Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Transnationals covet resources in Zapatista territory: SEDENA

Las Margaritas, Chiapas, October 14, 2017 – Autonomous Zapatista authorities receive María de Jesús Patricio Martínez “Marichuy,” in the community of Guadalupe Tepeyac. Photo: ADOLFO VLADIMIR / CUARTOSCURO.COM

By: Zosísimo Camacho

Minerals, water, wood and fossil fuels are among the resources identified by the SEDENA in Zapatista Territory. They are of interest to transnationals such as FEMSA Coca Cola, Frontier Development Group and First Majestic, and to the public companies CFE and Pemex.

The “complaints” of the “self-named” Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) to the Mexican State are focused on the current “mining, oil wells, super highways, highways and mega [water] wells” concessions, as well as on the construction of the Maya Train, according to an internal document of the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA), dated February 2020.

It warned that the policies and development projects of the federal government in the indigenous regions, as well as the continuity of the concessions granted in previous six-year periods, have “increased the tension” between the Zapatista bases and leaders and those of the federal government.

The study Socio-political Activism of the EZLN and its Impact on the National Security, ordered by SEDENA to its Mexican Institute of Strategic Studies in Security and National Defense, pointed out tensions between the Zapatista movement and the federal and state governments due to the arrival of public and private companies to indigenous territories throughout the country. And, particularly, the intentions to explore the Chiapas territory of Zapatista “influence.”

It cited the cases of the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE), Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), FEMSA Coca Cola, Frontier Development Group, First Majestic Silver Corp, Radius Gold and Blackfire Exploration.

It emphasized that at the heart of the complaints was the extraction necessary for development projects, from water, gas and oil, to timber and precious and industrial minerals.

The report placed the EZLN as one of the poles around which part of the leftist opposition to the 4T is articulated. The issues underpinning the discourse of this opposition are indigenous rights, water management, mining exploitation, electric power generation projects and the Maya Train (Tren Maya).

In the document “El Activismo Sociopolítico del EZLN” (The Sociopolitical Activism of the EZLN) — elaborated in February 2022– SEDENA identified what until then were, in its opinion, the main disputes between the Zapatista movement and the government of the so-called Fourth Transformation.

Classified as “confidential,” the report pointed out that the EZLN “has become the main reference point for the indigenous community rights complainants in the country.” It considered that this had been possible because Chiapas is inhabited by 1,800,000 indigenous people. Eight out of 10 live in extreme poverty, “most of the times due to their own ancestral usos y costumbres (customs and traditions), with traditional difficulties in incorporating themselves into national development,” according to Sedena’s vision.

It also stated that, while “AMLO” (Andrés Manuel López Obrador) was in the opposition, Obradorismo and Zapatismo were “independent allies.” They had no formal relationship or association, but agreed at various junctures. Such a situation ended in 2017, when the relationship between the bases of Zapatismo and those of the National Regeneration Movement (Morena) became tense.

With the electoral triumph of Obradorismo, the relationship became even more tense. According to SEDENA’s assessment, Lopez Obrador “sent direct messages to indigenous groups with the intention of diluting any hostility and confrontation. At the inauguration, the second ceremony, held in the Mexico City Zócalo after the official one in the Chamber of Deputies, there was an indigenous ceremony linked to the presidential investiture and the leadership of the indigenous groups. Various indigenous groups participated, the EZLN was not present” (sic).

The analysis acknowledged that Zapatismo is a referent for social struggle in the world. Since its irruption in 1994 “various models of social participation have been strengthened in different parts of the world.” It mentions the Sao Paulo Forum and the Podemos party of Spain among the expressions of “critical anti-globalism” that have Zapatista inspiration.

It stated that after the “containment” of the armed uprising, the EZLN focused its activism towards the demand “to generate in Mexico a multinational system within the State in the framework of human liberties, which would seek the modification of the current constitutional structure.” It referred to the demand for respect for indigenous rights and culture, embodied in the San Andres Accords which, to date, have not been recognized by the Mexican State and whose central demand is autonomy for the native peoples, tribes and nations.

The document pointed out that López Obrador’s style of governing and exercising his leadership had contributed to the break with Zapatismo. The president has sought a direct relationship with indigenous groups and individuals, “undermining the leadership. This eliminated a possible “communication and good coordination with the EZLN,” according to SEDENA.

Obrador’s term has not reduced the Zapatista base, the study pointed out. As of February 2020, the EZLN had managed to keep its communities loyal and had even expanded “its territory of influence.”

It recalls that at the time the proposal of the original Maya Train project –whose route was intended to cross Zapatista territory– would generate “confrontation on various fronts with the EZLN, including the armed one,” since the guerrilla had “said that they would defend even with their lives” their territorial integrity.

The rekindling of the conflict in the southeast could have been unleashed after the “supposed approval of Mother Earth [to the Maya Train project] in a limited and controlled referendum,” it warned.

Water, mines and other resources

Other points of conflict between the 4T and the Zapatista movement were “[…] the complaints about water [that] are linked to hydroelectric plants such as Malpaso, La Angostura and Chicoasén, which supply other states of the Federation and generate electricity for the national system, which is also sold to Guatemala; this issue nourishes the social problem of water as part of the Zapatista discourse […].

The analysis warned that this situation is taken advantage of by the EZLN, since “[…] the Zapatista rhetoric is based on [questioning] who is the true owner of water as a national security issue […]”, an issue on which they coincide with populations from all over the country.

To the dams already in operation others will be built during the current government: Peñitas and Itzantun, which are priority projects because they will allow Chiapas to generate “approximately 50 percent of the national electric energy; in contrast, the data indicate that 47 percent of the inhabitants of the state […] lack electricity supply.”

It also pointed out that Zapatismo was repositioning itself among the indigenous communities of the Republic by questioning mining activities. This industry has plans to execute large projects in Chiapas, as it already does in other states of the Republic.

“In the last federal administration, nearly 99 mining concessions were granted for 50 years, along with 54 mining projects for the state [of Chiapas], where Canadian and Chinese mining companies are fundamental, requiring cheap labor and large quantities of water for their own extractive activities, right in a region that is having problems with water supply […]. The state of Chiapas, besides being one of the main water reserves, has 13 types of basic minerals for global development such as: gold, silver, copper, zinc, iron, lead, titanium, barite, tungsten, magnetite, molybdenum and salt.”

These resources are located in “regions compromised by the influence of the EZLN.” In this regard, the document cited the constitutional municipalities of Acacoyagua, Acapetahua, Chicomuselo, Frontera Comalapa, Tapachula, Tonalá, Ángel Albino Corzo, Escuintla, Motozintla, Ixhuatán, Mapastepec, Pijijiapan, Siltepec and Solusuchiapa Contalapa.

It also listed the companies that have concessions granted by previous governments and that are interested in undertaking extraction projects. They are: one of Chinese origin, Up Trading, and five Canadian companies: Frontier Development Group; First Majestic; Silver Corp; Radius Gold, Inc, and Blackfire Exploration, Ltd.

These companies were granted concessions in Chiapas for “the largest barite mine in the world, an essential material for oil drilling, from which 360 thousand tons are obtained annually, in addition to the titanium and magnetite concessions in the municipalities of Pijijiapan, Acacoyagua and Chicomuselo.”

It added that the entire Soconusco region is of interest to foreign corporations dedicated to the extraction of uranium and titanium. The former, “used in the processing of energy in nuclear plants”; the latter, “in the manufacture of airplanes, helicopters, armor, warships, spacecraft and missiles.” For this reason, both are coveted by “today’s military powers such as the United States, China and Russia.”

It pointed out that in terms of mining, Chiapas is divided into seven districts. In addition to the listed minerals, amber, limestone, quartz, zhanghengite, clay, sand and sulfur are extracted in these districts.

The interests in the extraction of these resources “coincide” with the plans for a highway route with private investment from Pijijiapan, in the Soconusco area, to Palenque. Added to this is the Maya Train “and its cargo mobility along the Peninsula located between the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.”

In terms of oil, Pemex works in 24 Chiapas areas located in five municipalities: Reforma, Juarez, Pichucalco, Ostuacan and Sunapa. It operates 129 oil, oil and gas wells. “Likewise, Chiapas has one of the largest gas processing complexes in the southeast of Mexico: Cactus. It occupies an expanse of 1,822 kilometers.

The analysis pointed out that the social programs Sembrando Vida, Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro and the Benito Juárez scholarships are linked to priority projects such as the Maya Train and National Reforestation. “They have a great impact due to the current conditions of poverty and social inequality, even more so with the numbers in the indigenous population.”

The document –part of the thousands of files hacked from the SEDENA by the Guacamaya group of cyber hackers– also issued “recommendations” to the federal government with respect to Zapatismo. The first of them stated: “the President of the Republic should consider in his discourse the provocation towards the EZLN, avoid open confrontation that favors the formation of an indigenous front against the government and the Armed Forces.”

It also pointed out that: “the intelligence attention to Zapatista women is not clear and exact; it’s relevant to monitor and follow up on them, given that they are often the carriers of messages from the EZLN leadership to other organizations.”

It concluded that “the social activism of the EZLN and its adherent communities has not reached the level of a threat to the National Security of the country; the social, economic and political backwardness of the Chiapas area requires the attention of all levels of government, from federal to municipal, in a coordinated effort, including consideration of the problems of the EZLN itself.”

Originally Published in Spanish by Contralinea, Sunday, December 18, 2022, https://contralinea.com.mx/interno/semana/trasnacionales-codician-recursos-naturales-en-territorios-zapatistas-sedena/ with Translation by Schools for Chiapas and Re-Published by the Chiapas Support Committee

Memory of the Machetes of War

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

Photos: Mario Olarte

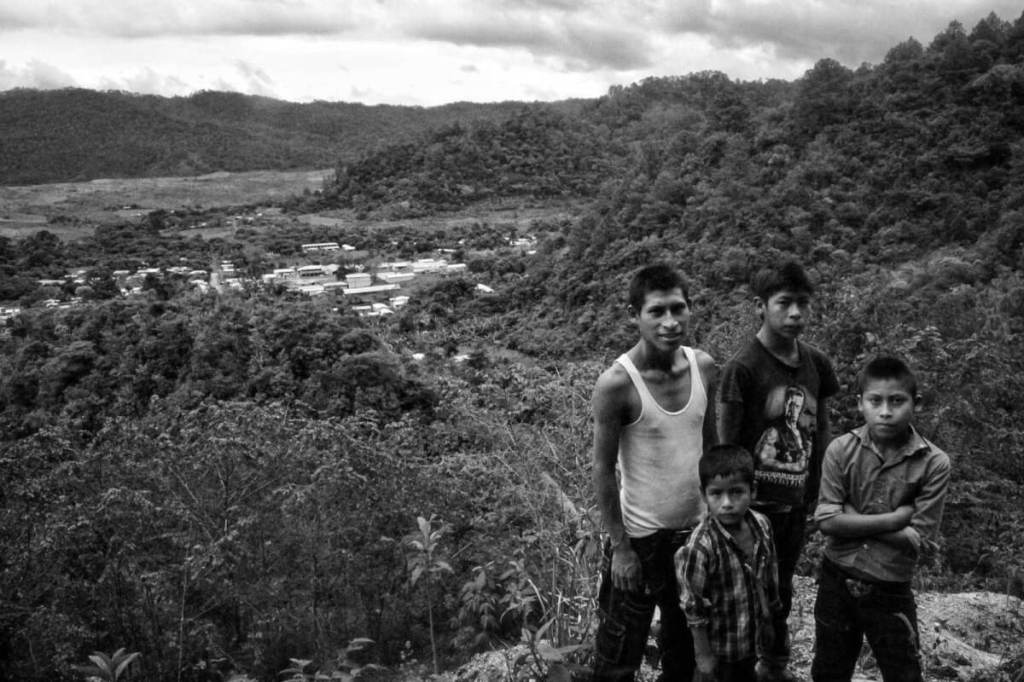

It’s night at the end of 2022. A half-moon hangs over us. In the backyard of his plot the family gathers to talk with visitors. Around a bonfire, two board benches and two stool-like logs form a circle. Seated very formal and hospitable are Javier, Magda and their offspring of daughters, sons, a grandson. Anselmo, veteran Zapatista miliciano,[1] father and neighbor of Javier, soon joins.

Javier leans on a couple of logs, at his feet a short, pointed machete, almost a knife or small sword.

“If this machete could tell everything it has seen. It was my dad’s when the war started.

Anselmo, in his baseball cap, nods with a brief sigh in Tseltal. He laughs like one who peers into a pit of inexhaustible memories.

Jonah, the little boy, great-grandson of Anselmo, still shows signs of mute activity. A few steps away are the two stick bars between stakes that serve as a walker to teach you to walk. In the arms of young Nely, he is a fourth-generation Zapatista who soon falls asleep in his mother’s milky sea.

The night of the Zapatista National Liberation Army’s Uprising Javier was 10 years old, Anselmo about 30 years old and a miliciano. He speaks little, and half in Tseltal, but makes it clear that he had to remain in the rear guarding the women, the elderly and the minors, and did not participate directly in the fighting in the city of Ocosingo on the first days of January 1994, where he did lose his little brother.

“The little brother carried his machete like this but he wasn’t lucky and didn’t return,” says Javier. Other comrades did, and they told how they were tucked behind some sacks in a ditch when the armies arrived. They saw the soldiers’ legs, they unleashed a machete blow at them, they fell and then quickly drew their weapons.

As part of the conversation, Magda cuts splinters from a piece of ocote wood with the same old machete of so much use and so very sharp. Someone says that it also serves to shell corn.

Laugh.

The lands where this autonomous community sits were part of a large cattle farm until 1993. The owner, from Ocosingo, never returned. Their cows and land remained, badly battered.

“Pure pasture land,” Magda recalls dreamily.

For three decades now, the recuperated lands have served better for milpa, acahual (fallow land), vegetable gardens, banana groves. A few lands remained for pasture. There are much fewer cows here than before, and few horses, the pasture is small. They have several clean springs on the hill.

Javier was a child that night and remembers his fear:

– We only saw how the compas went to war. We went to the shelter of the mountain. We got into a cave; it was very cold. My dad was one of those who took care of us in the mountains. Even before that day, we children were afraid when soldiers began to pass by, looking for the guerrillas who had surprised them in May in the Sierra Corralchén. It was in the news. The soldiers went all over the cañadas (canyons) and it seemed that they were going to go into the houses. After the war it was different, we had our army to defend us, and we no longer felt the same fear when they patrolled.

However, Javier acknowledges that with “Zedillo’s betrayal,” the military occupation in February 1995 was also very traumatic. They took refuge in the mountain again, but this time they had with them their own army, as they do now.

He adds that everyone knew that the uprising was coming weeks before. They began to take a lot of meat from the farmer, who sold it or trusted it to peasants and laborers and then forced them to pay, very scumbag. But people already knew about the war and that they wouldn’t need to pay him. Laughter and sparkling comments follow in their language.

“When the war started, we had eaten a lot of meat,” Javier says jovially, as a prank.

The memories of those days and nights that are now part of Mexico’s history led him to the news that the combatant compas brought in the days that followed, the epic or tragic stories that would resonate in the mountains, valleys and ravines in the months and years to come.

-Two compas who were from Altamirano got lost on their return from the taking of San Cristóbal and came out through Chanal. They were only carrying their machete. They met some people and asked them the way to their community and they said yes, we’ll guiden you right now, and two started walking with them at night. The compas were looking at their milicianos’ report and the people saw it. The compas confided, they took them further, and suddenly one of the people hits one of the comrades with the machete from behind in the neck and cuts off his head. That’s how it was, hanging forward. The other comrade sees that they are being attacked and defends himself with his machete, kills one of those accompanying him, but the other one goes for machete blows, cuts off his arm. The compa starts running with his arm hanging. At last, he runs into his platoon that was looking for them. They took him away and were able to heal his arm, he was maimed but alive.

This bloody tale opens the range of conversation to stories, dreams and stories of apparitions, where Javier’s children also participate. They invoke the Sombrerón, who is presented in different ways. Sometimes he whistles at the horses, takes them to the hill, braids them and lets them return. The braid gives more life to the animal, one cannot undo it.

They also tell of Señora Cortada, with her stump of a leg, who sits on a standing log like those we occupy tonight. And that the Sombrerón, if he takes you, puts your clothes back on inside out so you can come back.

“A disheveled girl appeared here in the yard. Only my mom saw her. She passed right here through the entire patio, screaming, and even Canela (the nice lame dog who now dozes around here) followed in her footsteps, says Javier.

Nely then reveals the kind of nightmares they give her teenage brother Antonio, who laughs shyly next to her.

-One night he got up sleepwalking repeating: “Uncle’s tacos belong to someone, Uncle’s tacos belong to someone. “

The remembrance is hilarious for everyone, except Antonio, who smiles wishing he would be swallowed by the earth.

Such was the family box painting that I witnessed and heard, I was lucky, somewhere in the Lacandón Jungle a few nights before the 29th anniversary of the Zapatista uprising that shook these peoples in 1994. In the background, on a wall of the wooden house cleanly painted green is a red star and reads in large letters “E.Z.L.N.”

In the various rebel communiqués, as made clear by the signs on their edges or the murals on some houses, regularly made of wood and in good condition, although they contrast with the constructions of material that mostly belong to the families that accept the government programs. In Javier’s community, this difference is less evident, unlike other parts of the vast indigenous region of Chiapas where people live in rebellious autonomy.

In Los Altos and other parts of the jungle, inequality manifests itself much more markedly, especially in San Juan Chamula, Chenalhó and Las Margaritas, where illegal businesses and official support have created a kind of middle class or even indigenous bourgeoisie throughout the recent decades of persistent political and economic counterinsurgency policies.

Javier is clear that living autonomously and being Zapatista implies an additional effort. But it’s worth it. He and his family are not alone. They live in dignified conditions, even with room for good taste details and savoir vivre, where hospitality and joy fit. Having dared to rise up against all possibilities, take back the lands of his native land, defend them and work them to sustain autonomy all these years, fills Javier with pride.

What he still does not know, or does not reveal, is whether there will be a party or assembly in his Caracol on New Year. At least that’s what he says, you see that the Zapatistas are always mysterious.

[1] Milicianos in the EZLN are similar to a National Guard. They are civilians, but have military training and live in the civilian communities. Milicianos participated in the 1994 Uprising.

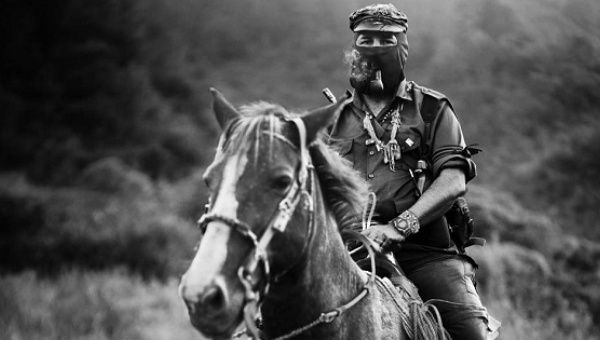

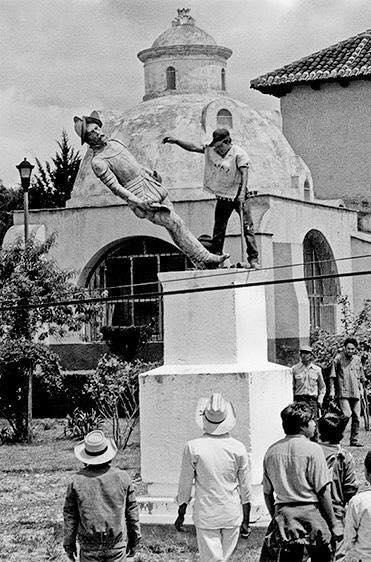

[2] There are no captions under any of the photos used in the original piece. However, some of the scenery looks very familiar to those of us in the Chiapas Support Committee who have often visited the Zapatista Caracol of La Garrucha.

Originally Published in Spanish by Desinformémonos, Monday, January 2, 2023, https://desinformemonos.org/la-memoria-de-los-machetes-de-la-guerra/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The “national security” declaration for the Maya Train favors the violation of human rights

The “national security” declaration for the Maya Train [1] “has the potential to allow that human rights abuses” are maintained, and “also undermines the purpose of inclusive and sustainable social and economic development,” said the chair of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights.

By: Gloria Leticia Díaz

Mexico City (apro)

Independent experts from nine special rapporteurships and the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, warned of “threats and attacks” against human rights and environmental defenders, given the declaration of a “national security project” that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador awarded to the Maya Train, as well as the participation of the Mexican Army in the construction of one thousand 500 kilometers in the Yucatan Peninsula.

In a statement dated in Geneva, Switzerland, the experts expressed concern about the danger that the construction of the megaproject will cause to the “rights of indigenous peoples and other communities, to land and natural resources, cultural rights and the right to a healthy and sustainable environment.”

For Fernanda Hopenhaym, chair of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, the declaration of national security “not only has the potential to allow human rights abuses to remain unaddressed, but also undermines the project’s purpose of bringing inclusive and sustainable social and economic development to the five Mexican states involved.”

The expert considered that “the increasing involvement of the army in the construction and management of the project also raises great concern.”

Concerned about “the lack of due diligence on human rights,” for the experts “relevant companies and investors domiciled in Spain, the United States and China cannot turn a blind eye to the serious human rights problems related to the Maya Train project,” estimated to cost 20 billion dollars.

The specialists pointed out that the government “must take additional measures to guarantee respect for human rights and the environment” and rejected that the national security status “does not allow Mexico to evade its international obligation to respect, protect and fulfill the human rights of the people affected by this megaproject and to protect the environment in accordance with international standards.”

They called on the government to “ensure meaningful participation of affected communities and transparency in human rights and environmental impact assessments prior to any future decisions related to the project, as key elements to identify, prevent and address any other negative impacts.”

They added that the free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples must be respected “and the actual and potential cumulative impacts of projects must be assessed in a transparent manner, in accordance with international human rights and environmental standards.”

They urged companies and investors to “take appropriate action and exert their influence to ensure that human rights due diligence processes are conducted in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. “

The position was signed by the other members of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, Pichamon Yeophantong, Eizbieta Karska, Robert McCorquodale and Damilola Olawuyi.

Likewise, the Special Rapporteurs on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Francisco Cali Tzay; on the Right to Development, Saad Alfarargi; on the Field of Cultural Rights, Alexandra Xanthaki; on the Right to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association, Clément Nyaletsossi Voule; on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, Margaret Satterthwalte; on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, Mary Lawlor; on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, Irene Khan; on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Ashwini K.P.; and on Human Rights and the Environment, David R. Boyd.

Note:

[1] Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), President of Mexico, declared the Maya Train a National Security Project on July 25, 2022 in his morning press conference: Consequently, Mexican courts cannot entertain lawsuits filed to stop, temporarily or permanently, the lack of indigenous consultation.

Originally Published in Spanish by Proceso, Wednesday, December 7, 2022, https://www.proceso.com.mx/nacional/2022/12/7/la-declaratoria-de-seguridad-nacional-del-tren-maya-favorece-la-violacion-de-derechos-humanos-expertos-de-la-onu-298317.html and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work with the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

Indigenous women in Chiapas suffer 77% of maternal deaths in the country

By: Yessica Morales

Providing access to health services for vulnerable populations is a priority in the universal health coverage plan (UHC), announced researchers Clara Juárez Ramírez, Alma Sauceda Valenzuela, Aremis Villalobos, and researcher Gustavo Nigenda.

In Mexico, they emphasized that indigenous women in Chiapas suffer 77% of maternal deaths in the country. There are various factors: cultural barriers, which make access to health care services difficult for indigenous populations.

For their research, selected two Mexican states as intervention centers for two different models of obstetric care. That is, rural and indigenous communities in Oaxaca for the standard (government) model of care and a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) implemented a model of care in Chiapas. [1]

Thus, they explained that the standard model of care provides primary health care services through community health centers. The number and type of professionals depend on the population of each locality.

This model also includes health clinics, a medical center run by community health workers and mobile medical units. In the community, health workers, midwives and special brigades of the project identify pregnant women to attend prenatal consultations.

Meanwhile, the NGO model implemented by Compañeros in Health, is a public-private initiative offers services in public units, in which community volunteers are included who accompany the mothers in order to support them and a maternal health committee responds to obstetric emergencies.

At the same time, it offers ambulatory services, medications and staff trained to supervise the technical aspects of care. In both models, women must pay to travel about 30 to 70 kilometers, in order to access a secondary level of care (hospital). In cases of obstetric emergencies, hospitals provide ambulances, if available.

In the standard model, 15% of women do not start prenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy and 28% register complications during pregnancy.

The women did not seek care in time due to economic, linguistic and cultural barriers, and were unable to make decisions on their own, the researchers added. [2]

In the NGO model, 98% of the women began prenatal care during the first trimester and 29% had managed home births with midwives, health companions and midwives.

The main difference between the two models is that the NGO model adopts a rights-based approach, which emphasizes freedom of choice and allows women to choose their position during labor and the place for the birth.

Women value the freedom to choose, they felt they had adequate information and could make informed decisions about other sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, such as family planning, Juárez Ramírez, Sauceda Valenzuela, Villalobos and Nigenda stressed.

In addition, they noted that health workers reported a lack of equipment in both the NGO and government models, and that women in general perceived the former model to be better.

Travel time to a secondary level of care was similar in both models. However, in the NGO model, there were compañeras who supported the process.

The World Health Organization announced that, every day, about 830 women die worldwide from complications related to pregnancy or childbirth.

On the other hand, the percentage of reported abuse was higher in the standard model (28%) than in the NGO (15%). Both provide a place for women and families to wait during childbirth.

Similarly, in the NGO model, accommodations are offered to companions, while in the standard they only offer women from remote communities and it is not enough.

Given the above, the researchers highlighted the achievements of both models, the NGO model offers women the freedom to choose the type of provider, center and delivery they prefer, which translates into better sexual and reproductive health outcomes, including family planning decisions.

In this model, health companions support women through counseling and assistance with referrals, and women perceive it as a better experience.

The respectful model of childbirth allows women to make decisions throughout the process of pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum, and promotes alternative practices to the traditional model of care, based on scientific evidence, said Juárez Ramírez, Sauceda Valenzuela, Villalobos and Nigenda.

Notes:

[1] Those Chiapas women who belong to the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) receive health care services through the Zapatista Health Care System, which includes clinics, micro-clinics, ambulances, midwives, doctors, health promoters and a women’s hospital in La Garrucha.

[2] Chiapas is considered the poorest state in Mexico. Three quarters of the population in Chiapas continue to live in poverty and a third of the total population of Chiapas live in extreme poverty.

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo, Monday, December 5, 2022, https://www.chiapasparalelo.com/trazos/tecnologia/2022/12/77-de-las-muertes-maternas-en-el-pais-se-producen-entre-mujeres-indigenas-de-chiapas/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Capitalism in criminal mode

By: Raúl Zibechi

In Latina America a criminal or mafia capitalism is expanding geometrically, in whose practices the differences between formality, informality and crime dissolve, as Peruvian researcher Francisco Durand maintains and how he has previously analyzed the Argentine Marcelo Colussi (https://bit.ly/3YLq98t).

Each time we have more data and studies that evidence the modes in which this predatory and criminal capitalism operates that, evidently, is the form that the system assumes in this period. The Quehacer magazine, Number 10, from the Desco Center in Lima, highlights in its July edition that illegal gold mining exported no less than 3.9 billion dollars in 2020, exceeding that of drug trafficking (https://bit.ly/3Z3gU3E).

In parallel, Bolivian Senator Rodrigo Paz points out that his country “is besieged by the gold, contraband and drug trafficking mafias,” which add up to the overwhelming figure of 7.5 billion dollars (https://bit.ly/3GmGlWzx). Drug trafficking contributes $2.5 billion a year, smuggling $2 billion and gold $3 billion. “The government, not being able to access external loans, lets these resources flow because they move the national economy,” he tweeted.

To get an idea of the importance of these figures, one must compare the $7.5 billion of illegal economies with the country’s total $9 billion exports. An incredible proportion that reveals the importance of mafia economies. Illegal gold has displaced drug trafficking in both countries, even though Peru is the world’s second largest producer of coca and cocaine in the world.

Most significantly, however, is how the illegal gold circuit works until it becomes legal gold. In Peru alone, there are 250,000 informal or artisanal miners who live in terrible conditions, are extorted and violated by intermediaries, until they reach the collectors. Legal and illegal miners participate in the extraction and commercialization process, with a fine dividing line between the two, since often the same collector buys in both markets.

Processing plants usually have double accounting, to access both the legal and illegal mineral. Gold converted into bullion or jewelry leaves for the two most important final destinations: Switzerland and the United States. The former imports 70 percent of the world’s gold. Bolivia and Peru produce almost 30 percent of gold illegally, a portion that reaches 77 percent in Ecuador, 80 in Colombia and 91 in Venezuela, according to the book Non-formal Mining in Peru (https://bit.ly/3YTYG4w).

This book reproduces a fragment of the work of the Swiss criminologist Mark Pieth, who highlights the contrast between La Rinconada, in Puno, “at more than 5 thousand meters high and with temperatures of minus 22 degrees, where 60 thousand gold prospectors squeeze into a town that 25 years ago was home to only 25 families. “

In that village “an unbearable stench of urine and human feces” dominates and the living and working conditions are “horrendous.” This reality is contrasted with “the glamor of gold in Switzerland,” where the Swatch watch company “spends 50 million Swiss francs annually, just to present its new gold watches, and beautiful models present jewelry for the enjoyment of those who can afford them” (p. 73).

Mafia capitalism causes enormous environmental and social damages, such as pollution and deforestation, homicides and disappearances, rapes and femicides, perpetrated by the mafias. One of its consequences is human trafficking for various purposes: sexual and labor exploitation, sale of children and organ trafficking. In mafia capitalism, people are just another commodity that can be torn to pieces with total impunity by state complicity.

Finally, we would have to answer a question that allows us to complete the picture, one that researchers in general do not ask: what is the State that corresponds to this mafia capitalism, which destroys everything to accumulate more and more capital?

It is a state for war, for dispossession against those below. But it has a peculiarity that differentiates it from the dictatorships that devastated our region: it’s painted with democratic colors, it calls elections although there are fewer and fewer freedoms, since monopolies block freedom of information and expression. In short: a criminal-electoral State.

Those who pretend to be a government must know that they will administer a criminal and predatory capitalism, impossible to regulate. That’s why the progressive rulers continue with extractivism and large infrastructure works, and look the other way when the murders of social leaders take place.

Looking aside is a way of letting go, as Switzerland does when it imports gold bathed in blood and death. Asked why Switzerland continues to import this gold, Mark Pieth concludes: “They want to do trade, to make an island of pirates” (p. 74).

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Friday, December 30, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/30/opinion/019a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Zapatismo impacts processes of autonomy in Latin America

An interview with Raúl Zibechi

29 years after the EZLN Uprising, the journalist and popular educator Raúl Zibechi evaluates the validity of the Zapatismo of Chiapas in the social and indigenous movements of Latin America and the processes that they experience before the progressive governments today.

Text: Daliri Oropeza Alvarez

Photos: Pedro Anza and Isabel Mateos

MEXICO CITY – Raúl Zibechi is a popular educator, journalist and writer who lives in Montevideo, Uruguay -where he has his library – when he isn’t traveling in Latin America. He is part of the Desinformémonos team, and collaborates in several media such as La Jornada, in Gara or Brecha, a media created by Mario Benedetti and Eduardo Galeano.

Zibechi is a referent for the analysis of anti-capitalist movements. For him, what’s important about the Uprising of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) in 1994 and what has been constructed in these 29 years in Chiapas is “showing that it’s a possible path,” to talk about autonomy.

He takes stock of the Zapatista Journey in Europe, the solidarity and horizons it opens up in Latin America for social movements. At the same time, he talks about the social context for indigenous movements with progressive governments, “they embody a possibility and in turn a risk,” he says in an interview.

He gives an overview of how progressive governments have people from the struggles in their ranks and this implies a risk for social or indigenous movements.

The journalist has closely followed the process of Pueblos Unidos, Nahua communities that united for water from the Cholultec region in Puebla, who closed a Bonafont plant and managed to recover water from their own wells.

There, in the closed Bonafont plant, he gave workshops and presented books. Although they were evicted, Zibechi returned this 2022 to present his book Other Worlds and peoples in movement. Debates on anti-colonialism and transition in Latin America.

In an interview he describes how the processes of dispossession, whether by corporations or States, cause division in indigenous peoples or social organizations, and talks about avoiding confrontation, given the difficulty of recovering the social fabric.

He assures us that we cannot forget that the subjects of decolonization are the peoples. He emphasizes that it’s important to think collectively and Zapatismo has stood out in that, in the simultaneous doing-reflection.

He participates in the interview from Montevideo, where he participates in a movement called Popular Subsistence Market, a collective of 53 nodes in networks dedicated to the community purchase and distribution of food that they buy from recovered factories, from peasants directly, or from production cooperatives.

The uprising and its contagions

—A 29 years later, why is it important to remember the Zapatista Uprising?

—It’s important because it marks a watershed in Latin America and the world. But we are going to stay in Latin America, at a time when real socialism had fallen. Between 1989 and 1991 there was an implosion of Soviet and Eastern European socialism and no social changes were in sight.

There was a complete triumph of neoliberal capitalism in the world. ‘The Commodity Consensus’, as an Argentine sociologist calls it. That on the one hand, and on the other hand, the vociferous advocacy of native peoples, in this case the peoples with Mayan roots, marks a turning point in what previous struggles used to be, they placed autonomy in a prominent place. The construction of autonomies instead of the struggle for state power.

Already in 1994, these two elements mark the irruption of a revolutionary force and in turn the collective subjects that sustain them: the original peoples.

How does the Zapatista uprising affect or favor social movements in Latin America today?

In Latin America, Zapatismo had a very strong imprint in the early years, logically. Then that imprint changed in intensity but today as almost 30 years have passed since “Ya Basta!” we have in Latin America, including Mexico, a large number of autonomous experiences … that I would not describe as daughters of Zapatismo but traveling similar paths.

We see the Mapuche People or different variables of the Mapuche People in southern Chile, in southern Argentina; the Nasa in southern Colombia, in Cauca; the birth of two autonomous territorial governments of the peoples in northern Peru: Wallmapu and Wampis, which are formed in the last six, seven years, in 2015 the Wampis, in 2021 the Wallmapu.

Twenty, up to 28 autonomous processes in the Brazilian legal Amazon of autonomous demarcation of territories; processes such as those experienced by Cherán in Mexico; processes such as those of Guerrero and those of Oaxaca, which some already came from before as the community autonomies of Oaxaca, but that are strengthened in this period of the 90s and take their own paths, naturally.

Zapatismo impacts the autonomous processes, it doesn’t direct them at all, because that’s not its objective, and also autonomy does not admit that others direct you, right? Autonomy is autonomy, so totally. Then everyone takes their own paths.

We also have autonomy and urban autonomic construction processes more or less known in different parts of the world and Latin America. And this seems to me to be very important: to create and confirm that we are in a process in which there is not only a part of the left and the movements that bet on the conquest of state power, but there is another part that sometimes collaborates or not, or are distanced. But there is another part of that left, from below, that fights for autonomy.

Something similar happens in the women’s movement, in one part they are more attached to state initiatives and another part more than linked to autonomy projects or autonomy processes. A similar thing happens among campesinos, among the black peoples who are at this moment, both in Brazil and Colombia, in processes of expansion of their initiatives.

It could be said, then, that the EZLN Uprising in ’94 and what was built as a result of Zapatismo, is a kind of detonator to make visible or proclaim these autonomies, which in themselves were already there, to infect them…

“Yes. Those that already existed and infect others that did not exist and show that it’s a possible way.

I do want to emphasize that what you call a detonator or a driver of these processes, is not in relation to direction. There is no one to direct these processes because autonomies are naturally self-directing, right?

Looking at Latin America

—It’s been a year since the Zapatista Journey for life where two delegations, one maritime, one by air traveled to another geography that is Europe. What horizons does this experience open in Latin America?

—I participated in exile in the 80s when the Uruguayan dictatorship in Europe, in the Spanish State, in processes of international solidarity.

What the Zapatista tour does is bring about a change in the political culture of solidarity. Not to provoke. To show that another culture of solidarity is possible because I remember in my life leaders, especially of the Central American guerrillas, who visited Europe; commanders, to meet with European political leaders. It was always mediated by fundraising, right, material support.

In this case what there are: women, above all, men, girls and boys from the communities and peoples with Mayan roots who visit another continent and meet with other people from the Europe of below.

It shows that another type of bond is possible, another type of relationship that does not go through the styles of the old political culture and is, to put it in some metaphorical way, an embrace between people and peoples from below. This is important because it also sends a different message that it is possible and necessary to carve out another political culture even in international relations.

This was left there, which people then pick up. I find it interesting to note that there are other ways and that they were shown. Other ways of doing solidarity, I call it political culture but there is no reason to call it that. Everyone calls things as they see fit.

—Now there are more countries with progressive governments in Latin America, what does it mean for indigenous movements on the one hand and for social movements on the other?

Well, you know that I am very critical of progressive governments. The ones I know the most, logically, are those from the Southern Cone: Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile… They embody a possibility and at the same time a risk.

The progressive government of Gabriel Boric sent more armored vehicles and more soldiers to Wallmapu, Mapuche territory, than the neoliberal government of Piñera, and militarized Wallmapu. That shows the risk, right? of the militarization of indigenous territories.

In turn, Lula, in his first two governments, advanced the enormous infrastructure work of Belo Monte, the third largest dam, an initiative that not even the military of the Brazilian dictatorship of 64 to 85 could carry out due to the opposition of the peoples of the Amazon, of the native indigenous peoples of the Amazon.

One says: Is Lula or Bolsonaro better? Obviously, I prefer Lula to be there than Bolsonaro, but that cannot obscure the enormous risks that the existence of progressive governments that are thriving represent for the movements. For the movements they have a risk, because many of them have been with the peoples, many of their cadres, especially in the media, have participated in the struggles of the peoples and when they go to the government, they take that knowledge to the government, then they can work better with them.

Now Lula is going to create the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, of Original Peoples, because they were the spearhead of the struggle or resistance to Bolsonaro. There is already a whole mechanism created so that the leaders of a good part of these peoples are inserted into the ministerial structure, with which the struggle and organization of the peoples will undoubtedly be weakened.

There are lights and shadows, and the shadows for movements, for indigenous peoples, are very great risks because once a people, an organization is inserted into the institutions and co-opted by them, it is very difficult to recover autonomy.

Recovering social fabrics

“What a panorama! There is a concern expressed in several indigenous peoples about the division caused by voracious capitalism or governments, about dispossession. What alternatives do social or indigenous movements have in the face of what you were talking about, the use of codes of struggle by progressive governments, in the face of division?

—I have no alternatives. What I see at the more macro level is that the world’s ruling classes and international corporations have learned a lot from the people.

There we have the case of Soros and the Color Revolutions, which are found in many places to such an extent that one doubts. We won’t know if it’s a legitimate movement or if it’s a movement that started out legitimate, regardless of whether it agrees or not, but then was manipulated by the media and the right. Something like this happened in Brazil in June 2013.

A mining corporation, for example, arrives in Peru or Ecuador, or in any country: Argentina, Chile, regardless of the government, it arrives in a community and that community is offered “aid” for schools, for sports centers, for a number of initiatives. It neutralizes criticism of this mining venture.

So, the result is what you mentioned: a division is promoted in the communities, by that intelligence acquired by the big corporations: the mining companies, Monsanto, the soy companies, etc. and a process of division of the struggles begins because there are always people from the communities who, even without bad intentions, see that the presence of this mining company or this international company is favorable to their interests.

This division inevitably weakens the struggle, the resistance. So, what I believe is that we are facing a period in which capitalism, the knowledge of capitalism, has managed to generate widespread confusion among the popular sectors and communities and in this confusion the extractive projects deepen and accelerate, and this is very difficult to reverse.

The only way to reverse it is with a lot of patience. With a lot of acceptance that the community is divided and that they are not good and bad. Sometimes there is someone bought by power, of that there is no doubt. But you can’t simplify it between good and bad. What ends up happening is a situation in which the collective fabric of communities ends up being hurt, torn.

And repairing those tissues is not easy. Sometimes you can’t. Sometimes it takes a lot of time. But we must avoid confrontation in any case, because except for a minimum, a very small minority of people who obtain positions or money, that division cannot be judged because what is acting are very strong powers.

—In your recent book, “Other Worlds and Peoples in Motion,” you place peoples as collective subjects of knowledge and critical potential, as a subject within history with an emancipatory potential.

—In this book I try to show, to know one: that decolonization or decoloniality, as academia maintains, has subjects that are the peoples, who are collective subjects.

Because sometimes it would seem that there is a lot of confusion in academia, like everywhere, which is not something special. But what one can see is that it’s not clear from the writings of scholars who the subjects of decolonization are. And they are the peoples.

That is a first theoretical and important question, because otherwise the peoples would be the object of study and I believe that they are collective subjects in thought and action.

And the second thing is to show how in this completely new period, Immanuel Wallerstein says that we are navigating seas for which there are no maps because we are in a systemic crisis of capitalism, of neoliberalism, and before a civilizational crisis that includes environmental and other facets.

The peoples, unlike the old labor movement, are in turn resisting the model but creating new things in health, in education, in justice, and not only in Chiapas.

I believe that Zapatismo does both: create a new world and reflect on it. It has both facets and in that sense it shows an important plus because, although I believe that the creations of a we are already the heritage of many native peoples, blacks, peasants and even urban peripheries in Latin America, the deep reflection on this is not yet the heritage of all movements.

But yes, Zapatismo has excelled in this: in doing and reflecting, in reflecting on what is done and this is a very important thing because we need to think collectively in order to continue growing.

Originally Published in Spanish by Pie de Página, Saturday, December 31, 2022, https://piedepagina.mx/el-zapatismo-impacta-en-los-procesos-de-autonomia-de-america-latina-raul-zibechi/ and Re-Published with English translation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The EZLN commemorates 29 years of struggle with a call to new generations of rebels

With dances and slogans, members of the EZLN ratified their struggle that began on January 1, 1994 and called on the new generations of rebels not to forget those who gave them their lives.

By: Isaín Mandujano

SAN CRISTÓBAL DE LAS CASAS, Chis (proceso.com.mx)

Between dances and slogans, milicianxs and support bases of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) ratified their struggle that began on January 1, 1994 and called on the new generations of rebels not to forget the dead who gave their lives since “the organization” was conceived in the deepest recesses of the Lacandón Jungle.

In the interior of Caracol VII Jacinto Canek, located in the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Indigenous Center for Integral Training AC-Universidad de la Tierra Chiapas (Cideci-Unitierra Chiapas) north of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, some two thousand masked members of the EZLN gathered.

After honoring the Mexican flag and the EZLN fighting flag, a black flag with a red five-pointed star in the center, one of the commanders of the armed group took the floor to recall what happened that night between December 31, 1993 and January 1, 1994. as well as the days of war that came afterwards, in which there were many dead, wounded and missing.

While they allowed access to journalists, they did not allow photographs, videos, much less record audio of the speech given only in Tsotsil. Except for the slogans that were in Castile, as they refer to the Spanish language.

The spokesman of the event thanked everyone for their presence to remember this date of the armed uprising “against the bad government.” But above all, he said, remembering the men and women who lost their lives “in those difficult days.”

“Let’s remember that this fight is a fight against the bad government, so let’s remember that we must be and continue to be organized, developing what we are doing. Let us all continue to work in unity, let us all continue in the organization because this is a long journey that has been made. It is a job that those who have already died left and we must continue, to continue remembering it,” the rebel commander said.

He pointed out that they continue to demand justice for their dead and disappeared, and that they did not stop shouting it because each and every one of those crimes that remain unpunished must be clarified.

He asked those present not to forget the dead, because thanks to them they have been able to continue fighting for a better quality of life and outlined that their levels of government are now determined by three hierarchies, by groups, by zones, and in each of them each of the men and women have an important role.

“I ask the new generations to learn the form of organization, to learn to work within their towns and communities so that they do not have to migrate to other countries or states to get work, because within organizations there are also jobs that are very important. That is why it’s relevant that the new generations learn all that, so that the organization can continue,” he added.

“Don’t change your way of thinking, keep it up, let’s keep thinking like this because so far the organization has walked well and we follow the legacy and the thinking of those who have already died. And while it has been transformed, this has been in the community, so it’s important that we continue to learn all this, “he said.

“¡Viva el EZLN! ¡viva the 29th anniversary of the armed uprising!, ¡vivan the insurgentas!, ¡vivan the insurgentes!, ¡vivan las milicianas!, ¡vivan los milicianos!, ¡viva Subcomandante Insurgente Pedro!, ¡vivan all of the fallen!, ¡viva the resistance and rebellion!, ¡viva subcomandante insurgente Moisés!, ¡viva subcomandante Insurgente Galeano!, ¡viva Chiapas!, ¡viva Chiapas!, ¡Viva México!, ¡Viva México, ¡Viva México!”, were the chants at the end of the political event.

Then it gives way to the musical group that enlivened the dance, where men and women filled the sports field.

They were first born as the National Liberation Forces (FLN, Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional) on November 17, 1983 in the heart of the Lacandón Jungle. Later, in 1992, to attend the march on October 12, 1992, to celebrate 500 years of indigenous resistance, they called themselves the Emiliano Zapata National Campesino Alliance (ANCIEZ, Alianza Nacional Campesina Emiliano Zapata). But on January 1, 1994, the whole world knew them as the EZLN.

Originally Published in Spanish by Proceso, Sunday, January 1, 2023, https://www.proceso.com.mx/nacional/estados/2023/1/1/el-ezln-conmemora-29-anos-de-lucha-con-un-llamado-las-nuevas-generaciones-de-rebeldes-299540.html and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

EZLN, 29 years of persistence

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas

29 years have passed since the armed uprising and the declaration of war against the Mexican state of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in the mountains of Chiapas. Six presidents and nine governors later, and so much water running under the bridges at the national and local levels since that early morning of January 1, 1994, the challenge posed by the insurrectionary Mayan peoples remains. And its bold and functional autonomy has just turned 28. On December 19 of that same year, the creation of the first 38 rebel autonomous municipalities was announced.

What was born as an experiment in indigenous peoples’ self-government, which the State has never recognized and for seasons has openly fought via the armed forces and police at all levels, still stands when 2023 arrives. The rebellious municipalities persist, different from those at the beginning, but the same. La Jornada toured the regions of some of the at least 12 current Zapatista caracoles and was able to observe the vitality of this autonomy.

In 1995, after the military occupation of the Zapatista communities and, on orders of President Ernesto Zedillo, destruction of the Aguascalientes in the Tojolabal community of Guadalupe Tepeyac, the EZLN created five Aguascalientes, and organized their autonomy regionally around them.

What began as an armed action, for many even suicidal, resulted in new forms of indigenous self-management against the grain of the rampant neoliberal Spring in which the PRI governments claimed to have lifted Mexico. After the San Andrés Accords in 1996, Zapatista autonomy was in fact confirmed by assuming as law the agreements signed and then betrayed by the Zedillo government. This autonomy was rightly seen as an obstacle to the transnational and national megaprojects to come.

Memorable are the police, military and paramilitary aggressions against the rebel municipalities. Tierra y Libertad, Ricardo Flores Magón, San Juan de la Libertad, San Pedro Polhó and San Pedro de Michoacán are among those that suffered the greatest violence and dispossession. Even so, these governments continued, establishing their own systems of justice, health, education, transportation and management of land and its products.

A large part of these autonomous spaces were, and still are, on land recuperated from the finqueros (estate owners) and cattle ranchers of the Lacandón Jungle after the uprising almost three decades ago. Many others are made up of communities in the traditional areas of Los Altos, the northern zone, the jungle itself and the border region of Chiapas. Choles, Tseltales, Tsotsiles, Tojolabales and Zoques who embarked on resistance.

Six-year term after six-year term, government projects and programs have sought to undermine economically and institutionally this unique indigenous autonomy in the world. In August 2003 another twist was known when the creation of the caracoles was announced, new centers of government in the five Aguascalientes that already existed. Thus, the Good Government Juntas were born, around which the Zapatista municipalities were reorganized.

The experience would be very useful to face the new government attacks after the “declaration of war” from the government of Felipe Calderón to organized crime, which in principle meant militarily surrounding the country’s indigenous communities and the virtual paralysis of the National Indigenous Congress. With Peña Nieto would come the Crusade Against Hunger, a new version of economic counterinsurgency. In 2019 and 2020, already in the period of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the EZLN established new caracoles and good government juntas, until adding at least 12, and a redistribution of its municipalities.

Now it’s the new state and federal governments of Morena that dispute followers by electoral means (to which the Zapatistas never go) and promote a renewed partisanship of municipalities and indigenous communities, as well as by economic means through social and welfare programs, to which the Zapatista resistance has remained impervious by peaceful and organized means.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Saturday, December 31, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/31/politica/008n1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Pablo González Casanova, a Latin American trajectory

By: Sebastián Rivera Mir*

In the 1970s, the Argentine dictatorship decided to outlaw hundreds of books analyzing the continent’s social and political conditions. On Sociology of exploitation, by Pablo González Casanova [1], they declared that it was a book that demonstrated “a form with undoubtedly dissociative tendencies, since they attack the structure of the State or one of its institutions, considering the need for its change by unacceptable means.” Why did one of the bloodiest dictatorships on the continent worry about the approaches of the Mexican historian and sociologist who was more than 8,000 kilometers away? How could a text of rigorous analysis of Latin America’s economic and social future be a threat to Argentine generals?

Beyond the anti-communist hysteria itself, these soldiers seemed to understand one of the main objectives of Pablo González Casanova at the time of carrying out his intellectual activity: it’s not enough to just understand reality, it’s essential to try to change it. His commitment to social movements, to revolutionary processes, cannot be dissociated from his rigorous and critical efforts to analyze political, cultural and economic problems. Of course, the impact of his proposals throughout the continent has ended up becoming a challenge for those who seek to curb democratic processes.

The Latin American gaze of González Casanova began to be cemented from his first steps in the academic field. Paradoxically, one of his first publications in El Colegio de México, where he studied for a master’s degree in history, focused on censorship implemented by Spanish colonial authorities in Latin America. The doctorate, carried out in France together with one of the leading historians of the time, Fernand Braudel, again led him to explore the activities related to the coloniality of thought, although this time from the perspective of the sociology of knowledge.

The need to rethink, from Marxism, those categories that explained the conditions of subordination of the continent led him to build, with a statistical rigor uncommon in the 60s, the concept of internal colonialism. It was a question of understanding how forces were articulated within our countries that contributed and took advantage of the relations of dependency for their own benefit. Like many of his works, it was also based on dialogue with other researchers and political actors. Different approaches were discussed in academic spaces in Brazil, Peru, Chile, Mexico, among other countries. Thus, the result was not a personal interpretation, but a true work of collective criticism throughout Latin America.

The process of conceptual and reflective elaboration of Pablo González Casanova has been accompanied by the creation of institutions that would allow these intellectual efforts to be sustained over time. At different times, he was linked to the Centro Latino-Americano de Pesquisas em Ciências Sociais (Clapcs; Unesco), the Latin American Association of Sociology, the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (Flacso), the Permanent Seminar on Latin America (Sepla), publishers such as the Fondo de Cultura Económica or Siglo XXI, the Salvador Allende Center for Latin American Studies, among other organizations. We could go on enumerating; However, what is relevant is to recognize that his commitment to institution-building has given density to the analytical exchanges required to face problems that often exceed national boundaries.

This last aspect allows us to understand the thematic breadth of his reflections, which have covered elements as diverse as democracy, militarism, peasant and workers’ movements, the constitution of states and uneven economic development. These problems, central to understanding the challenges faced in Latin America, have been part of Pablo González’s political career. For example, his support for anti-dictatorial movements led him to focus his analyses on the role of democracy in the region, or his collaboration with South American exiles pushed him to rethink militarism. Thus, as we have stated, their political practices, their theoretical works and their contributions from the academic field, have formed part of the same process.

That’s why it’s no coincidence that Chilean students at the end of the 60s took up thinking again about university reform, having their books reprinted in different parts of the continent or that even the Federal Directorate of Security continued its activities in support of the revolutionary movements in Cuba, Central America or Mexico. The trajectory of Pablo González Casanova in Latin America has allowed consolidating an alternative political thought and praxis, which continues to encourage the struggles for a different world. And this, as with the Argentine military in the 70s, constitutes a challenge for the defenders of the current neoliberal model.

* Professor researcher of El Colegio Mexiquense

[1] In April 2018, the EZLN named Doctor Pablo González Casanova a comandante in the Indigenous Revolutionary Clandestine Committee of the EZLN (CCRI-EZLN), Comandante Pablo Contreras.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Wednesday, December 14, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/14/opinion/022a1pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The return of the old mole

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

A ray in the darkness of Salinas neoliberalism illuminated Mexico from below on the night of December 31, 1993. At the sound of the drum of dawn, tens of thousands of indigenous Zapatistas militarily occupied the municipal capitals of the main cities of Los Altos and the Chiapas jungle.

Formed on November 17, 1983, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) grew for years in silence, underground, until the moment came to rise up in arms. The counter-reform to Article 27 of the Constitution raised the white flag of land distribution and the start of the North American Free Trade Agreement converted the country into “Maquilatitlán;” they left no alternatives on the horizon.

The first public indications of the insurgents’ existence appeared on the 22nd and 23rd of May 1993, when the Army found Las Calabazas rebel camp, in the Sierra Corralchén [mountains] of the Lacandón Jungle [1]. On May 24, soldiers surrounded the Pataté community, gathered its inhabitants in its center and, without a search warrant, went inside to search houses. They found a few low-caliber weapons used for hunting. Eight indigenous men were arrested. Later, they randomly arrested two Guatemalans who were selling clothes. They were charged with treason. The region became militarized and overflowed with new resources from the Solidarity Program. But then path of the rebellion continued.

A warning that something was happening in those lands could be seen in San Cristóbal de las Casas, on October 12, 1992. In anticipation of what would be common in other latitudes over the years, a contingent of the National Indigenous Peasant Alliance Emiliano Zapata (ANCIEZ) knocked over the statue of the conquistador Diego de Mazariegos, during the march to commemorate 500 years of indigenous, black and popular resistance. From then on, the ANCIEZ stopped acting publicly.

Out of the press’ spotlight, great transformations began to take place in grassroots organizations. Not a few democratic teachers had to leave their schools in Las Cañadas and moved to teach in other regions. In the assemblies of the cooperatives of small coffee producers, some of their leaders “disappeared” from the map, only to reappear after the uprising, no longer as coffee growers, but as Zapatistas. Others (many of them young) were absent for some time and returned with a surprising political formation. Several more, usually very active in the assemblies of their associations, visibly tired, stopped intervening in the meetings, while they dozed overloaded in the bundles of coffee. Later, it would be known that they used the nights to train in other tasks.

At the same time, many producers who for years had received credits from Solidarity to finance their crops and had religiously returned them, stopped paying them and used the resources for other things. There were not a few who sold their cows and pigs, nor those who stopped planting corn. They were preparing for something big. Meanwhile, communities voted to declare war on bad government.

The imminence of the armed uprising was an insistent rumor in Chiapas circles. There was talk that it would be December 28, April Fool’s Day. It was uncertain whether it would happen, its magnitude and the form it would take.

The Zapatista cry of “Ya Basta!” on January 1, 1994, shook the entire country and reached the most dissimilar corners of the planet. Its manifestations were as unexpected as they were diverse.

At the height of the conflict, the National Coordinator of Coffee Organizations (CNOC), with a relevant presence in Chiapas, became involved in the search for a peaceful solution to the conflict. Although it was composed mostly of indigenous people, its members did not usually identify themselves as such until then. But the uprising disrupted this dynamic and awakened in them an enormous pride of belonging to the original (native) peoples. At an assembly held in the old Ciudad Real (San Cristóbal), the teacher Humberto Juárez, a Mazatec president of the organization, unexpectedly began his speech in his own language, addressing the attendees as “indigenous brothers.” The change was remarkable. At meetings, Spanish was usually spoken and small coffee farmers referred to themselves as “fellow coffee producers.” Similar events took place throughout the country.

Some 28 years have passed. Since those dates, the Zapatistas have not only survived. They have constructed one of the most astonishing and surprising experiences in anti-capitalist self-government and self-management. They have renewed themselves generationally. They are an exceptional countercultural ferment and a source of inspiration for thousands of those who struggle for a different world all over the planet.

Revolution is the old mole that digs deeply into the soil of history and occasionally shows its head, said Karl Marx. As happened between 1983 and 1994, many of the transformations that the rebels have promoted from below go unnoticed today. Sooner or later, that old mole will come to the surface.

Twitter: @lhan55

[1] The Sierra Corralchén mountain range separates the Zapatista Caracoles of La Garrucha and Morelia in the cañadas (canyons) region of the Lacandón Jungle.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, December 27, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2022/12/27/opinion/011a2pol and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee.

Please consider making a donation to the Chiapas Support Committee in support of our work with the Zapatistas. Just click on the donate button. We appreciate every donation and will thank you from the bottom of our hearts.