Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Holloway: Critical thinking against the capitalist hydra

CRITICAL THINKING AGAINST THE CAPITALIST HYDRA

By: John Holloway*

Critical thinking: thinking that looks for hope in a world where it doesn’t appear to exist anymore; that opens what is closed, that rattles what is fixed. Critical thinking is the attempt to understand the storm and more. It is to understand that at the center of the storm there is something that gives us hope.

The storm is coming; or better yet it is already here. It is here and it is probably going to intensify. We have a name: Ayotzinapa; Ayotzinapa as horror and also as a symbol of many other horrors, Ayotzinapa as a concentrated expression of the fourth world war.

Where is the storm coming from? Not from the politicians; they are merely the executors of the storm. Not from imperialism, it is not a product of the governments, nor from the most powerful governments. The storm surges from the form in which society is organized. It is an expression of the desperation, the fragility, the weakness of a form of social organization that is already past it’s expiration date, an expression of the crisis of capital.

Capital as such is a constant aggression. It tells us every day “you have to mold what you do in a certain way, the only activity that is valid in this society is the one that contributes to the expansion of capital’s profits.”

The aggression that capital is has a certain dynamic. To survive it has to subordinate our activity every day more intensely to the logic of profit: “today you have to work faster than yesterday, bend over more than yesterday.”

With that we can see capital’s weakness. It depends on us, what we want and accept what it imposes on us. If we say “excuse me, but today I am going to cultivate my plot of land.” or “today I am going to play with my children,” or “today I am going to dedicate time to do something that makes sense for me,” or simply “We are not going to bow down,” then capital cannot extract the profits it needs, the rate of profit falls, capital is in crisis. In other words, we are the crisis of capital, our lack of subordination, our dignity, and our humanity. We are the crisis of capital and proud of being so, we are proud of being the crisis of the system that’s killing us.

Capital despairs of this situation. It looks for all the possible ways to impose the subordination it needs: authoritarianism, violence, labor reforms, educational reforms. It also introduces a game, a fiction; if we cannot extract the profits that we require, we are going to feign that there exists, to create a monetary representation for a value that has not been produced, expand the debt to survive and try to use it at the same time to impose the discipline that is needed. But this fiction increases the instability of capital and additionally it fails to impose the necessary discipline. The dangers for capital that this fictitious expansion represents becomes clear with the collapse of 2008, and with that it becomes more evident that only way out for capital is through authoritarianism: all the negotiation around the Greek debt tells us that there is no possibility for a softer capitalism, that the only path for capital is the path of austerity, of violence; the storm that is already here, the storm that approaches.

We are the crisis of capital, we who say no, we who say: Enough of capitalism!, we who say that it is time to stop creating capital, that there is another way of living.

Capital depends on us, because if we do not create profits (surplus value) directly or indirectly, then capital cannot exist. We create capital, and if capital is in crisis it’s because we are not creating the necessary profits for the existence of capital, that’s why they’re attacking us with so much violence.

In this situation, we really only have two options of struggle. We can say “Yes, we are in agreement that we are going to continue producing capital, promoting the accumulation of capital, but we want better living conditions.” This is the option of the governments and parties of the left: of Syriza, of Podemos, of the governments in Venezuela and Bolivia. The problem is that, even though we can improve our living conditions in some regards, through the desperation of capital itself there is very little possibility of a more humane capitalism.

The other possibility is to say “Good by, capital, leave, we are going to create other ways of living, other ways of being in relationship, among ourselves and also with the non-human forms of life, ways of living that are not determined by money and the search for profits, but through our own collective decisions.”

Here at this seminar we are at the very center of the second option. This is the point of encounter between Zapatistas and Kurds and thousands of more movements that reject capitalism, attempting to construct something different. Everyone of us, women and men are saying “Capital, your time has passed, leave now, we already building something else.” We express in many different ways: We are making cracks in the wall of capital and attempting to promote its confluences, we are building the commons, we are communing, we are the movement of doing against work, we are the movement of use value against value, we are the movement of dignity against a world based on humiliation. We are creating here and now a world made of many worlds.

But, do we have sufficient strength? Do we have enough strength to say that we are not interested in capitalist investment, that we are not interested in capitalist employment? Do we have the strength and force to totally reject our actual dependency on capital to survive? Do we have the strength to say a final “good-bye” to capital?

Possibly, we do not have it, yet. Many of us who are here today have a salary or our grants that come from the accumulation of capital or, if not, we are going to return next week to look for work from a capitalist. Our rejection of capital is a schizophrenic rejection: we want to say a definitive goodbye, and we cannot or it costs us a lot of work. Purity does not exist is this struggle. The struggle to stop creating capital is also a struggle against our dependency on capital. Which is to say, it is a struggle to emancipate our creative capacities, our strength to produce, our productive forces.

We are in it, that’s why we came over here. It is a question of organizing ourselves, clearly, not about creating an organization, but of organizing ourselves in multiple ways to live from now on from the world we want to create.

How do we advance, how do we walk? By asking questions, of course, asking and holding each other and organizing ourselves.

* Post-graduate professor of sociology at the Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. This is the text of a document presented to the Seminar on critical thinking against the capitalist hydra [Seminario sobre el pensamiento crítico frente a la hidra capitalista].

————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Friday, May 15, 2015

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2015/05/15/opinion/018a1pol

La Garrucha denounces paramilitary acts in San Manuel

CARACOL OF RESISTANCE TOWARDS A NEW DAWN

Path of the Future Good Government Junta,* La Garrucha, Chiapas, Mexico

Mural on front of former offices of Good Government Junta in La Garrucha carries the name of the Caracol in both Spanish and Tseltal.

May 11, 2015

WE DENOUNCE PUBLICLY

To public opinion:

To the communications media, alternative, autonomous or whatever you call them:

To the national and international adherents of the Sixth:

To the honest human rights organisms:

Sisters and brothers of the people of Mexico and of the world:

We energetically denounce what the paramilitary groups of Rosario are doing to us. There are 21 paramilitaries in Rosario and 28 paramilitaries from the Chikinival barrio of the Pojkol ejido in the municipio of Chilón, Chiapas.

Our compañero support bases live there in Rosario, because it is recuperated land, belonging to San Manuel autonomous municipio of Caracol III La Garrucha.

There are 21 paramilitaries living in Rosario and they are supported by the 28 paramilitaries from barrio Chikinival that are invading our recuperated land.

It has been the same problem since August 2014, when they killed a stud bull of ours, when they destroyed homes and destroyed our collective cooperative, stole our belongings, when they fumigated a hectare of pasture land with herbicide, when they were shooting and leaving letters in the ground with spent shells that said: “Pojkol territory.” [1]

WHAT HAPPENED

On May 10, 2015, at 9:35 in the morning, 28 arrived people that belong to the Chikinival barrio of the Pojkol ejido in the official municipio of Chilón, some 40 minutes away by car from the town of Rosario. They arrived aboard eight motorcycles, in the recuperated town of ROSARIO where the compañero support bases live, because they want to take our land away by force.

These paramilitaries of Rosario, accompanied by the paramilitaries from the Chikinival barrio of the Pojkol ejido, started to measure the sites where the compañero support bases are already living, during the day they were working there.

At 15:15 pm, a group of them withdrew from working, another group stayed in the same place, but 5 minutes later three of them headed to the home of a support base compañero, and the majority of them stayed on the highway 30 meters from the compañero’s house. They only found the 13-year old daughter of the support base compañero at home sweeping her room, not the father. The mother was outside on one side of the house.

Two of these paramilitary aggressors belong to the Chikinival barrio of the Pojkol ejido and one belongs to Rosario. His name is ANDRES LOPEZ VAZQUEZ. The 2 from Chikinival entered inside of the house, while Andrés, the Rosario paramilitary, stood guard at the door of the house. Upon seeing that the compa’s young daughter went out running for the door, ANDRES shot at her 4 times with a 22-caliber pistol. Her father arrived at the moment of the shots and the compañero defended his daughter, throwing a stone at the attacker that hit him in the head. None of the bullets hit the young woman. His compañeros that were at 30 meters carried the injured man away.

Yesterday afternoon, May 11, the injured man returned the family members of the aggressor went to the compañero’s house, in other words, the wife and 3 sons to say that they have to pay him 7,000 pesos for his care.

It’s clear that the compañero will not pay, because he is not the one who sought and provoked what happened.

On May 10 at 6:50 pm, 16 people arrived in village of Nuevo Paraíso in Francisco Villa the autonomous municipio. Three of them were armed with two 22-caliber pistols in hand and one 22-caliber long arm. They were aboard 8 motorcycles. These people belong to the Chikinival barrio of the Pojkol ejido. They came to throw a letter in the street, wherein they blame the support base compañeros for provoking these problems first.

But in reality we are not the ones provoking any problem, because we have been seeking peaceful alternatives for trying to resolve this matter, but they have never understood us. We have even delivered one hectare to each one of the 21 persons that are provoking, even so they have been threatening us. From February until today, May 11, those from Chikinival in the Pojkol ejido are threatening us daily because they ask those of Rosario to patrol armed. Those from Pojkol are always armed every day.

Therefore, we contradict what they are doing and blaming. It’s clear who provokes first.

We have cited (sent a notice to appear) the Pojkol ejido’s authorities and they came and said that they cannot do anything, because that group is not recognized now in the ejido, because they are totally some hoodlums, they do not respect or obey in the ejido. He also advised that the State of Manuel Velasco Coello also does nothing because it is his paramilitary.

Compañeros and compañeras, brothers and sisters of the world, these are the strategies with which the three levels of bad federal, state and municipal government are provoking us, when they use people that don’t understand our just cause so that that way we fall into their traps; but we are clear about what this bad government is doing: organizing, preparing and financing organizations and people that let themselves be bought off or that sell out.

We say to those without brains up there above: we are never going to stop resisting, not are we going to fall into their traps; we will continue resisting here, working our lands and constructing our autonomy.

Whatever may come to pass, we place responsibility directly on the federal, state and municipal governments and on the paramilitaries from Chikinival barrio of the Pojkol ejido and from Rosario.

Sisters and brothers, we will continue reporting what may happen with our peoples and we want you to remain attentive to what may happen.

SINCERELY,

Good Government Junta

Jacobo Silvano Hernández Lucio Ruiz Pérez

—————————————————————–

* We have translated the name of the Good Government Junta as “Path of the Future” because in that region of the Jungle the word camino is used to refer to one’s current path in life.

[1] For background on what happened last August 2014, see: https://compamanuel.wordpress.com/2014/10/04/anatomy-of-a-paramilitary-attack-on-the-zapatistas/

——————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by Enlace Zapatista

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Monday, May 11, 2015

EZLN renders homage to Luis Villoro and teacher Galeano

The EZLN renders homage to Luis Villoro and to teacher Galeano

By: Isaín Mandujano

OVENTIK, Chiapas (proceso.com.mx) – This Saturday, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, its initials in Spanish) rendered homage to the Mexican philosopher Luis Villoro Toranzo and to the Indigenous Zapatista teacher Galeano, assassinated precisely one year ago in La Realidad, by an anti-Zapatista shock group.

More than five thousand people, between indigenous EZLN support bases and adherents and sympathizers of the movement, gathered in the esplanade to see on the stage the families of Don Luis Villoro, teacher Galeano, the parents of a youth disappeared from Ayotzinapa seven months ago, the General Command of the armed group and the surprising public appearance of Subcomandante Galeano.

Before the event, six columns of Zapatista milicianos with green pants and brown shirts guarded the family members of those being paid homage to from the principal entrance to Oventik for a kilometer until arriving at the enclosure where the ceremony would take place.

Among the fog that covered the development of the entire event, the words of Don Pablo González Casanova were read first. He remembered many of the political differences that he always maintained with Luis Villoro.

On one occasion he dared to say to him: “Do you agree, Luis? We have always had theoretical differences and discussions, but we always find ourselves in the same battle as now with the Zapatistas,” to which Villoro responded: “The solution is not logical, but rather ethical.”

González Casanova eulogized Villoro’s contribution to critical thought in his text sent for the homage, as Adolfo Gilly would do, upon a reading after an extensive speech in which he rescued extracts from his books and essays in which he brought up the domination and liberation of the peoples.

It was Silvia Fernanda Navarro Solares, Villoro’s life-long compañera, who talked about the love and commitment the philosopher had for the Zapatista struggle and cause, for whom he dedicated much of his analysis of social and political theory.

Navarro said that she, as much as Villoro, were always assiduous visitors of the Zapatistas and their communities, so much so that he contributed resources for the construction of the Zapatista School in Oventik.

And that throughout these 21 years they have accompanied the indigenous Zapatista communities in their advances and achievements that since August 2003 made theirs full autonomy to work in matters of education and the development of all of the rebel autonomous peoples.

She eulogized the level of organization and discipline of the Zapatistas that have walked these two decades accompanied above all with other peoples of Mexico and the world that have been in solidarity with the Zapatista cause.

Juan Villoro at his turn pointed out that it was the Zapatistas that put into the national public arena the fraternal struggle of the masked ones that is not annihilating, but rather transforming.

In the name of his three absent siblings, Miguel, Carmen and Renata, he thanked the Zapatistas for the homage to his father that they organized in this Caracol, one of the seats of the five Good Government Juntas.

He said that his father hated homages and with all certainty would have been opposed to this event that the rebels organized, but in his absence he can’t do anything now, he said, to the complicit laugh from the crowd.

After Juan Villoro’s speech, Subcomandante Galeano suddenly appeared from among the masked indigenous peoples, where he had remained camouflaged the whole time, to read an extensive discourse that the “dead Marcos” wrote after his death in March 2014, a homage that he would have made in the middle of last year, but that had to be suspended because of the attack and the death of Galeano.

Galeano, who “buried” Marcos on May 25, 2014 after taking the name of the fallen Zapatista teacher, he revealed today to the family members present, that the philosopher Luis Villoro Toranzo was “a Zapatista compañero” that after a night and early morning in May many years ago he came out as a member of the EZLN with the condition that no one, not even his own family, would know about it.

He indicated that UNAM’s professor of philosophy, Don Luis Villoro was a Zapatista not only until his death but also as of now that he is remembered for his commitment as a sentinel that fulfilled the mission with which he was charged.

When they asked him then what his clandestine name would be, Don Luis Villoro elected his real name, which surprised the Zapatistas, but he assured what that would precisely do: it would hide the Zapatista with the role of a philosopher that the whole world already knew. Well then, nobody would know that Villoro would have really been an EZLN member.

He says that instead of a mask, Don Luis Villoro would always wear a black beret, to camouflage his identity. The first mission to which he was assigned was like that of everyone when they started in the ranks of the EZLN; he did the “post,” standing guard, because of which he was always a “Zapatista Sentinel,” which mission he knew how to fulfill until his last days.

Galeano reviewed that meeting with the Zapatista philosopher that even left his chestnut brown jacket hanging in the EZLN Barracks at which he presented himself to leave as one more in the ranks of the armed group.

After thanking the presence of the family members of Don Luis Villoro, he reviewed the life and trajectory of teacher Galeano in the ranks of the EZLN, who got to know the Zapatista guerillas in 1989. Little by little he was enrolled to be a miliciano that participated in the January 1, 1994 feat under the command of Insurgent Captain Zeta, in the taking of Las Margaritas, where the most affectionate Subcomandante Pedro would be killed with bullets.

Galeano said that the Zapatista teacher from whom he took his new name was a rebel, and that he also fulfilled all the missions to which he was assigned. Because of that and nothing less than that they have presented this deserved homage.

His daughter Lizbeth was there, as well as his son Mariano, his wife Selena and his father Manolo, who talked about Galeano, the teacher at the Escuelitas Zapatistas that the EZLN had organized months before to the thousands of adherents that came from diverse communities of the five autonomous regions where they have a presence.

Upon the event ending, those with ski masks sung the Zapatista Hymn and the milicianos broke ranks in order to protect the exit of the EZLN’s general command and SupGaleano.

Fernanda Navarro was moved; she thanked the homage with tears. Juan Villoro also said that his father would not have imagined this multitude of masked indigenous rebels that today rendered homage to him today for his support to critical thinking and for his unconditional support to the EZLN’s cause.

This Sunday, the family of Villoro Toranzo will deliver the philosopher’s ashes to the Zapatistas so that he may be buried in the shade of a luxuriant tree as was his wish, to finally rest in the territory to which he dedicated his last 20 years of life.

——————————————————————

Originally Published in Spanish by Proceso.com.mx

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Sunday, May 3, 2015

En español: http://www.proceso.com.mx/?p=403142

EZLN: Program and other information about the homage and seminar

PROGRAM AND OTHER INFORMATION ABOUT THE HOMAGE AND THE SEMINAR

ZAPATISTA NATIONAL LIBERATION ARMY

MEXICO

April 29, 2015

Compas:

Here is the latest information about the May 2, 2015 celebration in Homage to compañeros Luis Villoro Toranzo and Zapatista Teacher Galeano, and the seminar that will be held from May 3-9, 2015.

First.- A group of graphic artists will also participate in the Seminar: “Critical Thought Versus the Capitalist Hydra,” with an exposition called “Signs and Signals” of their own works of art made especially for this exposition. The following people will participate:

| Antonio GritónAntonio Ramírez

Beatriz Canfield Carolina Kerlow César Martínez Cisco Jiménez Demián Flores Domi Eduardo Abaroa Efraín Herrera Emiliano Ortega Rousset Felipe Eherenberg Gabriel Macotela |

Gabriela Gutiérrez OvalleGustavo Monroy

Héctor Quiñones Jacobo Ramírez Johannes Lara Joselyn Nieto Julián Madero Marisa Cornejo Mauricio Gómez Morín Néstor Quiñones Oscar Ratto Vicente Rojo Vicente Rojo Cama |

The opening of the exposition will take place Monday morning, May 4, 2015, in CIDECI.

SECOND. Here is the program of activities and participants for the seminar. There may be some changes (note: all hours listed are “national time”).

HOMAGE:

Saturday, May 2. Caracol of Oventik. 12:30.

Homage to compañeros Luis Villoro Toranzo and Zapatista Teacher Galeano.

Participants:

Pablo González Casanova (written statement).

Adolfo Gilly.

Fernanda Navarro.

Juan Villoro.

Mother, father, wife and children of the compañero teacher Galeano.

Compañero teacher Galeano’s compañeros and compañeras in struggle

General Command – Sixth commission of the EZLN.

Note: On May 2, the caracol will be open for entry before 12:30. At 12:30, you will be asked to gather outside the caracol in order to begin the welcome ceremony for the families of those to whom we are paying homage and for the guests of honor, and you can then follow them to the specific place where the homage will be held. After the event, you will need to leave the caracol because it will be completely filled by the compañeras and compañeros who are bases of support. You will not be able to spend the night at the caracol. We estimate that the homage will end between 4 and 5 in the afternoon at the latest, so you will be able to return safely and comfortably to San Cristóbal de las Casas.

SEMINAR “CRITICAL THOUGHT VERSUS THE CAPITALIST HYDRA”

Sunday, May 3. Caracol of Oventik. 1000-1400 hrs. We ask that you arrive a little bit before the start time.

Inauguration by the General Command of the EZLN.

Don Mario González and Doña Hilda Hernández (video participation).

Doña Bertha Nava and Don Tomás Ramírez.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Juan Villoro.

Adolfo Gilly.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Relocate to the grounds of CIDECI in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, beginning at 1400 hours.

Sunday, May 3 CIDECI. 1800 – 2100 hrs.

Sergio Rodríguez Lazcano.

Luis Lozano Arredondo.

Rosa Albina Garavito.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Monday, May 4, CIDECI. 1000 – 1400 hrs.

María O’Higgins.

Oscar Chávez (recorded message).

Guillermo Velázquez (recorded message).

Antonio Gritón. Opening of the Graphic Exposition “The Capitalist Hydra”

Efraín Herrera.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Monday, May 4, CIDECI. 1700 – 2100 hrs.

Eduardo Almeida.

Vilma Almendra.

María Eugenia Sánchez.

Alicia Castellanos.

Greg Ruggiero (written message).

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Tuesday, May 5, CIDECI. 1000 – 1400.

Jerónimo Díaz.

Rubén Trejo.

Cati Marielle.

Álvaro Salgado.

Elena Álvarez-Buylla.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Tuesday, May 5, CIDECI. 1700 – 2100.

Pablo Reyna.

Malú Huacuja del Toro (written message).

Javier Hernández Alpízar.

Tamerantong (video participation).

Ana Lidya Flores.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Wednesday, May 6, CIDECI. 1000 – 1400.

Gilberto López y Rivas.

Immanuel Wallerstein (written message).

Michael Lowy (written message).

Salvador Castañeda O´Connor.

Pablo González Casanova (written message).

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Wednesday, May 6, CIDECI. 1700 – 2100.

Karla Quiñonez (written message).

Mariana Favela.

Silvia Federici (written message).

Márgara Millán.

Sylvia Marcos.

Havin Güneser, from the Kurdish Freedom Movement.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Thursday, May 7, CIDECI. 1000 – 1400.

Juan Wahren.

Arturo Anguiano.

Paulina Fernández.

Marcos Roitman (written message).

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Thursday, May 7, CIDECI. 1700 – 2100.

Daniel Inclán.

Manuel Rozental.

Abdullah Öcalan, of the Kurdish Freedom Movement (written message).

John Holloway.

Gustavo Esteva.

Sergio Tischler.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Friday, May 8. CIDECI. 1000 – 1400.

Philippe Corcuff (video participation).

Donovan Hernández.

Jorge Alonso.

Raúl Zibechi.

Carlos Aguirre Rojas.

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Friday, May 8. CIDECI. 1700 – 2100.

Carlos González.

Hugo Blanco (video participation).

Xuno López.

Juan Carlos Mijangos.

Óscar Olivera (video participation).

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN.

Saturday, May 9. CIDECI. 1000 – 1400.

Jean Robert

Jérôme Baschet

John Berger (written message)

Fernanda Navarro

Participation by the Sixth Commission of the EZLN

Closing Ceremony

Third.- As of April 29, 2015, 1,528 people have confirmed their participation. Of them, 764 state they are adherents to the Sixth, 639 state that they are not adherents, 117 state that they are from the free, autonomous, alternative, or whatever you call it press, and 8 work for the Paid Press.

Fourth.- Those people who are not able to register prior to May 2, 2015, can do so directly at CIDECI , in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas.

That’s all for now.

Have a good trip.

From the office of the concierge,

SupGaleano

April 2015

STAND UP! Comedy: A Benefit for autonomous Zapatista education

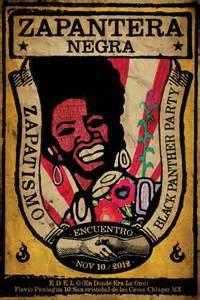

Just added: Zapantera Negra Art Exhibit…

FRIDAY, MAY 15, 2015 – 8:00 – 10:30 PM

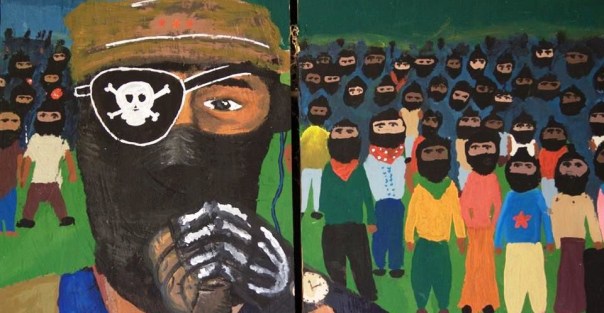

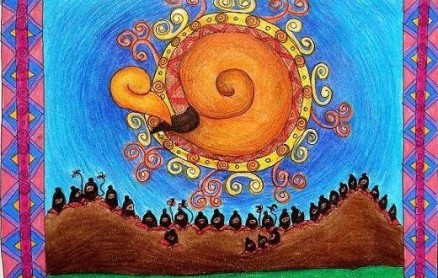

The Chiapas Support Comittee is excited that Caleb Duarte will be collaborating to exhibit the Zapantera Negra art project at this event. Caleb is an artist and curator of the Zapantera Negra project, a collaboration between Emory Douglas, former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party, and local and international Zapatista artists.

PLEASE JOIN US on FRIDAY, MAY 15, 2015 – 8:00 – 10:30 PM at:

THE OMNI COMMONS

4799 Shattuck Ave., Oakland, CA 94609

Admission: $12.00. Tickets at the Door and in advance through Brown Paper Tickets:

http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/1475108

And on Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/events/375091909366280/

We’d really like to have you join us this Friday; but if you can’t, you can still buy a ticket through Brown Paper Tickets to support autonomous Zapatista education.

http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/1475108

For more Information: Chiapas Support Committee/Tel: (510) 654-9587

Email: cezmat@igc.org

7 months after: investigative journalists talk about Ayotzinapa

7 Months After: investigative journalists talk about the Ayotzinapa Case

Seven months after the attack on Ayotzinapa students, I remembered that unspeakable crime by attending a talk at my local branch library (Temescal) in Oakland. For several hours last Saturday, Anabel Hernández and Steve Fisher talked about their work as investigative journalists. Both are postgraduate fellows at the University of California Berkeley’s School of Journalism in the Investigative Reporting Program. [1] They are currently investigating the Ayotzinapa Case and have written several articles for the Mexican weekly Proceso.

Hernández and Fisher have debunked the federal government’s official version of the Ayotzinapa Case piece by piece. For example, the federal government denied that the Federal Police were involved. Hernández and Fisher obtained a key piece of evidence that told a different story: the September 26, 2014 monitoring record from the Center for Control, Command, Communications and Computation (C4), a computer-monitoring center connected to both state and federal police. That C4 monitoring record showed that the students were monitored from the minute they left Ayotzinapa for Iguala and that their location was reported to the Federal Police.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the government’s official version concerned the alleged “motive” for such a heinous crime: José Luis Abarca, Iguala’s mayor at the time in question, supposedly ordered the attack because he was afraid that the students would disrupt his wife’s presentation of her DIF [2] activities. The official version goes on to say: following the mayor’s orders, municipal police from Iguala and from the neighboring municipality of Cocula attacked and captured the students while the United Warriors (Guerreros Unidos) criminal gang murdered and then incinerated them, without the knowledge of the federal agents and soldiers stationed in the zone.

Hernández made a big point of saying that there is no way the mayor of Iguala and his small municipal police force, even with the aid of Cocula’s municipal police and “Guerreros Unidos,” had the ability to pull off an operation like the disappearance of 43 college students and the attack that preceded it. She stressed that the mayor was a “nobody” and Guerreros Unidos were never even heard of before this tragedy. She emphasized that Iguala was a place where large federal institutions dominated: the federal police, the Army and offices of federal agencies like Governance (SG) and the Attorney General (PGR).

It has been reported in the Mexican press that no murder or kidnapping charges have been brought against Abarca because there is no evidence to support either charge. A member of Caravana43 stated the same thing in a talk at Boalt Hall, the UC Berkeley Law School, and Hernández emphasized it. She added that Abarca’s wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa, had finished her presentation and left the area by the time the student’s reached Iguala. The presentation of Abarca’s wife was not the motive for the attack!

As for the “confessions” from alleged members of Guerreros Unidos, Hernández said that photos of their appearances before a judge showed obvious signs of torture. The significance of this is that their confessions were obtained under torture and, therefore, should not be upheld up in court of law.

So what actually did happen? Who ordered and/or planned the attack and the disappearances and why? That is what Hernández and Fisher continue investigating. They want answers. So far, they have obtained information from the reconstruction of the crime, pieced together by the parents’ lawyers with survivors of the attack, as well as from cell-phone videos taken by survivors. They have obtained government documents and interviewed both survivors and detainees. They stated that they are planning to investigate why the EPR (Ejército Popular Revolucionario, EPR) issued a statement shortly after the attack pointing fingers at the Mexican Army as responsible for the murders and enforced disappearances. A baseless accusation or does the EPR know something? The parents certainly seem to believe that the Army was responsible. At the talk I attended in Berkeley a member of Caravana43 specifically said the parents and survivors believe the Army is responsible.

There was a hint in the first Proceso article by Hernández and Fisher that the leftist politics of the school may have been a motive:

“Moreover, according to the information obtained by Proceso at the Ayotzinapa Teachers College, the attack and disappearance of the students was directed specifically at the institution’s ideological structure and government, because of the 43 disappeared one was part of the Committee of Student Struggle, the maximum organ of the school’s government and 10 (others) were “political activists in formation” with the Political and Ideological Orientation Committee (Comité de Orientación Política e Ideológica, COPI).” [3]

And there was also an implication in the Saturday talk that the government suspected a connection between the students and the EPR or the ERPI [4] and that could have been the government’s motive.

The question and answer session was interesting. One of the questions that is always asked at public discussions involving the Drug War in Mexico is whether legalizing drugs here in the United States would solve the problem of violence in Mexico. What seemed to be of greater concern than legalizing drugs, at least from the journalists’ perspective, was ending the military aid that trains soldiers and police how to kill more effectively and provides them with the weapons needed to do so. Hernández believes those weapons and training are not used against drug traffickers or organized crime, but rather against the (innocent) civilian population.

Why has the Ayotzinapa case won so much support in Mexico and the world? Anabel Hernández answered that question by saying that since the beginning of Mexico’s Drug War, the federal government has generally blamed the victims; in other words, when government security forces (Army, Navy or federal police) cause civilian deaths, the federal government alleges that those civilians were working for drug trafficking gangs or had a family member involved in drug trafficking. She went on to say that the government likewise tried accusing the Ayotzinapa students, but it was so ridiculous that it wasn’t believed. Because the government could not connect these students to organized crime, the students represent the hundreds of thousands of innocent victims of the government’s Drug War and all those citizens that live in fear of the next massacre or disappearance. Thus, the parents of the dead and disappeared students and the survivors of the attack speak with an unprecedented moral authority.

The passion with which Anabel Hernández spoke was contagious and many of those asking questions were also passionate. A final thought I came away with was that Mexico’s Drug War affects everyone, regardless of skin color, economic status or social class.

I also came away with a question I have had for several years and one that was asked by another member of Saturday’s audience: Why isn’t there more of an effort in the U.S. to end the Merida Initiative and stop the supply of weapons to Mexico?

Submitted by Mary Ann Tenuto-Sánchez

——————————————–

[1] For more information about Hernández and Fisher and the program see: http://journalism.berkeley.edu/news/2014/dec/19/irp-fellows-investigate-governments-role-disappear/

[2] DIF – These are initials for the National System for Integral Family Development, a welfare program for families administered through the President, Governor and Mayor’s offices. The wives of the president, governor or mayor are usually the ones responsible for carrying out these responsibilities.

[3] http://www.proceso.com.mx/?p=390560

[4] Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo Insurgente, an armed group in Guerrero

SupGaleano: Report on registration for the seminar

REPORT ON REGISTRATION FOR THE SEMINAR “CRITICAL THOUGHT VERSUS THE CAPITALIST HYDRA”

Zapatista National Liberation Army

Zapatista National Liberation Army

Mexico

April 21, 2015

To the Compas of the Sixth:

To the presumed attendees of the Seminar “Critical Thought Versus the Capitalist Hydra”:

We want to let you know that:

As of April 21, 2015, the number of people who have registered for the seminar “Critical Thought Versus the Capitalist Hydra” is approximately 1,074 men, women, others, i children, and elderly from Mexico and the world. Of this number:

558 people are adherents of the Sixth.

430 people are not adherents of the Sixth

82 people say they are from the free, autonomous, independent, alternative, or whatever-you-call-it media.

4 people are from the paid media (only one person from the paid media has been rejected, it was one of the three who were sponsored by the Chiapas state government to sully the name of the Zapatista Compa Professor Galeano and present his murderers as victims.)

Now then, we don’t know if among those 1,074 who have registered so far there might be a portion who have gotten confused and think that they have registered for Señorita Anahí’s wedding ii (apparently she’s marrying somebody from Chiapas, I’m not sure, but pay me no mind because here the world of politics and entertainment are easily confused… ah! There too? Didn’t I tell you?)

Anyway, I’m sharing the number of attendees because it’s many more than we had expected would attend the seminar/seedbed. Of course now that’s CIDECI’s problem, so… good luck!

What? Can people still register? I think so. I’m not sure. When questioned by Los Tercios Compas, Doctor Raymundo responded: “no problem at all, in any case the number of people who will actually pay attention are far fewer.” Okay, okay, okay, he didn’t say that, but given the context he could have. What’s more, not even the Doc knows how many people are going to come to CIDECI.

In any case, if you are engrossed by the high quality of the electoral campaigns and are reflecting profoundly on the crystal clear proposals of the various candidates, you should not waste your time on this critical thinking stuff.

Okay then, don’t forget your toothbrush, soap, and something to comb your hair.

From the concierge of the seminar/seedbed, In search of the cat-dog,

SupGaleano. Mexico, April 2015.

The Cat-Dog in the chat “Zapatista attention to the anti-Zapatista client”: (You are currently on hold, one of our advisors will be with you in a moment. If it takes awhile, it’s because we’re on pozol break. iii We thank you for your patience.)

“

Hello? Can you hear me?”

“Ah yes hello, I would like to register.”

“Listen, are there still seats available?

“Ah okay, but listen, the thing is that I want a seat really close to the front, you understand?

“Hey listen, will there be a chance for a selfie, and autographs, and all that?

“Yes, listen, another question, in the registration process are you giving out some kind bonus, as they say?”

“What! This isn’t the registration for the Juan Gabriel concert?

“Damn! I knew it. I told the gang that if we didn’t hurry up we weren’t going to get a seat.”

“Alright listen, if there aren’t any seats left for Juan Gabriel, then give me one for Jaime Maussan.”

“What, no seats for Maussan either! Alright then, tell me where there are seats.”

“Oh really? So you guys are trying to be really postmodern huh? Very metaFukuyama and all that, right?

“Listen, let me recommend for the subject of postmodernism, José Alfredo Jiménez and his classic aphorism of “life isn’t worth a thing.” That is the real thing, not that nonsense of a nihilism of multi-colored condoms and feminine pads.

Well listen, let me tell you that what is really important is a cultured pragmatism. I mean, appropriately and pleasantly presented. For example, the Araña weaving inconfessable alliances, Meñique [Littlefinger] investing in various “scenarios,” the institutional left doubting whether it should be left or institutional, the Laura Bozzo of the vanguard of the proletariat pontificating, a lot of svelte nudes to remind you of cellulitis and stretch marks, Kirkman proposing fascism as the best option in times of crisis, Rick and Carol exactly like they are, Tyron exchanging Cercei for Khaleesi, the “investigative journalism” searching out who will do their work for them with the slogan “go ahead and denounce, we’ll see if we can get paid for printing it.” Yes, what Alejandría needs are less Latinos and African Americans, and more figures along the line of Justin Bieber and Miley Cyrus. There, you see, even the fucking dragons changed political parties and the Starks are having trouble getting their party registered. And later Mance Rayder wanted to be all freedom loving and all, and they killed him for not wanting to vote. Ah, but in the game of thrones that matters, what’s really worth something is on the island of Braavos. Seven Reigns be damned! Winter is coming and “The Iron Bank will get what belongs to it.”

“Anyway, I’d give more spoilers, but better not to. I’ll leave you in doubt, suffering…”

Hey listen, are you sure there aren’t any seats left? Not for Neil Diamond either? Sonora Santanera? Not even Arjona?

Hey listen I’m confused. Isn’t this where you register for shows and performances? You know, like the movies, theater, concerts, comic routines, electoral campaigns, Don Francisco, circuses with animals on the ticket [ballot], candidacies, reality shows, green advertising spots on Imax screens, “Stop suffering” propaganda charged to the public treasury, lose weight by jogging to the ballot box?

“I knew it!” Fucking Peñabots! They have to be promoting abstention. Don’t they understand they’re just playing to the right? Don’t they see the great advances of the progressive governments in the world? I’m sure that you are a renter or have a mortgage to pay, right. And here I am, with my own house, trying to orient and guide you, and you all over there stuck in sadomasochism. I hope you get sick from that sandwich with salmonella! There you have your unlaic [unlike], your mute, your block, and your unfolou [unfollow]! So let’s see how you survive now eh!

(The user has gone offline. The chat session is over. End of transmission). (…) (sound of liquid being poured). (…) (voice stage left): Who spilled pozol agrio on the keyboard?! I told you not to let the cat-dog use the computer! Oh just wait until I find him, then he’ll see!

I testify.

SupGaleano

Woof! Meow! (And vice versa).

Translator’s Notes:

[i] The text uses “otroas,” to give a range of possible gendered pronouns including male, female, transgender and others.

[ii] Anahi is the singer/actress engaged to the Governor of Chiapas. Their elaborate (expensive) wedding will soon take place in Chiapas, one of the country’s poorest states.

[iii] pozol agrio is a drink made from corn