Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Supreme councils in neoliberal times

For Everyone, Everything. For Us, a Candidacy!

By: Magdalena Gómez

Three days ago, the National Indigenous Congress (CNI, its initials in Spanish) published the denunciation of the Indigenous Council of the Trueque (CIT, in Spanish) regarding the aggression (threats of violence and provocations) at the Tianguis of the Trueque in Tianguistenco, state of Mexico, on the part of a group headed by an alleged “supreme chief” of Coatepec. The CIT is made up of Nahuas, Tlahuicas and Otomies in the la region. Every Tuesday they attend to exchange (barter) firewood for basic foods. In their story appears the tip of the iceberg of neo-indigenismo, which despite being the gatopardista [1] version of the traditional, turns out to be necessary to consider. Moreover, facing the proximity of an electoral process in 2018, in which the CNI and its Indigenous Government Council (CIG, its initials in Spanish) have decided to participate, through their spokesperson María de Jesús Patricio, as an independent candidate to the Presidency of the Republic.

So, they point out in the referenced denunciation: “Last July 1, before some 50 people, in San Nicolás Coatepec, the mayor of Tianguistenco, swore into office the ‘Pluricultural Indigenous Municipal Council of Tianguistenco’ without consulting the communities or having the corresponding assembly minutes, because of which the situation is aggravated in many municipalities where they have placed ‘tlatoanis’ and ‘supreme chiefs’ that respond to the interests of the political parties and have caused serious conflicts in the communities por su unmeasured ambition for power and converting themselves into puppets of the system.”

The indigenous governor of the state of Mexico and a member of the CNC [2] is Fidel Hernández, who together with Hipólito Arriaga Pote, “national indigenous governor,” promotes the so-called national government of the indigenous peoples, pointing out that they are elected through uses and customs and saying they are ancestral authorities.

At first blush, they evoke what was the official impulse for so-called supreme councils in the 1970s, except that now a good part of the indigenous peoples are organized and resist the onslaught of dispossession on their territories, at the same time that they construct, in fact, authentic spaces for autonomy. Also, this movement, which the CNI created 20 years ago, while it had previous trajectories, was with the Zapatista Uprising and the posture of its leadership, which contributed decisively in the struggle for the legal recognition of their rights as peoples, expressed in the (still) unfulfilled San Andrés Accords.

The paradox is that the so-called governorship wraps its discourse in what Zapatismo and the CNI achieved constitutionally, to which they had objected due to the Congress’ distortions and mutilations of what had been agreed upon in the San Andrés Accords. Through the digital networks we find said “national governorship” in the delivery of the staff of command to their supreme chief, indeed, you guessed it: Enrique Peña Nieto.

We can also know the discourse of the alleged ancestral authorities, which, not by chance, they promote their movement from the state of Mexico and, also not accidentally, they count on economic support from federal institutions. They claim to have indigenous governors throughout the country, elected by the dedazo (being fingered or selected by the powerful), which is the use and custom of the political class. They state that they struggle for the autonomy that is in the Constitution, in Article 2, and they come to argue that they are a national government parallel to the federal government. Their struggle is on two fronts: the budgets assigned to them in the states and the demand that the INE guaranty them special norms directly, without political parties to accede to federal and state deputy and senator positions.

They have advisors throughout the country that prepare legal documents for them, wherein they transcribe how much regulation exists in indigenous matters. They recently presented to the United Nations Permanent Forum for Indigenous Questions, denouncing the INE. They have close to four years with their plan; they move throughout the country and outside of it, without making too much noise, until now.

However, in fact, they usurp the indigenous peoples, distort the meaning and function of the elders, the wise ones, the grandmothers, grandfathers and they enjoy the not so implicit endorsement of official spaces. For example, the INE accredited its “national membership” to participate in a consultation about indigenous electoral districting, with the CDI’s support [3], planned as they know how to do, with a protocol, of course. In the end, all a contrasting scenario with the CNI, which, while it has reiterated that it will not contest in the election to look for votes, it can be affected by activism promoting the community’s vote in exchange for gifts, provoking divisionism, as to which one represents the “national indigenous governorship.” The CNI’s strategy is different, it seeks to give voice, to those above that don’t listen, less in electoral times, promoting organization with the communities, but also to show society the generalized impacts of the extractive model, not just for indigenous peoples and, on the way, approaching with them the mirror of the prevailing racism.

[1] Gatopardismo is to give the appearance of changing something when nothing really changes.

[2] The CNC (Confederación Nacional Campesina) is the national campesino organization associated with the PRI (the political party currently in power).

[3] CDI – The initials for the Mexican government’s National Commission for the Development of the Indigenous peoples

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Tuesday, July 25, 2017

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2017/07/25/opinion/016a1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The hour of disobedience

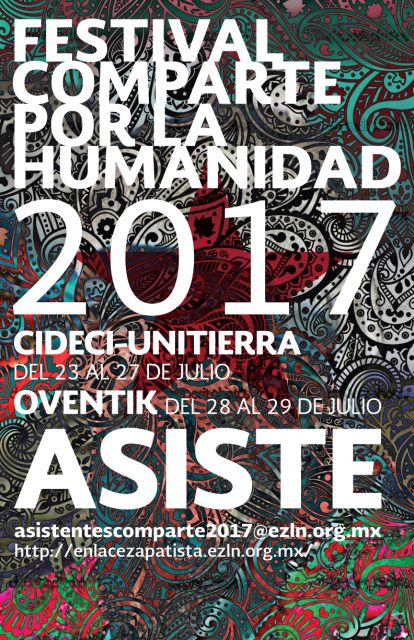

Zapatista women and men performing at CompArte in Chiapas.

By: Gustavo Esteva

It’s only natural that Mr. Trump would boast of having several multi-millionaires in his cabinet and would add that, obviously, he doesn’t want any poor people there. What ought to worry us is that many poor people share that judgment. The rich would be there because of a personal aptitude that would also give them the ability to govern; the opposite would be applied to the poor, who would be considered inept.

This aberrant configuration of the mind, which forms entrenched convictions and general behaviors, is also applied to the belief in a supposedly democratic form of government, in accordance with which Mr. Trump was elected and that currently dominates on the planet. Discontent with existing governments increases, but doesn’t affect that generalized belief in the validity of their formative training and in their reason for being. When someone questions its legitimacy, his removal can be proposed through “democratic” proceedings, as has been done in Mexico since Calderón and is now done through Mr. Trump’s Russian dossier. But the system itself, based on a hierarchical structure that converts citizens into subjects that ignore their condition or don’t know how to get out of it.

A deviant mentality, the same one that makes the rich apt and the poor inept, would give the rulers the right and the ability to act as they are doing, at the service of the 1 percent and not of the majority of the people, who they oppress in every conceivable form. That mentality processes this fact with an illusion: the next one may be better; he will use the power we give him in our benefit.

We need to examine carefully the roots of that mentality and the conditions that made it possible. Because of that mentality, many people deposit their faith in a charismatic leader, a party, an ideology, a coalition of forces or any combination of these elements. They trust that their electoral victory will remedy our evils and will make the situation we face bearable. With a good “country project,” appropriate advisors, effective commitments and, above all, an honest and capable leader at the top, we’ll get out of the current horror actual. All that can be applied without difficulty, for example, to the millions that still continue to follow López Obrador, to militants of his party and of other institutes, to savvy analysts and to prominent intellectuals, who all share that mentality.

Its origin is clear: colonization. Having that mentality is a necessary consequence of the way in which they colonized us. Since long ago, in countries like Mexico, colonization does not necessarily suppose the loss of political sovereignty, but our “independence” has become more and more relative… and sovereignty more and more illusory.

The origin of that mentality can be traced to the formation of what we call the West. It does not seem useless to resort to a classic formulation of Plato, who wrote the following in The Laws:

“Of all the principles, the most important is that no one, be it a man or a woman, ought to lack a boss. Neither should anyone’s spirit become accustomed to being permitted to work following one’s own initiative, whether at work or for pleasure. Far from that, in war as in peace, every citizen will have to look up to the boss, faithfully following him, and even in the most trivial matters must remain under his command. So, for example, he must get up, move, bathe, or eat… only if he has ordered him to do so. In a word: he must teach his soul, through long-practiced habit, to never dream of acting independently, and to become totally incapable of it (…) There is no, nor will there ever be, a law superior to this or better and more effective for assuring war’s salvation and victory. And in times of peace, and starting with earliest childhood, that habit of governing and being governed must be stimulated. In this way, the last vestige of anarchy must be erased from the life of all men, and even from the beasts that are subjects at their service.”

This formulation is politically incorrect today. No one would dare propose the system that is called democracy and dissembles in a thousand ways the condition that Plato describes. But all those veils cannot hide the submission to a structure in which there are the rulers and the ruled, some who govern and others that obey, and even less hide the fear of “anarchy,” of resistance to being governed, the deep desire to govern themselves… which is very general.

From the West itself, however, resistance to that state of things was affirmed a while ago. Howard Zinn, for example, said not so long ago: “The world is upside down, things are completely wrong. It’s not about civil disobedience. Our problem is civil obedience. Our problem is that people are obedient all over the world in the face of poverty, hunger, stupidity, war and cruelty. Our problem is that people are obedient when the prisons are full of small-time crooks while the big crooks are in charge of the country. That’s our problem.”

That is truly our problem. And it’s not resolved changing the leader, but rather by abandoning the hierarchical system, which is truly the option that the Indian peoples that have 500 years of confronting colonization have created from below.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Monday, July 17, 2017

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2017/07/17/opinion/017a2pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

CompArte 2 | The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival | Oakland, CA

CompArte 2 | The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival

CompArte 2 | The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival

Saturday, August 12, 2017 | 1:00-10:00pm | Free/Gratis

At the Omni Commons, 4799 Shattuck Ave, Oakland, California 94609

CompArtistas SCHEDULE

1:00-1:30pm Welcome & Opening by Chiapas Support Committee Oakland & Calpulli Huey Papalotl

1:30-3:30pm Workshops for human liberation

• What is Zapatismo?

Led by members of the Chiapas Support Committee, presentation & dialogue on the history of the Zapatista struggle and movement in Mexico; guiding principles & values, building an Indigenous Council of Government with Indigenous people and what Zapatismo means in the U.S.

• Learn the basics of Danza Mexica with Patricia Chicueyi Coatl from Calpulli Huey Papalotl:

Through centuries, through millenia, Danza Danza Mexica-Chichimeca , Mitotiliztli, has been a form of education and discipline for our Native Anahuacan people. Brave guerrerx have so valiantly fought to protect these Sacred Traditions, especially Tlahtouani Cuauhtemoc, right after the European Invasion, and our beloved Tlacatecuhtli Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution.

Come learn the basics of strong and beautiful form or danza-prayer created by our Anahuacan Ancestors.

• Son Jarocho writing verses & dancing

María De la Rosa & DíaPaSon artists facilitate community art-making using son jarocho- a living tradition of music and poetry. You’ll learn some basic beats on percussive instruments and then we’ll show you how to layer them to create a basic groove and be “present” with fellow workshop participants. Once we’ve locked in, we will guide you to compose lyrical poetry that expresses collective, universal concerns of the community and set it to melodies used in “Señor Presidente” and “El Canto del Grillo”.

• From the Underground Railroad to the new codes & emblems of solidarity

Marshall Trammell of Music Research Strategies leads participants in an exploration into the ‘technologies’ of warrior ethos of the UGRR-era narratives of solidarity ‘technologies’ as a means to assess social impact methodologies for generating new “codes” and emblems of solidarity into everyday life today.

3:30-4:30 pm Music, Spoken Word & Poetry in resistance against the walls of capitalism

• Francisco Herrera, Caminante Cultural, music

• Elana Chávez, poet

• Muteado Silencio, spoken word

• Cory Aguilar, spoken word

• PoesíaMaríaArte, spoken word

4:30-5:30pm Community meal with tamales, zapatista coffee & aguas frescas

6:00-10:00pm CompArte in Concert for Humanity, Against capitalism, war & racism

• DíaPaSon, son jarocho music & dance

• Black Fighting Formations: Mogauwane Mahloele & Marshall Trammell, South African and African American percussinists perform warrior ethos ritual.

• uPhakamile uMaDhlamini, poet

• Muteado Silencio, spoken word

• Naima Shalhoub+Band

• Arnoldo García, poet

• PoesíaMaríaArte, spoken word

• Los Nadies, dance from below

* * *

Compartir ZapatistArte

CompArte is a play on the Spanish words compartir (to share) and arte (art), so it’s a festival of sharing art in all it’s forms: music, dance, poetry, painting, drawing, sculpture, etcetera, to dream a different world where we all fit.

CompArte is also an international festival, first convened by Zapatista communties in 2016 to celebrate art and culture as a catalyst for social change, in rebellion against capitalism and all its walls of exploitation and oppression: racism, sexism, classism, xenophobia, transphobia, homophobia, english-only mentalities.

Zapatista supporters created CompArte Festivals all over Mexico and in other countries in 2016. Here in the Bay, the Chiapas Support Committee held a CompArte Festival in Oakland, too.

This year, thanks to support from the Akonadi Foundation, we are able to expand CompArte to add music, dance, workshops, food and much more, free for all our communities.

CompArte brings together the culture, imagination and dreams of those who organize and resist the walls of capitalism and work to build a more just and free community where everyone belongs.

CompArte 2 The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival will be featuring rap, singers, painters, poets, thinkers, revolutionaries, bands and working people bringing their voices, visions and talent to listen to each other and dream out loud the relationships and community of communities we want to make us safer and powerful for justice, solidarity and love.

CompArte will feature a day-long art exibit with the painters and artists on hand to share their work’s relavance to resisting capitalism and constructing another world.

CompArte 2 comes together to explore how to make cracks and fissures in the walls of racism, classism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, exploitation and abuse of women, girls, boys, children, the elders and youth, in other words, the planet.

CompArte 2 is a space to dream awake and aloud the world we want to live, work, study, worship and play in.

*

The Chiapas Support Committee will be asking those attending to make contributions that will all be given to the Zapatista communities in Mexico.

For more information or to contact the Chiapas Support Committee:

Email CSC: enapoyo1994@yahoo.com

Check out our blog: https://chiapas-support.org/

CompArte 2 The Emiliano Zapata Community Festival in part is made possible by the generous support of the Akonadi Foundation and by the sacrifices, struggles for justice, the dignity and global leadership of the Zapatista communities.

Carlos Gonzalez: “We are going to reorganize the National indigenous Congress”

Carlos González of the National Indigenous Congress with Marichuy.

Carlos Gonzales, a member of the Organizing Committee of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI, its initials in Spanish) was invited on UDGTV radio, where he clarified several things, primarily about the CNI’s process, remembering the CNI’s birth on October 12, 1996, to try to join the country’s indigenous peoples together with two proposals:

- The recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples in the San Andres Accords (1996-2001).

- The reconstitution and reorganization of the Indigenous Peoples that were and continue being devastated by the conquest.

In two decades of existence, Carlos insists that the CNI served as an inspiration, and now with the proposal the struggle of the indigenous peoples becomes visible again, but also the National indigenous Congress.

The CNI did a re-organization in 2013 to form this proposal for the Indigenous Government Council. The proposal’s origin is the state of war that exists in the country. We Indigenous were destroyed, dispossessed, but above all else, since the 80s there is a decided process of physical and cultural extermination. The Indigenous Peoples are obstacles to the development of capitalism.

We Indigenous Peoples have a millennial collective relationship with the land. In 12 years we see how indigenous languages have been extinguished, as Indigenous Peoples had to migrate in massive numbers to the cities or to the United States.

War of extermination

To the question of whether it’s exaggerating to talk about a war of extermination, Carlos Gonzales answered clearly that the Kochimia peoples have lost their language, the Kumiai Kiliwa peoples only have 50 men and women, the Ukapa people are less than 200 and their territory is occupied by foreign companies for mining projects, toxic waste dumps, and wind farms. The Raramuris say that in the last 10 years 30% of their population has lost their language. It’s a cultural extermination that accompanied the physical and material extermination, which has as its goal the dispossession of territories.

Losing the language is losing a relationship that humanity has with nature, the way in which we name things, implies unique thought. Losing a language is to lose a way of naming, relating, becoming familiar with and knowing our world.

Dispossession is not only for the indigenous peoples, but also in the cities (…) like water, housing, exploitation, low salaries, intense work, poverty… it’s the same problem, it’s dispossession and exploitation.

The proposal that we are making, and successfully attained, is to make the indigenous peoples visible. We have now made up our CIG, with one man and one woman from each people of the CNI, and that CIG is a candidate to the presidency of the republic. We want to put the indigenous problem on the national agenda, like the Zapatistas did in 1994, so that their poverty and exploitation are known in the entire world.

We want that proposal to create a bridge to the indigenous peoples that do not participate in the CNI and to Civil Society in order to construct a different Mexico. We are going to construct that program. What’s certain is that we no longer want that capitalism and we no longer want that political class. We want to say that there is another form, another way of governing this country. We don’t want to give money to that gang of thieves so that they leave us in violence and give the country’s resources to foreigners. Better we govern ourselves!

Autonomy

We think about forms of Self-government, each community, each people according to their culture, each non-indigenous urban society according to their historic walking, to their own identities, can and must construct self-government; that’s what we think. Look at the Zapatistas and their Good Government Juntas and their autonomous municipalities, those of Cherán have a council of Elders, the Yaquis have a traditional guard, those in Ostula have a communal guard. Those are definitely models and there are many proposals of autonomy. Autonomy is the exercise of freedom.

What’s important is the organization of those below. We say that the conditions for human life are being destroyed by capitalism, we propose that we can govern ourselves and from below. We are going to occupy the electoral space that is the space of those above, of the rich, of the capitalists, of those who have the monopoly on the political life of this country or think they have, but that space isn’t useful for approaching the common people, the urban and indigenous collectives that are below, within the logic of organizing ourselves.

Knowing whether we win or not is secondary. What interests us is to construct something new.

What’s coming

In the coming weeks we are going to elaborate a work proposal. We are going to present it to the CIG to be revised, modified and approved within the logic of generating a territorial political structure for 2018, and to bring together the signatures that are now almost one million. We are going to reorganize the National Indigenous Congress the same way; before it was only a place for assembly, now it must re-vitalize its organization fundamentally to generate a successful communications policy, indigenous or non indigenous, to be able to articulate with civil society organizations and finally for going out beyond the country, to Latin America and proposing those themes.

Challenges

The organizational challenge is first, we are being diminished in the organization that we have had; a national organizational structure must be formed to be able to articulate with all the peoples and communities of civil society. One must not fall into the temptation to accumulate votes, to compete with other parties, to not fall into the temptation of the vote, of the power, of wanting to win. One must generate the idea and awareness; that is what we want.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Thursday, July 13, 2017

http://espoirchiapas.blogspot.com/2017/07/carlos-gonzalez-cni-vamos-reorganizar.html

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Indigenous Me’phaa set precedent in victory over mining project

ME’PHAA VICTORY OVER HEART OF DARKNESS MINING PROJECT

Residents of San Miguel el Progreso Photo: Tlachinollan Human Rights Center of La Montaña

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

The Me’phaa (Tlapaneca) community of San Miguel el Progreso, or Júba Wajiín, in the municipality of Malinaltepec, Guerrero, literally triumphed over the Heart of Darkness mining project through a legal decision of national transcendence. Upon deciding in favor of the petition for a judicial order of protection (an amparo) [1] that said community requested against mining exploitation in that territory of La Montaña of Guerrero, first district judge Estela Platero Salgado conceded as well-founded the concepts of violation of their rights, and that they demonstrated the failure to fulfill the Mexican State’s constitutional and conventional obligation to respect the rights of this indigenous-agrarian community. [2]

In conversation with La Jornada, Valerio Mauro Amado Solano, president of the commission of communal wealth of Júba Wajiín, describes the extractivist spiral that began to hang over that and other neighboring communities since 2010: “First, pure rumors that they were going put mines without any notification from the government. We were the last to know what they sought to do on our lands. It was said that the Secretariat of Economy (SE) granted the concessions. The commissioners investigated and the SE delayed giving a response for one year, and then telling us that yes, it was true. In 2011, an act of the assembly rejected mining and presented it to the agrarian authority. We sought the protection of Tlachinollan (a human rights center with headquarters in the city of Tlapa), and in 2013 our first request for a protective order was filed.”

Miguel Santiago Lorenzo, a Ñuu Savi (Mixteco) representative who presides over the Regional Council of Agrarian Authorities in Defense of Territory, reminds us that the San Javier, La Diana and Toro Rojo concessions remain in effect on Iliatenco and Malinaltepec lands, granted to Hochschild Mining and Camsim Mines. “In the Council we will remain vigilant about what the government seeks to do.”

As an exception, in the Me’phaa agrarian nucleus of Paraje Montero (Malinaltepec) the assembly gave its approval to the Camsim Company. Totomixtlahuaca (Tlacoapa), Colombia de Guadalupe and Ojo de Agua (Malinaltepec) and the communal wealth (commission) of Iliatenco rejected the projects and announced that they would do everything possible so that the exploitation was cancelled.

Maribel González Pedro, Tlachinollan defender, remembers that there were exploration flyovers of that area in 2011. The SE and the state government divulged that the mining potential in Guerrero represented “a great attraction for national and foreign investment.” It’s appropriate to mention that in 2008 the Goldcorp Company occupied Carrizalillo (municipality of Eduardo Neri) for a succulent extraction of gold. Today, the Carrizalillo zone suffers a strong presence of criminal organizations, one of the secondary effects of mining.

In the heart of darkness

The Observatory of Territorial Institutions reported in 2013 that the affiliate in Mexico of the Hochschild Mining Company of Peruvian origin and British capital received two concessions from the SE: Reducción Norte of Heart of Darkness and Heart of Darkness, which encompassed more than 145,730 acres in the municipalities of San Luis Acatlán, Zapotitlán Tablas, Malinaltepec and Tlacoapa, in which they presumed the existence of gold and silver deposits.

Heart of Darkness would be the largest concession in La Montaña, with 108,084 acres, affecting the indigenous agrarian nuclei of Totomixtlahuaca, Tenamazapa, San Miguel el Progreso, Tierra Colorada, Tilapa, Pascala del Oro and Acatepec.

The number of concessions began to grow in 2005, until involving a third of La Montaña, in other words, 19 municipalities that encompass 1,709,240 acres. The majority of its more than 361,000 inhabitants belong to the Nahua, Me’phaa and Ñuu Savi peoples.

The Tlachinollan Center documents that in La Montaña “the federal government has been granting concessions without the consent of the communities.” For 2016, the SE listed 44 concessions in the Costa-Montaña region. Before the violations of their rights, seventeen agrarian communities decided not to give their approval to mining exploration and exploitation. Júba Wajiín adopted the decision in April 2011. In September 2012 it obtained its registry on the National Agrarian Registry.

Valerio Solano emphasizes that the ancestral community of Júba Wajiín was demanding the titling of its lands since the 1940s, and it wasn’t until 1994 that the Unitary Agrarian Tribunal decided in its favor and the presidential decree was issued. “The process took six decades of struggle.” In 2009, the community joined the Community Police (CRAC-PC). Faced with the threat of mining, their conflicts are usually about boundaries with neighbor communities, and about security.

In 2012, the government decrees a biosphere reserve of 387,790 acres in La Montaña, Armando Campos, also of Tlachinollan, remembers. Since 2004, the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources and the National Forest Commission implanted a UN program that promoted community reserve zones. The same agencies and the Guerrero Intercultural Universidad impelled the reserve, which “restricted activities of the communities on their own lands and made them lose the administration of that territory.” The reserve would affect 13 agrarian nuclei in five municipalities. As a reaction, the communities met in October 2012 and ran into the problem of the mining companies.

Santiago Lorenzo, of the Regional Council, recounts that the indigenous blocked the Intercultural University and achieved the rector’s resignation for impelling the reserve behind the backs of the indigenous peoples. The government cancels the reserve. Then the organized communities start planning to resist mining. The council spreads to encompass 200 communities of 20 agrarian nuclei in eight municipalities of the Costa and La Montaña. The Me’phaa, Nahua, Ñuu Savi, Amuzgo and Afro Mexican peoples champion a resistance that has not been defeated. They have in common that they did not react against mining companies on their ground, but rather before their arrival.

Armando Campos, of Tlachinollan, points out: “There have been five years of legal achievements and declarations about territories free of mining. The legal pincers are closed so that no mining company has a margin of entry.” These peoples had previously refused to pay for environmental services. In 2014, they file their first legal action requesting a protective order, and they win it. The SE appeals the decision to the SCJN in 2015. The companies granted the concession to the Heart of Darkness desisted. In November of that year the SE publishes in the Official Journal of the Federation the declaration of freedom of the land.

“Thus, they stopped a protective order that would set a precedent for declaring the Mining Law unconstitutional,” explains Maribel González. “The SE and the Mining Chamber coordinate with each other to throw out the amparo and avoid an analysis of the Mining Law.” In December, the communities ask for protection against the declaration of freedom of lands, which opens the possibility of granting concessions to other mining companies. “The SE argues that Júba Wajiín ‘is not an indigenous community’ and therefore the right to prior consultation does not apply to it, which offends the Me’phaa.” The judge in Chilpancingo receives the amparo and orders an anthropology expert that favors the indigenous. Although the Mining Law does not recognize such a right, the Constitution and international treaties do.

New achievement

Tlachinollan emphasizes that the judge’s decision in the protective order 429/2016, “is a new achievement for an indigenous community and recognition for the tireless and millennial struggle of San Miguel el Progreso to defend its territory and its life faced with the threat that open sky mining represents.” For the first time, a federal court orders that, if the SE should seek to grant new mining concessions there, “it must comply with its constitutional and conventional obligation in matters of indigenous peoples’ rights.”

The Mining Chamber reacted by presenting to the SCJN the Amicus Curie “Study about the Right to Prior Consultation of Indigenous Peoples and Communities and its problem around mining concessions,” where it requests: “the order of protection be denied” that Júba Wajiín requested, and questions whether prior consultation is necessary in a granting of concessions since “there is no susceptibility of real or potential affectation to the rights of indigenous peoples or communities.”

Valerio Solano proudly expresses: “In our territory we have controlled the violence. Neither the narco or the mining companies enter.” And the defenders from Tlachinollan conclude: “The Regional Council and its struggle are referents for what can be attained when the peoples get together to defend common territory.”

[1] An amparo (protective order) has the practice al effect of a restraining order or an injunction. It prohibits someone from doing something in order to protect someone or something. In this case it prohibits mining on Júba Wajiín lands in order to protect people and land in that community against the adverse effects of mining.

[2] This decision seems to have been issued on June 28, 2017.

———————————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Saturday, July 15, 2017

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2017/07/15/politica/010n1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

ART, RESISTANCE AND REBELLION ON THE NET

A Call to join the cybernetic edition of CompArte “Against Capital and its Walls, All the Arts”

July 2017

Compañeroas, compañeras and compañeros of the Sixth:

Artist and non-artist sisters and brothers [hermanoas, hermanas and hermanos] of Mexico and the world:

Avatars, screen names, webmasters, bloggers, moderators, gamers, hackers, pirates, buccaneers and streaming castaways, anti-social network users, reality show antipodes, or whatever-you-call each person on the network, the web, the internet, cyberspace, virtual reality, or whatever-it’s-called:

We are summoning you because there are some questions that are nagging at us:

Is another Internet, that is to say another network, possible? Can one struggle there? Or is that space without precise geography already occupied, captured, coopted, tied, annulled, etceterized? Could there be resistance and rebellion there? Can one make Art on the net? What is that Art like? Can it rebel? Can Art on the net resist the tyranny of codes, passwords, spam as the default search engine, the MMORPGs [massively multiplayer online role-playing games] of the news on social networks where ignorance and stupidity win by millions of likes? Does Art on, by, and for the net trivialize and banalize the struggle, or does it potentiate it and scale it up, or it is “totally unrelated, my friend, it’s art, not a militant cell”? Can Art on the net claw at the walls of Capital and damage it with a crack, or deepen and persist in those that already exist? Can Art on, by, and for the net resist not only the logic of Capital, but also the logic of “distinguished” Art, “real art”? Is the virtual also virtual in its creations? Is the bit the raw material of its creation? Is it created by an individual? Where is the arrogant tribunal that, on the Net, dictates what is and what is not Art? Does Capital consider Art on, by, and for the net to be cyberterrorism, cyberdelincuency? Is the Net a space of domination, domestication, hegemony and homogeneity? Or is it a space in dispute, in struggle? Can we speak of a digital materialism?

The reality, both real and virtual, is that we know next to nothing about that universe. But we believe that in the ungraspable geography of the net there is also creation, art… and, of course, resistance and rebellion.

Those of you who create art there, do you see the storm? Do you suffer from it? Do you resist? Do you rebel?

To try to find some answers, we invite you all to participate… (we were going to put “from any and all geographies”, but we think that the net is the place where geography matters least).

Well, we invite you all to construct your answers, to construct or deconstruct them, with art created on, by, and for the net. Some categories in which you can participate (surely there are more, and surely you are already pointing out that the list is short, but, as you know, “what’s missing is yet to come”) are:

Animation; Apps; Files and databases; Bio-art and art-science; Cyber-feminism; Interactive film; Collective knowledge, Culture jamming; Cyber-art; Documentary web; Experimental economies and finances; DIY electronics, machines, robots and drones; Collective writing; Geo-location; Graphics and design, creative hacking, digital graffiti, hacktivism and border-hacking; 3D printing; Interactivity; Electronic literature and hypertext; Live cinema, VJ [video-jaying], expanded cinema; Machinima; Memes; Narrative media; Net.art; Net Audio; Mediated performance, dance, and theater; Psycho-geographies; Alternate reality; Augmented reality; Virtual reality; Collaborative networks and trans-localities (community design, trans-local practices); Remix culture; Software art; Streaming; Tactical media; Telematics and telepresence; Urbanism and online/offline communities; Videogames; Visualization; Blogs, Flogs [Photoblogs] and Vlogs [Videoblogs]; Webcomics; Web series, internet soap operas, and that which you’ve already noted is missing from the list.

So our invitation is extended to all those persons, collectives, groups, and organizations, real or virtual, that work from autonomous zones online, use cooperative platforms, open source, free software, alternative licenses for intellectual property, and the cybernetic etceteras.

We welcome the participation of all [todoas, todas and todos] culture-makers, independently of the material conditions in which they work.

We invite you also so that different spaces and collectives around the world might show the works in their localities, according to their own customs, ways, interests, and possibilities.

Do you already have something somewhere in cyberspace to tell us, show us, share with us, invite us to build collectively? Send us your link to add to the online exhibition hall of this digital CompArte.

You don’t yet have a place to upload your material? We can offer it to you, and to the degree we’re able we can archive your material so that it is recorded for the future. In that case we would need you to give us a link to the cloud, cybernetic host, or similar thing of your preference. Or send it to us by email, or upload it to one of our clouds or to FTP.

While we are offering to host all the material, because we would like it to be part of the archive of art on the solidarity net, we are also going to link to other pages or servers or geo-locations because we understand that in the age of global capital, it’s strategic to decentralize.

So, as you prefer:

If you want to post the information on your websites, with your ways and customs, we can link to it.

And if you need space, we are also here to host you.

You can write us an email with the information about your participation, for example, the name of the creator(s), title, and the category in which you’d like it to be included, as well as a short description and an image. Also tell us if you have space on the Internet and you just need us to post a link, or if you prefer that we upload it to the server.

The material that we receive from the moment that the convocation is open will be classified in the different categories according to its (un) discipline. The participations will be made public during the days of the festival so that any individual or collective can navigate, use (or abuse) and share it in their meeting spaces, streets, schools, or wherever they prefer.

The participations will be published as posts and links.

We will also publish a schedule for direct streaming. The activities will be archived for anyone who doesn’t get a chance to see them live.

The email to which you should write to send us your links and to communicate with us is:

The page on which the links to the participations will be uploaded, and which will be fully functioning starting August 1 of this year, 2017, is:

On that page, from August 1 until August 12, we will also broadcast streamings and showings of different artistic participations from local cyberspace in different parts of the world.

Welcome, then, to the virtual edition of CompArte for Humanity:

“Against Capital and its Walls, All the Arts… Including the Cybernetic Ones”

Ok, cheers, and no likes but rather middle fingers up and fuck the walls, delete Capital.

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast,

Sixth Commission, Newbie but On-Line, of the EZLN

(With lots of bandwidth, my friend, at least as far as the waist is concerned -oh yeah, nerd and fat is hot-)

July 2017

San Miguel del Progreso and the heart of darkness

San Miguel el Progreso.

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

Malinaltepec is known as one of the municipalities in La Montaña of Guerrero with the greatest social inequality. Its residents lack sufficient nutrition, good health, dignified housing and adequate public services. Now it will also be known for being one of the epicenters of the national indigenous struggle against mining.

One of its indigenous communities, that of San Miguel del Progreso (Júba Wajíin), just obtained a very important victory, as much in defense of its ancestral territory as in the battle to make evident the unconstitutionality of different articles of the mining law, and its use as the principal instrument to legalize the dispossession and looting of indigenous territories.

The history comes from a while ago. Without the consent of the communities that live in La Montaña and Costa Chica, the federal government granted 44 concessions to mining companies. Nevertheless, 17 agrarian communities of the region agreed not to give their approval to carrying out mining exploration and exploitation activities, formalizing their decision in written records of agrarian assemblies or through uses and customs.

One of the beneficiaries, the English company Hochschild Mining, baptized its mining project in the region with the truculent name of The Heart of Darkness, the same name as the famous novel by Joseph Conrad, in which he traces the portrait of Belgian colonialism in Africa. However, the entrepreneurs didn’t have time to enjoy their business. The struggle of the Júba Wajíin community forced Mexican authorities to cancel those concessions between July and September 2015. Questioning the mining law more in depth was thus avoided. This opened the door for any interested company could request concessions on the cancelled lots, placing the territory of the San Miguel del Progreso community in danger.

Júba Wajíin, countered legally and it won an order of protection so that the Secretariat of Economy would leave without effect a declaration of freedom of lands that would permit any company to request mining concessions within the community’s territory. Moreover, the authority was ordered to have prior consultation with the community in these kinds of proceedings. It’s the second protective order that San Miguel del Progreso has won in federal tribunals.

As the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center of La Montaña explains, this is an unprecedented victory, since, for the first time, the secretary was ordered judicially to leave non-existent a declaration of liberty of lands due to violating the collective rights of indigenous peoples.

The indigenous Me’phaa Júba Wajíin community has centuries of roots in that territory. There, since 2011, its 3,800 inhabitants have defended, inch-by-inch, its natural springs, sacred hills, natural resources, climate diversity, fruit trees, coffee plants and its way of earning a living.

Its struggle is exemplary, as much because of its permanence and organization as for the results that it’s harvesting. Among other reasons, because the community was able to see that the promises of development and wellbeing sold by authorities of the Agrarian Prosecutor’s Office in 2011 so that they would accept the exploitation of their territory, were no more than mere glass beads.

The arguments that the community offers for rejecting the dispossession of its territory are profound. According to Valerio Mauro Amado, its commissioner of communal wealth, “we don’t want the mining companies to enter our territory for any reason, because the water is born there, our sacred places are there and we maintain ourselves from our lands” (https://goo.gl/JKJJ3w).

Anastasio Basurto, San Miguel del Progreso’s commissioner when the resistance began in 2011, explained to the journalist Vania Pigeonutt: “The mining companies are not going to enter, they are not going to enter, we must give life! We don’t want to be like those towns that are getting sick, that changed their lands and are dying.”

The consistency of opposition to the extractive project is explained by the confluence of three actors. In the first place, by the extraordinary organizing ability and solidarity of the Me’phaa people, who have preserved and reinvented their identity with great vigor. The vitality and extent of their associative fabric is as remarkable as their ability to reach agreements through consensus.

Secondly, by the accompaniment and support of the priest Melitón Santillán, born in Iliatenco, who warned of the risks of open sky mining, because “I cannot remain silent in the face of an injustice that is going to be commit against poor people.”

And, finally, the effective and professional advice from Tlachinollan and its allies since 2010 explains it. Tlachi put at the center of community defense the use of the legal margins available in national international legal instruments, not as a rhetorical device to air in public opinion, but rather as a matter to litigate effectively in the tribunals.

The dispossession and looting of indigenous territories throughout the country, with its cause of repression, exploitation and devastation doesn’t stop. The victory of San Miguel del Progreso is one piece of good news. It shows that native peoples’ resistance was able to beat back the modern plunderers in the heart of darkness.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Tuesday, July 11, 2017

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2017/07/11/opinion/015a2pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

The pro-capitalist “left”

Franco Torres photo.

By: Gustavo Esteva

The openly anti-capitalist posture of the CNI’s initiative has provoked very different reactions. It’s useful to examine them by reflecting on what it means today to be against what capital says and does.

The most common reaction to the initiative considers it irrelevant. It is not seen as a real threat. It provokes indifference woven with scorn and rejection. It is seen as settled that the majority of the people will continue enclosed in the capitalist prison, as much by daily dependencies on the system as by their dreams, still formulated in their breast. The conviction would prevail that, despite all its defects, capitalism is to remain and nothing better has been found; rather, the conviction that the strength and characteristics of the dominant regime makes openly confronting it foolish. Whether or not one has a critical position with respect to capitalism, this indifference leads to seeking some form of accommodation with forces that seem unbeatable. The open struggle against capital, like that of the CNI, would lack viability and would be mere illusory rhetoric and even demagogic.

Those who pretend to place themselves on the left of the ideological spectrum often adopt that posture. Their cynicism is scarcely hidden under the umbrella of realism. Pablo Iglesias, of Podemos, pointed it out without shades: “May they stay with the red flag and leave us in peace. I want to win” (Público, 26/06/15). His position is not far from what the so-called “progressive” governments of Latin America adopt. The Marxist García Linera celebrates dependent capitalism, developmentalist and extractivist from Bolivia because, according to him, the fruit of exploitation is distributed there among the people. Mujica, in Uruguay, would have changed his dream of transforming the world through the good administration of capitalism. To Lula, his policies were “all that the left dreamed should be done” (La Jornada, 3/10/10). “A metallurgy worker –said with pride– he is making the greatest capitalization in the history of capitalism…” (Proceso, 1770, 3/10/10) The Brazilian “left” supported his alliance with businessmen and corporations, as does the Mexican “left” by supporting similar alliances with AMLO, which would only seek, according to his own words, to smooth the sharpest edges of neoliberal capitalism.

An argument along the same lines that seeks to be more subtle considers that, unless anti-capitalism achieves a global majority, which seems impossible in the foreseeable future, it would imply renouncing all the fruits of the scientific and technological advances of human history, which capitalism would have absorbed into its production and would now determine necessities and general desires.

There is before all else a clear awareness of the current danger in the anticapitalist posture. The slide into barbarity is no longer a theoretical disjunctive, like that which Rosa Luxemburg proposed a hundred years ago: it’s an immediate threat, already completed in many parts. Fighting against capital is now an issue of survival, because what it does to the environment puts the human species in danger and what it does to the society and the culture destroys the bases of our coexistence and intensifies all forms of the reigning violence.

The fight against capital demands, before all else, recognizing that our necessities are not an imposition on nature, but rather the fruit of dispossession. What we suffer today is similar to that of the comuneros that need housing, food and jobs when in the beginning of capitalism their means of subsistence was expropriated from them. Our desires already have the form of merchandise. Having won first place globally in the per person consumption of cola drinks means that the thirst of a very wide sector of Mexican society has been given a capitalist form.

Recuperating desires and necessities is a necessary step in the struggle against capital. It’s the step that gave Via Campesina, one of the largest organizations in human history, when it maintained that we must define for ourselves what we eat… and produce it. Recuperating the desire for one’s own food, cultivating it on recuperated land or in the backyard of a rented house in the city, implies breaking with the social relations of capitalism, simultaneously recuperating the means of production and autonomous decision-making ability in a central dimension of subsistence.

The Zapatistas have the highest degree of self-sufficiency in all aspects of daily life, without falling into relationships of capitalist production. They did not renounce buying machetes, bicycles or computers on the capitalist market, in which they also place products to satisfy needs and desires that they define more autonomously all the time. It’s about a realism very different from that practiced above.

Their open and decided struggle against capital recognizes without nuances or reservations that “it lacks what it lacks.” Without prescribing recipes for everyone or taking refuge in any universal doctrine, they insist on the need of organizing ourselves, which in practice means that each one, in their time and their geography, must learn to govern themselves and to construct their world beyond the capitalist prison.

Only like that, not with complicit accommodations, can we avoid the barbarity towards which it’s leading us. And this position, against what the pro-capitalist “left” thinks, continuously extends to common people, sometimes because of the mere struggle for survival under the current storm, and other times in the name of old ideals.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Monday, July 3, 2017

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2017/07/03/opinion/019a1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee

Seven reasons to support the CNI-EZLN proposal

By: Gilberto López y Rivas

Ever since they made public the consensus proposal of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), to integrate an Indigenous Gobierno Council for Mexico, whose spokesperson will be registered as an independent candidate for the 2018 presidential elections, we have given the task of participating in the round tables, conversations and workshops to various adherents to the Sixth Declaration, in order to reflect, analyze, expound, and of course debate this singular political action, in its multiple dimensions, challenges and commitments.

We’re dealing with another of the initiatives that come from the indigenous world, and, in particular, from Zapatismo and its close associates, for the purpose of articulating the resistances from below and to the left in order to confront that storm of civilizational scope that constitutes current capitalist globalization and that is expressed in a re-colonization and war of conquest of territories, natural resources, disposable human beings, destruction of nature, which are leading the human species and known life forms on a course to their possible extinction. That is, the current struggle of the indigenous and non- indigenous peoples goes beyond the worn out and dismissed schemes of left and right content, and is situated in the dichotomous position of being in favor of life or death. Rosa Luxemburg, who didn’t live the nightmare of Nazi-fascism or of the current form of criminal and militarized capitalist accumulation set forth almost a century ago, now the disjunctive of socialism or barbarism.

Within this context, what are some of the reasons to assume the CNI-EZLN proposal as our own?

1. It’s an idea discussed in depth by the Zapatista Maya communities, and afterwards by the more than 40 expressions of the original peoples that make up the CNI. It is not the fruit of a group of notables that think for the rest, but rather the result of horizontal deliberations of innumerable assemblies that analyzed it until reaching its approval under one of the principles of “govern obeying: convince and not conquer. It is not an “occurrence” of a determined person, nor does it have concealed governmental promoters that the institutional left and the anonymity of the social networks seek to “denounce.”

2. The integration of an Indigenous Government Council for Mexico is maintained in several decades of de facto autonomous experiences, in the entire geography of our dejected national territory, which contrast notoriously with the corrupt, illegitimate and discredited governments at all three levels and powers of the “partidocracy” that have produced a fed up citizenry and a profound crisis of so-called representative democracy. It’s evident that the group currently in power does not represent the interests of the people and of the Mexican nation, and yield governments of national betrayal that have renounced the exercise of sovereignty, and have delivered the country, its territory, labor force and natural and strategic resources to the transnational capitalist corporations, and have docilely submitted to the economic, political, ideological and military domination of the US, the hegemonic armed branch of global imperialism. The Indigenous Government Council and what results from it, is the embryo of popular representation and national sovereignty, starting from what Article 39 of the Constitution, still in effect, establishes.

3. The Indigenous Government Council and the independent candidacy of Compañera María del Jesús Patricio Martínez come from the sector of the exploited, oppressed and discriminated against that has for decades forged a strategy of resistance against capitalism. The autonomy that it institutes is, at the same time, a practice of government and doing politics radically different than what we know, without bureaucracies, intermediaries, professional politicians and caudillos. Despite the structural precariousness, the counterinsurgency war of attrition, the paramilitaries, organized crime, repression and criminalization of their struggles, these self-governments have shown their ability to organize the peoples in a process of reconstitution, awareness, participation of women and youth, strengthening of ethnic-cultural, national and class identities, through the collective and autonomous appropriation of community security, imparting of justice, health, education, culture, communication and economic and productive activities, as well as the defense of territory and its natural resources.

4. In a country in which the corruption and generalized cynicism of the political class rule, indigenous proposal is founded on the notable ethical congruency of its postulants. The EZLN as well as the CNI have practiced what they preach for decades, and have made the principles of not selling out, not giving up, not betraying, not supplanting or taking advantage of other peoples’ struggles a reality. The “for everyone everything, for us nothing,” is a reality throughout all these years. These organizations have been establishing the popular power of govern obeying, without asking anything in exchange and, despite the difficult living conditions, they have been in solidarity with all the struggles of those below.

5. The candidacy of an indigenous woman goes beyond a politics of quotas and feminist positions that don’t take into account the triple oppression that indigenous women have suffered and the cultural specificity in which they demand full rights. It is situated as a clear response to the reigning patriarchy, from a new face gender politics, whose origin we find in the EZLN’s Revolutionary Law of Women.

6. It’s a proposal inclusive, not only of the indigenous and with the indigenous, which makes the vindications of all the exploited, oppressed and discriminated of the earth its own, regardless of their ethnic or national origins and cultural characteristics. It’s not an essentialist or ethnic proposal. The proposal addresses all the peoples of Mexico, including the one of the majority nationality, that world where we all fit.

7. The initiative does not divide the partisan left; as Paulina Fernández points out, it places it on exhibit, and she would add, in all its racism and wretchedness.

————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Friday, June 30, 2017

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2017/06/30/opinion/017a1pol

Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee