By Andrea Cegna | Desinformémonos | January 2, 2026

“The word ‘common’ is not just anything,” declares Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés from the stage in Oventic, Caracol II, during his speech commemorating the thirty-second anniversary of the start of the Zapatista revolution. The EZLN leader adds: “It is much more difficult and much greater than that of ’94. Because it means uprooting the capitalist system. It means removing from our minds what they have forced upon us.” And he immediately clarifies the scope of this break: “We don’t want to be owners. I’m not just talking about the land, but about everything. We no longer want ‘mine’ or ‘I.’ What we mean by ‘the common,’ perhaps some will say it’s madness. Yes, we can accept that: madness. But for everyone, not just for a few.”

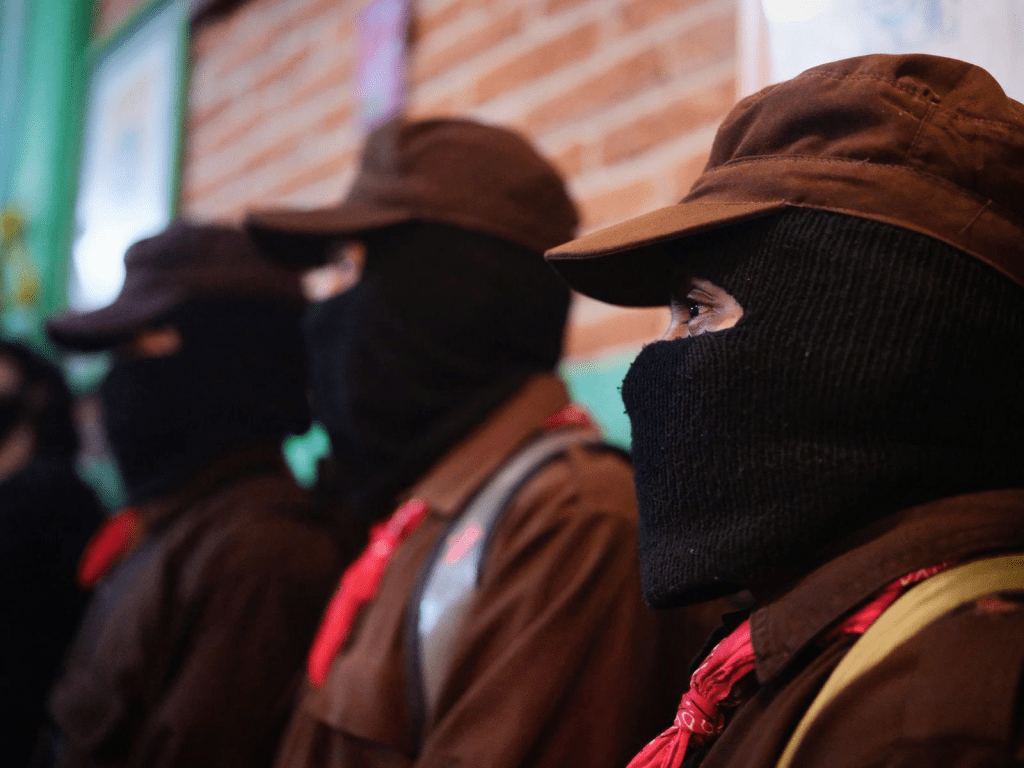

In the mist that since morning has enveloped one of the best-known headquarters—also due to its proximity to San Cristóbal de Las Casas—of neo-Zapatismo, the central event of the celebrations opens a spatial-temporal crack. When the EZLN General Command takes the stage, the mist lifts, the music stops, and in the distance, the sound of the militia’s staffs can be heard, which, as part of the opening, burst forth in front of the stage, marking the rhythm of the night.

The EZLN is an army that wants to build peace, is tired of war, wants life and not death, and precisely for this reason it is anti-capitalist: capitalism as a systemic element of the destruction of life, in all its forms, in the name of the obsession of accumulating wealth. Moisés says it without mincing words: “That is why we say and confirm that we will continue in our political, ideological, and peaceful struggle. Because we do not want death. We want life. But we want a life that we decide for ourselves, not one decided by those above us.”

And he adds: “We will always be peaceful. And if they don’t allow us to be, we will defend ourselves as our fallen comrades taught us thirty-two years ago. We are like them. And like them, we are ready and willing.” “We have a great responsibility, comrades. And we are going to do it because there is no other option.”

An intense, emotional, and lengthy speech, which shows the growth of Moisés, called upon about a decade ago to take the place of one of the most iconic revolutionary figures of the modern world: Marcos. A courageous decision by the EZLN, which revealed a distinct and complex nature, deeply rooted in the worldview of the indigenous peoples, but not solely in that.

Constructing a new relationship with life

Marcos has not disappeared and has reappeared these days at CIDECI in San Cristóbal, intervening on several occasions in the “seedbed,” which in Italian could be translated as a word related to the world of agriculture and not to debates and seminars, and which in the Zapatista conception is a space for training that sows seeds to harvest anti-capitalism. Marcos spoke again in the form of a narrative, a choice made years ago to be able to communicate with the indigenous communities and make the analyses of the revolutionary vanguard—which on November 17, 1983, gave life to the first camp—understandable and replicable.

In addition to the narrative read on December 29, Marcos added twelve points. “The crucial question is: is it possible to construct a geography and a calendar, a spatial-temporal eruption, in which another logic of production and relationship with nature allows—mind you: allows, not necessarily creates—a new form of relationships between living beings, considering nature as the whole of which humanity is only a part?” he says in the seventh point.

In the last point, he returns to the war: “The ‘failures’ and ‘dysfunctions’ of the system are not failures or dysfunctions: they are an essential part of a war machine that advances by conquering through destruction and annihilation, only to then rebuild and reorder social relations. Social programs like Sembrando Vida and its “welfare” equivalents do not fail or are incomplete: they fulfill their function and role in the war of conquest. With historical myths, recommendations, and advice to young people, the elders urge them to face the storm with a toothpick and demand that they be grateful for life. It’s actually a small stick, but I think you understand it as a toothpick. In the Zapatista communities, facing the present and thinking about the future, they return to their own history.”

The EZLN, today, proclaims and practices a political space where property and the pyramid are set aside, not to be replaced by new elites

But looking at the EZLN solely through the lens of its political and theoretical leadership is a mistake that has been repeated time and again. Because what Zapatismo truly calls into question is not only capitalism as an economic system, but the pyramid of power that makes it possible: the idea that someone must be at the top and someone at the bottom, that command is concentrated and life is reduced to obedience. The pyramid is the symbol of this world order, just as private property is its material foundation.

The Oventic fog lifts around 11 p.m., just as the EZLN Command takes the stage and neo-Zapatista militia members occupy the center of the basketball court at Caracol II. Earlier, for hours, theatrical performances and marimba music filled the afternoon; the communal dining hall provided food; in another corner of the Caracol, beef broth was distributed free of charge. This is not mere decoration: it is concrete politics. Collective organization, care, daily life that functions without a market and without vertical command.

Building autonomy from below

The Common, as Moisés affirms, is the radical questioning of both foundations of capitalism: property and the pyramid. Questioning property means breaking with the idea that land, labor, time, and life can be appropriated. Questioning the pyramid means rejecting the accumulation of power and its separation from the communities. The EZLN, today, proclaims and practices a political space where property and the pyramid are set aside, not to be replaced by new elites.

It’s not about rhetoric, but about daily organization. The strength of the EZLN lies in its ability to build autonomy from below: in community assemblies, in the Caracoles as spaces of coordination and not command, in the rotation of responsibilities, in the collective control of decisions. It is there that the pyramid is emptied, because it finds no place to take root. It is there that politics ceases to be representation and becomes shared practice once again.

Zapatismo is no longer fashionable today. It is outside the mainstream media, outside the constant narrative, and there are those who lose their bearings or file it away as a myth of the 1990s. But precisely away from the spotlight, it continues to resist: forced migration, the advance of organized crime, militarization, the reassuring narrative of the central government and the media that speak of development and pacification while dispossession and violence advance in the territory. The EZLN survives not because it has become an icon, but because it is a living political process, capable of reorganizing itself and resisting the passage of time without abandoning its principles. In this sense, Zapatismo is neither a nostalgic memory nor a closed chapter: it is a revolution that does not seek to seize power, but to dismantle it. And precisely for this reason, it remains unsettling. And necessary.

_________________________________________________

Read the original in Spanish here at Desinformémonos. Snap translation by Chiapas Support Committee.