Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Confrontation in Chiapas leaves one dead

AUTHORITIES and TEACHERS ACCUSE EACH OTHER of PROVOKING TEACHER’S DEATH

This is an image published in a video in which hundreds of members of the security forces and dissident teachers maintain positions in Ocozocoautla, adjacent to Tuxtla Gutiérrez, at a crossroad that leads to the site of the teachers evaluation examination. To the left is the bus that allegedly ran over 3 teachers and was set on fire. Towards the center (with arrow pointing) is the body of the dead teacher.

By: Elio Henríquez, Correspondent

San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas

One teacher dead, six detained and five injured (three of them police) is the result of a confrontation that occurred between security forces and teachers of Sections 7 and 40 of the National Education Workers Union (SNTE, its initials in Spanish), when they attempted to boycott the teacher evaluation, the State’s Attorney General of Justice (PGJE) reported.

Education authorities originally announced that the exam would be held on the 12th and 13th of this month, but at the last minute decided to move it up to start on Tuesday, December 8; therefore, the teachers initiated mobilizations to attempt impeding their application.

The confrontation occurred at the crossroad that leads to the School National of Civil Protection –site of the exam–, in the municipality of Ocozocoautla, which is adjacent to Tuxtla Gutiérrez.

The PGJE asserted that the demonstrators tool possession of a bus that they set in motion for the purpose of running over a group of police, but upon carrying out the maneuver rolled over three of their compañeros, among them David Gemayel Ruiz Estudillo, a teacher from Section 40, who died.

On the other hand, Hugo Alvarado Domínguez, spokesperson for Section 7, explained that the teacher was run over by a police bus when they (the police) were attacking them (the teachers) “in a brutal and inhumane manner.” At the first barrier to contain the teachers, he explained, agents of the National Gendarmerie participated, and at the second, members of the Army.

Members of the police were “between 10,000 and 15,000, we were also thousands, but they were armed,” he emphasized.

Alvarado Domínguez detailed that during the confrontation three teachers, two normalistas and one father were detained

He commented that during the early morning hours the teachers detained some buses that were allegedly transporting teachers for presenting the evaluation, but in reality they were administrative workers of the very same federalized assistant secretary of Education.

Pedro Gómez Bahamaca, Secretary of jobs and primary level conflicts and part of the leadership of the SNTE’s Section 7, said: “They gassed us and attacked us, and we didn’t realize at that time that infiltrators took possession of the bus and therefore we are not able to accept the responsibility that they are pointing at us.” He demanded the liberation of the six detained.

The PGJE stated, about the deceased teacher that: “experts performed investigative work at the scene of the incident, among which they emphasize the lifting up of the cadaver and forensic genetics that permitted corroborating that the rear tires on the right side of the bus had traces of blood that corresponds to Ruiz Estudillo.”

He asserted that: “the position of the body and the drag of the AEXA line’s vehicle with license plates 664-HU-2, which stayed on the edge of the incident, also coincide.”

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Published in English by Compañero Manuel

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

Zibechi: The storms that are coming

General view of where a dam burst in the Brazilian village of Bento Rodriguez in Mariana, Minas Gerais state, Nov. 6, 2015. Photo: Douglas Magno/AFP/Getty Images

By: Raúl Zibechi

The end of the progressive cycle implies the dissolution of hegemonies and the beginning of a period of dominations, of greater repression against the organized popular sectors. Until now we have been commenting on the causes of the end of the cycle; now it’s necessary to start to comprehend the consequences, tremendous, unattractive, demolishing in many cases.

The recent election of Mauricio Macri as president of Argentina is a turn to the right that calls to light the flame of social conflict. The response of the editors of the conservative daily newspaper La Nación with an editorial that openly defends State terrorism is a sample of what’s coming, but also of the resistances that will have to confront the project of the traditional right.

We are not facing a return to the 1990s, neoliberal and privatizing, because those below are in a different situation, more organized, with greater self esteem and understanding of the model that they suffer and, above all, with greater ability for confronting the powerful. Collective experiences don’t happen in vain, they leave deep impressions, wisdoms and ways of doing things that in this new stage will play a decisive role in the necessary resistance to the new rights.

The period that is opening in the whole South American region, where President Rafael Correa already announced that he does not aspire to re-election, will be one of greater economic, social and political instability; of increasing interference of the Pentagon’s militarism; of new difficulties for regional integration, which already crosses through serious difficulties; of the deterioration of the living conditions of the popular sectors, whose incomes started to erode in the last two years.

In this new climate, I find some questions central:

The first is that there will not be political forces capable of governing with a minimal consensus, like the one that the progressive governments had obtained in their first stage. There will not be consensus in governments like those of Macri; but it’s convenient to remember that the Lula hegemony broke under the second mandate of Dilma Rousseff, as well as under the governments of Tabaré Vázquez, Correa and Maduro, although the causes are different.

When hegemony vanishes, the logics of domination are imposed, which lead us directly to the exacerbation of class, gender, generation and race-ethnicity conflicts, The domination-conflicts-repression triad will affect (is already affecting) women and youth of the popular sectors, the principal victims of the systemic turn to the right.

The second question to take into account is that the political-economic model is more important and decisive than the people who conduct and administer it. In the lefts we still have a political culture very centered on caudillos and leaders, which without a doubt are important, but are not able to go beyond the structural limits that the model imposes on them. Extractivism is the one largely responsible for the crisis that runs through the region, for the erosion that the governments suffer and, in short, is the bottom line that explains the turn to the right of societies.

Unlike the model of industrialization over over substitution of imports, which generated inclusion and promoted social growth, the current extractive model generates social and economic polarization, generates conflicts over the common wealth and destroys the environment. Therefore, it is a model that generates violence, criminalization of poverty and the militarization of societies and territories in resistance.

The inability of the progressivisms to leave the extractive model and the express will of the new rights to deepen it augur times of pain for the peoples. The recent tragedy in Mariana (Minas Gerais) because of the rupture of two of the Vale mining company’s dams, [1] which provoked a gigantic tsunami of mud that is leveling cultivated fields and entire towns, is a small sample of what awaits us if a limit is not set on the mining-soybean-speculator model.

In third place, the end of the progressive cycle supposes the return of the antisystemic movements to the center of the political scenario, from which they had been separated by the centrality of the dispute between the governments and the conservative opposition. But the movements that are activating are not the same, nor do they have the same modes of organizing and of doing, as those that championed the struggles of the 90s.

The piquetero (picketer) movement no longer exists, although it left deep footprints and lessons, and an organized sector that works in the villas in the big cities, with new kinds of initiatives like the popular high schools and women’s houses. The campesino movements, like those of Sin Tierra, have been transformed by the geometric expansion of soy, but new subjects emerge, more complex and diverse, where neighbors of those affected by mining or agro-toxics participate, as well as a wide gamut of health, education and media professionals.

The impression is that we are seeing new articulations, above all in the big cities, where the demands for more democracy and inequality inundate the trenches of the parties and unions, but also of the movements of the neoliberal decade of privatizing.

Lastly, the progressive cycle must close with a serene analysis of the errors committed by the movements. It would be demoralizing that in the next cycle of struggles they repeat the same errors that have affected autonomy in these years. It’s probable that the greatest difficulty to confront consists in knowing how to accommodate the double activity of the movements: the struggle against the model (the defense of one’s own spaces, mobilization and formation) and the creation at each possible level of the new (health, production, housing, land and education).

While street action permits us to stop offensives from above, new creations are steps in autonomy. They are the modes that we learn to continue navigating in the storms.

Translator’s Notes:

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Friday, November 27, 2015

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2015/11/27/opinion/024a2pol/

López y Rivas: Video for Level 2 of the Escuelitas

The SECOND LEVEL of the ZAPATISTA ESCUELITAS

By: Gilberto López y Rivas / III

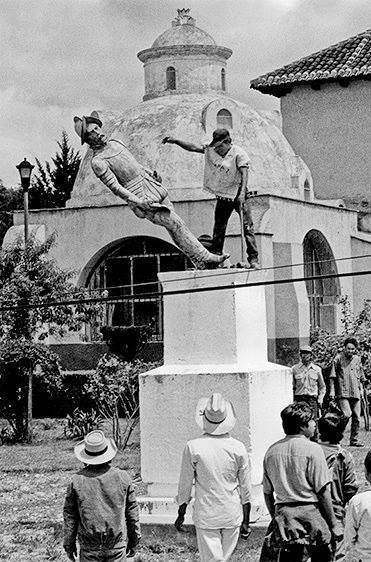

EZLN members brought dow this statue of Diego de Mazariegos on October 12, 1992, more than a year before the 1994 Uprising.

Students of the Zapatista Escuelita (Little School) that hope to pass the second level had access to a video more than three hours long, a significant part of which demonstrates the less known history of the EZLN: the history of the years prior to the 1994 Uprising. This memorable film document, which offers an extraordinary lesson of how to organize in the most adverse conditions, begins with an introduction from Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés, the current spokesperson of that political-military organization. Around 30 local responsables coming from the five Zapatista Caracols gave talks.

In these testimonies they announce, live and in the various languages of the peoples, the difficulties of clandestine work from the crucial years of 1983 and 1984; the slow and tortuous process of taking consciousness, explaining the 13 demands, the exploitation, capitalism, imperialism, the bourgeois State, criticism and self-criticism. They talk about the first recruitment of members, about the forms of secret communication and discretion, meeting with each other in the milpa or in the coffee field, in the mountains, avoiding the traveled roads, walking along the dirt paths, at night, many times in the rain, enduring hunger, mud, cold and heat, all for the struggle.

They detail the security rules for not disclosing the presence of the organization in its infancy, including sharing it with family members, neighbors and friends, “burning the notes so that the enemy would not know about us.” They remember the sacrifices and zeal of the first militants, of the initial desertions and treasons of the splits, as well as the compas that continue firm in the struggle. They describe the tasks of the local and regional responsables throughout the years, as well as the sacrifices and the conditions in which the military preparation of the insurgents and milicianos took place. They looked for secure places for the trainings and, at the same time, the militants bought their weapons, machetes, boots, hammocks, uniforms and batteries; they had “reserves,” because they didn’t know how long the war would last. There was a bakery, a tailor shop, and later a radio. They cooperated among the support bases for that and they worked collectively; the rebellion was assumed as a great task for everyone, while the insurgents gave training to the milicianos and, in the midst of all this hustle and bustle, which finally led to the 1994 Uprising, there was time to “raise spirits,” above all by realizing that more were convinced every day, that there were concentrations of thousands, with those who joined the platoons, battalions and regiments of what would be the Zapatista National Liberation Army. The Indigenous Revolutionary Committee was composed of the zonal and regional spokespersons. Compañerismo and unity, information and formation, the economy of resources destined to mobilization were followed in all these organizing efforts. When the armed and uniformed insurgents arrived in a village, they would make welcoming fiestas with marimba music and dancing.

In the expositions they identified values and qualities for eventual members of the organization; that is, they chose those who “were well-spoken,” demonstrated punctuality, discipline and completion of work, were without addictions, with irreproachable conduct and, above all, who had no contact with the government and the finqueros. [1] The best of these were selected to be local and regional responsables. In these years they were forging the organization’s basic principles: don’t surrender, don’t sell out, don’t give up and don’t deceive the (support) bases.

The reference to the work of the women in the guerrilla organization was very instructive: their first incorporation into peripheral tasks in the beginning, and their passage towards positions and duties with greater responsibility, including those directly related to the war that was being prepared; that is, as milicianas and insurgentas. In the 1993 consultation to decide the start of the war, they also signed the agreement, prepared the food for the milicianos and milicianas that marched at the front. They even made known a military action at an airplane landing strip, in which the women brought down the antenna and expropriated a radio transmitter. Now, they proudly affirm that they have learned a lot: that they are agents, commissioners, midwives and health promoters, education responsables, members of the autonomous governments, commanders and, above all, self-sufficient human beings with rights backed up by the Women’s Revolutionary Law. They maintain that the war is never going to end because “the fucking bad government is always going to betray us.”

It’s also interesting listen to the stories of how the EZLN combined the forms of struggle before the Uprising, with open organizations that answered to their commanders, one of which brought down the statue of Mazariegos [2] on October 12, 1992, in which the indigenous peoples aired their protest against the “celebration” of the invasion of our continent and, at the same time, a general rehearsal for the taking of San Cristóbal de las Casas in 1994.

What shows through is the pride and affection for the “organization,” for the history that its supporters are unraveling, each one in their fashion, from their particular experience and in their own forms of oral expression. They declare that they will never give themselves up as conquered, that the Zapatistas, 20 years after the declaration of war, have their autonomous governments, without depending on the bad government, and that this future they are constructing is forever.

They conclude by pointing out that they prepared the Second Level course for the Escuelita Zapatista with a lot of love, and starting with a commitment to the people of Mexico, to the millions of Mexicans, to whom they deliver this seed of organization and resistance.

Notes:

[1] Finqueros – Ranch owners

[2] Diego de Mazariegos was a Spanish colonizer who invaded Chiapas.

——————————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Friday, November 6, 2015

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2015/11/06/opinion/023a1pol

Escuelitas Zapatistas, an invitation for us to organize

Galeano (aka Marcos) at the Seminar on Critical Thought versus the Capitalist Hydra

By Carolina Dutton

“The EZLN, through its Sixth and International Commissions, will announce a series of initiatives, of a civilian and peaceful character, to continue walking together with the other Native Peoples of Mexico and the whole continent, and together with those who, in Mexico and in the entire world, resist and struggle below and to the left.” (The EZLN announces its next steps) Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, December 30, 2012.

From the beginning the vision of the Zapatistas has been to construct their autonomy together with the people of Mexico and the world. Massive support from the Mexican public and world opinion saved them from being wiped out by further massacres in 1994. Later that year they organized a national democratic convention in Chiapas. In 1995 they held a consultation with the people of Mexico to ask the people in all parts of the country about indigenous culture and the steps Mexico needed to take towards dialogue and democracy from below. They also presented their 13 demands for land, housing, work, food, health, education, culture, information, independence, democracy, liberty, justice and peace, which are not just for them, but rather for all people from below. More consultations were done throughout Mexico in 1999 and the March of the Color of the Earth visited 13 states of Mexico in 2001. Then came the 6th Declaration and the Other Campaign in 2005-6. The Escuelitas (Little Schools), which began in 2013, are their most recent way of reaching out to others struggling against capitalism and working to create another world. In Level 1 of the Escuelitas, the Zapatistas permitted us to participate in their resistance and thus be directly connected to them. In Level 2, they connect with us by sharing online so that many who can’t go to Chiapas but who can learn from the Zapatistas’ experience organizing and building their organization in clandestinity.

In the first level of the Escuelita we lived in Zapatista villages and the compas shared with us their everyday resistance and their construction and practice of autonomy mostly from 1994 to the present. We worked with our host families on their everyday economic activities, everything from carrying water and collecting firewood to tending the cattle, cultivating the milpa [1], coffee and sugar cane. We visited their autonomous schools and health centers and learned about autonomous government. Our host families sometimes shared their history with us around the dinner table, how things have changed for them now that they live autonomously and their participation in the uprising. We were given readings, which were testimonies of many Zapatista women and men who had served in various levels of civilian autonomous government.

The second level of the Escuelita has been conducted entirely online. The readings emphasize the need to organize our communities to resist the capitalist hydra economically and politically. We were given the link to a video where the Zapatistas shared how they formed their organization and how they organized and recruited new members, educated, encouraged, and protected each other as a clandestine organization beginning as early as 1983 up until the 1994 uprising, when they became public. The video consisted of testimonies from those who had been and some who still are both local and regional responsables [2] during clandestinity. Responsables spoke from each of the five Caracoles, or centers of Zapatista regional government: Caracol 1 La Realidad, Caracol 2 Oventic, Caracol 3 La Garrucha, Caracol 4 Morelia, and Caracol 5 Roberto Barrios.

The Zapatistas made it very clear their reasons for sharing this precious information. They hope that learning how they went about organizing will give us ideas and help us organize in other parts of Mexico or in our own communities in many parts of the world. They are very aware that they cannot do it alone, that they need us to organize too, but that we may need to do it in our own way depending on our unique situations. We are all in this together and we need not only each other’s support but also each other’s vision.

In the Escuelita 2 video the local and regional responsables during the EZLN’s 10 years of clandestine formation shared with us their tasks and sacrifices. The local responsables coordinated the organization’s work in the communities. They observed how people participated in the community and recruited new members who exhibited responsibility and understanding. They were in charge of orienting new members and raising their consciousness to understand why their lives were so hard and the necessity to struggle and to study in order to prepare the struggle.

The responsables also coordinated local security. Women were especially important for security since they usually stayed in the community and were aware when people who didn’t belong there were present. The responsables, both men and women, also convened meetings and assemblies. Sometimes meetings took place in the middle of the night on stormy nights when people would not be seen or heard as they left home and traveled to a safe meeting place.

Local responsables also organized the training and equipping of the milicianos. [3] They also organized collective work, which was necessary to free up time for those with other responsibilities in the organization as well as to earn money to buy necessities for the struggle including boots and weapons. The sewing collectives sewed uniforms. The women collectively made tostadas and women and men collectively grew the food for the milicianos and insurgents. Many women and men had responsibly for this collective work and for security but the responsables oversaw the collectives in their area and communicated information about any problems and needs to the regional responsables.

The regional responsables oversaw the work of the organization in wider regions. They oriented the local responsables, prepared and encouraged the milicianos and raised the consciousness and understanding of members of the organization. In isolated areas compas often became discouraged so the responsables organized fiestas so that the members in a region could meet each other and see how many hundreds and thousands of compas were committed to the struggle. The Zapatistas love parties, all without drinking alcohol, which was against the EZLN’s rules.

So why have the Zapatistas decided to share this information with us now? They want us to organize too in our own way. They need people all over Mexico and the world to organize and to be in touch with them. It is the only way our movements can resist the capitalist hydra whose tentacles reach all corners of the earth and all aspects of life. I think they also want to share this history with their youth. An entire generation has grown up since the uprising that did not participate in building the organization and preparing for war. Zapatista resistance now requires creativity and sacrifice but it is very different. It is important that the youth know what came before, what has changed, and the ingenuity, discipline and sacrifice that went into building the organization they have always known.

Our exam to pass Escuelita 2 consisted of 6 questions, questions which each of us had to write and ask the Zapatistas. As Subcomandantes Moisés and Galeano explain: “The questions are important, as is our Zapatista way, they are more important than the answers… What interests the Zapatistas are not certainties but the doubts because we think that certainty immobilizes, that one is still, content, sitting still and not moving, as if we had arrived or we already knew. On the other hand, doubts, questions, make one move, search, not be still, not be in conformity, like day and night don’t pass, and the struggles from below and to the left are born of inconformity, of doubts and restlessness. If one conforms it’s that one is waiting to be told what to do or has already been told. If one is not in conformity, one searches for what to do.” (Second Level of the Little School, July 27, 2015).

Notes:

[1] A milpa is much more than a field of corn. It is a diverse area of cultivation. The dominant plant is the basic grain of the people, corn. Beans grow up the corn stalk, different forms of squash creep along the ground and many medicinal and culinary herbs grow in and around the milpa.

[2] A responsable is the person responsible for a certain task or group of tasks. In the context of early EZLN organizing the responsable seems like more of a political operative or organizer.

[3] The milicianos were and still are somewhat like the National Guard. They have military training, but are not insurgents, and can be called to active duty in an emergency.

A Reflection and application from the Second Escuelita

[Last Tuesday evening, members of the Chiapas Support Committee got together and shared what they learned from the background readings and Video for Level 2 of the Escuelitas Zapatistas (Little Zapatista Schools). Several people shared their reflections on Level 2 in articles for our Chiapas Update newsletter. The first is posted below.]

“TRYING ON A SHOE, OR CLOTHES:” A Reflection and Application from the Second Escuelita

Zapatista musicians play at the Homage and Seminar in Oventik, May 2015.

By: Todd Davies

“Por eso decimos que somos muy otros, muy otras, nosotros, porque es que vamos como si fuera el zapato, la ropa, se mide uno si le queda o no le queda pues, prueba, y si no hasta que encuentra la que sí le queda pues. Así somos, compañeros, compañeras, hermanos y hermanas, de lo que es nuestra resistencia y la rebeldía.”

“That is why we say we are very other. Because we move as if trying on a shoe, or clothes – you measure and see if it fits, try it on, and if not then you keep looking for the one that fits. That’s how we are, compañeros, compañeras, brothers and sisters, that is what our resistance and rebellion is about.” — Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés, “Resistencia y Rebeldía Zapatistas II” (“Resistance and Rebellion II”), 7 May 2015

One of the themes running through the assigned readings and video recording for this year’s second level of the Zapatista’s Little School (Escuelita) was how much the compañer@s living in Zapatista Territory have learned through practice. I have long thought of the practice-driven approach of the Zapatistas as having lessons for us in movements here, but I had not seen such a clear explanation of both the philosophy underlying this approach, and some of the specific lessons it has taught, until I made my way through the curriculum of the segundo nivel.

A few years ago, after describing to fellow activists my understanding of the Zapatista phrase caminar preguntando (walking while asking questions), I was asked whether the Zapatistas’ method of learning along the way was similar to Marxist or religious concepts of “praxis”. Although I was familiar with this term, I wasn’t sure what to say at the time, so I hedged. After thinking about it a bit more, I realized that when friends of mine in movements had used the term “praxis”, they seemed to mean a form of practice that starts with an overall theory and then applies it through action. Part of the idea is that everyday practice is the means by which oppressed people actually learn how to change the world: understanding comes from doing, not just from hearing or reading. But particularly in movements of the left in this country, the use of “praxis” seems also to be infused with Gandhian and/or vanguardist thinking. Only through praxis can we bring about revolution, under this understanding of the concept, because without action, our theories are just words. Talk is cheap. “You must be the change you wish to see in the world,” as Gandhi said. And this is so because you must lead by example. Who would trust a guru who did not follow his own teachings?

So I sensed that the Zapatista approach to practice was not quite captured by the term “praxis” as I had generally seen it employed, because in caminar preguntando we begin by assuming that whatever we think now is probably wrong in crucial respects, and that we will learn what our theory should be as we go along, rather than primarily learning to appreciate what it means and demonstrating to others that we can apply it. As Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos (now Galeano) wrote in 2004: “We are trying, with our clumsiness and our wise actions, definitions or vagueness, just trying, but putting life into it, to build an alternative. Full of imperfections and always incomplete, but our alternative.” Not the words we expect from a guru or vanguard.

In the assigned readings for the second level, Moisés describes an example of how the Zapatistas have moved from “shoe to shoe” in their search for a better fit. Communities began by working collectively 100% of the time. There would be, for example, one milpa (corn field) for everyone. Over time, however, they learned that this approach worked less well than more complex arrangements that involved a mix of collective and family allotments and labor. The division of time now varies by community, and there are different levels of collective work and control: region, autonomous municipality, and zone, in addition to the community. The goal was to create a robust agreement that worked for everyone and was sensitive to problems and contexts (weather events, shortfalls, over-harvesting, different family sizes, needs, etcetera…).

Moisés says, “Here what we learned in practice is that what we were doing wasn’t working, that is, we made a mistake, and we failed when we required 100% collective work. We saw that this didn’t work because there were complaints; there were a lot of problems.” I think it is useful to contrast this with the more ideologically or theory-driven approach that we often see in movements, both capitalist and anti-capitalist: Those who complain are lazy (or are counter-revolutionaries). Problems come from those who are unproductive (or selfish).

The Zapatista approach is piecemeal: finding a shoe that fits is distinct from finding a good shirt or blouse. Theory-driven politics, by contrast, tends to push us to choose between entire wardrobes. In a widely read piece from earlier this year, L.A. Kaufman wrote about “The Theology of Consensus” in a way that portrayed consensus decision making as a religious doctrine that should be abandoned because it failed, for example, to yield effective decisions in the general assemblies of the Occupy movement. A Zapatista-like assessment would, I think, be more analytical. It would look at the many elements that vary across consensus procedures and ask which ones are sources of problems, and which should be retained depending on the context. The whole-wardrobe approach, by contrast, urges us to throw out everything and start over. That only makes sense if there is nothing in the wardrobe worth keeping.

The Zapatistas have held together as an organization for 32 years, and the rebellion that began on January 1, 1994, will soon celebrate its 22nd anniversary. What Moisés tells us in the readings for the second Little School is that the movement has survived this long because it has prioritized the organization and its radically democratic principles, has pursued what works well, and has modified what was not working. Such a simple lesson! But one that is ripe for application in our own attempts to build community and autonomy here in the bay area.

Ejido Morelia: the Army’s impunity

The victims’ family members attend the recognition of responsibility in San Cristóbal. Photo: Chiapas Paralelo

By: Miguel Angel de los Santos*

In January 1994 an internal armed conflict began in Chiapas, when the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, its initials in Spanish) declared war against the Mexican National Army and took various municipal capitals. Armed conflicts are governed by the rules of International Humanitarian Law, among them the Geneva Conventions and their protocols, which establish, among other things, that the parties in conflict must respect those who do not take part in the hostilities, and those who, having taken part, are injured or have been taken prisoner. Those who do not comply with these norms incur war crimes and violate human rights.

It was within the above context that a Mexican National Army brigade entered the Ejido Morelia, in the municipality of Altamirano, Chiapas, the morning of January 7, 1994. They detained 33 indigenous men, who they submitted and laid face down on the basketball court. They also detained Severiano Santiz Gómez, Sebastián Santiz López and Hermelindo Santiz Gómez, who were separated in order to take them to the sacristy of the church, where they were tortured, for allegedly belonging to the EZLN. This was the last time they were seen or heard. A few weeks later, their remains appeared near the ejido. They had been executed by their captors in violation of the norms of International Humanitarian Law.

Despite clear evidence, the Mexican National Army has denied responsibility for the acts and the Mexican State continues protecting it, refusing to investigate or simulated doing so, in order to avoid punishing the military personnel involved and responsible for the arbitrary execution.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) had already pointed out the Mexican State’s international responsibility for the violations that the soldiers incurred. Such reproach is clear in the background report number 48/97, derived from case 11.411, known as Severiano and Hermelindo Santiz Gómez “Ejido Morelia.” [1]

Almost twenty-two years later, the State has accepted its international responsibility in the human rights violations that the Mexican National Army committed, and in the terms in which the IACHR would point it out. Nevertheless, this admission has not represented punishment of those responsible.

On November 10, the signing of an Agreement for Attention to the Background Report No. 48/97 was carried out. Representatives of the Mexican State and the widows of the three victims signed the agreement.

Starting with the international principle that one who violates an international obligation, like the rights provided in the American Convention on Human Rights, is obliged to make reparations, the agreement contemplates the reparations measures agreed to by the parties, and that the State has to implement.

About the factual basis for the referenced background report, the ministerial investigation will continue until the complete clarification of the facts and the sanction of those responsible. They also agreed on diverse rehabilitation measures for family members of the victims; a public act of recognition of responsibility; the construction of a community park and corresponding compensatory indemnifications.

The path of justice is open, and the agreement represents an important gesture from the Mexican State to recognize and admit its responsibility in the deprivation of the lives of Severiano Santiz Gómez, Sebastián Santiz López and Hermelindo Santiz Gómez; nevertheless, it turns out that the human rights violations will only be resolved and compensated for when those responsible are taken to the courts and a sanction is imposed on them.

* Miguel Angel de los Santos is the lawyer for the victims’ families.

[1] http://www.cidh.oas.org/annualrep/97span/Mexico11.411.htm

——————————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by Chiapas Paralelo

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Friday, November 13, 2015

http://www.chiapasparalelo.com/opinion/2014/01/ejido-morelia-veinte-anos-esperando-por-la-justicia/