Massacre, members of the Civil Society Organization Las Abejas de Acteal demonstrated peacefully to denounce the violence that different communities are currently experiencing in the municipality of Chenalhó, in the Chiapas Highlands.

It was in front of the Chenalhó municipal offices where the indigenous Tzotziles protested against the criminalization of and aggressions against their members. This is the case of families in towns such as Campo Los Toros and Bach’en, who, for the simple fact of belonging to their organization, at different times during 2022, have had their water and electricity services cut.

The Tzotzil organization pointed out that the aggressions come from partisan people from different communities within Chenalhó municipality who violate the rights of Las Abejas families due to their work of denouncing the Acteal Massacre as a State crime.

“We come here in the municipal seat of Chenalhó, to warn the municipal president Abraham Cruz Gómez and his entire city council, not to follow the example and path taken by his predecessor in 1997,” they said during the protest.

Las Abejas contextualized that in October 1997 a commission warned the then PRI municipal president of Chenalhó, Jacinto Arias Cruz, about the paramilitary aggressions against his organization, who ignored the complaints and accused the Indians of “being provocateurs and of being Zapatistas.”

“This mayor of Chenalhó, instead of praying for peace and cooling violence, his paramilitaries were burning houses and firing their high-caliber weapons against Las Abejas whom he later massacred on December 22,” they said about the actions of the mayor who was arrested after the massacre and released in 2013.

Las Abejas de Acteal emphasized that, as in the past, the current events are cases of emergency and gravity, “which can constitute situations of forced displacement as have occurred in the Río Jordán neighborhood of the Miguel Utrilla Los Chorros neighborhood and in the Puebla neighborhood.”

At the same time, they blamed these actions on “PRI and Cardenista paramilitaries who have now switched to the Green Ecologist Party and remain unpunished. They are also bothered by our resistance and rejection of the bad government’s welfare programs.”

That’s why they demanded that the municipal president of Chenalhó and the municipal council authorities restore services to families who have been suffering from the deprivation of their basic rights for months. “The reasons for the cuts of water and electricity made by the partisans, have not only happened in the communities already mentioned, but it has become a recurrent practice to exert pressure and aggression to our peaceful struggle and resistance,” denounced the organization through a statement read at the demonstration.

Denunciations

One of the aggressions indicated is about the imprisonment, on October 14 in the Puebla neighborhood, of Francisco Arias Cruz, a member of Las Abejas who was deprived of his freedom for eight hours and was released after the imposition of a fine of 10 thousand pesos.

Another reported case is that of the Nuevo Yibeljoj community. This town was founded in 2000 after the relocation of families from Las Abejas who were displaced in Camp X’oyep, due to the counterinsurgency war in Chiapas.

According to Las Abejas, in 2008, a group of people from the community were co-opted by government officials to cause division among families. Derived from this situation, the dissident group resorted to procedures to modify the name of the community and currently “denies the recognition and respect of the rights of our comrades to make use of the space to build their meeting house and autonomous school exclusively for Las Abejas,” said the Tzotzil organization.

The indigenous Tzotzils pointed out that the municipal president, as well as his agents use strategies of wear and tear [intended to cause exhaustion in the communities in resistance]. “For example, they schedule a date and at the hour of the meeting they leave us in the lurch, and that has happened time after time. The last time the municipal president canceled an appointment for the case of Nuevo Yibeljoj, he argued that there was a problem in Santa Martha, but in reality, it’s that he has no will to bring peace to Chenalhó,” they said.

Las Abejas de Acteal detailed that since the 1997 Massacre, the people of Chenalhó were divided as a result of the counterinsurgency war of the Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan in the context of the Zapatista Uprising.

The indigenous Tzotzils pointed out that, from then on, the Chenalhó municipal council, “which previously served as authorities who watched over life and had the responsibility of maintaining the respect and balance of all its inhabitants, has now become the simple servant of the bad governments and delivers its people into the hands of Death.”

Originally Published in Spanish by Avispa Midia, Sunday, November 27, 2022, https://avispa.org/abejas-de-acteal-a-25-anos-de-la-masacre-continua-violencia-contra-tzotziles/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work for the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

The Peruvian oligarchy overthrew President Castillo

By: Manolo De Los Santos*

June 6, 2021 was a date that shocked many in the Peruvian oligarchy. Pedro Castillo Terrones, a rural teacher who had never been elected to public office, won the second round of the presidential election with just over 50.13 percent of the vote. More than 8.8 million people voted for Castillo’s program – which included sweeping social reforms and the promise of a new constitution – against far-right candidate Keiko Fujimori. In a dramatic turn of events, the historical program of neoliberalism and repression, transmitted by former dictator Alberto Fujimori to his daughter Keiko, was rejected at the ballot box.

Since that still incredulous day, the Peruvian oligarchy declared war on Castillo. They turned the next 18 months into a period of great hostility for the new president, attempting to destabilize his government with a multi-pronged attack that included a major use of legal warfare. Calling for “throwing out communism,” the National Society of Industries (the oligarchy’s main business group) devised its plan to make the country ungovernable by Castillo.

In October 2021, recordings were made public revealing that since June 2021, this group of businessmen, along with other members of the Peruvian elite and leaders of right-wing opposition parties, had been planning a series of actions that included financing protests and strikes. Groups of former military personnel, allied with far-right politicians like Fujimori, began openly calling for Castillo’s violent ouster, threatening government officials and leftist journalists.

The right wing in Congress joined these plans and tried to remove Castillo twice during his first year in office. “Since my inauguration as president, the political sector has not accepted the electoral victory that the Peruvian people gave us,” Castillo said in March 2022. “I understand the power of Congress to exercise oversight and political control; however, these mechanisms cannot be exercised through the abuse of the right, proscribed in the Constitution, ignoring the popular will expressed at the polls,” he emphasized. It turns out that several of these lawmakers, with support from a right-wing German foundation, had also been meeting to see how to amend the constitution in order to quickly remove Castillo.

The governing class of the Peruvian oligarchy could never accept that a rural teacher and peasant leader could be brought to the presidency by millions of poor, black and indigenous peoples who saw in Castillo the hope of a better future. However, in the face of these attacks, Castillo became increasingly distant from his political base. He formed four different cabinets to appease business sectors, increasingly yielding to right-wing demands to dismiss left-wing ministers who challenged the status quo. He broke with his party, Free Peru, when he was openly questioned by its leaders. He asked the already discredited Organization of American States for help in seeking political solutions, rather than mobilizing the country’s main peasant and indigenous movements. In the end, Castillo fought alone, without support from the masses or the parties of the left.

The final crisis for Castillo erupted on December 7. Weakened by months of corruption allegations, left-wing infighting and multiple attempts to criminalize him, Castillo was eventually overthrown and jailed. He was replaced by his vice president, Dina Boluarte, who was sworn into office after Congress removed Castillo with 101 votes in favor, six against and 10 abstentions.

The vote came shortly after the country received the televised announcement that Castillo would dissolve Congress. He did so preventively, three hours before the start of the session of Congress in which a motion of dismissal for “permanent moral incapacity” due to the allegations of corruption that are being investigated was to be debated and voted. Castillo also announced the start of an “exceptional emergency government” and the convening of a constituent assembly in nine months. He said that, until the constituent assembly was installed, he would rule by decree. In his last message as president, he also decreed a curfew starting at 10 p.m. This, like its other measures, was never implemented. Hours later, Castillo was overthrown.

Boluarte was sworn in before Congress while Castillo was detained at a police station. Demonstrations erupted in Lima, but none massive enough to reverse the coup, which had been almost a year and a half in the making, the last in Latin America’s long history of violence against radical transformations.

The coup against Pedro Castillo is a major setback for the current wave of progressive governments in Latin America and for the popular movements that elected them. This coup and Castillo’s arrest are a stark reminder that Latin America’s ruling elites will not cede any power without a fierce struggle to the end. And now that the dust has settled, the only winners are the Peruvian oligarchy and its friends in Washington.

* Manolo De Los Santos is the Executive Co-director of People’s Forum and a member of the Tricontinental Institute of Social Research.

The article was produced by Globetrotter

Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, December 9, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/09/opinion/025a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

From Ricardo Flores Magón to Julian Assange I

By: Carlos Fazio

100 years have elapsed between the death of Ricardo Flores Magón in the Leavenworth Penitentiary, in Kansas, USA, on November 21, 1922 — where he was serving a 22-year sentence for the crime of anarchism, but formally sentenced for violation of the Espionage Act and the Enemies Act— to the solitary confinement Julian Assange now faces in Belmarsh Maximum Security Prison in London, England, awaiting extradition to the U.S. to face charges of conspiracy and espionage.

This period marks the interval between the nascent US empire of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and its current decline as hegemon of the capitalist system, with one constant: the factional use of US class justice, with the consequent violation of the rule of law and freedom of speech and press.

At the end of the 19th century, weakened by war debts and disputes among liberals, the bourgeois-democratic Mexican state gave way to an oligarchic-dictatorial one, led by Porfirio Díaz, who administered the country as a capitalist reserve for his Mexican and foreign friends. His 35-year dictatorship (1876-1911) developed communications, electrification, transportation, industry and large-scale agriculture through concessions to foreign and national commercial interests, and the use of salaried and forced labor, even company stores. As a veritable praetorian guard of private capital and the state, the elite rural police (los rurales) patrolled the country, while a strong army crushed strikes.

Towards the end of the Porfiriato an important industrial proletariat was emerging with growing class consciousness, which led dozens of mining, railroad and textile strikes between 1906 and 1908. They were stimulated by the illegal Mexican Liberal Party (PLM), officially organized in 1905 by the anarchists Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón and Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, who radicalized anti-clericalism in favor of democracy, and advanced their demands in a peasant and proletarian classist direction, while creating a political-military organization with an anti-imperialist revolutionary ideology, which promoted armed revolts in several states of the country.

Although repressed with great costs to human life, the strikes and these unsuccessful armed actions played a major role in the military victories that ousted Díaz from power in 1910-11. (The strike at the Cananea mine, Sonora, near the US border, repressed by rangers and 2,000 Mexican soldiers, left nearly 1,000 dead, a toll similar to the slaughter of federal troops during the Río Blanco-Orizaba textile strike in Veracruz.)

Through the clandestine newspaper Regeneración, the PLM —also known as the party of the Magonistas– circulated its reformist program in Mexico and the southern U.S., a significant part of which would be incorporated into the 1917 Constitution. The program called for an eight-hour workday, a minimum wage, an end to child labor and an end to latifundia. Its rallying cry: Land and Liberty, was taken up by Emiliano Zapata, a small farmer who had been dispossessed of his land in Morelos. Along with the slogan “the land for those who work it, the Magonistas advocated the protection of the rights of Mexican migrants in the U.S., the end of Washington’s interference in Mexico’s internal affairs and a single presidential term.

In this context we can situate the revolutionary leader Ricardo Flores Magón, born in San Antonio Eloxochitlán, Oaxaca, in 1874, and who emigrated at a young age to Mexico City, where he studied at the National Preparatory School and the National School of Jurisprudence. He was not yet 20 years old when he participated in a student protest against Diaz’s third re-election. His audacity was great when he denounced that the dictator had lost his memory with respect to his famous motto of no re-election and that, due to his obsession to perpetuate himself, the workers were threatened and the peasants lulled with pulque and mezcal to be herded like cattle to the polls. This audacity resulted in his first imprisonment in the galleys of the Belén Jail. [1]

At the age of 27, after dabbling in journalism in El Demócrata [2] as proofreader, and another imprisonment, along with his brother Jesús and Antonio Horcasitas, Ricardo Flores Magón founded Regeneración on August 7, 1900, a publication considered a precursor project of the Mexican Revolution, as well as a reference for the working class of the time in Mexico, USA and Europe, and an emblem of anarchism and Mexican socialism at the beginning of the 20th century. Regeneración was published for 18 years, most of it from exile in the USA, with interruptions forced by censorship, persecution and tyranny. Several times the police destroyed its printing presses, and its editors were jailed.

On February 5, 1901, Ricardo Flores Magón participated in the first Liberal Congress in San Luis Potosí, thus linking himself to the budding political organization of which he became the undisputed leader: the Mexican Liberal Party. At the Congress he expressed his famous statement: “The Díaz administration is a den of bandits.” On his return to Mexico City, the repression of the liberal movement reached him, and on May 21 he was arrested along with his brother Jesús. On October 7, Regeneración published what would be its last issue in Mexico.

After his release from prison, on April 30, 1902, Flores Magón joined the editorial staff of El Hijo del Ahuizote, a satirical publication loaded with political criticism and an anti-re-electionist theme, which through caricature functioned as a double-edged sword: to both inform and to mock the Porfirian dictatorship. On February 5, 1903, a banner was hung from the offices of El Hijo del Ahuizote with the lettering La Constitución ha muerto (The Constitution has died). In the photograph of the moment appears Ricardo Flores Magón. On April 16, the offices of the publication were seized and its editors, among them Ricardo Flores Magón, were incarcerated.

Notes:

[1] The official name of the prison was the National Jail. It stood in Mexico City from 1862 to 1933.

[2] El Demócrata Fronteriza (The Border Democrat) was founded in 1896 by Justo Cárdenas to defend the interests of Mexicans in Texas.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada and republished by La haine, November 3, 2022, https://www.lahaine.org/mundo.php/de-ricardo-flores-magon-a English translation by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee.