Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Indigenous Zapatista Supporter Murdered in Chiapas

ASSASSINATE YOUNG INDIGENOUS LEADER IN CHILON, CHIAPAS

By: Hermann Bellinghausen, Envoy

San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, March 22, 2014

Juan Carlos Gómez Silvano, adherent to the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle from Chilón municipality, was assassinated this Friday on a dirt road in the same location. According to versions picked up by La Jornada, the indigenous man received at least 20 shots.

Koman Ilel, an alternative media of this city, pointed out that Gómez Silvano, a 21-year old Tzeltal campesino, “participated in the construction of autonomy on land recuperated from the Virgen de Dolores plot” in the municipality and was the regional coordinator of the Sixth Declaration, convoked by the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, its initials in Spanish). His community is organized in resistance with the San Sebastián Bachajón ejido.

According to the local press, Gómez Silvano was allegedly traveling alone in a small Nissan farm truck. His body was found at the Chapapujil crossing, near the municipal capital of Chilón. According to “unofficial” versions of the state’s judicial authorities, the Public Ministry agent Octavio Bautista Martínez arrived at the crime scene to pick up the body of the young indigenous leader, but a large group “of masked people” had taken it away “to bury it.”

For its part, Koman Ilel remembers that less than a year ago Juan Vázquez Guzmán, a leader of the Sixth from San Sebastián Bachajón, was executed, also in the capital of Chilón. “Why do they murder them?” the informative note asks, and exposes that the San Sebastián Bachajón ejido “has maintained a strong struggle against the dispossession of its territory for years.”

It points out that: “different actors, among which are found the municipal, state and federal governments; transnational companies (Norton Consulting) and paramilitary groups impel legal and illegal strategies for accomplishing one of the region’s most ambitious projects, part of the Plan Puebla-Panamá: the Palenque Integrally Planned Center, a network of infrastructure and services that seeks to join together natural and archaeological attractions for an elite tourism,” converting the indigenous population “into servants,” in their own communities.

One of the government strategies for securing territorial control, adds the information from Koman Ilel, “has been the cooptation or intimidation of ejido authorities, as well as legal persecution and selective murders of those that are opposed to being dispossessed, as is the case with the compañeros Juan Carlos Gómez Silvano and Juan Vázquez Guzmán.”

The Green Ecologist Party of Mexico currently governs both Chilón and Chiapas. The authorities have been complicit or remiss, at least, faced with the aggressions systematically suffered by the ejido owners in resistance. Mayor Rafael Guirao Aguilar, for sure, also presides over the state’s Green Chiapas Foundation, which supports his fellow party member Governor Manuel Velasco Coello.

—————————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Sunday, March 23, 2014

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/03/23/politica/017n1pol

Indigenous Peoples from 5 Mesoamerican Countries Form Front Against Mining

AGAINST THE IMPERIALISM AND NEOCOLONIALISM OF MINING COMPANIES, THE CURRENT BATTLE OF THE PEOPLES

** Organization is required to win, NGO’s from several countries point out in Puebla

** Emissaries from Mexico, Panama, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador expose abuses of transnationals

By: Rosa Rojas

Tlamanca, Puebla, March 15, 2014

The struggle against extractive mining “it’s not only for our life, but also an anti-imperialist struggle and against neo-colonialism that is imposed on the peoples with the servile attitude of the neoliberal governments and the agreements on free trade and on protection for foreign investment,” according to what was made clear here today after the exposure of particular cases of problems with mining companies that communities from different states of the country confront, as well as those in Panama, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

It was also clear that to make a front against this “fourth colonization,” organization of the peoples is necessary, their taking of consciousness about what environmental destruction means, which is at the same time the basis for sustaining their life; and mobilization and unity in local, regional, national and international action, because we’re battling “against a monster” multi-formed, transnational, which when it suffers a defeat in any place changes for social reasons, even its nationality –a Mexican mining company sells its concession to a Canadian one, which in turn transfers it to an Australian one– without changing its essence: the rapacity of capital.

The Encuentro of Peoples Against the Extractive Mining Model was organized by the Communities in defense of land and life, the Tiyat Tlalli Council, the Mexican Network of Those Affected by Mining, the Mesoamerican Movement Against the Extractive Mining Model, the Center of Studies for Rural Development (Cesder, its initials in Spanish) and the School of Economics of the Autonomous University of Puebla. This Saturday, representatives of the organizations and nations cited above, environmentalists, indigenous peoples and campesinos from Morelos, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Puebla, Guanajuato, and Guerrero and of the Wirrarika (Huichol) people of Jalisco, Nayarit, Durango, Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí (that are only one people, despite the state borders) paraded to the podium.

In some cases, like in Carrizalillo, Guerrero –in the High Mountains of that state–, the battle has already lasted for eight years and the damages to the population’s health and to the environment caused by the Canadian mining company Gold Corporation are manifested in skin and bronchial diseases, congenital deformities, premature births that spill over into the death of 68 percent of those born prematurely, destruction of 11 of the town’s natural springs due to the explosions that the mining company carries out, use and contamination of millions of liters of water per day, and all of that topped of with the cherry of the Federal Prosecutor for Environmental Protection’s (Profepa) “clean industry” certification to the mining company.

In other cases, one of the participants explained, like in El Huizache, in the sierra of Lobos, Guanajuato, the fight is barely beginning; although the exploration work has been advancing, contracting some of the zone’s small property owners that are happy to have work in a place where agriculture is not prodigious, but they have become alarmed because of what they see coming if the concession delivered for an open slash deposit is put into effect. There is a mining tradition in the state –but underground–, thus many people don’t understand the alarm that the new type of industrial mining that approaches has awakened.

Omayra Silvera, of the Coordinator for the Defense of Natural Resources from the Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, of Panama, reported that she comes from an indigenous people that “have made the government tremble” with their mobilizations of more than 6,000 people, including the Inter-American Highway blockage, from border to border, from February 1 to 5, 2012, whose government repression left two dead, hundreds injured, prisoners, and women raped, but the support from international organizations of women, churches and university members “obliged the government to sit down at the negotiating table.”

Said dialogue, she said, resulted in winning the expediting of a special law on the part of the Panamanian Congreso, on March 26, 2012, which cancelled 25 mining concessions and 147 hydroelectric dams that had been granted on indigenous territory of the Ngäbe Buglé, which encompasses 6,968 square kilometers. But the struggle isn’t going to end there, “we are still at the brink of war because they published that a company is going to enter to exploit the Cerro Colorado (Red Hill),” which is one of the largest copper deposits in the world, “because if we remain with our arms crossed, who is going to listen to us?” Omayra asked, in the midst of an ovation from the attendees.

Hermila Navarrete, from El Salvador, related that since 2005 they have not let the Canadian mining company Pacific Ring enter, and that the struggle of the Association of Friends of San Isidro Cabañas led to the government of Mauricio Funes, of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, to expedite a decree that promises that there will be no mining concessions in its administration, which has accepted a complaint before the International Center for Settlement of Differences Relative to Investments for more than 300 million dollars, and the threat of the United States government no to deliver part of the Millennium Funds.

The mine in question, El Dorado, Navarrete indicated, is for gold, silver and uranium. The capital is no longer Canadian, but rather Australian, since Oceana Gold bought the concession.

The representative of the Maya people of Guatemala mentioned that in this “fourth colonization” that our peoples confront, “Guatemala, like Mexico and Central America, is conceded” to transnationals, and that his organization has given birth to “a peaceful struggle of prevention,” promoting more than 80 consultations with the peoples, with many other municipalities; in other words, close to a million people have been consulted that have said “no to mining.”

He also pointed out that as part of the resistance struggle town councils have been constituted in all of western Guatemala, and there are more than 3,000 centers of resistance and struggle in the country, which has cost them “legal cases, criminalization, political prisoners, deaths…” He reported that a few days ago the Chuj, Acateco, Cojtí Plurinational Government was constituted, and on a national scale they have the Council of Huitzilense Peoples and they are part of the Mesoamerican Movement Against Extractive Mining.

Juan Almendarez, from the Mother Earth Movement of Honduras, emphasized that the struggle against extractive mining is anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist and geostrategic, because in his country “mining has never been separated from the Army and police.”

—————————————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Sunday, March 16, 2014

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/03/16/politica/010n1pol

Ostula: Autonomy, Self-Defense, Natural Resources and Narcos

The community recuperation of Xayakalan on the Michoacán Coast is about their lands, guards and autonomy

All kinds of interests cross each other within their territory: the governments seek to implement highway projects that facilitate the shipment of merchandise and stimulate tourism at the beaches; the mining companies want to exploit the vein that originates in San Miguel de Aquila; the small property owners want to plant their lands or subdivide and sell them; and, the drug traffickers have an important point for circulation of their merchandise here.

By: Adazahira Chávez

Organization of the Nahua community of Santa María Ostula, Michoacán, in its struggle for land, was renewed in February of this year. Later, in June 2009, the comuneros activated their Policía Community Police and took back the place known as La Canaguancera (renamed Xayakalan). They confronted a wave of murders and disappearances —especially against members of the traditional guard of the communal wealth (commission)— that established a climate of terror and obliged the displacement of entire families.

But they are returning now and, as they declared in 2009, assert that they will not abandon their lands. Recently, accompanied by self-defense groups from Tierra Caliente, the community guards re-entered their territory —many of them, like their commander Semeí Verdía, were exiled— and the displaced comuneros also returned to Xayakalan, which continues in a legal dispute with the small property owners of La Placita, who invaded it four decades ago. The urgent task, they point out, is to construct the assemblies and to work the lands that gave them sustenance and that they had to abandon.

The task does not look easy, and the Nahuas know it. They tell that all kinds of interests cross each other within their territory: the governments seek to implement highway projects that will facilitate the shipment of merchandise and stimulate beach tourism; the mining companies want to exploit the vein that is born from San Miguel Aquila; the small property owners want to plant their lands or subdivide and sell them; and the drug traffickers have an important circulation point here for their merchandise. In this state —according to the denunciations that the comuneros have made for years— many times these actors are the same subjects. And the comuneros of Ostula are the owners of this coveted land.

Rich land, dispossessed [stolen] land

The communal capital de Ostula and its 22 administrative districts encompass more than 28,000 hectares (approximately 69,000 acres) of Aquila Municipality, one of those of greatest marginalization in Michoacán. The Nahuas have populated the portion of their territory that extends to the Michoacán Coast little by little.

The lands corresponding to the district of Xayakalan, the comuneros report, are located inside of their land titles that in the 18th Century were the very first and also inside of the Presidential Resolution that recognized part of its territory in 1964. Despite that, they confront agrarian litigation over some 700 hectares that six small property owners of La Placita invaded “not only for the planting of papaya, mango and tamarind, but also to sell it to the highest bidder” in spite of precautionary measures in favor of the indigenous. The Commission for the Defense of the Communal Wealth of Ostula points out that some of those invaders are heads of organized crime in the region.

Aquila’s land has an abundance of minerals (silver, zinc, gold and copper), besides iron deposits, which the Ternium, Sicartsa and Metal Steel companies currently exploit, and it contributes one fourth of the national production. The vein that runs through San Miguel Aquila —a community from which members of the traditional guard and the comuneros also had to leave due to conflicts with the mine and with organized crime— arrives in the lands of Ostula, and the Argentine company Ternium has in sight its future exploitation. Ternium is the owner of half of Peña Colorada, the mine in Ayotitlán, Jalisco, which has also provoked persecutions against leaders of the Nahua comuneros like Gaudencio Mancilla.

Inside of this invaded territory pass not only the rich mineral veins, but there are also beaches with animal species in danger of extinction. There, they contemplate the expansion of the Coahuayana-Lázaro Cárdenas Highway, and even the construction of a port for transporting the materials that Ternium extracts from San Miguel Aquila.

On June 13 and 14, 2009, the National Indigenous Congress published the Ostula Manifesto, which vindicated the right to self-defense. After several fruitless attempts at negotiation and upon feeling mocked by the government, the comuneros took back the lands of Xayakalan in 2009, established their community guard “to care for the territory that belongs to us” and around 250 people, belonging to 40 families, settled here.

Los comuneros decided not to participate in the 2011 official (national) elections, just like their Purépecha brothers of Cherán, Pómaro and Coíre, in rejection of the authorities’ lack of efficiency and the divisionism that, they denounced, the political parties promote.

The response to their challenge was deafening. In the last three years, 32 residents of Ostula were brutally murdered or disappeared. The executions in 2011 of the leaders Trinidad de la Cruz Crisóstomo, known as don Trino or el Trompas, in charge of the community guard, and of Pedro Leyva stand out. The Navy bases —that were established after 2009— did not help to stop the wave of violence. Judicial authorities did not resolve even one single crime. Bullets from the “goat horns” (AK- 47s) populated the crime scenes, and the threatened families fled.

Few residents stayed in Xayakalan, but those displaced occupied themselves with planning their return and the reconstitution of their autonomous organization, which was concretized this 2014. On February 8, “a group of comuneros of Santa María Ostula, in coordination with self-defense groups from the municipalities of Coalcomán, Chinicuila and from the capital of Aquila, took control of the tenancy of Ostula,” they reported in a public document.

Coincidentally, since that day “groups of federal ministerial police and members from the public ministry, in a totally illegal way, have been threatening the comuneros that live in Xayakalan with evicting them.” For the indigenous it is “the continuation of the grave conditions of an undeclared war that Ostula has lived through precisely since it resolved to guard the lands of Xayakalan, on June 29, 2009.”

This February 10, a federal Army platoon attempted to disarm the community guard and the self-defense groups that were supporting them, but residents made the soldiers return the weapons. On February 13, more than 1200 comuneros in an assembly decided to formally reorganize the Community Police. Now, efforts are centered on strengthening community decision mechanisms, reconstructing the material base for their organization and survival —food and scarce resources— and on maintaining security within their territory. Despite the years of terror, they indicate to Ojarasca from Ostula, “the people respond to their ancestral organization.”

——————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by Ojarasca #203

La Jornada Supplement, March 2014

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/03/08/oja-costa.html

The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magon – A New Book

Struggles and Contributions are narrated in The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón

** They praise the first transnational network of Mexican and US revolutionaries in a book

** The anthropologist and historian Claudio Lomnitz emphasizes that the theme has current resonance

By: David Brooks, Correspondent

New York, March 10, 2014

The first transnational network of Mexican and US revolutionaries –of which Ricardo Flores Magón formed a part– its participants, its struggle and ideological contributions within the context of the Mexican Revolution are told in the book The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón, from the anthropologist and historian Claudio Lomnitz.

“This is the narration of a transnational revolutionary network that thought of itself as the servant of an ideal. It could be told in the mold of Don Quijote, it is the story of a group of men and women that read books and acted on them, only to confront a society entrenched en its most vulgar preoccupations,” Lomnitz writes in the introduction to the extensive text that explores the political, social and individual dimensions of an extraordinary list of anarchists and socialists of both sides of the border ambos.

Lomnitz, professor of anthropology and director of the Center for Mexican Studies at Columbia University and a La Jornada collaborator, tells how exiles Mexicans came to Texas in 1904, where they began to elaborate plans to impel a revolution in Mexico. “They did not perceive themselves as creators of a new nation, but rather as a regenerative force (…) If they perceived themselves as planting something, it was the seed of revolution (…) For their part, the Americans that worked with these men and women perceived themselves as collaborators in ‘the Mexican cause,’ a movement that had taken the leadership in the universal struggle for emancipation,” he added.

For 1908, two circles –one of Mexicans with Ricardo Flores Magón at the center, almost all anarchists and communists in exile, and the other a circle of US socialists committed to the “Mexican cause”– were linked together around the legal defense of those exiled from Mexico and from there they developed what Lomnitz calls “the first big grass roots US-Mexican solidarity network.”

Ricardo Flores Magón, with his brother Enrique and those around him, are erroneously categorized as “precursors” de la Revolución, Lomnitz writes, and adds that they were contemporaneous with that whole stage. At the same time he points out that the bi-national dimension of that revolutionary network is almost never fully emphasized. The book narrates the experience of Flores Magón and his comrades, among them John Kenneth Turner, Ethel Duffy, Lázaro Gutiérrez de Lara, on both sides of the border before and during the Revolution.

At the New York presentation of the book, professor Renato Rosaldo, of New York University, commented that: “this is a very dangerous book.” He remembers that Flores Magón became a “hero of the Chicano Movement,” just because of his bi-national presence, something that continues having echoes today. “He is a reminder that Mexicans in the United States, the migrants, are not numbers or ants, but rather that they come with very well formed ideologies muy, with political projects and more.” He indicated that Flores Magón was key “in offering a vision of Mexico in and from the United States,” and that he personally suffered repression and persecution on both sides of the border. He emphasized that the text reveals “the role of the US and Mexican revolutionaries in the United States during the Mexican Revolution.”

Professor Arcadio Díaz, of Princeton University, emphasized that the book offers data about the “importance and search for allies” in the bi-national history of the Revolution, the role and particular vision of the anarchists and their devotion to the “worldwide revolution,” as well as the internal conflicts and disputes around this ideal. At the same time, history offers details of, for example, the “complicity of the United States and Mexican governments to spy on and infiltrate the networks” of these revolutionaries. Díaz praised Lomnitz for his exploration of the philosophical debate, the revolutionary practice in exile, the language and culture of the “transnational experience of exile.” He also argued that in some measure this work shows that: “Mexicans and US citizens generated together part of the ideology of the Mexican Revolution.”

Lomnitz explained in the presentation that before the “ideological incoherence of the Mexican Revolution,” manifested in the contradictory poles between Zapatismo, Carrancismo and Villismo, the influence of Magonismo was notable, having emerged from “a movement inside and outside of Mexico,” despite its irrelevance in military terms. The author added that the circle around Flores Magón in the United States was composed of a broad list of revolutionaries with international origins –Irish, Italians, Jewish– who used to sing La Marsellesa in English, Spanish, Italian and Yiddish in their meetings in Los Ángeles.

Lomnitz considered that all of this has current resonance, where a “profound critique of the State” as is expressed in this history, “is what we need today.”

The book was published in English by Zone Books and distributed by MIT Press. The Spanish version will be announced soon.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/03/11/politica/017n1pol

Raúl Zibechi: Reclaiming the Strategic Debate

RECLAIMING THE STRATEGIC DEBATE

By: Raúl Zibechi

It seems evident that we are before a turn of history. What happens in the next few years, added to what is already happening, will have a long-term effect. What we do, or what we stop doing, is going to have some influence on the immediate fate of our societies. We know that it is necessary to act, but it is not clear that we are capable of doing it in the appropriate direction.

The recent events in Ukraine and Venezuela intensified the sensation that we are facing decisive moments. This juncture reveals that violence will play a decisive role in the definition of our future: war between states, struggle between classes, violent conflicts between the most diverse groups, from gangs to drug trafficking organizations. As happened in other periods of history, violence starts to decide junctures and crises.

Violence is not the solution, and the longer we are able to postpone it the better. “Without violence we will not be able to achieve anything. But violence, as very therapeutic and efficient as it may be, does not resolve anything,” Immanuel Wallerstein wrote in the preface of Frantz Fanon’s book Black Skin, White Masks. Being prepared for violence, but subordinating it to the objective of social change, is part of the necessary strategic debates. (Emphasis added.)

I mention the question of violence because of what’s happening in Venezuela and the Ukraine, in Bosnia, South Sudan, Syria and more places all the time. Like it or not, the conflicts are not being resolved in voting booths, but rather in the streets and in the barricades, by means of insurrectional arts that the right is learning to use for its purposes, supported by the big Western powers, the United States and France in an emphatic place. What’s called democracy languishes and tends to disappear.

I never tire of reading and reproducing the view that the journalist Rafael Poch sent from Kiev’s Maidán Square: “In its most massive moments some 70,000 people have congregated in this city of 4 million residents. There is a minority among them of several thousand, perhaps four or five thousand, equipped with helmets, rods, shields and bats for confronting the police. And inside of that collective there is a hard core of perhaps 1,000 or 1,500 purely paramilitary people, disposed to die and to kill, which represent another category. This hard core has made use of firearms” (La Vanguardia, 2/25/14).

Multitudes protesting and small decided and organized nuclei confronting state apparatuses that usually lose all restraint. They succeed for three reasons: because there are tens of thousands in the streets that represent the sentiment of a part of the society, which legitimizes the protest; because there is a “vanguard” often trained and financed from the outside; and because the regime is not in any condition to repress them, either because of weakness, a lack of conviction or because it has no plan for the following day.

That the right may have photocopied the revolutionaries’ ways of doing things and uses them for their own ends, and that they count on abundant support from imperialism, doesn’t make the central question: how to confront situations in which the State is overwhelmed, neutralized or used against those from below?

My first hypothesis is that the anti-systemic forces are not prepared to act without the state umbrellas. Almost all of the continent’s progressive governments were possible thanks to direct action in the streets, paying a high price for putting one’s body on the line, but that dynamic remains very far away and is no longer the patrimony of the movements. Putting one’s body on the line stopped being the common feeling of protest ever since the state shield reappeared with the progressive governments.

The second is that confidence in the State paralyzes and morally disarms anti-systemic forces. To my way of seeing, the worst consequence of this confidence is that we have disarmed our old strategies. This point has two sides: on the one hand, it’s not clear what kind of world we’re struggling for, when state socialism stopped being a projection for the future. On the other hand, because it is not up for debate whether we affiliate with the insurrectional thesis or the prolonged popular war, in other words the European and Third World types of revolution.

I don’t want to linger on the electoral question because I do not consider it a strategy for changing the world, not even a way of accumulating forces. I understand that there are better and worse governments, but we cannot take the electoral path seriously as a revolutionary strategy. In sum, we are not debating the how. Meanwhile, the right does have strategies, in which the electoral plays a decorative role.

Between insurrection and popular war, Zapatismo inaugurates a new path, which combines the construction of non-State powers defended by the communities and support bases with weapons in hand, with the construction of a new and different world in the territories that those powers control.

It can be argued that we’re dealing with a variable of the popular war sketched by Mao and Ho Chi Minh. I don’t see it that way, beyond some formal similarity. I believe that the radical innovation of Zapatismo cannot be comprehended without assimilating the rich experience of the indigenous movement and of feminism, on a crucial point: they do not struggle for hegemony, they do not want to impose their ways of doing. They just act; and the rest decide whether or not to accompany them.

There is a trap in this argument. One cannot “struggle for hegemony” because it would be transmuting it into domination, something that the triumphant revolutions quickly forgot. Hegemony is attained “naturally,” to use a term related to Marx: by contagion, empathy or resonance, with ways of doing that convince, create and enthuse. It seems to me that reclaiming the strategic debate is more important for changing the world than the endless denunciations against imperialism. It’s still necessary to sign manifestos, but it’s not enough.

————————————————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Friday, March 7, 2014

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/03/07/opinion/025a1pol

Venezuela: Cubs of Reaction

Luis Hernández Navarro speaks out on Venezuela

Venezuela: cubs of reaction

By: Luis Hernández Navarro

Lorent Saleh is a 25-year old Venezuelan youth, with flaming language, who studied foreign trade. He is one of the visible heads of the coalition that seeks to overthrow President Nicolás Maduro. He directs Operación Libertad (Operation Freedom) organization, which locates Cuban Castro-communism as the principal enemy of Venezuela.

Lorent began his task against the Bolivarian Revolution in 2007. Since then he has not let up. He organizes hunger strikes that campaigns as Chávez lies. Although he abandoned the classroom years ago, he still introduces himself as a student leader. And, although he has no known employment, he travels around Latin America to try to isolate the Maduro government.

The young Saleh has good friends in diverse countries. In Colombia, for example, the Nationalist Alliance for Freedom and Third Force, neo-Nazi groupings, protect and promote him (El Espectador, 21/7/13).

Vanessa Eisig is a pleasant 22-year old blond woman, who wears glasses and describes herself on her Twitter account as a “warrior for light and bigamous, married to my career and to Venezuela.” She studies communications in the Andrés Bello University and confesses that, by participating in the protests, she feels that she makes history.

Vanessa is a member of United Active Venezuela Youth (JAVU, its initials in Spanish). It demands “the removal of the usurper Nicolás Maduro and all of his cabinet.” The organization has a white right fist as its emblem, which –the young woman says– “is a sign of resistance and of mockery at socialism.”

JAVU, which impels the Operation Freedom initiative, has performed a relevant role in the current disturbances that take place in Venezuela. Founded in 2007, the organization defines itself as a youth resistance platform, which seeks to overthrow “the pillars that sustain a government that scorns the Constitution, wounds our rights and delivers our sovereignty to the orders of the decrepit Castro brothers.”

In its comunicado of February 22 of this year, JAVU denounced that: “foreign forces have militarily besieged Venezuela. Their mercenaries attack us in a vile and savage way. Their objective is to enslave us.” Getting their freedom, they point out, is vital “defending the nation’s sovereignty, expelling the Cuban communists that are usurping the government and the Armed Forces.”

JAVU is inspired and has a close relationship with the Otpor, which in Spanish signifies Resistance, and with the Center for the application of non-violent actions and strategies (Canvas). Otpor was a student movement created in Serbia to remove the government of President Slobodan Milosevic in 2000, which received financing from US government agencies. Canvas is the new face of Otpor.

The guru of those groups is the philosopher Gene Sharp, who vindicates “non-violent” action to overthrow governments. Sharpe founded the Albert Einstein Institute, the promoter of the so-called revolutions of colors in countries that are not similar to the interests of NATO and Washington.

Cables distributed by Wikileaks made public that Canvas –present in Venezuela since 2006– elaborated for the opposition of that country a plan of action, in which it proposes that the student groups and “the informal actors are the ones capable of constructing an infrastructure and exploiting their legitimacy” in the struggle against the government of Hugo Chávez.

The relationship between JAVU, Otpor and Canvas is very tight. As Marialvic Olivares, a member of the extreme right group confessed: “the international organizations that are supporting us at this time always have been at our side, not only in questions of protest, but also in questions of formation, and us with them we have always been at their side. We are not ashamed, we are not afraid to say it.”

But the links between the young Venezuelan student leaders and the think tanks and agencies in cooperation with the right go far beyond the alliance with Otpor/Canvas. Different US foundations have openly financed the dissident movement. They have also counted on support from the Partido Popular of Spain and with the youth organization of Silvio Berlusconi in Italy.

It is the case of the young lawyer Yon Goicoechea, a brilliant star of the 2007 protests and that now is studying for a masters degree at Columbia University, after affiliating with the party of Henrique Capriles and abandoning it when they didn’t give him a deputy position. In 2008 he was generously compensated for his commitment to struggle against Hugo Chávez. The Cato Institute awarded him the Milton Friedman Prize for Freedom, a grant of half a million dollars.

Another force that has played a relevant role in the attempt to depose Maduro is the March 13 University Social Movement, a student organization that acts in the University of the Andes. Its more known leader is Nixon Moreno, an old student of political sciences, accused of raping Sofía Aguilar, now a fugitive and exiled in Panama.

Those youths know what they do: promote political destabilization. They receive international financing. They are active members in the ranks of the ultra-right and anti-communism. They are xenophobes. They are linked with Nazi and conservative organizations in several countries. And they march elbow to elbow with politicians of the radical right like Leopoldo López, María Corina Marchado and Antonio Ledezma.

Despite receiving all this support, Lorent Saleh of Operation Freedom, laments: “We are tremendously alone.” They are partly right. They don’t awaken sympathy or solidarity among Latin American youth. To the contrary, they arouse mistrust and repudiation. And it is how the holder of the pen sees them. Their cause has nothing to with the ideas of the 1968 Mexican student-popular movement. Not in vain do the combative Chilean students repudiate them publically. To them, the cubs of reaction are unpresentable.

———————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Tuesday, March 4, 2014

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/03/04/opinion/021a1pol

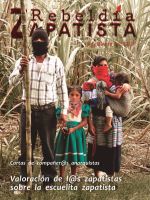

New Zapatista Magazine – Rebeldía Zapatista

New publication: Rebeldía Zapatista: The Voice of the EZLN

MARCH 1, 2014

Editorial by Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés for the first edition of Rebeldía Zapatista, the Word of the EZLN

We rebellious Zapatistas, along with our mother earth, are threatened with destruction in our Mexican homeland. Both above and below the earth’s surface, the bad governments and bad rich people, all neoliberal capitalists, want to commodify everything they see.

They want to own everything.

They are destructive; they are murderers, criminals and rapists. They are cruel and inhuman, they torture and disappear people, and they are corrupt. They are every bad thing you can imagine; they do not care about humanity. They are, in fact, inhuman.

They are few, but they decide everything about how they will dominate countries that let themselves be dominated. They have made underdeveloped countries into their plantations, and made the underdeveloped capitalist so-called governments of those countries into their overseers.

This is what has happened in Mexico. The neoliberal transnational corporations are the bosses, their plantation is called Mexico, the current overseer is named Enrique Peña Nieto, the administrators are Manuel Velasco in Chiapas and the other so-called state governors, and the badly named municipal “presidents” are the foremen.

This is why we rose up against this system at dawn on January 1, 1994.

For 30 years we have been constructing what we think is a better way to live, and what we have built is available for the people of Mexico and of the world to see. It is humble but healthily determined by tens of thousands of men and women who decide together how we want to autonomously govern ourselves.

Nothing hides what we do, what we want, what we seek; it is all in plain sight.

The bad government on the other hand, that is, the three bad powers and the capitalist system, do everything behind the people’s back.

We are sharing our humble idea of the new world that we imagine and desire with compañeros and compañeras from Mexico and all over the world.

That is why we decided to have the Zapatista Little School.

The Little School is about freedom and the construction of a new world different from that of the neoliberal capitalists.

In addition, it is the people themselves, that is, the bases of support, who are sharing these ideas, not just their representatives. These people, not their representatives, are the ones who will say if they are doing well or if the way that they are organized is working well. That way others can see if things are really like the people’s representatives say they are.

This great “sharing” between all of us, compañeros from the city and the countryside, is necessary because we are the ones who must think about how the world we want should be. It can’t just be our representatives or leaders who think about and decide how that world should be, and they certainly can’t be the ones who say how we are doing as an organization. It is the people, the base, who must speak to this.

You can tell us if this has helped those who attended.

As you will read in the writings in this edition of our magazine REBELDÍA ZAPATISTA, this process has helped the compañeros and compañeras who are bases of support to meet good people from other parts of Mexico and all over the world. This is important because in Mexico there is no government that recognizes the indigenous people in this country. The government only remembers them come election time, as if they were electoral paraphernalia.

It is only through organization and struggle that the bases of support have defended themselves for 30 years now.

The bases of support have done everything possible, and everything that seemed impossible, over these 30 years and this is what they are sharing.

We worked to create the Little School so that the words of the compañeras and compañeros who are Zapatista bases of support could reach much further. With the Little School, their voices carry thousands and thousands of kilometers, not like our bullets on January 1, 1994, that only went 50 meters, or 100 meters, and maybe some 300 or 400 meters. The teachings of the Little School cross oceans, borders, and skies to reach you, compañeras, compañeros.

We rebellious indigenous know that there are other indigenous rebellions that also know what neoliberal capitalism is about.

There are also rebellious brothers and sisters who are not indigenous but who write to share in this edition what they think and how they view this system that is destroying planet earth. That is why we include the words of our anarchist compañeras and compañeros in this edition of the magazine.

Well, compañeros of the Sixth, it is good that those who came saw with their own eyes and heard with their own ears what is happening here, and they left ready and willing to communicate this to those who couldn’t come.

In this first edition of the magazine we will begin to share some of the words and ideas of our compañeras and compañeros who are Zapatista bases of support, families, guardians and teachers, about how they viewed the students at the Little School. Throughout the first editions of our publication we will share the evaluations made by the Little School teachers, votanes, families, and coordinators from the zones of the five caracoles.

Just as you have talked about or published what you lived, heard, and saw in our Zapatista territory, here you can read how we saw and heard those who came and raised the flag of ZAPATISTA REBELLION.

Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés

Mexico, January 2014, 20 years since the beginning of the war against oblivion.

——————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by Enlace Zapatista

March 1, 2014

Translated by El Kilombo Intergaláctico

Zapatista News Summary for February 2014

FEBRUARY 2014 ZAPATISTA NEWS SUMMARY

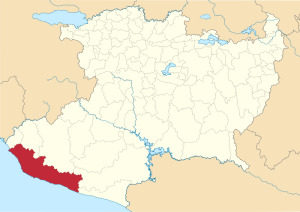

In Chiapas

1. Catholic Nuns Assaulted in Attack on Zapatista Community – During the first two days of February, reports started to come out about a January 30 attack on the Zapatista community of 10 de Abril (April 10th) in which there were serious injuries to several Zapatistas. The aggressors/attackers were from the November 20 ejido in another municipality and called their grouping the CIOAC-Democratic. When 10 de Abril called for medical personnel from the San Carlos Hospital in Altamirano to bring help, the attackers detained the medical personnel and their vehicles, including an ambulance. The aggressors also put their hands all over several nuns in a search for whatever was in their pockets, and ultimately took money and papers out of their pockets. Apparently, the Frayba Human Rights Center notified the Chiapas government of the “urgent” situation and it did nothing. This incident is one of many geared towards dispossessing the Zapatistas of their recuperated land and is part of the “low-intensity” counterinsurgency war. You can read a report here. The national CIOAC organization stated that the aggressors from November 20th are not members of, nor are they affiliated with the national organization.

2. Government Pressure to Privatize Communities in Resistance – Early in February La Jornada issued a series of reports on the northern jungle zone of Chiapas that uncovered government maneuvers used to pressure landholders into privatizing their land. One measure used is to condition Procampo funds on privatization. Procampo is a program that gives cash benefits to peasant farmers. It is funded through the Inter-American Development Bank and designed to offset the negative effects of NAFTA. While many of these communities are in resistance, meaning they do not accept money or programs from the government, there may be a minority living within these same communities that is not in resistance. They DO accept Procampo. Thus, the conditioning of Procampo money on the community agreeing to privatize causes further division within a community. The communities in resistance are supportive of the EZLN in various degrees. Privatizing land is another way to dispossess indigenous communities supportive of the Zapatistas of their land and to foster further political divisions. One report also included an update on the Viejo Velasco Massacre fallout.

3. San José El Porvenir Also Opposes San Cristóbal-Palenque Toll Road – Last month, Los Llanos, a Tzotzil community in the rural part of San Cristóbal de las Casas Municipality, obtained a temporary injunction against construction of the San Cristóbal-Palenque Toll Road until there is a decision on the case. We posted a translation of the news article on our blog. The toll road is one of the infrastructure projects envisioned within the Plan Puebla Panamá (now renamed the Mesoamerica Project). Its purpose is to facilitate tourism. Now, another Tzotzil community affected by the toll road, San José El Porvenir, has announced its opposition to the superhighway and its agreement with Los Llanos. San José El Porvenir is located in the municipality of Huixtán.

4. They Inaugurate Palenque International Airport – On February 12, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto and Chiapas Governor Manuel Velasco Coello attended the inauguration of the Palenque International Airport in Chiapas. The opening of this airport represents the completion of another key infrastructure project of the Mesoamerica Project for facilitating tourism and commerce in the Northern Zone of Chiapas. It is anticipated that the airport will receive the first Interjet flight on March 13. Of interest was a statement from the (federal) assistant secretary of Transportation and Communications, Carlos Almada López, about the Palenque-San Cristóbal Toll Road. Almada said that the preliminary design for the superhighway would be finished in May and that will determine the project’s specific trajectory and timetable. After this inauguration it was revealed that the federal government will provide $18 billion pesos for highway construction in Chiapas in order to further facilitate tourism and commerce.

5. Displaced from the Puebla Ejido Return to Acteal and Land Returned to Church – The people displaced from the Puebla ejido extended their stay in Puebla to harvest their coffee fields until February 6. Members of social organizations continued to accompany them. Although they received insults and threats, the harvest was successful. Many of the 98 displaced individuals are members of Las Abejas of Acteal, an adherent to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration. The displaced have set the following conditions for a permanent return to the Puebla ejido: 1) recognition of the Catholic Church’s ownership of the plot of land in question; 2) recognition and reparations for the damages, to the community for the destruction of work on the church and for the destruction of homes;” and 3) reparations for “personal damages for the robberies and destruction” of personal belongings inside their homes.The land on which the church was being re-built was returned to the Diocese of San Cristóbal de las Casas on February 26.

In other parts of Mexico

1. Amnesty International Human Rights Abuse in Mexico – The Secretary General of Amnesty International (AI), Salil Shetty, visited Mexico from February 15-18. He said that Mexico projected a false image of respect for human rights. While it passes many important laws in that regard, grave human rights violations continue to occur and some of the data even indicate a crisis. Among the grave concerns are the forced disappearances, attacks on journalists and human rights defenders and the abuse of undocumented migrants. What all these violations have in common is the impunity of the perpetrators. He also expressed concern about the self-defense groups (autodefensas). You can read AI’s report “Human Rights Challenges Facing Mexico” here.

2. Santa María Ostula Issues Denunciation And Gets Help From Autodefensas – On February 24, Santa María Ostula posted a comunicado/denunciation on the Enlace Zapatista website. Ostula declared its autonomy in 2009 and is part of the National Indigenous Congress and an adherent to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle. One of the communities the autodefensas visited this month is Santa María Ostula and its village of Xayakalan. According to the denunciation from Santa María Ostula, its residents, together with the autodefensas, took control of Santa María Ostula. Then, on February 10, a Mexican Army platoon entered Ostula and disarmed both the local community police and the autodefensas. The weapons were returned after they convinced the Army that they would be murdered if they were without weapons. 31 members of the autonomous region have been murdered since 2009. On February 13, Santa María Ostula reorganized its community police and, in coordination with the autodefensas, took over the nearby town of La Placita. That is where the people live that murdered the 31 comuneros. The comunicado and several news reports state that some of those living in La Placita are heads of the local drug cartel. The alleged cartel members fled before the community police entered the town. The denunciation states that ever since February 8, federal ministerial police have come to Ostula threatening eviction and it asks national and international civil society to be alert to these threats.

3. Joint DEA and Mexican Navy Operation Nabs El Chapo Guzmán – On February 22, Mexican marines and DEA agents raided an apartment in Mazatlan, Sinaloa, Mexico and took alleged drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera into custody. He has been placed in a maximum security prison. The United States wants him extradited. While much will be made of his capture and imprisonment as a major victory in the Drug War, the reality is that someone will replace him and the drugs will continue to flow. You can read the story of his capture in the Los Angeles Times.

4. Obama Attends North American Summit in Toluca – On February 19, US President Barack Obama attended the North American Summit of NAFTA leaders in Toluca, Mexico. He spent a total of 8 hours in Mexico with the Canadian Prime Minister and the President of Mexico. The visit was expected to be mostly about the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP); in other words, about trade. While some agreements that facilitate trade were reached, the general impression was that Obama was preoccupied with events in the Ukraine and Venezuela.

—————————————————

Resumen De Noticias Zapatistas – Enero 2014

RESUMEN DE NOTICIAS ZAPATISTAS – ENERO 2014

En Chiapas

1. ¡Los zapatistas celebran 20 años de resistencia!.– El primero de enero de 2014, los zapatistas celebraron el 20 aniversario de su rebelión y resistencia. Recibieron aproximadamente 5000 estudiantes durante las dos Escuelitas, una durante la semana antes del primero de enero, y otra la semana después. Los estudiantes de ambas Escuelitas asistieron a la celebración del aniversario, junto con otros simpatizantes que se unieron al festejo. Estamos a la espera del próximo comunicado del EZLN anunciando las fechas de la próxima Escuelita.

2. Ejido en Chiapas interpone amparo contra la autopista San Cristóbal-Palenque.– El 6 de enero, Los Llanos, una comunidad tzotzil ubicada en la zona rural del municipio de San Cristóbal, interpuso una demanda de amparo contra la construcción de la autopista San Cristóbal-Palenque. El 13 de enero, el juzgado admitió el amparo y suspendió los permisos de construcción hasta que se resuelva en definitiva el juicio del amparo. Hemos traducido al inglés un artículo sobre esta noticia y publicado en nuestro blog. La autopista es uno de los proyectos de infraestructura del Plan Puebla Panamá (ahora conocido como Proyecto Mesoamérica) para facilitar el turismo. Los Llanos se ubica al otro lado de la carretera del ejido Mitzitón, que tiene una historia de conflictos y protestas contra la construcción de la autopista.

3. San Sebastián Bachajón (SSB) denuncia que un ex-prisionero no está libre y que ha habido otro intento de desalojo.– Antonio Estrada, residente de San Sebastián Bachajón, fue liberado de la prisión estatal de Chiapas la nochebuena pasada. Sin embargo, tiene que reportarse y registrarse cada semana en el tribunal de la capital del estado. Aparentemente todavía hay un caso federal pendiente contra él por el delito de postración de armas de uso exclusivo del ejército mexicano. El 24 de enero, un tribunal le otorgó a Estrada una orden de protección contra el cargo, lo cual abre la puerta a la posibilidad de absolución por este delito.

Los ejidatarios también acusan a la facción pro-gobierno en el ejido SSB de intentar de fabricar otro acto de asamblea falso para poder despojarles de las tierras en disputa desde el 2011.

4. Los desplazados del Ejido Puebla regresan a cosechar su café.- Del 17 al 27 de Enero, los desplazados del ejido Puebla volvieron a cosechar sus cafetales después de casi 5 meses. Miembros de organizaciones sociales los acompañaban. Aunque recibieron insultos y amenazas, fueron capaces de cosechar sus campos y luego regresar al campamento de refugiados en Acteal. Muchas de las 98 personas desplazadas son miembros de Las Abejas de Acteal, adherentes a la Sexta Declaración del EZLN.

5. El Ejido Tila obtiene orden judicial para detener el despojo de su tierra.-El ejido Tila está situado en la zona norte del estado y es un adherente a la Sexta Declaración de la Selva Lacandona. Una porción de su territorio ejidal se encuentra dentro de la ciudad de Tila, capital del municipio de Tila. Un edificio conocido como “Casino del Pueblo” fue tomado por las autoridades municipales hace algún tiempo y es todavía objeto de litigio que lleva años y aún está pendiente ante la Suprema Corte de justicia de México. Ahora, sin embargo, las autoridades municipales quieren derribarlo para construir allí un centro comercial y, aunque el edificio no es propiedad del municipio, están promoviendo un referéndum sobre el proyecto para utilizarlo como un sustituto del “consentimiento previo, completo e informado” requerido cuando las tierras indígenas son afectadas por el gobierno. El 24 de enero, el ejido Tila obtuvo una orden judicial a favor suspendiendo cualquier actividad de construcción en la propiedad del ejido hasta que se resuelva definitivamente el caso en la corte.

6. Despojo en la Selva Lacandona de Chiapas.- Un periodista de La Jornada recorrió partes de la Selva Lacandona y describió, en diversos reportes, sobre los intentos del gobierno por afectar la tierra en la parte norte de la selva, algunos de estos en la denominada zona de amortiguamiento de la lacandona. Las comunidades de esa región están descontentas con la aplicación de programas gubernamentales como el Fanar (fondo de apoyo a los núcleos agrarios sin registro, anteriormente llamado Procede), que limita el uso de sus tierras y que permitiría la privatización de parcelas individuales. Fanar está siendo promovido por Sedatu (Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano) y también por la Procuraduría agraria.

De otras partes de México

1. El gobierno mexicano legaliza provisionalmente a grupos de autodefensa michoacanos.– El 27 de enero, los grupos de autodefensa michoacanos y el gobierno federal firmaron un acuerdo en el municipio de Tepalcatepec. El acuerdo requiere que las fuerzas de autodefensa sean registrados por nombre, al igual que sus armas por el gobierno y que se incorporen al Cuerpo Mexicano de Defensas Rurales bajo el mando de la Secretaría de Defensa Nacional (SEDENA). El acuerdo se dió después de un mes de enfrentamientos entre los grupos de autodefensa y supuestos integrantes de los cárteles, mientras que el Ejército Mexicano se desplegó masivamente en el estado. A principios del mes, la agencia Reuters dió a conocer que algunos cárteles estaban exportando hierro de las minas a China a través del puerto Lázaro Cárdenas. En cuanto a los grupos de autodefensa, se ha cuestionado frecuentemente de donde proviene su financiamiento. Existen también versiones acerca de que otro cártel, el llamado cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación ha proporcionado algunas de las armas a las autodefensas.

Compilación mensual hecha por el Comité de Apoyo a Chiapas.

Nuestras principales fuentes de información son: La Jornada, Enlace Zapatista y el Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Bartolomé de las Casas (Frayba).

_______________________________________________________

Chiapas Support Committee/Comité de Apoyo a Chiapas

P.O. Box 3421, Oakland, CA 94609

Email: cezmat@igc.org

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Chiapas-Support-Committee-Oakland/