Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Indigenous peoples continue struggling for their rights and survival

By: Carolina Gómez Mena, Fernando Camacho and Jessica Xantomila

After 530 years since the arrival of the Europeans on the American continent, the struggle of the indigenous peoples for their territories and their survival continues, in an atmosphere where the “megaprojects of death and militarization are the new face of colonialism and capitalism.”

Participants asserted the above in the march that took place yesterday in the context of the Day of Struggle for Autonomy and Resistance of Our Peoples, in which they emphasized: “they did not conquer us. We exist because we resist. “

Since the morning, the National Indigenous Congress and the Indigenous Government Council (CNI-CIG), to which Otomi, Triqui and other ethnic communities belong, held a forum at the Samir Flores Soberanes House of Indigenous Peoples and Communities, the former headquarters of the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI).

There they made it clear that the “misnamed discovery of America” is not an ephemeris of celebration, but of protest and resistance.

María de Jesús Patricio, Marichuy, spokeswoman for the CIG, urged “to articulate forces between the various struggles and movements to protect territories and natural resources in the face of megaprojects and militarization.”

After celebrating the second anniversary of the takeover of INPI by the Otomi community living in Mexico City, he accused that capitalism has put a price on land, water and territories, and because of this “they seek to exterminate our communities. “

In the afternoon, the CNI led a march from the Angel of Independence to the capital’s Zócalo, in which some of the parents of the 43 disappeared Ayotzinapa students, searching mothers, students from various universities and members of civil organizations and trade unions also participated.

On the walk various slogans were heard, such as “Christopher Columbus did not discover anything, Latin America was stolen and looted,” “This march is not one of celebration, it is one of struggle and protest,” and “Mexico is not a barracks, Army out of it.”

Although the call was for a peaceful march, a small group of young people with their faces covered painted against the National Guard and the Army, broke glass and vandalized a fast food establishment, without adults arriving. In the National Palace they tried to remove some of the metal fences and rockets exploded.

During the passage of the march along Juárez Avenue and 5 de Mayo, the presence of police elements annoyed some of the demonstrators, who confronted the uniformed men and tried to prevent them from following the progress of the walk.

Around 7 p.m., the contingent arrived at the Plaza de la Constitución, whose esplanade is occupied by the 22nd International Book Fair, so the rally was held in front of the National Palace, which was guarded by police.

In addition to representatives of the CNI, Melitón Ortega, of the Commission of Fathers and Mothers of the Ayotzinapa 43, took the floor, who agreed that the colonization process begun in 1492 continues today with the projects imposed by foreign companies in Mexico and the rest of the continent, regardless of whether the original peoples oppose it.

He pointed out that the current government has not made real progress in the Ayotzinapa investigation case, which makes it “the same or very similar” to that of Enrique Peña Nieto.

University students joined the call to fight against “militarism and capitalist and patriarchal war,” and demanded that instead of giving more resources to the armed forces, that money be allocated to the education sector.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Thursday, October 13, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/10/13/politica/008n1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

From the Maya Train to sympathizers “with a foreign appearance,” Sedena’s constant siege against the Zapatistas

Leaked emails from Sedena (Mexico’s Secretary of National Defense) Have allowed us to know that the EZLN is one of the most besieged by military intelligence due to its posture of rejecting the megaprojects and government programs.

By: Jacobo García

Mexico

Of all the files produced by the Mexican Army (Sedena) from surveillance of potential enemies, including drug cartels, feminist groups, parents of children with cancer or defenders of the land, the surveillance of the Zapatistas of the EZLN is the closest and most detailed.

The information obtained from the massive email leak permits knowing that the Army is obsessed with the bases of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in Chiapas. The follow-up includes detailed fact sheets that include details of events, description of leaders and photographs of supporters. There is also a diagnosis about the future of the group that has allowed us to see the Army’s fixation with an indigenous movement that never fired a shot, but declared war on the State in 1994.

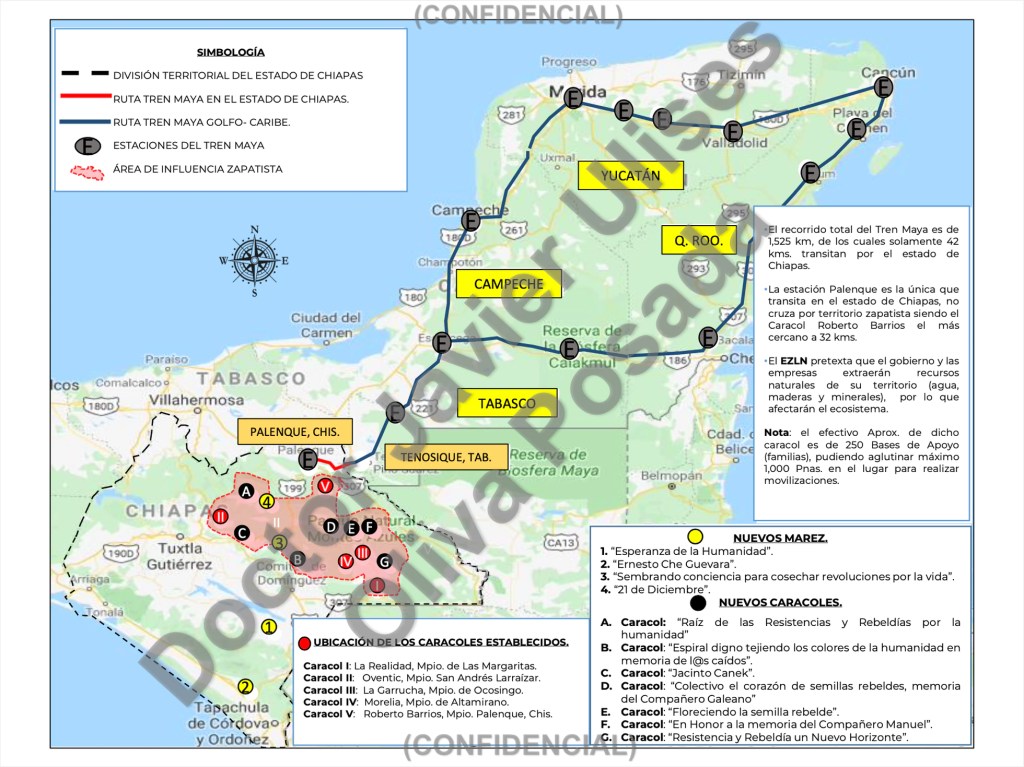

Up to nine different documents give an account of the operation of the caracoles, the movements of Subcomandante Galeano -formerly known as Marcos- or the political activities of María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, Marichuy, presidential candidate in the 2018 elections. Much of the military concern about the Indians has to do with their stance on some of the mega-projects promoted by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. In the document entitled “Position of the EZLN on the construction of the Maya Train”, in January 2020, the investigation that Sedena carried out in the regions with the Zapatista presence trying to find out the way in which the insurgents acted against these works is revealed.

According to conclusions that the soldiers draw from envoys to the event, the assertions of Subcomandante Galeano -identified as Rafael Sebastián Guillen Vicente- that the movement is growing, are false. The lack of economic resources has reduced the carrying of support bases, so that the EZLN will act only by hammering in a national and international public opinion. “When it doesn’t have the power to convene to counteract the projects, only the discourse will be limited and to attack the federal government in a media way for the implementation of these projects, advised by human rights bodies and international observers,” the report said.

The movement’s rejection of said projects is based on the idea that the Government and the private companies will extract natural resources from the territory, including water, wood and minerals, and therefore the ecosystem will be affected. However, according to Sedena, the movement has lost adherents thanks to putting social programs into effect, such as “Sembrando vida,” that have not been to the liking of the commanders, or by the forced contribution of 200 pesos per month per adult, as well as by the monthly family contribution of 10% of the sale of agricultural products.

In another PowerPoint from January of this year, with the motive of the celebrations for the 26th anniversary of the 1994 Uprising, a document was prepared in which leaders, municipalities and activities are described. In one of these documents titled “Activities carried out by militants of the EZLN,” it points out: “Currently, Caracol 2 in Oventic, San Andrés Larrainzar, Chiapas, is the one that represents major relevance, due to the events that they have held and indoctrination activities, which Rafael Sebastián Guillen Vicente (Subcomandante Marcos) attends regularly.

In another document, a Zapatista festival is described as follows: “Date and place: Dec. 26-29. 2019. Caracol IV, Autonomous Municipality 17 de November 17 (Altamirano, Chis.). Activity: “Second International Meeting of Women who Struggle.” They carried out cultural activities (theater, dance, poetry and regional dances). Number of participants: Approx. 3,140 people (760 Zapatista support bases, 800 students, 800 nationals and 780 people of foreign appearance from 43 countries), headed by Antonio Hernández Cruz, aka “Moisés,” current leader of the EZLN and Rafael Sebastián Guillen Vicente, aka “Galeano,” political, moral and intellectual figure of said group. Remarks: Concluded without incident, the file prepared by the military indicates.

The entire document consulted is headed by the word “confidential,” summarizes and outlines the leaders and the location of the autonomous municipalities. It is accompanied± by photographs taken in a hidden way of “Marichuy” and a group of sympathizers “of foreign appearance” or the appearance of Mon Laferte visiting the Zapatista regions. The report includes a map that delimits the area controlled by the EZLN, which includes the municipalities of Las Margaritas, Altamirano, Amatenango, Chilón, Motozintla, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Ocosingo, Palenque and San Andrés Larraínzar, in Chiapas.

Beyond the mountains of Chiapas, in another document found by this newspaper, a military chief of Querétaro Military Camp No.16 sends his superiors a series of files with the profile of the Zapatista leaders in Querétaro. In it, next to the name of the spy, the public or private activities carried out are summarized. In some cases, these cards are limited to writing: “Perform activities of your profession: dentist.”

Originally Published in Spanish by El País, Saturday, October 8, 2022, https://elpais.com/mexico/2022-10-08/la-obsesion-de-sedena-por-los-zapatistas.html?ssm=TW_MX_CM&fbclid=IwAR1dTKyVPsj3Khta9VmPIheRnhIJPMpovABsowvJ-A9fAeIN3HBOCthJWko and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The extreme right took root in our societies

By: Raúl Zibechi

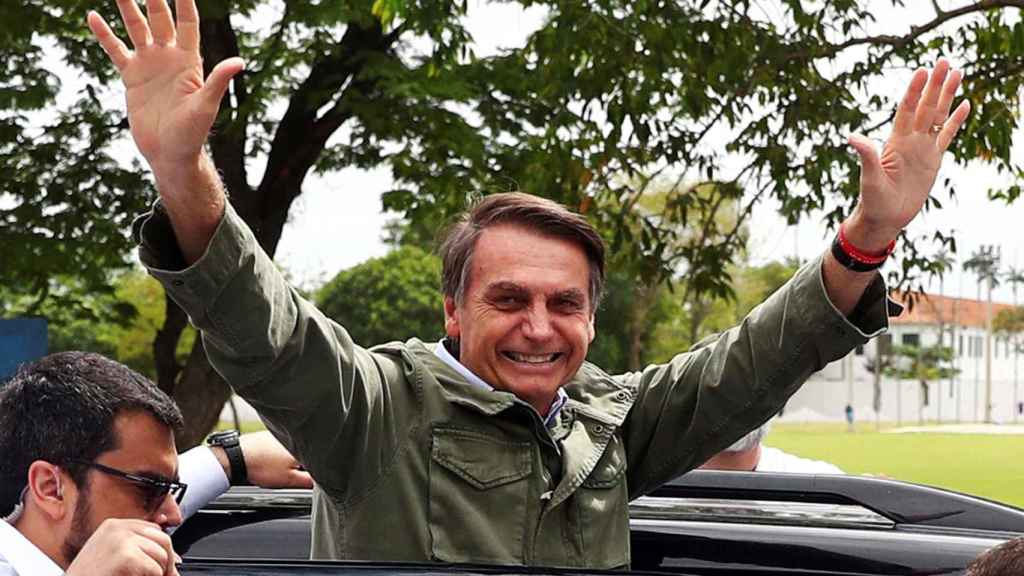

If anyone has the illusion that the extreme right is a passing phenomenon, the first round of the Brazilian elections should convince us otherwise. It’s here to stay, as happens in Italy, the United States, Chile, Colombia and increasingly in countries such as Argentina and Uruguay, where it did not have a solid tradition.

The Liberal Party (PL, Partido Liberal) of Jair Bolsonaro, became the primary political force by getting 99 Deputies and considerably increasing its representation, as well as in the Senate, where it obtained 13 seats. The PT elected 68 deputies who, together with their allies, total 80, and only nine senators.

The Parliament is as rightwing as it was since the 2018 election that Bolsonaro won. Adding the allied parties, Bolsonaro reaches 198 deputies, while Lula could reach 223, if he reaches agreements with some center-right parties. There are 92 seats left out of a total of 513 that, according to the survey of Folha de Sao Paulo, can lean towards whoever offers better positions or facilities to do business.

If the Parliament will be a thorny space that will make Lula, if elected, a centrist president, the ultra-right also took over most of the governments of the states, which play a key role in governability, since they influence the federal and state chambers.

What seems unusual is that after four years of deterioration of the economy, the terrible handling of the pandemic and permanent anti-democratic attitudes, Bolsonaro obtains more than 50 million votes that show a country divided into two halves, a division that will continue after the second round on October 30.

The strong roots of the ultra-right, both in Brazil and in other countries, should make us reflect on its root causes, to operate more efficiently and try to stop this wave.

The first thing to consider is the global systemic crisis that is dismantling the international system of states and the alliances between them. In each region and country, tendencies towards ungovernability and chaos are generated. The dispute between the declining power, the United States, and the ascendant one, China, is a destabilizing factor that favors the generalization of wars between nations.

In this climate, political, social and cultural polarization between classes, skin colors, sexes and generations has grown. Top-down violence is the way in which the ruling classes seek to reshape societies according to their interests, increasingly abandoning any tendency to the integration of popular sectors and peoples. This is an unprecedented challenge for the anti-systemic forces that we are not succeeding in debating and acting accordingly.

The second thing is the tremendous depoliticization existing in societies, the remarkable expansion of consumerism with its burden of alienation and paralysis in the face of the challenges represented by the ongoing crisis/storm. The new capabilities of domination through the most advanced technologies (from social and cellular networks, to artificial intelligence) are not finding answers to the height of the threats posed to humanity.

It’s true that at this point the left has its share of responsibility for having abandoned all anti-systemic attitudes. But if we refine our gaze, we will find that in other periods the left reflected the resistances from below, but did not create them. No one taught the working classes to neutralize Fordism and Taylorism, just as no one taught indigenous and black peoples to confront colonialism, nor did women to confront patriarchy.

Although I wish to be wrong, I believe that it is rebellion itself, a characteristic that has always nested in poor and violated humanity, that today is being neutralized by the ruling classes. Perhaps it is just an urban phenomenon, where exposure to the mechanisms of domination is considerably greater. Perhaps for this reason, our journeys in search of spaces in resistance are mostly towards rural areas, far from the mundane media noise.

Finally, I think that our analyses are too skewed towards ideologies, as if they were the key to explain the growing roots of the extreme-right. But human beings move by issues more linked to real life, although not necessarily by an instrumental rationality. Ideologies come after having taken a position, as a way of justifying and giving flight to what has already been decided.

The powerful spirituality that nests in the peoples who resist, cannot be a coincidence. Sharing spaces and times of celebrations is the mortar of communities, without whose emotional and mystical cohesion it would not be possible to resist or dream of a world different from the one that oppresses us. Spirituality is the common primary of life; but by not feeling it, we are shipwrecked in pure solitude.

Originally Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, October 7, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/10/07/opinion/019a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Frayba: Inaction of the Mexican State deepens violence in Chiapas Highlands

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico

October 5, 2022

Bulletin No. 31

The Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) condemns the acts of violence occurring in the Santa Martha Section, municipality of Chenalhó, Chiapas. According to various sources of information, the confrontations began on September 29, 2022; to date, approximately 129 people have been confirmed as internally displaced (32 families), and are sheltered in the community of Polhó, in the same municipality. Among them are at least 36 children and adolescents in a highly vulnerable situation. In addition to this, approximately six houses were burned and destroyed; at the moment we do not have precise data regarding the number of people injured and killed.

From Frayba we have pointed out the responsibility of the Mexican State in the negligence and continued impunity with respect to the actions of armed groups in the region of the Chiapas Highlands that threaten, murder and displace the inhabitants, which constitutes a continuous and manifold violation of human rights, including access to an adequate standard of living, freedom of movement, freedom of residence, housing, health, education, employment, and a family life.

In various areas of Chiapas there is a crisis of violence, with various civilian actors using armed force as a mechanism for political, territorial and economic control. From 2011 to date, we have documented 40 conflicts where weapons have become the central resource — in 33 of these cases high caliber weapons were used. Half of these events took place in the Highlands of Chiapas, particularly in the municipalities of Chenalhó, San Cristóbal de Las Casas and Oxchuc.

The actors are diverse, ranging from successors to the dynasties of paramilitary leaders who give continuity to the counterinsurgency strategy, in combination with armed groups linked to organized crime and common delinquency, as well as corporatist social organizations linked to the State. In addition, we must also add the militarization of public security in the territories through the presence of the National Guard.

The social decomposition we are witnessing today stems from the unresolved political-military conflict, the absence of effective institutional mechanisms for the resolution of social conflicts, the existence of an illicit arms market, historical impunity and the direct promotion of these dynamics of violence by both local and state authorities.

The violence in these territories is extremely dramatic, as it has touched community structures causing deep and permanent fractures, this because of the mechanisms of terror that are growing, so it is urgent to deactivate the violence and rebuild the social fabric with the participation of the population that resists these criminal actions.

For this reason, we demand that the Mexican State adopt comprehensive measures to prevent the causes of forced internal displacement in the region, as well as to guarantee the protection and security of the people affected to enjoy a life of dignity and peace, in addition to initiating a diligent investigation into the actions of the armed groups in order to dismantle and disarm them.

Originally Published in Spanish by Frayba.org.mx, Wednesday, October 5, 2022, https://frayba.org.mx/la-omision-del-estado-mexicano-profundiza-la-violencia-en-los-altos-de-chiapas/ English Translation by Schools for Chiapas, Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

Chenalhó, Chiapas, the struggle for land via the armed path

By: Ángeles Mariscal

Seven days of constant attacks have passed, without the government being able to intervene to stop the confrontation that is being waged within the Santa Martha Chenalhó armed group, over the possession of 49.5 hectares of land. “If I had no land we would be like beggars,” say those who, now at a disadvantage, have had to leave the town behind and leave behind the dead that this conflict is leaving.

In October 2020, the inhabitants of Santa Martha, Chenalhó, located in the indigenous area of the Altos de Chiapas, managed to get the government to recognize as theirs the 22 hectares they disputed with their neighbors in the municipality of Chalchihuitán; on November 27, 2020, they did the same and obtained 27.5 hectares from the municipality of Aldama. They achieved 49.5 new hectares of land for themselves.

In both cases the dispute over those lands was via the armed path, continuous shooting, constant and with high-power weapons, against their neighbors in Chalchihuitán and Aldama.

Now, confesses a government official, “the serpent bites its tail,” because contrary to official omens, the delivery of land has not brought peace to Santa Martha, located in the indigenous area of Los Altos (The Highlands); now the dispute is between the interior of the armed group over the differences in the distribution of the lands obtained.

This has displaced more than 200 people from Santa Martha, the most recent event has developed since last September 29, and has left an undetermined number of people murdered and houses burned, without as of this moment any government authority having entered the conflict zone.

Defenders of the land

Juan Ruiz Ruiz is assumed to be a “defender of the land.” He explains that he had to fight for the possession of the 27.5 hectares that previously belonged to Aldama, whose inhabitants suffered attacks day after day, until they gave in and agreed to give up part of their land.

Juan says that “defenders of the land pay what is fair,” a kind of fee that Santa Martha authorities asked them to pay for supplies in order to accomplish their purpose.

Once they were gaining ground, they began to sow, which made the authorities of Santa Martha recognize the right to have possession. But in the middle of this year, “the Commissariat and its people began to extort money from us, they began to fine us, until they told us that these lands were not going to be ours, that they had to be distributed. “

The same thing happened with those who had possession of the 22 hectares from Chalchihuitán. They were dissatisfied, and division came about in Santa Martha. On June 25, those dissatisfied with this new distribution of land were expelled from Santa Martha. The men left but their families remained.

On September 29, members of the expelled group tried to harvest crops from the land, and that again detonated the dispute, with a balance so far of houses burned, people killed, shots fired for seven days in a row, and the displacement of entire families of those who had already been expelled.

Total disarmament

Agustín Pérez is another land defender,” displaced from Santa Martha. He says that on September 29, the group they call “the Commissariat,” persecuted several people and murdered an old man also named Juan Ruiz, his wife and children.

Also, his father, who died at home. Then they set fire to the house, with his father’s body inside. He says that in the hours that followed he saw six people die at the hands of this group, and for three days he resisted the armed attacks until he finally fled through the mountains and arrived in the community of Polhó, where there are now more than 200 displaced persons.

“We fought for that land, we paid the necessary expenses,” he laments.

Manuel Gómez Velasco also talks about the fees they had to give to have something to “fight the land” with. “But even though we won it, fines and fines came against us.”

Manuel acknowledges that “the commissariat group accuses us “of being the violent ones, of being the bad guys, but we are not.”

In an interview, Manuel says that they were willing to sign a pact of civility with this group, but this could not materialize. Now, on behalf of the displaced people, he calls for “total disarmament in Santa Martha” and the permanent surveillance of security forces such as the National Guard.

“We have asked for flyovers, but we see that there is no authority. On this day there are still many children and women hiding in the bush, afraid of being killed, without any authority intervening. We want the government to see exactly who is the one with the weapons. What we are asking for now is total disarmament,” he explains.

A new Acteal

José Vázquez survived the Acteal Massacre, which occurred on December 22, 1997, committed by an armed group that was also formed in Chenalhó during that era. Now he, who assumes being a human rights defender and aids those displaced from Santa Martha, says that what is taking place is “a new Acteal.”

“How many deaths does the government want to happen? Who is going to stop this violence? We need there to be a right to life, but there are the dead, there are the displaced, there are the women and children who are leaving the mountain to reach this place,” he says, while pointing to the esplanade of what is the Majomut community’s sandbank, where they set up a provisional camp for people who have managed to leave Santa Martha.

Juan reports that seven days have passed since the recent confrontations. “Right now, there is no control, there is violence, shooting, burning of houses, and the rumor in Santa Martha is that they want to exterminate the displaced, so there is fear in the camp. “

From September 29 to date, those who manage to leave Santa Martha have been arriving at the camp, especially children and women, some pregnant, such as Amalia Pérez Gómez, who is eight months pregnant, and had to walk away among the mountains.

No humanitarian aid from the Chiapas government or the federal government has arrived in this place. As the people displaced left carrying only a plastic bag or a costal with a few belongings, they have just managed to obtain a tarp and some covers to use at night.

Over an improvised campfire, the women prepare some tortillas, that will be their only food of the day. A youth takes the census of displaced persons; yesterday, there were 159, but three new families arrived today; more have sought refuge in nearby municipalities.

The conditions in this camp, the impunity with which armed violence has been exercised and the governmental abandonment -Juan insists- remind him of events prior to the Acteal Massacre.

Some 20 kilometers away, in the municipal seat of Chenalhó, authorities of the three levels of government met with Santa Martha authorities; the latter accepted that security forces led by the National Guard make rounds tomorrow, but only in the downtown area of Santa Martha, they will not let the Guard enter the 21 small communities that make up Santa Martha, and that is where the conflict is taking place.

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Thursday, October 6, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/10/chenalho-chiapas-la-lucha-por-la-tierra-por-via-de-las-armas/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Armed group burns houses, murders opponents, displaces 32 families who flee to Polhó

By: Ángeles Mariscal

This Tuesday marks six days since factions of the armed group that formed in Santa Martha, Chenalhó, in the Chiapas Highlands, have confronted each other. No authority of the three levels of government has entered the place, those who have managed to flee are at least 32 families (127 people), who explained that there is an undetermined number of people killed and dozens of houses burned.

The state and federal governments have maintained their silence on this situation. Unofficially, an official source explained that they broke off all negotiations with this group that had promised to “stop shooting” in order to defuse the armed attacks that at the time were directed against their neighbors in Aldama, but that are now experienced inside Santa Martha, due to differences among the same armed group.

Youtube Video of fire and smoke from burning houses and the sound of gunshots can be heard: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9HEJeCq6vt0

Juan Ruíz was murdered on September 29, the next day his wife and all his children were killed, one of them was saved and was one of the people who managed to warn that in Santa Martha and the communities that make up that ejido, positions over actions that the armed group should or should not carry out have divided them. There are those who never agreed to its articulation, and have been left in the middle of two fires. [1]

From the mountains adjacent to the Santa Martha Ejido you can see columns of smoke that are coming from the houses being burned. “They opened holes in the roads so that no one can enter and no one can leave,” explained one of the inhabitants of the area through a message.

After several hours of hiding and walking in the mountains, those who were able to leave arrived in the town of Polhó, [2] located some 37 kilometers (roughly 23 miles) away, where the population is also divided over the acceptance or non-acceptance of the civilian armed groups, as well as their participation in them.

Also afraid of being attacked, some Polhó residents accepted receiving the displaced families who are little-by-little leaving Santa Martha. They asked humanitarian organizations for aid because they have no way to give food and shelter to the 32 families who until Monday afternoon, had managed to escape the fire. There are 127 people, including girls and boys in arms, who are currently sheltering in a school.

“Those from Santa Martha no longer want to communicate with the government, they say they are going to fix everything in their own way. Their idea is to end the lives of those who do not agree. The families who live here are locked up,” one of the indigenous people of the place narrated through a message. He explained that the clashes continue.

A Pact without disarmament

Santa Martha’s armed group, Chenalhó, came to light on August 20, 2020, when they made public a video in which they are seen in camouflaged uniform, heavy caliber weapons and masked.

In the video they claim as their own 60 hectares of land that their neighbors in the municipality of Aldama have in their possession. The latter (Aldama residents) have lived under armed attacks for the last 5 years.

The siege against Aldama partially ceased in mid-2022, within the framework of the arrival of Esmeralda Arosemena de Troitiño, head commissioner of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), who asked the Mexican government to “commit to arresting those responsible” for the armed attacks against the indigenous population of the area.

Within the framework of that visit, the Mexican government made a pact with the armed group to stop the attacks, and that agreement – which does not include disarmament and disarticulation – is what divided positions within the armed group that is now fighting each other.

NOTES

[1] It would contribute to our understanding of this situation if we knew the organizational affiliation of people with different positions with respect to the civilian armed groups. For example, are any folks in Santa Martha members of Las Abejas, Modevite or Pueblo Creyente? Are they members of a political party?

[2] The town of Polhó has been the municipal seat (or headquarters) of the Autonomous Zapatista Municipality of San Pedro Polhó, a parallel government to the official municipal government of Chenalhó. It is the autonomous municipality that accepted people displaced by the paramilitary violence that culminated in the December 22, 1997 Acteal Massacre. Acteal is located just a few kilometers up the road from Polhó, close to the border with the municipality of Pantelhó.

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Tuesday, October 4, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/10/grupo-armado-quema-viviendas-desplaza-a-32-familias-asesina-opositores-en-chenalho-chiapas/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Chiapas and the Zapatistas face a dramatic increase in violence II

By: Mary Ann Tenuto-Sánchez | Part 2 of 2

Part 1 of this article began to expose factors that contribute to the dramatic increase in violence in Chiapas: 1) counterinsurgency (the government’s “low-intensity war” against the Zapatistas) and 2) two national organized crime groups battling each other for control of the state and local organized crime working with one or the other of the national criminal organizations. Part 2 addresses other sources of violence: 1) the Mesoamerica Project; 2) Municipal Elections and 3) Migration.

The Mesoamerica Project and the San Cristóbal-Palenque Highway

There is a neoliberal effort underway, promoted by the World Bank, to bring indigenous peoples in southeast Mexico into the capitalist marketplace. The vehicle for bringing this about is a massive infrastructure development plan, originally named the Plan Puebla Panama (PPP) and then re-named the Mesoamerica Project.” The name change took place because the PPP was so unpopular and generated so much national and international resistance that it went underground for several years to seek financing and also to make people think it had gone away, but it had not gone away or been forgotten. The PPP simply changed its name and the government stopped referring to projects as part of the unpopular mega-plan.

The Mesoamerica Project focuses on infrastructure projects geared to developing energy, telecommunications, health, cybernetic information and tourism. Two kinds of infrastructure projects that cause controversy and opposition are energy (think dams) and tourism, both projects that displace indigenous peoples from their lands and communities.

The president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, aka AMLO, is implementing the PPP/Mesoamerica Project through infrastructure projects such as the Maya Train, the Trans-Isthmus Corridor, the Dos Bocas Refinery, a new international airport near Mexico City, and other less well-known projects. He just doesn’t say that the projects are part of the World Bank’s plan for developing the Mexican Southeast. Some infrastructure projects AMLO announced specifically for Chiapas include new and improved railway systems, more dams and new highways.

Infrastructure projects completed during prior administrations did not generate controversy or opposition, unlike AMLO’s current project: the San Cristóbal-Palenque Highway, which has created opposition since people first learned about it in the early days of the Vicente Fox administration (2000-2006).

Opposition and resistance to the original highway route led to violence between pro-government folks in favor of the highway and pro-Zapatista folks opposed to the highway, which led to three deaths. The Los Llanos ejido filed a lawsuit against construction of the highway that a court resolved in their favor in 2016. The court’s decision prohibited the government from building a new highway in the municipalities of Huixtán and San Cristóbal de Las Casas, due to the government’s failure to consult with the affected indigenous communities prior to starting construction. This left the government with two options: develop an alternative route or expand the current highway. Initially it looked like an alternative route was selected, but that also met with opposition and resistance from the affected communities.

Consequently, in 2019 AMLO decided that a completely new route for the highway either wasn’t feasible or would take too long to complete. So, he decided to expand the existing two-lane highway between the cities of San Cristóbal and Palenque, and to re-name it the “Highway of the Cultures.” The new plan contemplates expanding the number of lanes on the current highway, the creation of lookout points, small places for the sale of artesanía and elimination of the speed bumps that residents of towns the highway cuts through placed on the highway in order to prevent vehicles from traveling through town at high speeds.

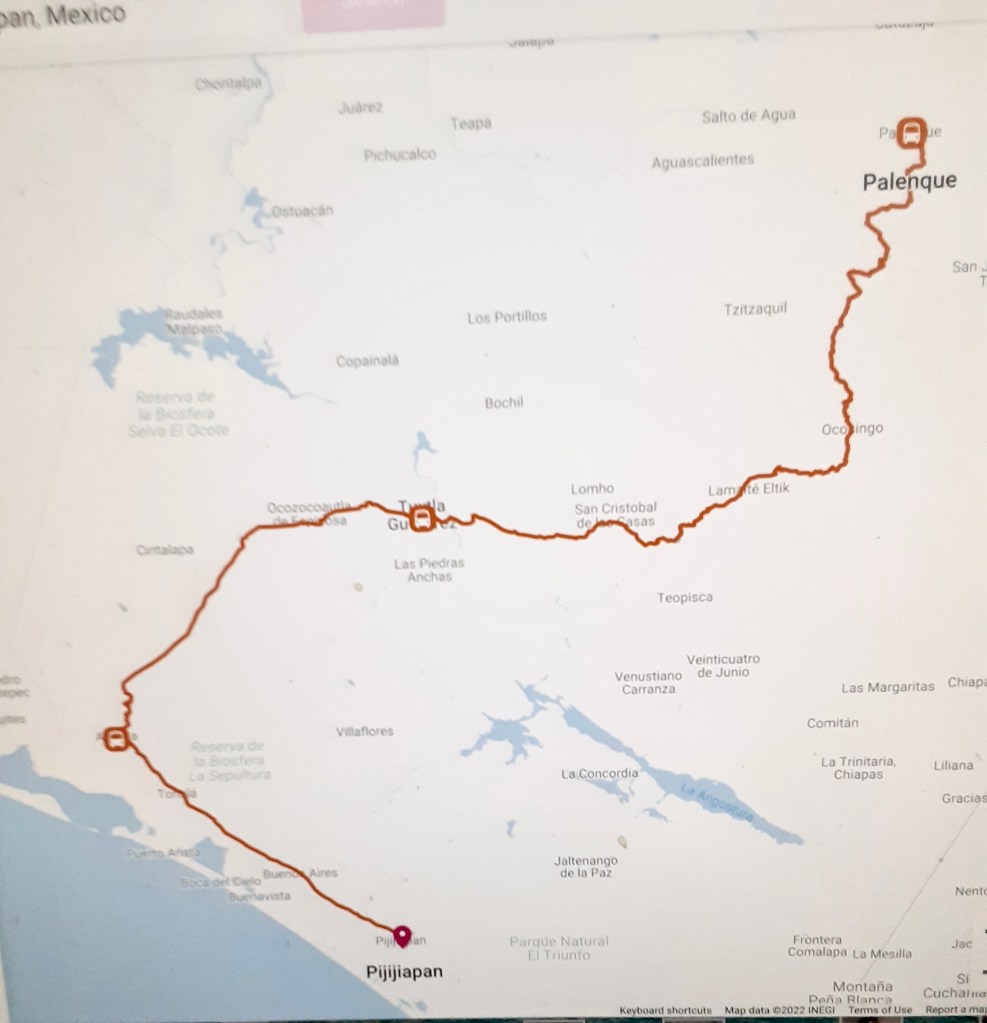

The government’s goal is to attract more tourism by providing tourists a faster and easier way to visit the Agua Azul Cascades and the Palenque Ruins, as well as the Misol Há Waterfall and the Toniná archaeological site near the city of Ocosingo. But that’s not all! Additionally, the Chiapas State Congress has approved plans for a Pijijiapan to Palenque Transversal Highway Axis. The Transversal Highway would provide a superhighway from the southwestern Pacific Coast region of Chiapas to Palenque in the state’s northeast (the Highway of the Cultures would be one segment of this highway). In other words, the Transversal Highway would cut diagonally through the state and cut the driving time in half.

It’s no coincidence that a station of the Maya Train is also being constructed in Palenque. Once the Transversal Highway is complete, double decker tourist buses can shuttle passengers from cruise ships that dock at Puerto Chiapas to Palenque. From there, they can hop on the Maya Train to Cancún and points south on the Riviera Maya. An extension of the Maya Train is also planned northward into Tabasco and Veracruz to connect with the train planned to travel across the Isthmus. The Maya Train project envisions an immense increase in both tourism and commerce.

Organized indigenous communities in Chiapas reject the Highway of the Cultures. It will dispossess their lands and damage Mother Earth, so they protest with signs, marches and roadblocks. Previous attempts to build a new highway have resulted in government repression of protests and violence against protestors by soldiers and police, as well as arbitrary arrests and torture.

Not all resistance to the San Cristóbal-Palenque Highway is from those who stand to lose some of their land to the current highway’s expansion. There is resistance from indigenous peoples and environmentalists because the highway is the backbone for an economic development zone; specifically, an upscale tourist zone that would remake the approximately 35-mile corridor between the Agua Azul Cascades and the Palenque archaeological site into a world-class resort for elite tourism.

The plan for accomplishing this makeover of an entire Chiapas micro-region is the Palenque-Agua Azul Planned Integral Center (PPIC, its initials in Spanish). What is known about this plan is that the government intends to construct a 5-star European hotel, a Conference Center with golf course and a Lodge with helipad overlooking the waterfall at Bolom Ajaw, a Zapatista community on land reclaimed in 1994. The PPIC envisions that these upscale facilities will require a lot more electricity, so there are plans to build dams on 3 of the rivers in this region.Without an improved highway, the PPIC is not likely to become a reality.

The Palenque site is an archaeological wonder left to us by ancestors of the modern-day Maya who inhabit this part of the state. The Agua Azul Cascades are a series of turquoise waterfalls that cascade down a mountain surrounded by lush green jungle. A number of large ejidos (collective farms), many of them containing communities of Zapatistas and their supporters, are located within that 35-mile corridor. Many could face displacement and the loss of their food security. Thus, they protest and face the violence of State repression and/or violent attacks from pro-government groups. Several recent incidents are described below.

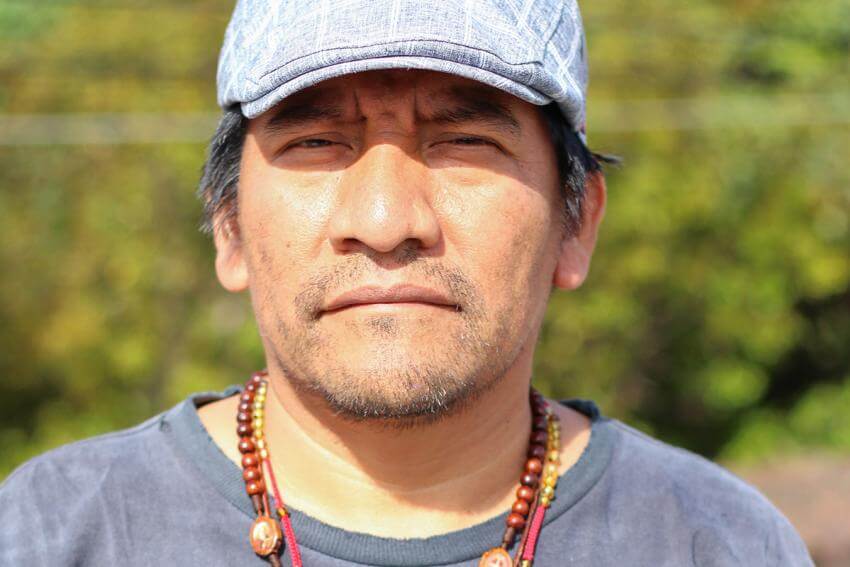

The statement from the Diocese of San Cristóbal specifically mentions the arrest of its Pastoral Agents, among them Manuel Sántiz Cruz, first arrested by the National Guard without a warrant on May 30, 2022, released the next cay and immediately re-arrested with a warrant by state police and charged with murdering a local police agent. Sántiz Cruz is an indigenous Tseltal defender of human rights and territory in the San Juan Cancuc parish, as are the other four members of the same parish arrested and imprisoned with him. At the time of his arrest, Sántiz Cruz was president of the San Juan Cancuc Human Rights Committee, which opposes both the National Guard’s presence and expanding the Highway of the Cultures.

A forced displacement of civilian Zapatista families took place on July 14, 2022 in El Esfuerzo, Comandanta Ramona autonomous municipality, official municipality of Chilón, due to a violent attack by members of the Muculum Bachajón Ejido. Few other facts are available, but Chilón is one of the municipalities in which the Highway of the Cultures will be expanded; it’s close to the Agua Azul Cascades. Banners in El Esfuerzo community express opposition to the megaprojects.

New highways or expanded ones are built to bring economic development. The Highway of the Cultures and the Transversal Highway are seen as part of capitalism’s effort to drag the indigenous peoples of Chiapas into its global economic system, as well as an effort by politicians and business interests (both legal and illegal) to dominate the region.

Municipal Electoral Violence

There has always been some electoral violence between political parties in Chiapas. That’s not a new phenomenon. Now, electoral violence, like counterinsurgency, seems to be on steroids. The presence of competing national organized crime groups and the money from crime has perhaps increased what’s at stake and also the intensity of the violence. The most recent electoral cycle in June 2021 generated violence in a number of Chiapas municipalities.

There are two municipalities where electoral violence broke out as a result of the June 2021 municipal elections and there has been enough media coverage to make a comparison: Pantelhó and Altamirano. Both municipalities experienced violence in their efforts to overthrow anti-democratic municipal governments allegedly linked to organized crime.

A self-defense group (autodefensas) calling itself El Machete emerged in Pantelhó and forced out the municipal president and his municipal council. El Machete also removed a group of alleged sicarios (hit men) from their homes and forcibly took them away from the municipal seat. El Machete alleged that the sicarios were responsible for the murder of 200 people in Pantelhó and were responsible for the. murder of Simón Pedro Pérez López, a catechist and past president of Las Abejas. It was the murder of Pérez López on July 5 2021, that motivated the population to rise up and throw out the municipal president and the council. El Machete further alleged that the sicarios worked for a local organized crime group headed by the municipal president. As of this writing, 19 of the alleged sicarios have not been heard from since they were kidnapped on July 27, 2021.

Soon after residents of Pantelhó threw out the municipal president, they proceeded to elect a new municipal government through their own traditional method of electing municipal authorities, which does not rely on political parties or official government procedures, but is acceptable to the population. It took the State Congress five months to accept and approve those authorities! And now two of them, Pedro Cortés López and Diego Mendoza Cruz, have been arbitrarily arrested and the State Congress has appointed an entirely new municipal council.

Meanwhile, residents of Altamirano municipality were faced with a situation that shared some similarities to that of Pantelhó. Altamirano’s municipal president-elect, Gabriela Roque Tipacanú, was the wife of the outgoing municipal president, Roberto Pinto Kanter, a member of the cacique family that had dominated the municipality for years and was alleged to work with a local organized crime group referred to by its initials as the ASSI. Roque Tipacanú was supposed to taken office on October 1, 2021. However, a day or so before October 1, her opponents, members of the Altamirano ejido, apprehended her husband, placed him in the ejido jail and said they would not release him until she resigned. The municipal president-elect resigned, as did the entire municipal council. They released Pinto Kanter, and Altamirano residents selected people to replace the former authorities and asked the State Congress to approve them.

The State Congress approved a new Altamirano municipal president (mayor) and other members of the municipal council one month after the municipal president-elect resigned. After that approval, ASSI members who supported Pinto Kanter and his wife responded by kidnapping 54 people to use as leverage with the State Congress to remove the municipal council it had just approved. The kidnappers, alleged to have ties to organized crime, also burned vehicles and houses, as well as killing a cousin of the new municipal president and wounding a young girl in a shooting incident at one of their roadblocks. Despite these efforts of the opposition, State officials did not remove the new council. Many of the hostages were held in captivity for five months, but the State eventually was able to negotiate their release and the new municipal council remains in power.

A self-defense group also emerged in Altamirano. It did not disclose its name “out of respect for our Zapatista brothers.” No reports have been published about this group of autodefensas having engaged in violence, but the group issued videos with a political analysis. In one of the videos the self-defense group made it clear that it would not accept a non-indigenous person as municipal president. The new municipal president is María García López, an indigenous woman from the Tseltal zone of the municipality.

Migration

Chiapas is the state where many migrant peoples enter Mexico on their way to the United States (US). The US pays Mexico to arrest and turn back migrants who cross the Chiapas/Guatemala border illegally. Mexico’s Army and National Guard patrol in large numbers. For those migrants who choose to travel through Mexico legally, there are big backlogs in Chiapas, especially in the city of Tapachula, an entry point for many migrants. Tapachula is often like a holding cell, full of desperate migrants who await permits to travel through Mexico legally. There are also militarized checkpoints throughout the routes that migrants usually travel. News reports say that migration attracts organized crime. NBC News and Telemundo published a report on the cartels that prey on defenseless migrants near Mexico’s northern border. Organized crime cartels also prey on migrants in Chiapas, Mexico’s southern border. Smuggling migrants across and between borders is now a profitable business and drug cartels have diversified their business plan to exploit migrants and reap those profits.

Migration is a huge issue of its own taking place in Chiapas apart from those of us involved in reporting on the Zapatista movement for indigenous rights and autonomy. Migration draws both organized crime and law enforcement forces to the state. Once in Chiapas, organized crime groups are involved in other criminal activity involving violence, such as the activities described by the Diocese in its statement. In addition to repressing migrants, law enforcement becomes involved in other violent repression. In the case of the National Guard, it is involved in containing migrants, but also in containing the state’s civilian population protesting extractive activities like mining, or against mega-infrastructure projects, such as highways or dams. Such repression causes defenders of human rights and territory to speak of the criminalization of social protest. Likewise, migration is criminalized. The violence of both organized crime and law enforcement against migrants adds to the violence taking place in the state around megaprojects, electoral power struggles, drug trafficking and “low-intensity war” against the Zapatistas.

Increased militarization

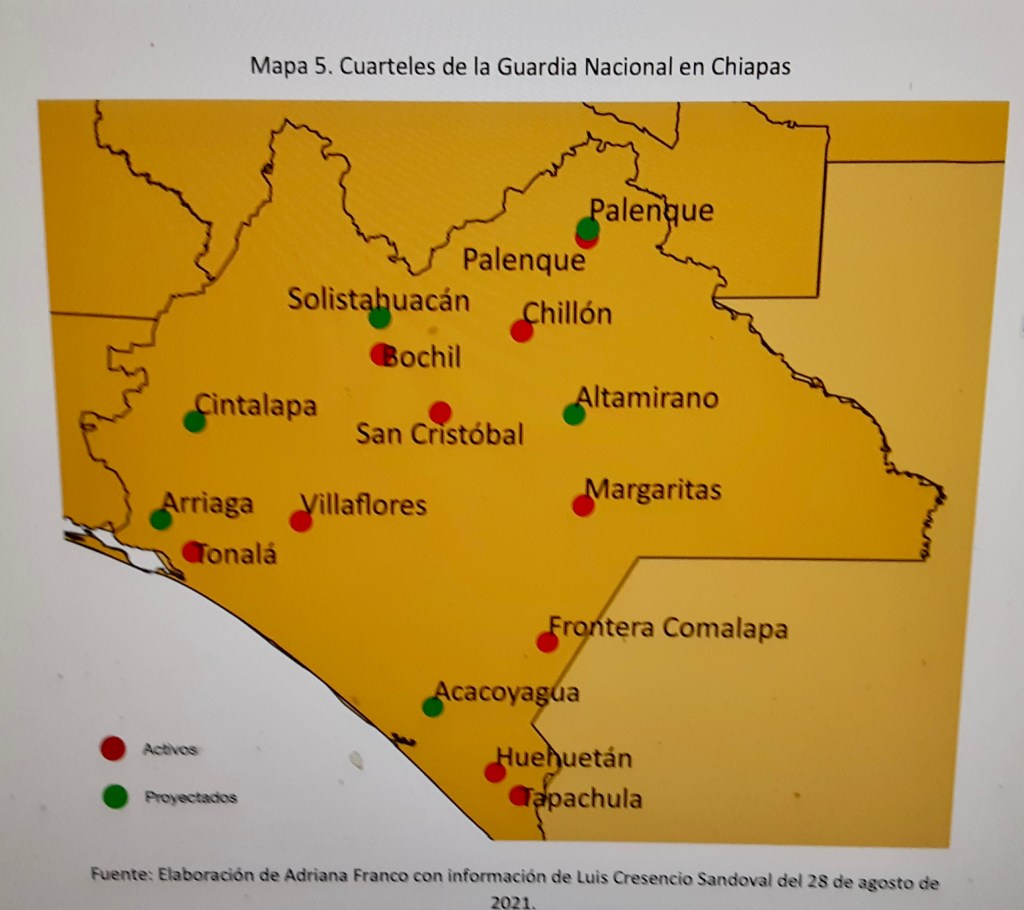

AMLO created the National Guard and distributed them throughout the country. This has led to the construction and/or planned construction of National Guard barracks in Chiapas and increased militarization of the state, which was already heavily militarized. A majority of the barracks are near routes used by migrants and organized crime. Some camps are located in areas that are heavily Zapatista.

According to a research paper entitled “Militarization of the Mexican Southeast” and compiled by the Latin American Observatory of Geopolitics, as of August 28, 2021, Mexico’s National Defense Ministry (Sedena, its Spanish acronym) reported that 10 National Guard barracks had been built in Chiapas and are located in the following municipalities: Villaflores, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Tonalá, Huehuetán, Tapachula, Chilón, Las Margaritas, Frontera Comalapa, Bochil and Palenque. It also reported that there were plans to build 6 more barracks in the municipalities of Cintalapa, Arriaga, Acacoyagua, Altamirano, Palenque and Solistahuacán. More recent sources report that 6-8 additional barracks are planned, including one for Ocosingo and a second barracks in Las Margaritas.

There has been repression around the protests over construction/installation of National Guard barracks in Chilón municipality near San Sebastián Bachajón and recently around protests in San Juan Cancuc over expansion of the Highway of the Cultures. Those protesting are indigenous Zapatista sympathizers and supporters organized in large movements like MODEVITE and Pueblo Creyente. Additionally, some protesters are CNI-CIG (National Indigenous Congress-Indigenous Governing Council) and are adherents to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration. An example of such repression is described below.

On October 15, 2020, the Maya Tseltal people of Chilón peacefully demonstrated against the construction of the National Guard barracks in their territory, located in the Northern Zone of Chiapas. In the morning, around 300 members of the municipal police, State Police and National Guard repressed the protest at the Temo crossroads on the Ocosingo-Palenque Highway. Two community defenders, César Hernández Feliciano and José Luis Gutiérrez Hernández were arbitrarily arrested, tortured and then indicted on charges of rioting. Eleven other people were injured during the repression. César and José Luis were released “under caution” on November 1, 2020, with the requirement to sign in at the control court every 15 days while awaiting trial. The judge limited their ability to travel to the municipalities of Chilón and Ocosingo.

There are concerns about National Guard barracks being located near Zapatista caracoles (centers of government and resistance). For example, Bochil is located in the Highlands, not far from Oventic (Caracol 2), Las Margaritas is close to La Realidad (Caracol 1) and Altamirano is the municipality in which Morelia (Caracol 4) is located. The National Guard has multiple responsibilities, one of which is to assure tourists that Chiapas is a safe place to visit. Therefore, the location of its barracks can serve multiple purposes. An example of this would be Palenque, which is already a big tourist area and will be even bigger when the Maya Train is up and running. Roberto Barrios (Zapatista Caracol 5) is not far from the city of Palenque and the archaeological site of the same name, so a National Guard barracks in Palenque can serve the dual functions of tourist safety and monitoring/repressing the activities of the Zapatistas and their supporters in a region the government wants to develop into an upscale tourist resort.

The remaining National Guard barracks seem to be concentrated on routes used by both migrants and and organized crime.

Since 1994, the Mexican Army has had numerous large military headquarters, bases and small camps strategically placed throughout Zapatista Territory. Since the United States discovered Mexico’s long and “porous” border with Guatemala, militarization of the border zone has skyrocketed.

In Chiapas, the increase in military personnel is not only to assist the Army with organized crime battles and to back up the Army in containing migrants; it is also there to protect the government’s infrastructure projects., which means it is there to repress those who oppose the projects.

Summary and Conclusion

Violence can play an important role in economic development projects. Violence is perpetrated by criminal groups, some of them paramilitary-style groups, others who traffic drugs and humans. But those groups require governmental support in the form of impunity in order to function. Impunity means that the government’s forces of law and order, including the courts, stand idly by and fail to deter or punish those committing crimes that inflict violence on the civilian population. The result of such impunity is that organized crime thrives and the population suffers displacement, dispossession of land, murder, and other physical and psychological violence. Consequently, the population lives in fear.

Added to unpunished organized crime violence is the repression from paramilitary groups, the Army, National Guard and various police forces against those who protest. The sum total of all this violence is intended to leave the population weakened and afraid, and thus clearing the way for the infrastructure projects deemed necessary for economic development. Violence and repression create fear in the population, the fear of worse violence and repression if they organize and mount a strong opposition.

The World Bank and its Latin American branch, the Inter-American Development Bank, see fertile land, sweet water, a wealth of natural resources and beauty, cheap labor and archaeological wonders in Chiapas and believe that lots of money can be made by exploiting them. They also believe that they have the right to exploit them. So, they back the financing of infrastructure projects, even when a large segment of the population objects. This is what some analysts of the economic system call accumulation by dispossession and the Zapatistas call the “Fourth World War.”

The Zapatistas and their supporters and sympathizers face a difficult situation, possibly the most complex and difficult threat they have faced in recent years. It would seem to follow that those of us in solidarity with the Zapatista movement ought to be stepping up our solidarity work in response.

Published by the Chiapas Support Committee, an adherent to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, and a 501c.3 nonprofit in Oakland, California.

Armed group in Chenalhó keeps a community under siege, and murders several residents

By: Ángeles Mariscal

Since Thursday, September 29, an armed group of approximately 60 people in Santa Martha, Chenalhó, has kept the Atzamiló community, located within the same ejido, under siege; it killed at least four people, denounced residents.

The events occurred because at the beginning of this year, in Santa Martha, the population decided to sign a peace and disarmament agreement, which led them to expel from Santa Martha those who make up an armed group that keeps the population of the neighboring municipality of Aldama under siege.

According to the version of Santa Martha residents, this group lowered the level of attacks on Aldama, but keep those who expelled them under threat, and attempt to recover several houses and lands with the use of force.

In this context, last Thursday, September 29, around 10 in the morning, they arrived in the lands of the Atzamiló community to seize cultivation areas. Given the facts, the Ejido Commissioner of Santa Martha, Jesús Jiménez Velasco, went to the place where the armed group attacked, without being injured.

They also shot at the population, burning houses and land with crops on it. Relatives of an elderly man named Juan Antonio Pérez reported that he and another young man died as a result of the shooting. They also explained that Juan Antonio’s wife had to flee with her grandchildren to the nearby mountains.

Interviewed via telephone, the Ejido Commissioner, Jesús Jiménez Velasco, said that he fled from the area after the attack given the risk that they would assassinate him: “I left my community because of fear,” he explained. Even before fleeing, the Commissioner had reported the death of a campesino and two more injured by firearms.

Hours later, around eight o’clock at night, neighbors of Atzamiló reported that a state government helicopter flew over the area and was also hit by shots from this community, where the armed group was located.

On Friday afternoon, after a day of being under siege, inhabitants of Atzamiló managed to communicate to denounce that some of them are hidden in the mountains, because the armed group -they say about 60 people- has control of the community and the accesses to the area and to Santa Martha, located several kilometers ahead. They also denounced that there are four people dead and several injured.

They explained that the access roads to that area are blocked by their aggressors, and that authorities of the Chiapas government and the National Guard have not been able to enter area.

“This group wants to continue attacking; they are the ones who attack Aldama. They want to continue the violence; we said no more and that’s why they are attacking us now. We ask that the police arrive because there are people injured and killed by the shots,” explained one of the residents of Santa Martha, who managed to reach the city of San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

The State’s Attorney General (FGE) reported that he opened an investigation notebook for the homicide of Alfredo “N”, “after the events that occurred in the Santa Martha sector, Chenalhó municipality, on the afternoon of Thursday, September 29 of this year.” The agency has not reported on the attacks after the first homicide.

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Friday, September 30, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/noticias/chiapas/2022/09/grupo-armado-de-chenalho-sitia-comunidad-asesina-a-varios-pobladores/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Mexico III. Father Marcelo: “The earth groans the pains of childbirth”

Raúl Zibechi interviews Father Marcelo

By: Raúl Zibechi

“We are living something similar to the times of Jesus. The Romans had no mercy. The narco has no mercy,” says Father Marcelo Pérez, sitting in the dining room of the parish of Our Lady of Guadalupe, in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas.

The church rises atop a mound that is reached snorting down the 79 steps uphill. The reward is a great panoramic view of wooded mountains above the white colonial city. In between, as if articulating the natural mantle and the urban stones, the church is surrounded by a landscaped square where we find Father Marcelo, always surrounded by people who consult him and ask him for advice.

Marcelo was educated in the Diocese of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, which he defines as “very conservative,” but was sent to Chenalhó in 2001, where his life took a turn. “Acteal gave me light,” he says with firmness. The Acteal Massacre, on December 22, 1997, which left 45 Tsotsils murdered while they were praying at the hands of paramilitaries formed to fight the EZLN, continue having a brutal presence in the municipality and in all Chiapas.

“I was afraid but I could see that in Acteal the people are free. I am a pastor but the sheep are very brave. I joined with them to denounce the impunity and to struggle against the Rural Cities project of the Juan Sabines government,” the father continues, in a story that takes him from the years of formation to the commitment to his people.

He rejects being inspired by Liberation Theology and he recites the four pillars of his thinking and way of doing: the reality that we confront; the word of God before it; the position of the Church; and the commitments that must be assumed. “Talking about Liberation Theology is inserting yourself into conflicts,” he assures pragmatically.

Then he returns to his theme: “Acteal converted me.” The pain that is born when he listens to the survivors, to María, to Zenaida, to women and men who lost their whole family. “How to tell them that God loves them,” the priest exclaims. That’s why the biblical word doesn’t inspire him, or in the theory that is born from sacred text, rather he takes another direction, “to cry with those who cry, to suffer with those who suffer” and, especially, “to walk with them.”

The path is not a change of parties

The words roll over the table with a simple lunch. We are enveloped by his enthusiasm and the sincerity of his pain. “Survivors know how to read, there’s the light.” It is impossible not to forget very similar words spoken decades ago by the murdered Monsignor Oscar Romero, who expressed himself in a very similar way to Chenalhó’s father: “The blood of Rutilio Grande converted me,” he said in reference to the martyr of the Salvadoran peasant movement.

The conversion of Father Marcelo led him to walk with the campesino people. Not only did he accompany the victims but he also denounced the material and intellectual authors of the violence, which caused persecution on the part of the Chiapas government. “In 2008, they set fire to the parish house, then damaged the spark plugs and tires of my car, and on December 12, 2010, two young men beat me up in the street,” he says calmly.

He was close to death when they connected a cable to the vehicle’s gasoline tank, which made him accept his transfer to Simojovel, where he arrived on August 5, 2011. “People started coming to tell their pains, the deaths. There I discovered that the criminals have agreements with the authorities and complaints provoked threats.”

On March 8, he organized a women’s march against the sale of drugs that was done at the side of the municipal presidency. They accused him of being a guerrilla and even a Zapatista, they put a price on his life until in 2014 the municipality and the PRI attempted to mobilize the population against him, with very little popular following.

An inflection point was the pilgrimage of 15,000 people in October denouncing the Gómez Domínguez family, who entered on the scene through sicarios who carried out attempts and a media campaign against Father Marcelo, which led them to offer one million pesos for the head of the parish priest of Simojovel (https://bit.ly/3DIAWbp).

In the cited communication, Pueblo Creyente (Believing People, or People of Faith) conclude that change doesn’t come from a party “but rather from civil society, Native peoples, the poor and the middle class,” and it denounces that Chiapas “is approaching a social explosion.”

Pueblo Creyente’s form of action is to convoke marches/processions, which tens of thousands of people of faith attend, as well as denouncing authorities and politicians. It achieved that the Gómez Domínguez brothers didn’t win the municipal elections but it resulted in a defamation complaint to the PGR [2], although he recognizes that “the path is not changing parties.”

In the years that followed there were sit-ins of the population and assassinations of organized crime, always protected by the authorities. “On December 12, 2017, I had the saddest Mass of my life, for the death by cold and hunger of two elderly people.” The forced displacement of entire communities continues, more violence and deaths, bombs and shootings. But the population continued to resist.

In May 2017, the Indigenous Movement of Zoque People of Faith in Defense of Life and Territory (ZODEVITE, its Spanish acronym) was created and in June it held a mass march/procession to Tuxtla Gutiérrez against concessions for mining and hydrocarbons, since the Mexican government sought to give concessions to foreign companies for more than 80,000 hectares affecting more than 40 ejidos and communities.

The mobilization was a new defeat of the plans of above, but the violence continues. During 2021, more than 200 deaths crime were committed in Pantelhó by organized crime, in a municipality of just 8.600 inhabitants in the Chiapas Highlands.

On July 3, Mario Santiz López was murdered. On July 5, 2021, they murdered Simón Pedro Pérez López, a catechist and former president of the board of directors of Civil Society Las Abejas of Acteal, who promoted non-violence. He was murdered for the crime of accompanying the Tsotsil communities of Pantellhó. At the wake Marcelo accused the “narco-municipal council,” in other words, the alliance between the State and organized crime.

Although he asked the communities “not to fall into the temptation of revenge,” on July 10 a statement came out from the armed group “El Machete” created by the communities as self-defense in the face of violence. On July 26, 2021, thousands of hooded people took the municipal seat, 19 men were shown in the central square with their hands handcuffed for having links to organized crime.

Although it was a collective community action (an outburst from below), which apparently was not called by El Machete, the Chiapas Attorney General’s Office issued an arrest warrant against Father Marcelo for the disappearance of 19 people in Pantelhó. They did not care that the priest was in another place that day, in Simojovel, that he always called for peace and that he arrived the day afterwards to calm the spirits.

It’s the life of the people, not mine

The arrest warrant remains in force. In October [2021] he was transferred to the church of Guadalupe, where he now explains who is provoking violence and death. “The authorities are accomplices of the narco. They have sought a way to silence us, through death threats and defamation on social networks. You feel scared, but that doesn’t stop me. “

In his analysis of the situation, this indigenous Tsotsil who has been a priest for 20 yeas in Chiapas maintains that it’s not possible to stop the violence because the police are sicarios (hit men), because “we have a narco-State.” He is convinced that the violence is going to get worse and that later a certain calm will come, but at the cost of a lot of blood. “May it be the blood of priests and bishops, and not of the people.”

He maintains that we are in the middle of the storm, which is not solved with more storm but by looking for other paths. He distrusts the powers and the powerful: “If they kill me, it’s a scandal; but if they kill a peasant nothing happens. If it helps to give my life, here I am,” he concludes.

Before saying goodbye, he appeals to a biblical phrase, assuring that the pains we go through are “the groans of childbirth”. He puts his principles and values ahead of his own life: “I don’t accept bodyguards. It’s against the Gospel for someone to die in order for me to live. It is not my life but that of the people.” At the end of the final greeting, he confesses: “I don’t trust the police.”

Originally Published in Spanish by Desinformemonos, Monday, September 26, 2022, https://desinformemonos.org/mexico-iii-padre-marcelo-la-tierra-gime-dolores-de-parto/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Ayotzinapa, the Time Tunnel

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

It seems like a trip through the Time Tunnel, back to the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto. The EjércitoMX.Noticias tweet reports: Here I leave you the interview with General José Rodrígues Pérez, investigated for the Ayotzinapa case. In front of the camera, in the facilities of Military Camp No. 1, as if he were not in prison, the Brigadier appears, talking with journalist Jorge Fernández Menéndez for a radio program (https://bit.ly/3BO0Qrw).

Jorge Fernández, the military interviewer, is one of the most unconditional propagandists of “the historical truth.” The regimes of the PRI and the PAN made use of his pen to justify the most heinous crimes and filter their versions of the worst atrocities, Ayotzinapa included. His fake documentary, La noche de Iguala (The night of Iguala) is publicity garbage, not only to cover up what happened in Guerrero eight years ago, but also to criminalize the rural teachers’ colleges (normales, in Spanish). His cinematic pamphlet exudes the unmistakable stench of the pipes of power. It is the direct heir of ¡El Móndrigo!,cooked up in the basements of the intelligence services to discredit the student movement of 1968. (https://bit.ly/3LG3d4p).

September 26th and 27th of 2014, now-retired General Rodríguez Pérez held the rank of colonel and led the 27th Infantry Battalion in Iguala, with a long history of counterinsurgency. According to the undersecretary of the Interior, Alejandro Encinas, he had given, among other orders, the one to murder and disappear six students from Ayotzinapa, who were being held alive in a warehouse, four days after the attack on the normalistas (teachers college students).

The general was not arrested. He turned himself in voluntarily (“presented” himself, he says) on September 21st. He is accused of organized crime, not homicide or forced disappearance. In one of the tweets disseminating the interview, @Sedenanoticias warns: Don’t be fooled, the military did not intervene in the disappearance of the normalistas, as Alejandro Encinas wants to make us believe (original typos respected here.) The military man lashes out against the undersecretary: “what they did was vile. It was cowardly, to have spoken outside of the law,” the person states.

The institution is supporting me, the general explains. It’s true. Sedena [1] went all out to protect the ex-commander. It not only allowed the journalist into Military Camp 1 to interview him, eliciting his answers, but also, broadcast excerpts of the program. In addition, along with the military public defender’s office, he added heavyweight lawyers, Alejandro Robledo y César González Hernández, pro bono to his defense, who have just come out of loud legal disputes with the prosecutor Alejandro Gertz Manero.

On August 18th, the undersecretary announced arrest warrants against 20 soldiers related to the night of Iguala. However, so far, only three more have been arrested, in addition to General Rodríguez. Second Lieutenant Fabián Alejandro Pirita Ochoa and the Infantry soldier Eduardo Mota Esquivel. The other, Captain Jose Martinez Crespo, was already in custody and was served with a second arrest warrant.

The Armed Forces’ defense of General Rodríguez and the rest of the military personnel implicated in the forced disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students and in the invention of the “historical truth” is an indicator of its refusal to get to the bottom of the events of the night in Iguala. Their refusal to share the information that they have about what happened, and their refusal to respond to the requests for documentation to clarify the crime against humanity creates tremendous skepticism about the future of the investigation.

This, despite the fact that the report of the Commission for Truth and Access to Justice points out how the military from the 27th Infantry Battalion of Iguala not only did nothing to prevent it and falsified what happened, but also murdered and disappeared some of the 43 youths (https://bit.ly/3C7GIlw).

The report, an investigation made by Encinas, with the powers given to him by decree, has already been submitted to the Special Prosecutor’s Office for the Ayotzinapa Case. The latter should be the one to follow-up, prosecute the investigation and bring the subsequent criminal proceedings.

However, this has not been the case. It was the Attorney General for the Republic and NOT the Special Prosecutor’s Office for the Ayotzinapa Case, that issued the accusation against Murillo Karam. Additionally, inexplicably, it reversed course, to cancel 21 arrest warrants, 16 for organized crime and forced disappearance, which had already been issued for military commanders, and members of the 27th and 41st Infantry Battalions.

In what would seem another return to the past, Vidulfo Rosales, lawyer for the Ayotzinapa families, is being subjected to an insulting campaign of attacks very similar to that which he experienced in the time of Peña Nieto. (https://bit.ly/3fqk1QU y https://bit.ly/3RnFKGs) All for defending the victims and seeking to explain the behavior of the outraged rural normalistas prior to trying them.

According to him, the armed forces are hermetic, closed, and unwilling to contribute to the clarification of this case. They are reluctant to go to the courts. They are not inclined to have mechanisms of judicial control over them. To go to the judges, to give an account of whether they participated or not. There is no such thing. This is our concern. If the armed forces are in this position, it is going to be very difficult for us to come to know the truth(https://bit.ly/3BN8HWr). If this hypothesis is confirmed, the trip to the Time Tunnel will be more than a metaphor.

[1] Sedena is the acronym for the Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional, Mexico’s Defense Department.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, September 27, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/09/27/opinion/014a2pol/ Translation by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee