Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Zibechi: Why There Is No Anti-War Movement

By: Raúl Zibechi

Concerned about the sliding of the war initiated in Ukraine into a third world war, the Spanish writer Rafael Poch reflects with arguments that are also valid for Mexico, Central America and the rest of Latin America: It is a historical scandal that in Europe, a recidivist continent in this matter, there are still no signs of a popular movement for peace (https://goo.su/7XesEwk).

I do not pretend that all his arguments, as we shall see, are valid for our continent. But let’s go in parts. He considers that the warmongering drift forces us to question ourselves and to review in detail everything that has happened in Europe in the last 30 years. I believe that the same can be said in Latin America, since today’s wars start even before the war on drugs, which undoubtedly raised aggression against peoples to new levels.

Next, he denounces “the blind disorientation of all that ‘right left’ that supports the shipment of weapons to Ukraine,” because without their help the war would be quite delegitimized. Poch argues that in the case of Europe, the cultural dominance of the United States has been observed in recent decades, just when the superpower is experiencing its greatest decline in history. This argument has global reach, since Yankee culture has penetrated deeply into our left, although they continue to raise an anti-imperialist discourse.

This culture defends, for example, imperialist wars cloaked in fights for freedom and human rights, in addition to criticizing dictatorships and defending gender equality, used as a weapon of war against some nations and not as full rights of all people.

But he also criticizes hegemonic journalism, because it has replaced the rationality of questions about resources and interests, about history, tendencies of dominance and geography, with the simplicity of condemning villains. That is, the question of context, so crudely eliminated from current non-debates, is obscured.

Although Rafael Poch’s 30-year historical review in his column Hacia la tercera (Towards the Third) seems accurate, we should add something that he addresses in a fairly general way when he attacks that right-wing left that, among us, is called progressivism and that governs a good part of the region.

Progressivism and the left have played a significant role in the demobilization and depoliticization of societies. In Europe there is no real anti-fascist movement, although the extreme right governs in Italy, it can be a government in Spain, it advances in Germany and in other countries. Nor was there a movement against Jair Bolsonaro in the Brazilian streets, because the left is betting on the ballot box and believes that the protest scares away votes from the middle classes.

When the peoples took to the streets in phenomenal uprisings (Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and now in Jujuy, Argentina), they have done so despite or against progressivism and the leftist parties that, once the flame of protest is extinguished, are preparing to channel it through institutional channels.

In Europe, being in favor of peace is synonymous with being pro-Russian and pro-Putin for that left. In our continent, defending the lives and territories of peoples is tantamount to playing into the hands of the right, as the progressives say. In this way, criticism and obedience to power are discouraged, clear symptoms of the depoliticization that crosses us as a society and that, in the long run, favors the right.

Because being on the left was always synonymous with exercising self-criticism and disobedience to power; never in making calculations about profits to reach power or to continue in it.

In Honduras, progressive President Xiomara Castro adopted the model of Salvadoran Nayib Bukele to combat gang violence. Violence against violence; militarization of society; all power to the police and military; strip criminals of their humanity, when they are from below.

Possibilism and pragmatism are the metastasis of progressivism and the left. Why doesn’t the President of Mexico condemn those who attack Zapatista communities and disqualify those who defend their territories and human rights organizations? Are those who shoot at peoples more defensible than those who only put their bodies, without violence, to defend life?

The communique of the National Indigenous Congress anticipates that we may be facing the preamble of a military and media offensive, to the extent that violence is minimized (https://goo.su/O4cxCtx). When the final stages of an administration are crossed, radical actions can be carried out with less political cost than in other periods.

In any case, we must not lose sight of the fact that the right-wing left came to power to unlock governability, in the face of the powerful activism of the peoples.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, June 30, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/06/30/opinion/015a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Postcards from the war. Part II

By: Raúl Romero*

Tuesday, July 5, 2023, in Nayarit, La Jornada correspondent Luis Martín Iñiguez Sánchez is disappeared. A few days later they will find his lifeless body. Monday, July 10, 2023, in Guerrero, more than 5 thousand people, identified as the social base of the local cartel Los Ardillos, “take” the city of Chilpancingo and kidnap police and officials to demand the release of a transport leader. Tuesday, July 11, in Jalisco, municipal and state police are ambushed and at least six people are killed and 12 others are injured by buried explosive mines. In Mexico, today, we wrote in our last installment (https://n9.cl/e1dmfo), unfortunately we are in a context of war.

To understand the war that we are experiencing in Mexico, it is necessary to understand the old and new modalities in which they are developed. In the literature on the subject, there is talk of fourth-generation warfare, hybrid warfare, full-spectrum warfare, total war, and so on. Wars are not only fought on armed terrain or openly, they are also fought covertly or with “low intensity”, media, economic, commercial. The armies of the national states are now also integrated as regional militias – always at the service of financial centers – or strengthened with private troops, such as those of organized crime. The goal remains the annulment and submission of the adversary, but above all control of the territory and its reorganization to guarantee gains to the occupying force.

Although the warmongering rhetoric was abandoned in the current administration of Mexico, in fact the use of military forces for intervention in this war scenario was reinforced, providing them with legal certainty, social legitimacy, economic power and possession of infrastructure. These measures, together with the use of other concepts such as national security, show that the military will only leave the barracks in times of war.

In the war we are experiencing in Mexico, legal economic corporations intervene that dispute territories and natural resources. These corporations have the forces of the State that guarantee security in the looting of minerals, water and other common goods. The armed forces join this work as a construction company, occupying and reorganizing territories to make them useful to capital. Whether from transnational or national companies, private or from the State, the conquest, reorganization and administration of territories to put them at the service of capital is one of the characteristics of this war.

Another of the actors involved in the current conflict in Mexico are illegal economic corporations, organized crime and their armed groups that have a presence and control in various branches of the national economy. These groups have impressive economic, political and armed strength. They are capable of building their own armored cars, financing political campaigns or imposing candidates, and they have the firepower and technology capable of confronting sections of the army, of detonating car bombs, of disappearing thousands of people, of filling the country with clandestine graves and much more. Criminal corporations have gained presence in the cultural industry and many aspects of daily life, to the extent that they are, for many social sectors, a source of employment, a benchmark for social mobility and even a model of success.

Legal and criminal corporations are strongly intertwined, not only in aspects such as money laundering, or in territorial political control, but also in the use of services. In Chicomuselo, Chiapas, and in Aquila, Michoacán, as well as in other regions of the country, mining companies acquire the services of armed organized crime groups to impose their businesses. Depopulating territories and annulling resistance are also part of the objectives of war.

In Chiapas, this war for territory deployed by legal and criminal corporations is combined with an old counterinsurgency war that the Mexican state left installed against the Zapatista peoples through paramilitary groups, corporatism and social programs. It is in Chiapas where the wars rehearsed in other regions of the world such as Colombia are combined, for the conquest and territorial reorganization of a geopolitically fundamental area, seasoned by the drama of migration that they know well in southern Europe and for other illegal cross-border businesses, and exacerbated by the counterinsurgency war that has not stopped.

The war in Mexico finds a fundamental point in Chiapas. There is already a struggle in which the peoples bet on life with peace, justice and dignity. Zapatismo is an advance of that struggle, that is why we must all demand an end to the war against the Zapatista peoples, which is at the same time the cry to stop the war in Chiapas and throughout Mexico.

*Sociologist

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, July 18, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/07/18/opinion/012a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Indigenous groups demand a stop to the attacks on EZLN communities

By: Jessica Xantomila

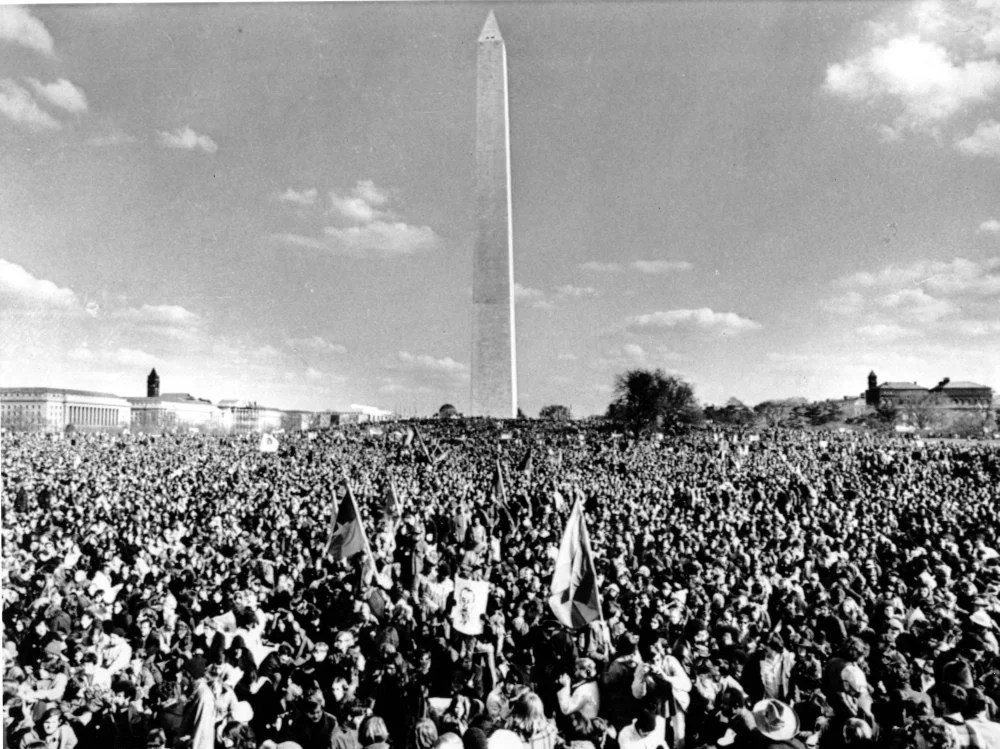

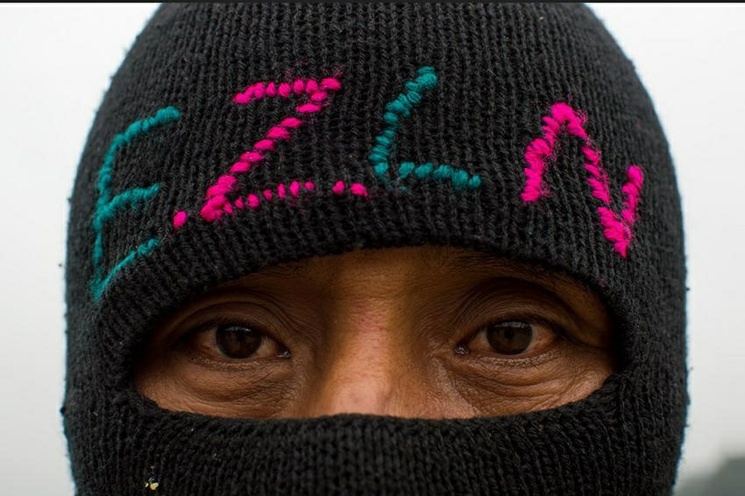

Members of the original peoples of Querétaro, Puebla and the state of Mexico, members of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI), Installed a political-cultural sit-in in front of the National Palace, for about 12 hours, to demand an end to the attacks against the communities of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in Chiapas.

The day of struggle took place within the framework of the Global Action called “From the horror of war to resistance for life,” which was also held in other states, including Baja California, Morelos, Chiapas, Guanajuato and Morelia, and in countries such as Germany, where supporters delivered a letter to the Mexican consulate in Frankfurt.

In front of the National Palace they set up tents in which representatives of indigenous peoples sold handicrafts and held painting and screen printing workshops, as well as the presentation of various musicians.

On the fences that protect the historic site, protesters placed sign and banners with messages “Against all wars ‘art, resistance and rebellion'”, while the slogan Stop the war was written on the pavement.

They condemned the fact that the federal and state governments are minimizing violence against the Zapatista communities.

They emphasized that while the authorities look to nothing, the paramilitaries continue to grow, such as the Regional Organization of Ocosingo Coffee Growers (ORCAO), which besieges our sisters and brothers of the EZLN.

They pointed out that the attacks have left serious injuries like that of Jorge López Sántiz, a support base of the EZLN, whose life was in danger.

Among the participants was Alejandro Torres Chocolatl, indigenous communicator and member of the People’s Front in Defense of Land and Water of Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala, who on June 30 was held for about four hours by alleged ministerial agents of the Puebla prosecutor’s office, accused of closing communication routes and obstructing works in 2019.

Isabel Valencia, from the Otomi indigenous community of Santiago Mexquititlán, Querétaro, said that the peoples suffer the dispossession of water and territory by transnational companies that seem to be the ones who have the reason and the rights.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Sunday, July 16, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/07/16/politica/006n1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

NGOs demand stopping the War against EZLN support bases

By: Elio Henríquez, Correspondent

San Cristóbal de las Casas

Members of various organizations adhering to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle held a traditional Maya ceremony to demand an end to the war against support bases of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN).

“This is a global action that is taking place not only here in San Cristobal, but in the world. These are actions that we have begun to ask for an end to the war against the support bases of the EZLN,” said a woman who spoke.

The Maya altar was placed yesterday at 7 p.m. next to the Cathedral of San Cristobal, where banners were hung to demand that the aggressions against the Zapatistas be stopped.

“This is a ceremony to call for peace, nationally and locally, to ask for an end to the war,” they reiterated in the presence of about 40 people who lit white and colored candles and did a ritual directing themselves towards the four cardinal points.

They added: “From the worldview of the ancestral peoples, this altar symbolizes the energy we want to stop this war and harassment against the Zapatista bases.”

The demonstrators recalled that from June 19 to 22, the Regional Organization of Ocosingo Coffee Growers “carried out new coordinated attacks in three Zapatista communities: Emiliano Zapata, San Isidro and Moisés y Gandhi,” located in the official municipality of Ocosingo.

“Attacks range from the burning of plots to gunfire for three days, accounting for 800 shots of different calibers,” they explained and recalled that on May 22 the indigenous man Jorge López Sántiz almost lost his life from a bullet wound.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, July 17, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/07/17/estados/031n1est and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Testimony before the Inter-American Court: The War Against the Zapatista Peoples

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

AFFIDAVIT BEFORE THE INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS (REF.: CDH-5-2022/027). TESTIMONY FOR GONZÁLEZ MÉNDEZ V. MEXICO

May 2023

I base this testimony on my daily experience as a reporter, permanent envoy of the national newspaper La Jornada to cover the social and political movement unleashed on the new year of 1994 in all the indigenous regions of Chiapas. I lived in the city of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, in the Altos region of the state, from the first week of January 1994 until mid-2014. In that period, especially the first 15 years of my stay, I also spent time in various communities of the Maya villages in the Lacandón Jungle, the Highlands and the North Zone. In some Tojolabal, Tseltal, Tsotsil and Chol communities I came to feel at home, theirs.

My work was to listen to them, witness their events and tragedies, document the evolution of their autonomy and the underground war waged against thousands of communities by the Mexican State, its Armed Forces, its intelligence services, its unofficial versions of the facts, the serious aggressions against the native population of the Chiapas mountains, of Maya and Zoque lineages. I reported this daily in reports, chronicles and informative notes published in La Jornada and often translated into other languages and disseminated abroad.

The movement of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), initially warlike, soon became peaceful, although in resistance, thanks to a fragile truce. The covert and repressive actions of the Mexican Army and the national, state and municipal police corporations put it at risk again and again.

The extension and coherence of the Zapatista movement, composed practically exclusively of indigenous people, with very precise demands, expressed since the first of January 1994 in the Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, was surprising and unusual. Always showing rigorous discipline and sensible control of its firepower, the EZLN had organized support bases in all the official municipalities of exclusively or mostly indigenous population in Chiapas.

The conflict occupied centrally the national political agenda and the government of Mexico. Locked in a chain of denials, falsehoods and half-truths, the State aimed to contain and destroy the rebel movement from the first days of 1994, even during the presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari, and more clearly and profoundly since the beginning of the presidency of Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León, in December of the same year.

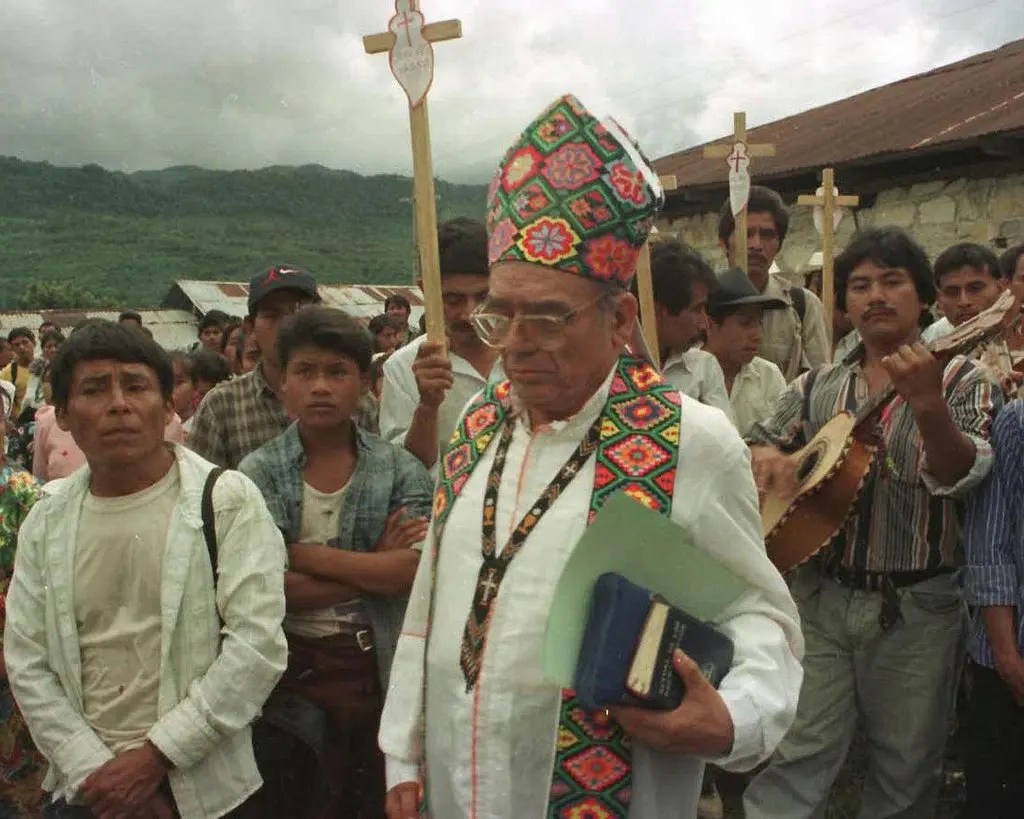

Before arriving at the central point of this testimony, which is the forced disappearance in the municipal capital of Sabanilla of Antonio González Méndez, Chol and EZLN support base, on January 18, 1999, it is worth mentioning how the undeclared, not recognized by the authorities lived daily, the covert war against the Zapatista movement and sympathetic but peaceful organizations close to the Diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, in charge of Bishop Samuel Ruiz García. The latter frequently suffered massacres, disappearances and displacement. But the obvious objective was the Zapatista support bases, seeking to provoke armed responses from the EZLN and annul the truce decreed by the Congress of the Union with the Law for Dialogue, Conciliation and Dignified Peace in Chiapas, in March 1995. Just a month earlier, on February 9, President Zedillo had ordered the military occupation of the newly declared Zapatista autonomous municipalities; that is, almost all the indigenous regions of Chiapas.

The Mexican State, through the Federal Army, launched the Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan (released on January 3, 1998); This establishes the counterinsurgency offensive that will define subsequent events. The true implications of the strategy would be seen over the next five years.

The militarization was direct in dozens of rebel communities, or very pro-government and associated mostly with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), still then hegemonic, camouflaged with the national State, the government of Chiapas and the Armed Forces. For those of us who observed the so-called conflict constantly and in person, a drastic change in the way the state sought to “solve” the conflict became evident. Entering “the heart and soul” of the inhabitants, and “taking the water away from the guerrilla fish,” as dictated by the Pentagon counterinsurgency manuals applied in Guatemala and Vietnam.

Although these strategies were sought to be implemented throughout the area of influence of Zapatismo, not all of them caught on (for example, in the cañadas (canyons) of the Lacandón Jungle). Where the “civilian armed groups” first manifested themselves clearly, an eternal euphemism for paramilitaries, was in the Northern Zone of Chiapas, inhabited mostly by Chol Mayas. In the municipalities of Tila, Sabanilla, Salto de Agua and Tumbalá, the official hegemony of the PRI was transformed into the real predominance of the organization Development, Peace and Justice, which soon began its violent actions.

Some of its top leaders had criminal records in the region since the previous decade; now they became obvious allies of the military command that occupied municipal capitals, roads and indigenous villages. The municipal capitals of Tila and Sabanilla were controlled by Paz y Justicia; the respective parish priests lived practically besieged in their temples and that of Sabanilla, a Spanish citizen, would soon be expelled from the country by the Mexican government.

In other rebel regions, despite militarization, the public presence of the Zapatistas was maintained, who openly guarded territories in resistance, organized around five “Aguascalientes” (Zapatista meeting and self-government centers). In the Northern Zone this was much more difficult, especially after 1995. The violence of the armed civilian group was constantly manifested. Communities in Tila and Sabanilla [municipalities] had to move, fleeing from the looting, rapes of women and executions, under the impassive gaze of federal troops and police forces.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has knowledge of the important reports published by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center and other defense organisms (including the United Nations Rapporteur on Indigenous Peoples). The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) itself has sent in-person observers. There are many details, testimonies and documentation of the events that occurred during the covert war, also called low intensity, “delegated” to armed groups not military or belonging to the federal army.

In August 1995, the San Andrés Larráinzar Dialogues began between the Mexican government and the general command of the EZLN, with the mediation of the National Intermediation Commission (CONAI) headed by Bishop Samuel Ruiz García and the assistance of a commission of senators and deputies appointed by the Congress of the Union, the Commission of Concord and Pacification (COCOPA). On more than one occasion, the tense and delicate talks between the rebels and the government were sabotaged by armed attacks in the Northern Zone, burning of hermitages, deaths and disappearances.

By then the North Zone had become difficult to navigate. It was particularly dangerous for civilian observers, human rights defenders and journalists. With its headquarters in Miguel Aleman, a community in Tila, Paz y Justicia spread terror among the Zapatistas and their sympathizers (vaguely identified as members of the Party of the Democratic Revolution and Bishop Ruiz García’s Catholic Church).

When in my journalistic work I visited the communities and camps of displaced persons in Tila and Sabanilla, I tried to enter on one side and leave on the other, so as not to return to the military, and above all Paz y Justicia’s “civilian” checkpoints. I always thought twice about doing those tours. Between 1996 and 2000, on more than one occasion outside observers were assaulted, even shot. Bishop Ruiz García himself was attacked twice; the second, on November 4, 1997, in the company of Raúl Vera, assistant bishop of the diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

One aspect worth mentioning is the closeness, to say the least, of the highest military command in Chiapas, General Mario Renán Castillo, with Paz y Justicia. A graduate of Fort Bragg and a specialist in counterinsurgency practices, he can be considered the architect of the government’s counterinsurgency plan that deliberately militarized and para-militarized indigenous regions with a Zapatista presence. All this is duly documented in reports that the IACHR has known for years.

Mention should also be made of the subsequent para-militarization of Los Altos, in the Tsotsil region. At the beginning of 1997, the presence of a new paramilitary group became widespread in the municipality of Chenalhó, which was never identified under a precise name. As a contagion from the neighboring Northern Zone, armed civilian groups in visible collusion with federal troops and police forces (both to operate and train and for the transfer of weapons) unleashed a chain of aggressions against Zapatista communities and the Las Abejas Civil Society Organization. The Acteal massacre on December 22 of that same year was a tragedy foretold. Unlike what happened in Tila, Sabanilla, and soon Chilón (where the criminal-paramilitary group Los Chinchulines operated), in Chenalhó journalistic observation and documentation by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (CDHFBC) and other independent organizations were continuous; There were even poignant reports on commercial television. It was no use.

As part of the correspondents and envoys of La Jornada, I covered the events of Chenalhó throughout 1997. Ten years later I published the book Acteal, crimen de Estado (Ediciones La Jornada, Mexico, 2008), recapitulating what happened in Chenalhó that year and the following months. The notoriety of the events, in particular the massacre against followers of the pacifist group Las Abejas, did not prevent the State from hiding and denying its responsibility. The application of justice was limited and ultimately betrayed. The armed group was never disarmed, the perpetrators were not punished, and the application of justice against some operators of the Chiapas state government was insufficient.

In 1998, paramilitary violence spread in Los Altos de Chiapas. In the municipality of El Bosque, the criminal group Los Plátanos operated, openly associated with the federal army and the judicial police. They carried out a massacre in the community of Unión Progreso, this one against Zapatista support bases, while the municipal capital, declared autonomous, was violently occupied by the Federal Army, which at the same time carried out another massacre, in the community of Chavajeval. Since 1997, on March 14, the Army and police forces had carried out the massacre of San Pedro Nixtalucum (El Bosque), murdering four Zapatista civilians and displacing 80 Tsotsil families.

In 1998, the MIRA group operated in the Lacandón Jungle, with relative success. In Chilón, Los Chinchulines destroy homes, rob and murder EZLN sympathizers. Also in 1998, the Chiapas government, supported by such unofficial groups, violently “dismantled” the autonomous Zapatista municipalities of San Juan de la Libertad (El Bosque) in Los Altos, Amparo Aguatinta (Las Margaritas) on the border, and Ricardo Flores Magón in the Lacandón Jungle in Ocosingo.

Somehow, during the period, the action of paramilitary groups, always officially denied, was “normalized.” Between 1995 and 2000, in Tila, Sabanilla, Tumbalá and Salto de Agua, murders became recurrent, including mutilation of bodies, forced disappearances, rapes, the destruction of villages and the forced displacement of hundreds of Chol families. The EZLN establishes new towns, on land recovered after the uprising, for its bases in Los Moyos and other communities in Tila and Sabanilla.

There have been 37 documented forced disappearances, 85 extrajudicial executions and some 4,500 people displaced by the paramilitary group Organization Development Peace and Justice in these Chol municipalities. As highlighted in CDHFBC, the situation is known to the IACHR in case 12.901 Rogelio Jiménez López and Others vs. Mexico.

All this relationship serves to give context to the forced disappearance of Antonio González Méndez, thoroughly investigated by the CDHFBC since then, without the case having received the benefit of justice from the authorities to date.

Antonio González Méndez, a member of the EZLN’s support bases, was responsible for the “Arroyo Frío” cooperative store located in the municipal capital of Sabanilla at the time of his disappearance. This made him a visible figure of Zapatismo, in a town that, as it was already settled, was under the control of Paz y Justicia. Its members governed the municipalities of Sabanilla, Tila and Tumbalá. That is, the municipal police and their investigative bodies worked for Paz y Justicia, in turn openly associated with the occupying federal army.

The alleged perpetrator of the disappearance, a member of Paz y Justicia, has been identified. This has not served to clarify Antonio’s disappearance, and even less to provide restorative justice for his family. Here we find, as in dozens, perhaps hundreds of cases, the repetition of impunity as part of the counterinsurgency pattern. The protection of the prosecutors’ offices when the paramilitary groups acted was evident.

It is essential to emphasize that, to date, the federal government maintains a position in which it denies having developed this counterinsurgency strategy. This immovable denial represents a serious obstacle to the resignification of the victims, the search for truth and justice. In order to make progress in the full administration of justice, it is essential that the Mexican State overcome this position that the facts themselves have denied, which has also been amply documented.

I believe that the forced disappearance and the very probable murder of Antonio González Méndez is part of the operation scheme of the Organization Development, Paz y Justicia. It is in fact one of the last episodes of that atrocious five years in the Northern Zone. With the change of government (and ruling party) in the country and in the Chiapas state at the end of 2000, the belligerence of Paz y Justicia decreases, and even more so when the new state government of Pablo Salazar Mendiguchía imprisons some leaders of that organization, although they are never prosecuted or convicted for their participation in the crimes of the paramilitary organization.

In conclusion, I am convinced that the disappearance of Antonio González Méndez is part of the modus operandi established in the Northern Zone of Chiapas by the Development, Paz y Justicia Organization and its allies, with the direct responsibility of the three levels of government. It obeys the guidelines of the Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan, in the same way as the numerous incidents and violent acts that at that time had been occurring against the communities that were in resistance and con structed despite all their autonomy as indigenous peoples.

Originally Published in Spanish. by Ojarasca, Saturday, July 8, 2023, https://ojarasca.jornada.com.mx/2023/07/08/la-guerra-contra-los-pueblos-de-chiapas-9664.html and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Zibechi: Police in the states, are for dispossession

By: Raúl Zibechi

Michel Foucault considered the police as the permanent coup d’état, a phrase that became famous, although few people fully assume it. The philosopher lived and reflected in France in 1978, when the welfare state was still functioning in what Frantz Fanon called the “zone of being,” where people’s humanity is respected and violence is the exception.

Foucault’s 1978 course, compiled in the book Security, Territory, Population, focuses on the government of the population, the exercise of power that has individuals as its object, to govern the life of each person in its smallest details. The art of governing based on the reason of state consists in “the search for a technique of growth of state forces, by police whose essential goal would be the organization of relations between a population and a production of commodities (p. 386).

It clarifies that the police should not conform to the rules of justice, since their regulations are of a different type from civil laws. The instruments of this permanent coup d’état are ordinances, prohibitions, regulations and arrest, with the aim of disciplining. As can be seen, they are the means that the welfare state developed in the zone of being.

Let’s try a reflection guided by the same logic to understand the police action in the “zones of non-being” (where violence is the norm to resolve conflicts), where States prevail for dispossession, since the 1% kidnapped them to shield their interests. Are we not dealing with policemen who embody the permanent genocide of the peoples of the color of the earth?

Many may be surprised by such an assertion, if not outraged because they continue to consider police violence as exceptional and believe that state institutions are the least bad thing that can happen to a society. Let’s look at some examples.

France’s two main police unions have declared, during riots over the police murder of a young man of Algerian descent, that they are at war with teenagers whom they consider enemies to eliminate, although they refer to them as savage hordes of vermin.

The sociologist Denis Merklen, a researcher in the French and Argentine urban peripheries, considers in a recent interview that these are coup statements and recalls that the police made the Interior Minister resign in 2019 during the rebellion of the yellow vests (https://lc.cx/LomYW). He adds that never before had the police killed an unarmed person by shooting him from a few meters away, as happened with the young Nahel. He was executed, sentenced. Witnesses say the policeman shouted: Don’t move or I’ll put a bullet in your head (https://lc.cx/E3UkpV).

Then it transpired that in the networks a fund was created to support the murderous policeman that raised almost one million euros in a few days, when the initial goal was just 50 thousand. Days later, ultra-right gangs armed with the slogan of lynching blacks and Arabs emerged, thus complementing the police work, already lethal.

The young people without a future who are crowded into huge blocks in peripheral neighborhoods, have not limited themselves this time to burning cars and buildings in their neighborhoods, as in previous revolts, but attacked police stations and occupied the center of the cities, where the privileged classes sleep.

The state was ruthless, putting anti-terrorist units into the streets, such as RAID (Investigation, Assistance, Intervention, Deterrence), although the name designates military assault. According to some media, RAID was deployed in up to 13 cities, considering that the rioters practice street terrorism (https://lc.cx/5rqf0B).

Finally, impunity. Merklen mentions that the ombudsman brought more than 3,000 cases of police violence to justice. Only two of them went to trial, sentence. Nothing happens when those same policemen demonstrate hooded and with their service weapons, demanding again the right to kill, without the political system doing anything (https://lc.cx/E3UkpV).

If this happens in France, we know what is happening in our lands. In Latin America, the police are autonomous, financed by illegal economies (clandestine gambling, trafficking, drug trafficking, among others). In Rio de Janeiro, the militias are the state, as researcher Claudio Alves says. They are heirs of the death squads because, he says, we never left the dictatorship, and today they directly control more than half of the city, while expanding within the State.

This happens in all countries. The police are the permanent genocide of the popular and racialized sectors. We cannot and should not trust state institutions, or those who govern them.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, July 14, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/07/14/opinion/019a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Video: The Caravana El Sur Resiste visits Puente Madera

Chiapas Support Committee members who were on the El Sur Resiste | The South Resists Caravan film an interview with the women of Puente Madera and the elected community authority. They describe their town’s fight to prevent the construction of an Industrial Park on their communal lands. The community is defending its territory and way of life against the capitalist forces that use discrimination, manipulation, and violence to get their way.

You can watch the video by clicking on the links below.

En espanol: https://youtu.be/c4AtDylSwL8.

In English: https://youtu.be/R9MwrFf4xAs

Published by the Chiapas Support Committee, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and an adherent to the EZLN’s 6th Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle

Leaders from Pantelhó’s 86 communities warn they will rise up in arms

By: Chiapas Paralelo

Representatives of the 86 rural communities and the 18 neighborhoods in the town of Pantelhó, asked Chiapas Governor Rutilio Escandón Candenas, and the State Attorney General’s Office (FGE), to dismantle the Los Herrera armed group, because if they do not dismantle it, they will take up arms to expel them from the municipality.

They demanded that the FGE execute the arrest warrants against leaders of an armed group that they say operates in that municipality and has already caused several armed attacks.

In a petition signed by 87 Rural Agents of the administration, 14 Commissioners and Ejido representatives, “as representatives of all the people of Pantelhó,” they denounced some of the violent events that have occurred in that municipality so far this year, and accused an armed group that they said intends to return to impose itself by force of arms.

They pointed out that in that municipality with about 25,000 inhabitants with a population of 95 percent indigenous Tsotsil people, violent events have occurred that have terrorized the civilian population and many of those violent events are attributed to Los Herrera.

They pointed out that on March 1, 2023, a woman named Petrona López Gómez was murdered in the community of San José Tercero, and that for this case the ministerial investigation was practiced by the Indigenous Justice Prosecutor’s Office. “The citizen José Guadalupe Herrera Abarca is presumably responsible for this act.”

On June 3, a man named Armando Pérez Gutiérrez was murdered in the community of San José del Carmen in this municipality. There was no ministerial investigation of this act “and it is presumed that this murder was carried out by José Guadalupe Herrera Abarca’s people,” they accused.

“Last Friday, June 23, at approximately 5 pm in the municipal seat, the citizen who in life responded to the name of Vicente Hernández Ruiz was killed, apparently with a firearm called a shotgun, no ministerial investigation was carried out into this unfortunate act, It is presumed that said execution was carried out by José Guadalupe Herrera Abarca’s people,” the complainants said.

They pointed out that on June 30 at approximately 6 p.m., “an armed group from the community of Tzanebolom municipality of Chenalhó, went to attack the community of San José Tercero municipality of Pantelhó, so that these events left several injured, as well as a dead man named José Velasco Méndez. And, in the same way, there was no ministerial investigation into these acts.”

They reported that “on July 1, at approximately 10 a.m., José Guadalupe Herrera Abarca’s people entered the municipal seat of Pantelhó armed with heavy caliber weapons. They damaged the facilities of the municipal presidency and vehicles that belong to the municipality, with firearms, as well as burning a house. Their armed action that same day caused the death of Gabriel Gómez Gómez.”

“This person was near a gas cylinder and it exploded causing serious burns, so he was transferred to the hospital of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, where he lost his life. His relatives did not want to make any complaint about these acts.”

On the other hand, leaders of the 86 communities pointed out that they “have not yielded to aggressions against the people by the hitmen that José Guadalupe Herrera Abarca commands, who have gone so far as to threaten agents of the communities and neighborhoods that if they do not support him, they will kill their relatives.”

They accused that in addition to Herrera Abarca, another of the leaders of that armed group is Jhovanny Gamaliel Aguilar Moreno, “who is also destabilizing the municipality of Pantelhó, he is always inciting violence.”

Jhovanny Gamaliel Aguilar Moreno is related to one of the 18 who were disappeared by the Los Machetes group on July 26, 2021. Those men were violently taken out of their homes and taken in an unknown direction.

They pointed out that relatives of the disappeared “enjoy privileges from the State Government as direct relatives of the disappeared, consisting of monthly payments for rent, food and cash, when the indigenous comrades who died at the hands of Los Herrera have not received any economic support. And, as they have not procured justice, much less administered it, there are approximately 200 homicides committed to the detriment of our indigenous brothers.”

In addition to Herrera Abarca, Rubén Herrera Gutiérrez and Arturo Ramos Salazar were alleged leaders of that armed group; the latter, they said, “is the one who economically finances the Los Herrera criminal group.”

They pointed out that the founders of the group Austreberto Herrera Abarca and his son Dayli de los Santos Herrera Gutiérrez, are in prison accused of various crimes they committed in this municipality and they did a lot of damage.”

They also denounced that the Herrera group “is allied with the armed group called Los Ciriles, which belongs to the community of Tzanebolom, municipality of Chenalhó. This alliance is in order to destabilize the municipality and thus be able to remove the Municipal Council.”

They said that before “this chaotic situation” the municipality is going through, they decided to meet on July 6 in the Ejido Roblar Chixtontik, with all the communities and neighborhoods that make up the municipality of Pantelhó, where they agreed “that if the Federal and State Government do not take action on the matter, the people of Pantelhó will rise up in arms again and do justice on our own, and we hold the state and federal government responsible for what happens in the town of Pantelhó, for what may happen in the coming days if the state and federal government does not act.”

They indicated that “people do not trust the Government, for that reason they do not make their corresponding complaint about events that take place in the municipality.”

They asked the governor and the FGE (State Attorney General) to execute the arrest warrants that they have in the case against Jose Guadalupe Herrera Abarca, who they say is hiding in Rancho Baltazar.

Leaders of the 86 communities demonstrated their support for Alberto González Santiz, as Councilor President of Pantelhó municipality, with whom they have maintained a little more tranquility, “since from the start of his administration we have seen change in the municipality with public works, as well as attention to the people since he listens to our needs. Therefore, once again we request that you intervene in the matter.”

They denounced that: “it seems that they want to minimize this government that he heads, that nothing happens in the municipality of Pantelhó. In fact, we know that throughout history they have treated us as third-class people and they have also considered us as indigenous people who are worthless and we also know that they have tried to extinguish the state and federal system of government.”

“In addition, the mestizo population of Pantelhó sees us as objects, for this reason we have agreed in assembly that we will defend ourselves as a place and with what we have in our power in order to demonstrate that we are the majority and that we have the full right to do so,” they warned.

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Wednesday, July 12, 2023, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2023/07/advierten-lideres-de-86-comunidades-de-pantelho-se-alzaran-en-armas-sino-desarticula-gobierno-a-grupo-armado-de-los-herrera/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Postcards from the War

By: Raúl Romero

Wednesday, June 28, a car bomb explodes in Guanajuato; in Tapachula, Chiapas, a grenade is thrown at a Secretary of Public Security base. Thursday, June 29, former vigilante leader Hipólito Mora is assassinated in Michoacán. Friday, June 30, Josué Ángel Hernández Salmerón, an active member of the State Coordinating Committee of Education Workers of Guerrero, is assassinated in Guerrero…

Since before they came to power, those at the head of Mexico’s government knew that one of their greatest challenges, if not the main one, would be to solve the problem of violence.

The challenge was not a minor one, and that’s how they undertook it in order to be recognized and remembered as good rulers. Four and a half years later there is no good news.

According to data shown by the President of Mexico on June 14, 2023, from 2019 to that date 153 thousand 941 intentional homicides were registered, which places his government as the highest one in this category; although, according to the same source, a 17 percent drop in this crime is beginning to be registered (https://n9.cl/2qa91).

In the National Registry of Missing and Unaccounted for Persons, since January 1, 1962, there are 111,157 missing and unaccounted for persons as of June 30, 2023. Of these, 42,935 missing and unaccounted for persons have been registered so far during the current six-year term, that is, 38.63 percent of the total registered.

On October 27, 2022, in the morning press conference, the Undersecretary of the Interior reported that up to that date, 63 journalists had been murdered during the current administration, to which should be added the names of six more journalists who were murdered in the following months: 69 journalists in total. If we compare it with the six-year term of Calderón (101), or that of Peña Nieto (96), we could speak of a decrease. But the current six-year term still has 17 months left and, if the trend so far continues, the data could be similar to those of the last six-year term. Let us hope this does not happen (https://n9.cl/viaooj).

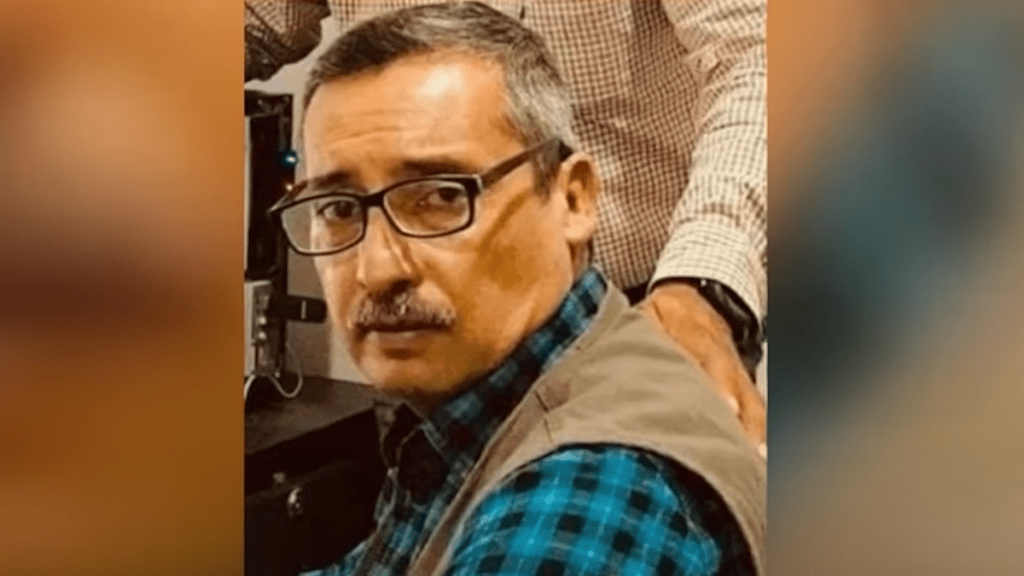

Hipolito Mora, a community leader in Michoacan, was gunned down on June 29th, after years of leading a vigilante defense of his community from the Knights Templar cartel.

According to Centro Mexicano de Derecho Ambiental, from 2014 to 2022 the murder of 148 environmental defenders has been documented, of which 82 occurred between 2019 and 2022. According to this source, these homicides are on the rise: 2019, 15; 2020, 18; 2021, 25, and 2022, 24 (https://n9.cl/cy5it).

We must not overlook other phenomena without precise data on a national scale, such as forced displacement, which, according to the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center, only in the state of Chiapas, between 2018 and 2022, 3,499 people were displaced, both permanently and intermittently, from Aldama; and 5,023 from Chalchihuitán. In Zapatista territory, just in the region of Caracol 10, Floreciendo la Semilla Rebelde (Rebel Seed Blossoming), based in Ocosingo, 150 people have been displaced with the use of heavy caliber weapons by paramilitary-style groups. It is estimated that in the border region of Chiapas approximately 2,000 people (400 families) have been forced to leave their communities due to violence resulting from disputes between criminal groups over territorial control (https://n9.cl/x7vgo).

Violence, qualitatively and quantitatively, has spread throughout the country, and in recent years we have begun to see an explosion in the state of Chiapas that is not only expressed in data, but also in entire communities, being recruited by organized crime, indigenous cartels, private armies and youth addicts of indigenous peoples, ethnic pornography, a phenomenon that we had not seen before in the rest of the country. On top of this, there is the diversification of violence and business: there are paramilitaries, paramilitary groups, narco-paramilitaries that control poultry shops, tortilla factories, transportation systems and many other elements that are fundamental to daily life. Organized crime as an industry has penetrated practically all aspects of cultural and material reproduction in urban and rural areas.

It’s not only a matter of inertia from the past, of narco-governments that ended and everything improved with the arrival of a new administration. There is a diagnostic problem and, therefore, a problem of finding solutions that address all aspects of the situation. There is no peace without justice, it is true, and neither peace nor justice are possible in capitalism.

In Mexico today, unfortunately, we are in a war context, developed at different levels, with different objectives and actors.

This war involves legal economic corporations, criminals and state actors. Criminal corporations have managed to gain ground in mayors’ offices, municipal presidencies, state governments and also in the federal government. In our next installment, some of the characteristics of this war.

*Sociologist

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Monday, July 3, 2023. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/07/03/opinion/019a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Frayba demands the release of an EZLN support base, a prisoner in Catazaja

By: Elio Henríquez, correspondent

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas

The Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba), demanded the liberation of José Díaz Gómez, an indigenous support base of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional), who has been “arbitrarily deprived of his freedom for eight months” in the Catazajá prison.

It said that Díaz Gómez, originally from Ranchería El Trapiche, Salto de Agua municipality, “was arbitrarily detained with signs of excessive use of force, torture, cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment at the time he was forcibly disappeared and held incommunicado by members of the Specialized Police attached to the Jungle District Prosecutor’s Office, who executed the arrest warrant.”

In a statement, it maintained that “the state judiciary has violated his guarantee of due process, accused of the crime of robbery carried out with violence,” since “Frayba documented that on November 25, 2022, José Díaz was arrested at approximately 4:00 p.m., in Salto de Agua and in the company of a relative, he was intercepted by a black van with police agents on board, who showed him an alleged arrest warrant, put him in the back of the pick-up, handcuffed, blindfolded and beaten on various parts of his body. He was dispossessed of 1,400 pesos, his wallet and his credential.”

The Frayba said that the Selva District Prosecutor’s Office “requested an arrest warrant with deficient evidence and without adherence to the principles of efficiency, professionalism and objectivity, in which no further indications were found to assume direct criminal responsibility.”

It reported that the indigenous Chol “is waiting to carry out his intermediate stage hearing, since the Prosecutor’s Office requested deadlines for the complementary investigation since December 2022, but the situation of procedural delay, criminalization and collusion of authorities brings as a consequence the risk of continuing illegally deprived of his freedom for more than a year.”

It demanded that the Prosecutor’s Office “desist from the criminal action against José Díaz, in order to unjustly criminalize him and keep him deprived of his freedom.”

In addition, the Frayba added, “there is an arrest warrant for the same crime against four other indigenous support base members of the EZLN, which puts their dignity and human right to freedom at imminent risk , as a form of intimidation and harassment of Zapatista autonomy.”

On the other hand, the Ajmaq Resistance and Rebellion Network demanded the release of Manuel Gómez Vásquez, an EZLN support base, who “was tortured and violated from the moment of his arrest. He is accused of a crime he did not commit.”

It also demanded the release of Bersaín Velasco Aguilar, Agustín Pérez Domínguez, Juan Velasco Aguilar, Martín Pérez Domínguez and Agustín Pérez Velasco, who are not Zapatist bases.

Originally Published in Spanish. by La Jornada, Thursday, July 6, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/notas/2023/07/06/estados/frayba-exige-liberar-a-base-de-apoyo-del-ezln-preso-en-catazaja/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee