Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Chiapas March for Alberto Patishtán’s Freedom

Tzotzils and Teachers March for Patishtán’s Freedom

** They ask the magistrates “not to continue staining his dignity”

** “Justicia in México is in reverse,” Las Abejas complaint

By: Hermann Bellinghausen, Envoy

Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, April 19, 2013

In an indigenous pilgrimage that was also a very well attended political march, the capital of Chiapas became familiar with, live and amplified, the clamor for the freedom of professor Alberto Patishtán Gómez. In a significant gesture of solidarity, more than 8,000 teachers from the democratic block of Section 7 (Local 7) of the National Education Workers Union followed the march of some 6,000 pilgrims, the immense majority of them Tzotzils, and at every moment supported the demand for freedom for the one who is, certainly, the most well-known and respected Chiapas teacher in the world.

At the doors of the Federal Judiciary, which remained closed, the Catholic organization Pueblo Creyente stated: “Señor magistrates of the first collegiate tribunal of the twentieth circuit, don’t continue staining his dignity, his prestige, keeping our brother a prisoner. The decision that you make will remain written in the historic memory of the Mexican people. Don’t repeat the same action that Pilate did to Jesus, knowing that he is innocent you wash your hands and deliver a death sentence.”

The column of some 15,000 people, which paralyzed the center of the city for more than three hours, first arrived at the seat of the Federal Judicial Power, located on a closed street, which was entirely occupied with indigenous people to the sound of flutes, guitars and drums, carrying the crosses of all the Acteal dead. Men and women from Pantelhó, Huitiupán, Simojovel, Chenalhó, San Andrés, Zinacantán, Huixtán, Chamula, San Cristóbal de las Casas and of course El Bosque, where Patishtán is from, didn’t stop repeating his name during the whole march. Hundreds of small signs showed his face over red.

Waiting on Avenida Central, thousands of teachers, who also were marching against labor and education reforms, supported their demands. With unusual generosity they accepted going behind the indigenous. The megaphones in their respective discoveries were saying: “We recognize Patishtán as one of us, we recognize his innocence, and we add ourselves to his protest against the justice system.”

A few kilometers from here, in Navenchauc, along the old highway to Los Altos, the President of the Republic was launching the National Crusade Against Hunger dressed in his Zinacanteco attire, (a PRI ritual) the same as the state’s governor and his Brazilian invitee Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as an honorary witness. Did what they were shouting along Avenida Central in Tuxtla Gutiérrez reach them, although it was as a vibration?

“Today the federal and state governments (new Pharaohs, Herods and Pilates) have proposed crusade strategies against hunger. There is no truth in their words. We believe and we are convinced by facts that it is a crusade against the hungry,” the Tzotzils added in their discourse.

“Our indigenous and campesino peoples yes we are hungry, but with truth and justice for the Acteal case, hunger for the immediate and unconditional freedom of our brother Alberto, hunger for the respect and love of our Mother Earth, hunger for the fulfillment of the San Andrés Accords, hunger for peace for indigenous peoples; not for the crumbs that the government gives to quiet their conscience, to not see the truth, to eclipse and bury the State crime committed in Acteal.”

At its turn, the Civil Society Organization Las Abejas, whose presence was notorious, demonstrated in front of the Government Palace, a few blocks ahead, its repudiation “of the massive release of the Acteal paramilitary murderers.” In a severe tone, Las Abejas sustained: “Justice in Mexico is reversed. In what kind of language must we speak so that (the powers) understand?

In front of the Government Palace, Pueblo Creyente repeated its message to the Chiapas magistrates who, in a few days, will have to resolve the freedom of the multi-named teacher from El Bosque, who today completes 42 years of age, 12 of them in prison: “Before these realities of injustices that the indigenous live, profe Alberto was struggling from his town and accompanied the people for a just and dignified life. The federal, state and municipal governments didn’t like the profe’s humanitarian work, therefore they sought him out for the crime, and he is sentenced to more than 60 years in prison for a crime that he did not commit.” To conclude: “No more innocent prisoners. No to the government’s repression of the teachers.”

——————————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Saturday, April 20, 2013

En Español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2013/04/20/politica/012n1pol

Paramilitarism, Armed Groups and Community Self Defense

[As this article explains, violence from organized crime and the Drug War in Mexico is rampant in a number of Mexican states. Some indigenous communities have policed themselves for some time, but more and more communities are now taking up their own armed self-defense due to the dramatic surge in violence. The governments fear this trend and are beginning to crack down on (arrest) some of the groups.CSC]

Paramilitarism, Armed Groups and Community Self-Defense

By: Gilberto López y Rivas

For years, the country has suffered a social war whose cost in human lives is now around 100,000 dead, the majority poor and young, while society is a prisoner of uncertainty about the future of the families –surely mortgaged by the 70 million Mexicans living in poverty–, and by the desperation of establishing that the PRI “alternative” means –in fact– the gatopardismo [1] in which everything changes so that everything stays the same (or gets worse).

In this lapse, armed groups have usurped the monopoly on violence, which supposedly corresponds to the State, and devastate the streets, businesses, barrios, communities, regions, and even complete states, which are abandoned in the defenselessness and at the mercy of their criminal actions. At the same time, in territories where the Mexican State has put into practice counterinsurgency strategies or an irregular war, paramilitarism has been activated, with the acquiescence, support and complicity of the authorities and furtively linked to the armed forces, police institutions or intelligence organisms. When I was a member of the Commission for Dialogue and Pacification (Cocopa), and in my capacity as rotating president, I presented in 1998 to the Attorney General of the Republic –with the advice of the lawyer Digna Ochoa– a denunciation about the existence of paramilitary groups, one of which was responsible for the Acteal Massacre. At that opportunity, the same attorney general Jorge Madrazo Cuellar told the members of the Cocopa about the presence in Chiapas of at least 12 groups that are euphemistically called “groups of civilians presumably armed.” A special prosecutor for the case was created, the same one that disappeared without pain or glory, years later.

Since those years, I have reiterated that the state grants a fundamental element for a perfect analysis cabal of paramilitarism, and I have defined paramilitary groups as those that count on organization, equipment and military training, those to whom the State delegates the fulfillment of missions that the regular armed forces cannot openly carry out, without implicating that they recognize their existence as part of that monopoly of state violence. Paramilitary groups are illegal and have impunity because it is convenient to the State’s interests that way. The paramilitary consists, then, in the illegal and unpunished exercise of state violence and in the hiding of the origin of that violence. Historically, paramilitarism has been a phase of counterinsurgency that is applied when the power of the armed forces is not sufficient to annihilate insurgent groups, or when their discredit obliges the creation of a paramilitary arm, clandestinely tied to the military institution. A clear example of this type of grouping is the dreaded White Brigade (Brigada Blanca), a criminal extension of the State during the dirty war, whose commanders were Colonel Francisco Quiroz Hermosillo, Captain Luis de la Barreda Moreno and Miguel Nazar Haro.

Although paramilitarism is tightly linked to counterinsurgency strategies, it can occur that the State uses –by omission, passivity or corruption of its officials– the armed criminal groups for their own purposes of social control, criminalization or violent aggression on opponents, passing through this way of state articulation, to also be constituted into paramilitary groups. This could be the case of the so-called guardias blancas, which in many rural regions formed the gunmen or armed appendage of landholders and regional oligarchies, and that because of class loyalties, the State has tolerated and protected.

When the State does not fulfill the legal and constitutional responsibility of preserving the security of the citizens or administering justice and, to the contrary por, uses the Army, police contingents and the judicial apparatus as a means of control and political-territorial intervention with the population by way of a militarization of society and venal justice at all levels, the emergence of mechanisms of self-defense and community justice of a varied nature take place that fulfill the functions that the State illegally alienates or disrupts. Experiences like the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities-Community Police (Coordinadora Regional de Autoridades Comunitarias-Policía Comunitaria, CRAC-PC), that which forms the defense of Cherán Municipality, Michoacán, the autonomous rebel zones protected by the EZLN and those emerged in other latitudes of the Mexican geography, articulated by the communities, which control and monitor them, without any relationship with the State but subject to internal regulations and principles like govern obeying, not only are legal and legitimate according to the Constitution and Convention 169 of the ILO, signed and ratified by Mexico, but rather constitute the only socio-political spaces where control has effectively been achieved over what’s called “organized crime.”

Therefore, greater conceptual rigor and institutional seriousness of organisms like the National Human Rights Commission would be hoped for before the natural proliferation of community self-defenses for supposedly “breaking the state of law,” when to all appearances it has been the State that systematically has violated it through the practices of forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, torture, corruption-penetration by organized crime of all the spheres of public power and the total inability on the part of the authorities to guaranty public security and the administration of justice.

What is also grave is the State’s pretention of submitting organisms like the CRAC-PC to governmental control, through laws and regulations that subvert the mandate of the assembly, to make official what is a service and break the very essence of the normative community systems.

———————————————————-

Translator’s Note: [1] Gatopardismo refers to a political situation in which there is apparent political change, but in reality nothing really changes. It literally translates into the brown cat, referring to the African leopard.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

March 29, 2013

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2013/03/29/opinion/015a2pol

Moisés, Another EZLN Comandante

Moisés, Another EZLN Subcomandante

By: Gloria Muñoz Ramírez

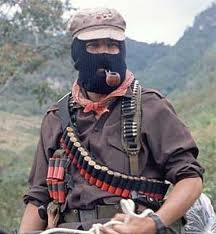

Visionary, military strategist, and organizer of the people, these are some of the characteristics of the new Subcomandante of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, its initials in Spanish). Known as Major Moisés in early January 1994, he would move to the position of Lieutenant Colonel in 2003. Today, Subcomandante Marcos, Zapatista military leader and spokesperson, introduced him as the new Subcomandante of the insurgent forces.

“We want to introduce you to one of the many “he’s” that we are, our compañero Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés. He guards our door and he also speaks using the words of all of us. We ask you to listen to him, which is, to look at him and so to look at ourselves,” said Subcomandante Marcos during the public announcement of the new appointment.

Moisés is one of the most well known insurgent commanders in the public life of the EZLN. On 16th February 1994, during the handing over of General Absalón Castellanos, the EZLN’s prisoner of war, he was seen for the first time heading what would be the first of the Zapatista public events after the beginning of the war: an act full of symbolism that was finalized with the exchange of the former Governor of Chiapas, known for his ruthless actions, for hundreds of Zapatistas taken prisoner during the first days of the war. The act was taken advantage of to make the ethical presentation of a movement that sentenced him to bear the forgiveness of those he had humiliated, imprisoned and murdered.

“I have come to hand over the prisoner of war, who is General Absalón Castellanos Dominguez. In a few words: The People’s Army, the Zapatista National Liberation Army, has complied as between warriors and rivals. Military honor has value, as the only bridge. Only real men use it. Those who fight with honor, speak with honor.” These were the first words which were heard from the then Major Moisés, in one of the most emotional events of these 19 years of struggle: the first presentation of the Zapatista support bases in Guadalupe Tepeyac.

Subcomandante Moisés came to the Zapatista organization, as he himself has said, in 1983. Of Tzeltal origin, he was sent to “the city” as part of his preparation and there, in a clandestine house, he met Subcomandante Pedro, who later became his leader, and for whom he would become his right arm. Afterwards, he would be very close to Subcomandante Marcos. Moisés was one of the people who opened up the Tojolabal canyon areas of Las Margaritas; he visited village-by- village, family by family, explaining the reasons for the struggle.

Of short stature, and with an enormous heart and political vision, always wearing his black military hat, with a sense of humor which does honor to the depth of the Tzeltal people, it fell to Moisés to withdraw at the side of Marcos during the government’s betrayal of 9th February 1995; this is why much of the literature produced during that period portrays them together, with him as squire.

Witness to one of the last meetings between Subcomandante Marcos and Subcomandante Pedro, his second in command, Moisés describes how the two commanders argued because both of them wanted to go to war. But both said the other had to stay behind, because if one of them fell the other would have to carry on. Both of them went out, the first one to the taking of San Cristobal de las Casas, and the second to Las Margaritas, where he (Pedro) was killed in combat the same morning. At that time, with uncontrolled insurgent troops, the now new Subcomandante assumed the command and control of the operation in the region.

Later on, after the handing over of General Absalón, the dialogues in the Cathedral, and the opening up of the territory in rebellion to civil society and the media, the vast majority of the Zapatista public activities moved to the Tojolabal canyon area, where Subcomandante Marcos appeared regularly alongside the then Major Moisés and Comandante Tacho, among other civilian and military leaders in the region.

During those first months and years, in addition to his work within the organization, Moisés appeared as the middleman speaking with a good part of national and international civil society; he provided media interviews explaining the beginnings of the Zapatista struggle, the content and motives of their peaceful and political initiatives, and, later, the functioning of the Good Government Juntas, of which he was the promoter of their first forerunner, the Association of Autonomous Municipalities.

In 2005, with the release of the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, he was appointed by the General Command to be in charge of international affairs, in a committee known as “La Intergaláctica.” During that period, while Delegate Zero was traveling the country with the Other Campaign, the then Lieutenant Colonel received visits from other countries and sent greetings to international meetings.

Known for his patience, openness and willingness, on the occasion of the 20th birthday of the EZLN, he said: “It is our way to first do the practice, then the theory. And so, after the betrayal, when the political parties and the government rejected the recognition of indigenous peoples, we began to look at what we were going to do.”

Without a doubt Subcomandante Moisés can, with pride, subscribe to his own words: “I think if you have to be a revolutionary you have to be one right until the end, because not reaching its consequences or abandoning people and those things, well it is not right. We the fighters, our other brothers from other states, from this same country Mexico and the world, we need to assume the responsibility….”. And he does.

Originally Published in Spanish by Desinformemonos

En español: http://desinformemonos.org/2013/02/moises-otro-subcomandante-en-el-ezln/

Translated by Nélida Montes de Oca

Editing: Chiapas Support Committee

Resumen de Noticias sobre los Zapatistas – Marzo de 2013

MARZO DE 2013 RESUMEN DE NOTICIAS SOBRE LOS ZAPATISTAS

En Chiapas

1. El EZLN concluye el ensayo ELLOS Y NOSOTROS – Durante el mes de febrero, el EZLN publicó las partes 5, 6 y 7 (la parte final) de ELLOS Y NOSOTROS. Las últimas tres partes, firmadas por Marcos, hablan de cómo las Juntas manejan el dinero, algunas experiencias en la resistencia, incluyendo comentarios críticos sobre Ciudades Rurales, el Proyecto Mesoamérica, antes llamado el Plan Puebla-Panamá, y el actual Plan para México. También revelan un poco de la historia de la organización fundadora (el FLN), revelando que varias clínicas de salud llevan los nombres de 2 compañeras del FLN quienes murieron en la lucha. En la parte 7, titulada “Dudas, sombras y un resumen en una palabra,” Marcos habla de las “sombras” que han hecho posible todo lo que han logrado. También habla de cómo asistir a las Escuelitas para borrar dudas sobre los zapatistas y el aprendizaje, y dice que el Sup Moisés enviará mas detalles sobre las escuelas.

2. Moisés publica fechas y otros detalles sobre las escuelitas – El 17 de marzo, el EZLN difundió un comunicado firmado por Subcomandante Moisés. Contiene mucha información sobre “las escuelitas” donde darán cursos sobre la Libertad Según los Zapatistas. Las escuelitas comenzarán inmediatamente después de la Celebración por el 10 Aniversario de las Juntas de Buen Gobierno (8 al 11 de agosto) y durarán una semana. Otros detalles contenidos en el comunicado incluye que las Juntas de Buen Gobierno por ahora se encuentran cerradas a brigadas, caravanas, entrevistas o cualquier visita que requiera del tiempo de las autoridades porque tod@s l@s zapatistas estarán ocupad@s preparando las escuelitas y los festejos. Los caracoles permanecerán abiertos a visitantes.

3. La corte suprema de México rechaza apelación de Patishtán – El 6 de marzo, la corte suprema rechazó otorgar una audiencia sobre “el reconocimiento de inocencia” a Alberto Patishtán, un maestro, defensor de derechos humanos y prisionero en Chiapas. Ha sido condenado a 60 años de prisión por emboscar y asesinar a 7 agentes de policía, la corte refirió la apelación a un tribunal en Chiapas. Fuentes legales en México piensan que hay pocas posibilidades de que la corte federal de distrito en Chiapas hará lo que la corte suprema negó hacer. Una campaña internacional por su liberación está en marcha.

4. La Suprema Corte Mexicana libera a otro indígena encarcelado por la matanza de Acteal – Una semana después de haber rechazado la revisión del caso del activista social Alberto Patishtán Gómez por su demanda de inocencia, la primera sala de la Suprema Corte anunció la liberación inmediata de Marcos Arias Pérez, quien habia sido acusado y encarcerlado con el cargo de haber participado en la matanza de Acteal el 22 diciembre de1997 (municipio Chenalhó, Chiapas). De nuevo, el argumento que se utilizó para su liberación fue que hubo violaciones de procedimiento en el desarrollo del proceso. El caso de Patishtán también cuenta con varias de tales violaciones, entónces ¿por qué continúa él en la prisión? Se dice que la influencia de algunos políticos de Chiapas son los de la culpa.

Por otras partes de México

1. Audiencia en la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos sobre violaciones en Atenco – Cuando el gobierno federal mexicano conjuntamente con el gobierno del estado de México condujeron una operación policiaca para aterrorizar, reprimir y torturar a los habitantes de San Salvador Atenco el 3 y 4 de Mayo de 2006, la policía incluyó la tortura sexual (violación forzada) en al menos 26 mujeres detenidas. El grupo de mujeres antepuso una demanda de investigación de su caso en la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, una división de la Organización de Estados Americanos con sede en Washington, DC. Finalmente, a mediados de este mes se celebró una audiencia sobre el caso. El gobierno ofreció una “disculpa por los excesos” y habló de una “solución amistosa” del caso, pero el grupo de mujeres víctimas de la agresión sexual rechazaron el ofrecimiento.

2. Corte mexicana anula inmunidad de Zedillo – El 6 de marzo, una corte mexicana emitió un fallo declarando que el ex-Presidente Ernesto Zedillo no era eligible para la protección de inmunidad bajo la Constitución Mexicana e invalidó la nota diplomática del entonces embajador mexicano en los EEUU que pedía al Departamento de Estado en ese país, recomendara inmunidad ante la corte federal de distrito en Connecticut en la cuál Zedillo ha sido demandado por algunas de las víctimas de la masacre de Acteal. La corte decidió que Zedillo ya no tenía derecho a la inmunidad porque ya no era presidente. Ahora vive en Connecticut e imparte clases en Yale. La demanda hecha en nombre de algunas de las víctimas de la masacre todavía sigue vigente en la corte federal de distrito en Connecticut.

3. Tráfico de Drogas, la quinta más grande fuente de empleos en México! – En un documento preparado por miembros de la Cámara de Diputados se estima que la actividad relacionada con el tráfico de drogas emplea alrededor de 468,000 personas, más que PEMEX (Petróleos Mexicanos, la compañía petrolera con más empleados en el mundo). El documento es parte de una propuesta de reforma legislativa que pretende crear una unidad técnica de inteligencia financiera que sea capaz de investigar y perseguir el lavado de dinero. El documento menciona que las ganancias por el tráfico de drogas se estiman entre 25 mil y 40 mil millónes de dólares anuales, y se reconoce que las estructuras del gobierno, incluyendo las policías, han sido infiltradas por la delincuencia organizada por medio de sobornos, chantajes y amenazas. El objetivo de la reforma es el de colocar diques al flujo del lavado de dinero que sirvan para reducir la capacidad de corrupción de esta actividad ilícita.

Compilación mensual hecha por el Comité de Apoyo a Chiapas: Nuestras principales fuentes de información son: La Jornada, Enlace Zapatista y el Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (Frayba).

An Interview With Gonzalo Ituarte on Maya Theology

The Church Weakened Its Social Leadership: Ituarte

** “Without the contributions of liberation theology, one cannot understand what happens today in the Vatican”

By: Blanche Petrich

Fray Gonzalo Ituarte Verduzco, provincial of the Dominican order in Mexico, assures that without the contributions liberation theology that was profiled in the 1960s and 70s –the era of the “red bishops” and persecution against the progressive clergy in Latin America– “one cannot understand what is happening today in the Vatican; one cannot understand Pope Francisco,” although the Argentine prelate comes from a current of conservative thought. He asserts this from a trajectory of almost three decades of construction of a different theology, at the side of don Samuel Ruiz, which placed the Diocese of San Cristóbal de las Casas team in confrontation with the Vatican.

The former Vicar of the diocese that transformed the profile of Chiapas in the last century, a participant in the failed peace negotiations between the federal government and the Zapatista National Liberation Army in San Andrés Larráinzar and the parish priest of Ocosingo, at the epicenter of the conflict, Ituarte Verduzco gives the benefit of the doubt to the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, now anointed as head of the Catholic Church, before the denunciations expressed about his complicity or silence in the face of the State terrorism that the Argentinian military dictatorship exercised.

–Yes, I give him the benefit of the doubt, because I give myself the same. I have lived an evolution; coming from a traditional Catholic family, with a very conservative view as student at the Latin American University. And because just like so many people in countries where there have been dictatorships, clerics had different capacities and lucidity in relation to the State and the context. The fact that Pope Francisco was not a militant opponent of the dictatorship does not necessarily make him an active accomplice. People go on changing, taking consciousness. Bergoglio was institutional and had the difficult papal role, with the obligation of protecting the Company of Jesus and the people with which he worked.

In the 90,s Ituarte lived in the headlights of the media, frequently as spokesperson for the bishop, as the port office for the denunciations and calls for attention from the communities of his diocese, since before the Zapatista Uprising until the failed dialogue in San Andrés (1995-1996). He was secretary of the National Mediation Commission (Conai, its initials in Spanish) and it fell to him, on the eve of the Acteal Massacre, to warn the deaf ears of the Chiapas government of the tragedy that was approaching (December 22, 1997). Since 2005, when he was elected the provincial for his congregation, that of the Preachers, he disappeared from the public scene. Now he returns to the arena and, in an interview, expresses optimism in the face of the change in the Vatican leadership.

Pope Francisco, seen from the rebel Church

–A Jesuit pope, Latin American, who opts for the name of Francisco as a signal for putting the vision of the poor at the center: how is he seen from the band of religious folks that, like you, lived the route of the option for the poor?

–Through the instinct of the hope that there is in Christianity we find very positive signs. We don’t want to be ingenious, because a structure like that of the Church, with its more than a billion affiliated and with all the factors that fall into it, does not change so quickly and radically. A person, although he may have a conservative formation from a doctrinal point of view, but with a beginning and a social practice like that of the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, indeed generates a different possibility. We hope that he attains it, with consistency, with perseverance, with spirit and solidarity.

–What elements, beyond the image and the gestures, seem hopeful in Pope Francisco?

–Since 200 years ago there has not been a pope that has opted for the priesthood not in a diocese but in a religious congregation. Besides, the Jesuits’ order has the logic of community life, close to the reality.

–How can he be different, because of having been a cardinal not diocesan?

–There is more feeling of itinerancy, of change, of advance, of the recognition of plurality, a broader vision of the Church, because the priests in congregations have more freedom and mobility by belonging to communities, not having properties, although sometimes we get trapped. But basically we take the oath of poverty to not be tied to our goods, our territory.

–With the new papacy, what’s going to happen with liberation theology?

–The debate about liberation theology passes to a second level, because it is also evolving. Liberation theology, as we live it, took the paradigm of the class struggle, the struggle for equality and justice as a central theme. We’re not going to have a Church like don Samuel’s again; that already passed. Today there is a contextual theology with a perspective from different environments and spaces. For example: feminist theology, theologies from the African, Latin American and Indian cultures and realities. The class struggle is no longer at the center.

But without liberation theology one cannot understand what is happening now in the Vatican, one cannot understand the current pope. Even with the incomprehension that did exist, the Church was touched by that era; it was enormously enriched.

Nevertheless, theology continues evolving. For example, today there is a new evaluation of cultures, which has permitted Indian theology to evolve. It is profoundly revolutionary that from the peoples of Central America and Mexico, basically the Maya culture, a theology is being developed from their cultures, not from Western ideology; that the ones who are writing this story are indigenous theologians. It is something very new, which is escaping the Western paradigms. Faith is visualized from the Indian cosmovision, with its myths, rituals and traditions. And dimensions continue appearing that are not going to have the name liberation theology, but that come from there and are profoundly liberating.

–Where, concretely, is this being generated?

–Chiapas, definitely, Guatemala, El Salvador, Yucatán. They meet systematically, do a review of their own tradition, of the old Maya testament contrasted with Western tradition and are seeing the different dimensions. That gives them a re-affirmation to dialogue as equals. And the women’s perspective: there are very lucid theologies that are opening paths for liberation. And the theology of migration: the Bible is the book of migrations; it is the fruit of many cultures that interact and Enright each other.

Saving an enormous distance

–The Church’s base communities, the liberation theologians, the religious people that were active in the option for the poor always paddled against the current of dominant ideas in Rome. The distance has been abysmal. How can one be saved now?

–It is difficult for a person that lives in an intellectual world, so far from the reality of the Latin American poor, as the high spheres are in Rome, to understand what was gestating and developing there below. The problem is that the Church transferred so much power to the papacy that it weakened the leadership of the social church, the diocese and the local pastors.

–Are there clear signs of that about which you speak –Bible, liberating theology or whatever it may be called in the future, commitment– is the new pope interested or will we have to point it out to him?

–The fact that he has been in close proximity with the poor makes me hope that it is indeed on his horizon. Argentina, with its crisis, with the recent struggles, including the confrontation that he has had with the current government, indicates that these themes are indeed present and he will have to address them. And we must help him.

———————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Saturday, April 6, 2013

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2013/04/06/sociedad/040n1soc

Zapatista News Summary – March 2013

MARCH 2013 ZAPATISTA NEWS SUMMARY

In Chiapas

1. EZLN Concludes THEM AND US Essay – During February, the EZLN released Parts 5, 6 and 7 (the final part) of THEM AND US. All 7 parts are translated into English on our blog: https://compamanuel.wordpress.com/ The last three parts, signed by Marcos, talk about how money is handled by the Juntas, some experiences in resistance, including critical comments about Rural Cities, the Mesoamerica Project, formerly the Plan Puebla-Panamá and the current Plan for Mexico. They also revealed a little history of their founding organization (the FLN) by revealing that several clinics are named for 2 FLN compañeras who died in the struggle. In Part 7, entitled Doubts, Shadows and one word, Marcos talks about the “shadows” that have made what they have done possible. He also talks about coming to the Little Schools to erase your doubts about the Zapatistas and learning and says that Sup Moisés will send out details about those schools.

2. Moisés Issues Dates and Other Details About the “Little Schools” – On March 17, the EZLN issued a communiqué signed by Subcomandante Moisés. It contains much of the information about the “escuelitas” or little schools” where they will teach Freedom According to the Zapatistas. For details, see: https://compamanuel.wordpress.com/2013/03/20/ezln-moises-dates-and-other-details-for-the-little-zapatista-school/ The Little Schools will begin immediately following the Celebration for the 10th Anniversary of the Good Government Juntas (August 8 to 11) and will last for one (1) week. Another of the details contained in the communiqué is that the Good Government Juntas are now closed to brigades, caravans, interviews or any visit that requires the time of the authorities because all the Zapatistas will be busy preparing for the little schools and the celebrations. The Caracoles remain open to visitors.

3. Mexico’s Supreme Court Denies Patishtán’s Appeal – On March 6, Mexico’s Supreme Court refused to grant a “recognitions of innocence” hearing to Alberto Patishtán, a teacher, human rights defender and prisoner in Chiapas. Sentenced to 60 years in prison for the ambush and murder of 7 police, the Court referred the appeal to a collegiate tribunal in Chiapas. Legal sources in Mexico think the chances are slim that a federal court in Chiapas will do what the Supreme Court refused to do. An international campaign in support of his freedom is underway.

4. Mexico’s Supreme Court Releases Another Man Convicted in the Acteal Massacre Case – One week after it refused to hear the request from the social struggler Alberto Patishtán Gómez for a recognition of innocence, the first hall of the Supreme Court resolved the immediate liberation of Marcos Arias Pérez, accused (and convicted) of participating in the Acteal Massacre on December 22, 1997 in the municipality of Chenalhó, Chiapas. Once again, the rationale for the release was because of due process violations. Patishtán’s case is also replete with due process violations, so what is prohibiting Patishtán’s release? Speculation is mounting that influential politicians in Chiapas may be to blame.

In Other Parts of Mexico

1. Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Holds Hearing on Atenco Rapes – When the Mexican governments and the state government of Mexico jointly conducted a police operation to terrorize, repress and torture the population of San Salvador Atenco on May 3 and 4, 2006, the police included sexual torture (forced rape) on at least 26 women in custody. They filed a complaint with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, a division of the Organization of American States, with headquarters in Washington, DC. A hearing was finally held in the middle of the month. The government offered an apology and a friendly resolution, but the women who suffered the sexual assaults rejected the offer.

2. Mexican Court Annuls Immunity for Zedillo – On March 6, a Mexican Court ruled that former president Ernest Zedillo was not eligible for immunity protection under the Mexican Constitution and invalidated a diplomatic note from the then Mexican Ambassador to the United States requesting that the US State Department recommend immunity to the Connecticut federal district court in which Zedillo has been sued by some victims of the Acteal Massacre. The court reasoned that Zedillo was no longer entitled to immunity because he was no longer president. He now lives in Connecticut and teaches at Yale. The lawsuit filed on behalf of some of the victims of the massacre is still an open case in the Connecticut court. For the full story: http://yaledailynews.com/blog/2013/03/25/mexican-court-rules-zedillo-ineligible-for-immunity/

3. Drug Trafficking Is 5th Largest Source of Jobs in Mexico! – A report prepared for members of Mexico’s Chamber of Deputies state that estimates are that drug trafficking employs around 468,000 people, more that PEMEX (the acronym for Petroleos Mexicanos), the oil company with the most employees in the world). The purpose of the report is to support a proposed legislative change to create a financial intelligence technical unit capable of investigating and pursuing money laundering. The report cites estimates of profits from drug trafficking at somewhere between $25 and 40 billion dollars per year and concedes that governmental structures, including police, are infiltrated with drug trafficking employees and corrupted with bribes, blackmail and threats. The conclusion seems to be that there is no way to stop the corrupting influence of that kind of money without putting dams in the way of money laundering.

___________________________________

Compiled monthly by the Chiapas Support Committee.The primary sources for our information are: La Jornada, Enlace Zapatista and the Fray Bartolome de las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba).

Raúl Zibechi: Can the State Be the Commons?

Can the State Be the Commons?

By: Raúl Zibechi

Rigorous and committed reflections and analyses are essential in this turbulent and chaotic period, in which the anti-systemic forces have difficulties orienting themselves and defining a direction. Some of those analyses have played an outstanding role in the debates that the movements carry out, because they illuminate the themes most important for being oriented in the long run.

The works of the geographer David Harvey, in particular those that permit comprehending better the modes of capital accumulation, have been incorporated by numerous movements for analyzing the reality that they wish to transform. The concept of “accumulation by dispossession,” formulated in his book The New Imperialism (Akal, 2004), is one of the force-ideas accepted by those who belong to anti-systemic organizations.

In other works Harvey persists in comprehending in more depth the movements of capital and its imprint on geographical spaces and territories, emphasizing how they have reconfigured the urban scheme in recent decades. In The Enigma of Capital and the Crisis of Capitalism (Akal, 2012), he established the strict relationship between urbanization, capital accumulation capital and sudden appearance of crisis. Since the postwar (1945), he points out; suburbanization played an important role in the absorption of surplus capital and labor.

Consumption explains 70 percent of the US la economy (compared to the 20 percent that it represented in the 19th Century), which leads him to conclude that: “the organization of consumption through urbanization has been converted into something absolutely decisive for the dynamic of capitalism” (p. 147). Consequent with his previous works, he puts the creation of new spaces and territories in a central place, and considers them the fundamental aspect of the reproduction of capitalism, emphasizing the categories of “rental of land” and “price of land” as the hinges between capital and geography.

The analysis of the “territorial logic” of capitalism, complementary and convergent with the flows of capital that cross spaces with “a logic more systematic and molecular than territorial” (p. 171), leads Harvey to approach power, states and the resistances, remembering that in this period: “the State ands capital are more strictly interwoven than ever” (p. 182). Here he enters into a much more delicate terrain. Although he may seem contradictory with that assertion, he defends “the utilization of the State as the principal instrument of counter-power in the face of capital” (p. 173).

Anyhow, Harvey recognizes the Zapatista Good Government Juntas as territorial organizations capable of creating a new social order. At this point he does not establish any difference between territorial and State organization, or between instituted power and counter-powers. Although he does not work in that direction, the debate about whether all territorial power is synonymous with State remains open and we have still not advanced much in that respect.

I don’t believe that it’s most appropriate to continue a debate of an ideological character about the State –although we know Marx’s position on that, he always held to the need for destroying the State apparatus–, without previously bringing up the paths for leaving capitalism and traveling towards a different world. In his most recent work, Rebel cities, Harvey dedicates a chapter to “The creation of urban communes,” where he criticizes frontally the centralized organization of Leninist inspiration as “horizontalism,” which he accuses of centering on practices of small groups that turn out to be impossible on larger scales and on a global scale.

Harvey also questions the “local autonomies” as spaces adequate for protecting the common good, because in fact “they demand some kind of approach” (enclosure, p. 71). Harvey’s reasoning is anchored in the “scales”: having a community garden in your barrio is something good, he says, but to resolve global warming, water and air quality or problems on a global scale, we cannot appeal to assemblies or to the forms of organization that the movements have today. For that there is no other path than appealing to the State, on a national, regional or municipal scale.

There are three considerations in that regard. What Harvey proposes is inscribed in a profound historic tendency that has regained vigor in recent years. Although the writer does not share it, the bulk of the Latin American movements migrated from autonomous positions to statist and electoral practices. To not recognize this tendency does not contribute to deepening the debates.

The second has to do with the character of the State: can the State, which is not the commons but rather the expression of a social class, have any usefulness for protecting the commons? The community, the true expression of the commons, is the human organization most adequate for protecting the common wealth. It is not accidental that there where that wealth has been preserved is where communitarian ways predominate in their most diverse forms.

In third place, it is necessary to undo a misunderstanding that has earned enormous esteem in recent years: assuming the administration of the State, the government, became for many activists the path for traveling toward a new world. Beyond how the efforts of the progressive governments are evaluated, there does not exist anywhere in the world any experience with construction of new social relations from the State inherited by capitalism.

“The working class cannot be limited simply to taking possession of the State machine such as it is and using it for its own purposes,” Marx wrote in 1872, upon making of the Paris Commune. That we still don’t have the material force to do what Marx recommended is not saying that our horizon ought to limit itself to struggling by administering what exists, because we will never overcome capitalism that way.

—————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Friday, March 22, 2013

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2013/03/22/opinion/031a1pol

English translation: Chiapas Support Committee

EZLN: Moises: Dates and Other Details for the Little Zapatista School

Dates and Other Details for the Little Zapatista School

ZAPATISTA NATIONAL LIBERATION ARMY

MEXICO

March 2013.

Compañeras and compañeros, brothers and sisters of the Sixth:

Regarding visits, caravans, and projects.

As you all know, we are preparing our classes for the little schools; that is what we will be focusing on for now so that they turn out well and make for good students.

And we, together with the [autonomous] authorities, think that there are things that we will not be able to attend to so as not to distract ourselves from this task, for example: agreeing to do interviews, or exchanging experiences, or receiving caravans, or work teams, or discussing ideas for a project. So please don’t make a trip here for nothing, because neither the Good Government Junta or the autonomous authorities, or the project commissions will be able to attend to you in these matters.

If a person, group, or collective is thinking of bringing a caravan with some kind of support for the communities, we ask you to please wait for the appropriate time, or if you have already arranged the trip, then please leave whatever you bring in CIDECI, with Doctor Raymundo, in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico.

We aren’t saying that caravans of support can never come, but they CAN’T come now, because we want to focus on the little school. We want to let you know this, so that you don’t misunderstand why you are not attended to.

We want to let you know this so that you don’t plan trips that require conversations with our authorities; we won’t be able to attend to you for the simple reason that all of our efforts will go toward our little school, which is for you, for Mexico and the world, and that is why we are directing all our efforts there.

So while we will be in the Juntas de Buen Gobierno of the 5 caracoles; we won’t be able to attend to you, but you can visit the caracoles.

The same goes for ongoing projects in the 5 Juntas, there are things that we won’t be able to attend to, we can only do what is within our ability and which does not require consultations or a lot of movement for our people. If something does require these things, it will be tended to at another time.

We want you to understand us; for us, it is not the time for caravans, projects, interviews, exchanges of experiences, or other things. For us Zapatistas (women and men), it is time to prepare for the little school. We WON’T have time for other things, unless the bad government wants to really mess with us and then yes, that would change things.

We believe that you, compañeras and compañeros, brothers and sisters, understand.

Regarding the School

Here we will give you the first details about the little school, so that those of you who will take classes can begin to make preparations.

1. Everyone who feels called is invited to the fiesta of the Caracoles. The fiesta will be in all 5 caracoles, so you can go to whichever you want. The arrival date will be August 8th, the fiesta will be on the 9th and 10th, and the return date will be the 11th. Note: The fiesta to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Caracoles is not the same thing as the little school. Don’t confuse them.

2. With this fiesta, the Zapatista bases of support celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Juntas de Buen Gobierno, but not only that.

3. These days will be the beginning of our little school, which is very other, where our bosses—that is to say, the Zapatista bases of support—will give classes on their thought and action on liberty according to Zapatismo: their successes, their failures, their problems, their solutions, the things which have moved forward, the things that have gotten bogged down, and the things that are missing, because what is missing is yet to come.

4. The first course (we will have many, depending on when those who attend are able), of the first level is 7 days long, including the arrival and departure time. The arrival date will be August 11th, the class begins on August 12th, 2013 and ends on August 16th, 2013. And the departure date will be August 17th, 2013. Those who finish the course and would like to stay longer can visit the other caracoles outside of where they had their course. The course is the same in all of the caracoles, but people can visit caracoles different from the one they were assigned, but at that point they will be on their own.

5. Little by little, we will explain how registration works for the little school of liberty according to the Zapatistas, but we will let you know now that it is laic and free of cost. The pre-registration will be with the Support Teams of the Sixth Commission, national and international, on the Enlace Zapatista web page, and by email. Students will then register at CIDECI, in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas. We will begin sending the invitations, according to our capacities, as of March 18, 2013.

6. The school is not open to anyone who wants to come; rather, we will invite people directly. We will take care of these compas who we invite, we will give them food, a place to sleep that is clean and satisfactory, and we will give each of them a guardian (or guardiana), their own “Votán,”[i] who will make sure that they are well and that they don’t suffer too much in the class, only a little, but always, yes, some.

7. The students will need to study very hard. The first level has 4 themes: Autonomous Government I, Autonomous Government II, Participation of Women in Autonomous Government, and Resistance. Each theme has its own textbook. The textbooks have between 60 and 80 pages each, and the parts that SupMarcos already gave you to look at are only a tiny part of each book (3 or 4 pages). Each textbook costs 20 pesos, which is what we calculated as the cost of production.

8. This first level of the course lasts for 7 days and/or however much time a compa has available, because we know people have their work, their family, their struggle, their commitments, that is to say, their own calendar and geography.

9. The first course is only first grade, there is still much more to come, meaning that the school isn’t finished quickly; it will take a long time. Whoever passes the first level can go on to the second one.

10. Regarding costs: each compa has to cover their own costs to get to CIDECI, in San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, and to get back to their corner of the world. From CIDECI they will go to the little school to which they are assigned and when they finish, they will return to CIDECI and from there each one will go home. In the school, which is in the village, they won’t want for anything; it may be beans, rice, or vegetables, but their table will not be lacking. There the Zapatistas will cover the costs for each student. Each student will live with an indigenous Zapatista family. During the days that they are in school this will be the student’s family. They will eat, work, rest, sing, and dance with this family, who will also walk them to their assigned school, to the education center. And the “Votán,” the guardian or guardiana, will always accompany them. That is, we will watch out for each student. If they get sick we will cure them, or if it is serious we will take them to a hospital. But whatever is in their head when they arrive and when they leave, well, we can’t do anything about that; what each compañero or compañera does with what they see, hear, or learn, is their responsibility. That is, we will teach them the theory; the practice they will see about themselves in their own corner of the world.

11. The costs of the school we will figure out ourselves. Maybe we’ll have a festival of music and dancing, or some paintings or artisanal goods, but don’t worry, because we will find a way and in any case, there are always good people who support good things. For those who would like to make a donation to the school, we will leave a jar in the student registration area at CIDECI, with the compas from the University of the Earth, in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas. Whoever wants to donate some money can put it in the jar, no one will know who gave money or how much they gave; this way those who gave a lot won’t think too much of themselves and those who gave a little won’t feel sad. We will not allow gifts of money or other things to be given in the schools, Caracoles, or families to which you are assigned. This is to avoid an unfair situation where some people receive things and others do not. Whatever people would like to donate should be left at CIDECI, with the compas from the University of the Earth, in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. They will collect it all and then we will divide it evenly among everyone later, that is, if there is anything. If not, it doesn’t matter; what matters is you.

12. There are other ways of taking the course at the little Zapatista school. We are going to ask for support from the compas of the free, independent, libertarian, and autonomous media, and from those who know about this thing called videoconferencing. Because we know that many people will not be able to come because of work issues, or personal issues, or family. We also know that there are people who don’t understand Spanish but do want to learn how the Zapatistas have done what they have done and undone what they have undone. So we are going to have a special course that one can take via video camera wherever there is a group of willing students who are ready with their textbooks, and that way, over internet, they will be able to see the course and ask questions of the teachers—the Zapatista bases of support. In order to plan this, we will invite some alternative media to a special meeting in order to come to an agreement on how to do the videoconferences and also so that they can photograph and videotape the places that we will talk about in the classes, so that everyone can verify if what the professors (men and women) say is true or not.

Another form by which people can take the class is with the DVDs we will make of the course, for those who can’t go anywhere and can only study in their house, so that they can also learn.

13. In order to attend the little Zapatista school, you will have to take a preparatory course where the life of the Zapatista communities and their internal rules will be explained, so that you don’t commit any infractions. And also so you know what you need to bring. For example, you shouldn’t bring those things called “tents” that aren’t good for anything anyway; we are going to provide you accommodations with indigenous Zapatista families.

14. Once and for all we want to make it clear that the production, commercialization, exchange, and consumption of any kind of drugs or alcohol is PROHIBITED. The carrying or use of any kind of weapon, loaded or unloaded, is also prohibited. Whoever asks to join the EZLN or anything militarily related will be expelled. We are not recruiting nor promoting armed struggle, but rather organization and autonomy for liberty. Any kind of propaganda, political or religious, is also prohibited.

15. There is no age limit to attend the little school; but any minors should come with an adult who is responsible for them.

16. When you register, after having been invited, we ask you to clarify if you are a man, woman, or other, in order to accommodate you, as every one is an individual (individuo, individua, or individuoa)[ii] and will be respected and cared for. Here we do not discriminate against anyone on the basis of gender, sexual preference, race, creed, or nationality. Any act of discrimination will be punished with expulsion.

17. If anyone has a chronic illness, we ask you to bring your medicine and let us know about it when you register so that we can keep an eye out for you.

18. When you register, after being invited, we ask that you make clear your age and health condition so that we can accommodate you in one of the schools where you won’t suffer more than necessary.

19. If you are invited and you can’t attend at this first date, don’t worry. Just let us know when you can attend and we will do the course for you when you can come. Also, if someone can’t finish the whole course or can’t come after having registered, no problem, you can finish or make it up later. Remember though you can also attend the videoconferences that will be given outside Zapatista territory.

20. In other writings I will continue explaining more things and clearing up any doubts you might have. But what I have said here are the basics.

That’s all for now.

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast,

Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés.

Rector of the Little Zapatista School

Mexico, March 2013.

P.S. I put SupMarcos in charge of adding some videos to this text that relate to our little school.

__________________________

Originally Published in Spanish by Enlace Zapatista

En español: http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/03/17/fechas-y-otras-cosas-para-la-escuelita-zapatista/

Francisco Gabilondo Soler, Cri Cri, with a track that is now a classic: “Caminito de la escuela” (The Path to School).

————————————————————————————-

The Little Squirrels of Lalo Guerrero with “Vamos a la escuela” (Let’s go to school) and Pánfilo’s excuses not to go to school.

————————————————————————————-

School squabbles to the rhythm of ska, with Tremenda Korte and this track “Por Nefasto”.

[i] In the lexicon of the EZLN, Votán is usually used in reference to the legendary Votán – Zapata, in which the spirit of Zapata lives as “the guardian and heart of the people.” See “Closing Speech to The National Indigenous Forum,” EZLN, January 9, 1996.

[ii] The EZLN often uses the suffix –oa (individuoa, compañeroa) to provide a noun form that is not strictly feminine or masculine.

Zapantera Negra: Zapatista Black Panther Art

ZAPANTERAS NEGRAS: Zapatista Black Panther Art in S.F.

April 10, 2013 @ 7:00pm at Rincon 3265 17th St. #204

(Between Mission and Capp) San Francisco CA 94110

In 2012, Emory Douglas, former Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, went to Chiapas to work with Zapatista artists to make art, share visions, bringing together the revolutionary art traditions of two communities.

On April 10, artists Emory Douglas and Rigo 23 will present art and photography from the Zapantera Negra art project and share their experiences with the Panthers and the Zapatistas.

Join the Chiapas Support Committee on April 10 to celebrate the life and

vision of Emiliano Zapata through the art work of two communities

whose hearts and movements lead a struggle for a boundless liberation.

* *** *

All proceeds support Zapatista communities

$5.00-20.00 donation No one turned away for lack of funds

* *** *

For more information contact the Chiapas Support Committee

(510) 654-9587 cezmat@igc.org

* *** *

Chiapas Support Committee/Comité de Apoyo a Chiapas

P.O. Box 3421, Oakland, CA 94609

Tel: (510) 654-9587

Email: cezmat@igc.org

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Chiapas-Support-Committee-Oakland/86234490686

Marcos: THEM AND US VII – The Smallest Ones – 7. Doubts and Shadows

The Smallest Ones, 7th and Final Part

7. On Doubts, Shadows, and A One-Word Summary

March 2013

Doubts

If after reading the excerpts from the compañeras and compañeros of the EZLN you still think that the indigenous members of the Zapatistas are manipulated by the perverted mind of Supmarcos (and now by Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés) and that nothing has changed in Zapatista territory since 1994, then there’s no hope for you.

I wouldn’t recommend that you turn the television off or that you stop regurgitating the circular arguments that tend to be circulated by the intellectuals and their followers, because if you did so your mind would be empty. Go ahead and keep thinking about how the recent telecommunications law will democratize information, that it will increase the quality of programming, and that it will make cell phone service better.

But if you thought this way, you would never have made it to this part of “Them and Us,” so let’s just take it as a hypothetical that you are a person with an average IQ and immersed in progressive culture. With these characteristics, it is very probable that you practice constant doubt in the face of just about everything, so it’s only logical to assume that you doubt what you have read here in the previous pages. To doubt is not something that should be condemned, it is one of the healthiest (and most forgotten) intellectual exercises available to humanity—especially if it is exercised with respect to a movement like the Zapatista or neo-Zapatista movements, about which so many things have been said (the majority of which do not even come close to what we are).

Let’s leave to one side the fact that it was undeniable even to the mainstream press that tens of thousands of indigenous Zapatistas simultaneously took 5 municipal seats in the Southeast states of Chiapas [a reference to the events of December 21, 2012].

Let’s leave that aside and deal head on with doubts: if nothing has changed in the Zapatista indigenous communities, why have they grown? Weren’t they saying that the EZLN was history? That the ezln’s errors (okay, okay, Marcos’ errors) had come at the cost of their existence (their “media” existence, but they never mentioned that part)? Wasn’t the Zapatista leadership disbanded? Hadn’t the EZLN disappeared and all that remained of them was the vague memories of those outside of Chiapas who feel and know that struggle isn’t something that can be subject to the comings and goings of fads?

Ok, let’s ignore this fact (that the EZLN grew exponentially during these times when they had fallen out of fashion) and abandon any attempt to raise these concerns (concerns that will only lead to the editing of your comments on articles in the national newspapers or your banning from these sites, “for ever more”).

Lets return to methodical doubt:

What if the words that appeared in the previous pages that were supposedly from indigenous Zapatistas (men and women) were actually written by Marcos?

That is, what if Marcos just simulated that others were the ones that wrote and felt those words?

What if the autonomous schools don’t actually exist?

What if….the hospitals and the clinics, and the accountability process, and the indigenous women in leadership positions, and the productive lands, and the Zapatista air force, and…..?

Seriously, what if none of the things that those indigenous people talk about exist, what if those indigenous people don’t exist?

In sum, what if everything is just a monumental lie created by Marcos (and Moíses since that’s the process we’ve now begun) in order to console those leftists (don’t ever forget that they’re dirty, ugly, bad, irreverent) who are always present and who are always just a few, very few, a tiny minority, with mere illusion? What if the Supmarcos made all that stuff up?

Wouldn’t it be good to place your doubts side by side with reality?

What if it was possible for you to see for yourself those schools, the clinics, the hospitals, those projects, those women and men?

What if you could listen directly to those Mexican, indigenous, Zapatista men and women, making an effort to speak in Spanish so that they could explain, so that they could tell you their history, not to try to convince or recruit you, but just so that you could understand that the world is very big and it has many worlds inside itself?

What if you could concentrate on observing and listening, without talking, without giving your opinion?

Would you take up that challenge? Or would you continue taking refuge in your cynicism, that solid and wonderful castle of reasons not to do anything?

Would you ask to be invited? Would you accept that invitation?

Would you come to a little school in which the professors (women and men) are indigenous and whose mother tongue is considered a mere “dialect”?

Would you be able to contain your desire to study them as if they were anthropological, psychological, legal, esoteric, or historiographic objects? Would you hold back your desire to interview them? To tell them your opinion? To give them your advice? To give them orders?

Would you look at them? That is, would you listen to them?

-*-

Shadows.

On one side of this light that now shines you can’t see the form of the strangely shaped shadows that have made it all possible. Because another of the paradoxes that characterize Zapatismo is that it is not light that creates the shadows, rather, it is from these shadows that light is born.

Women and men from corners near and far across the planet made possible what we will show you, but they also enriched, with their gaze, the path of these indigenous Zapatista men and women who today once again raise the banner of a dignified life.

Individuals (women and men), groups, collectives, all types of organizations, and at all different levels, contributed so that this small step of the very smallest could be taken.

From all five continents arrived gazes that, from below and to the left, offered their respect and support. And with this respect and support not only schools and hospitals were built, but we also the indigenous Zapatista heart that, through those gazes, through those windows, were able to look out to all of the corners of the world.

If there is a cosmopolitan place on Mexican lands it is certainly Zapatista territory.

In the face of all this support nothing but an effort of equal magnitude would have sufficed.

I think, we think, that all those people from Mexico and the world can and should share in this small joy that today walks through the mountains of Southeastern Mexico and has an indigenous face.

We know, I know, that you are not expecting, that you are not asking for, that you do not demand this great embrace that we send you. But this is the way that the Zapatistas (men and women) thank our companer@s (and we especially thank those who knew how to be nobody). Perhaps without intending to, you were and are for us (women and men) the best school. And it goes without saying that we will not spare any effort to assure that, regardless of your calendars and geographies, you will always respond affirmatively to the question of whether it was worth it.

To all (women) (I apologize from the depths of my sexist essence, but women are a majority both quantitatively and qualitatively) and to all (men): thank you.

(….)

And, well, there are shadows and then there are shadows.

The most anonymous and imperceptible [of these shadows] are some short-statured women and men whose skin is the color of the earth. They left behind everything that they had, even if it wasn’t much, and they became warriors (women and men). In silence, in darkness, they contributed and continue to contribute, like no one else, so that all of this could be possible.

And now I am referring to the insurgents (women and men), my compañer@s.

They come and go, they live, they struggle and die in silence, without making any fuss, and without anyone, besides ourselves, noticing them. They have no face and no life to themselves. Their names, their stories. may only come to mind after many calendars have come and gone. Maybe then around a fire, while the coffee is boiling in an old pewter teapot and the fire of the word has been ignited, someone or something will toast to their memory.

Regardless, it won’t matter much because what this has been about, what it is about, what it has always been about, is to contribute in some way to build those words with which the Zapatista stories, anecdotes, and histories, real and imaginary, begin. Just like how what is today a reality began, that is, with a:

“There Will Be a Time…”

Vale. Health, and let there always be listening and the gaze.

(this will not continue)

In name of the women, men, children, elderly, insurgents (men and women) of

The Zapatista Army for National Liberation.

From the Mountains of Southeastern Mexico.

Subcomandante Insurgent Marcos.

Mexico, March 2013.

An Anticipatory P.S.: There will be more writings, don’t get happy ahead of yourselves. They will be primarily from Subcomandante Insurgent Moisés regarding the little school: the dates, the places, the invitations, the sign-up, the propaedeutics (preparatory studies), the rules, the grade levels, the uniforms, the school supplies, the grades, the extra help, where you can find the exams with all the answers etc… But if you ask us how many grade levels there are [in our little school] and how much time it will take until graduation, we will answer: we (women and men) have been here for more than 500 years and we are still learning.

P.S. That Gives Some Advice Regarding Attendance at the Little School: Eduardo Galeano, a sage in that difficult art of observing and listening, wrote the following in his book, “ The Children of the Days,” on the March calendar:

“Carlos and Gudrun Lenkersdorf were born and had lived in Germany. In 1973 these illustrious professors arrived in Mexico. They entered the Mayan world, a Tojolabal community, and they introduced themselves with the following words:

‘We came to learn.’

The indigenous people were silent. Later someone would explain the silence:

‘This is the first time that someone has said that to us.’

Learning, they stayed there for years and years.

From the indigenous languages they learned that there is no hierarchy that separates the object from the subject, because I drink the water that drinks me and I am observed by everything I observe, and they learned how to greet people in the following way:

‘I am another you.’

‘You are another me.’ “

Take heed of Don Galeano, because it is only by knowing how to observe and listen that one learns.

P.S. That Explains Something About Calendars and Geographies: Our dead say that we have to know how to observe and listen to everything, but that in the south there will always be a special richness. As you may have noticed from watching the videos (there are many videos still left over, perhaps for another time) that accompanied the communiqués in this “Them and Us” series, we tried to thread together many calendars and geographies, but we dug into our much respected southern region of Latin America. This was not only because of Argentina and Uruguay, lands wise to rebellion, but also due to the fact that according to us (women and men), there exists in the Mapuche people not only pain and rage, but also an impeccable integrity in the struggle and a profound sagacity for those who know how to observe and listen. If there is a corner of the world toward which bridges must be built, it is Mapuche territory. It is thanks to those people and to all the disappeared and all the imprisoned of this pained continent that our memory still lives. I’m not sure about the other side of these words, but I know that from this side of these words, “Neither forgive nor forget!”

A Synthetic P.S.: Yes, we know that this challenge has not been and will not be easy. Great threats and blows of all types will come from all directions. That is how our path has been and will be. Terrible and marvelous things make up our history. It will continue to be this way. But if you were to ask us how we would summarize all of this in one word: the pain, the sleepless nights, the deaths that hurt us, the sacrifices, the continual effort to swim against the tide, the loneliness, the absences, the persecution, and, above all, the stubborn memory of those who came before us and are no longer here, it would be something that unites all the colors that exist below and to the left no matter what their calendar or geography. More than a word, it is a cry:

Liberty…………Liberty!……………LIBERTY!

Vale de Nuez.

The Sup putting away his computer and walking, always walking.

——————————————————————————

A poem by Mario Benedetti (which responds to the question of why, despite everything, we sing), put to music by Alberto Favero. Here performed by Silvana Garre, Juan Carlos Baglietto, Nito Mestre. ¡Ni perdón ni olvido!

——————————————————————————

Camila Moreno performs “De la tierra,” dedicated to the Mapuche warrior of struggle, Jaime Mendoza Collio, shot in the back by police.

——————————————————————————

Mercedes Sosa, ours, everyone’s, of all times, singing Rafael Amor’s “Corazón Libre.” The message is terrible and wonderful: never give up.

—————————————————————————