Chiapas Support Committee

Home of the Compañero Manuel blog on zapatistas & mexico

Nuns Assaulted in attack on 10 de Abril Zapatista community

Nuns Assaulted in attack on 10 de Abril ejido, and are impeded from attending to the injured

** They retain an ambulance, a pickup truck, the driver and a doctor, in Chiapas community

** Attempts to take possession of Zapatista lands, which began in 2007, continue

By: Hermann Bellinghausen, Envoy

San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, February 2, 2014

During the attack of residents from November 20 ejido (Las Margaritas) on the 10 de Abril (April 10th) ejido (autonomous zapatista municipality of 17 de Noviembre), last January 30, denounced yesterday by the Good Government Junta of the Morelia Caracol, not only were three EZLN support bases gravely injured, but personnel from the San Carlos Hospital in Altamirano were also attacked and impeded from attending to the injured.

Sister Patricia Moysén Márquez, known for many years in the Altamirano region for her work at the San Carlos Hospital and her closeness to the indigenous communities, relates what happened: “At approximately 7:30 AM we received a call to go to help the injured because of a problem in 10 de Abril (April 10th) community. The ambulance left with the driver, a doctor and a sister.” A pickup truck followed it, “because of not knowing the number possibly traumatized.” At the San Miguel intersection “we encountered lots of people from November 20 (community) with sticks and machetes.” Another group intercepted them farther ahead.

“Sister Martha Rangel Martínez and I were riding behind the ambulance. We identified ourselves and said that we were going because of a call for aid due to the fact that there were people injured. Their reaction then was that ‘they were going to burn the pick up because we are from the government and the problem will be solved faster like that’. We told them that we are not from the government but rather the Church. They said that then we were Zapatistas that we are going to support our group. We said that we were going to see those injured of whatever religion or party; the problem that they had was not our issue, only the injured.”

They pulled out the ambulance driver “and some said that we could pass then, but we had to take out the injured from both parties, if it was not like that then the driver was going to be taken to November 20. I told them that it was better that the ambulance enters and better that we stay. But another group arrived that said that no one is going to pass, that the government has to resolve it and that the ambulance as well as the pickup truck are going to be burned right there.”

Sister Patricia continues: “As I did not want to give them the key or get out, they said that they were going to turn the pickup truck over. We insisted a lot to them on the urgency of saving the life of anyone that was injured.” After a while the ambulance returned. “Someone from November 20 was driving. They began to hit our pickup with sticks, trying to open the doors. I don’t know how they opened the passenger door and pulled Sister Martha out. I had to make the turn, as they wanted, Sister Martha got in with many more of them, they told me that I should go to the intersection and we got out, but I didn’t want to give them the keys, I put them in the pocket of my habit, because I saw that they pulled the ambulance towards November 20.”

Then, the religious woman continues her story, the women from the same group “they started to molest us, trying to take the keys away from me. As I resisted, they began to undress us. They put their hands wherever they wanted and held both of our arms. They hurt us, tore my jacket and took out the keys and my coin purse where I have all my documents. I asked them to return it to me but they roundly refused.”

A little later the Cioac members “took off with the pickup and all their cars, which were many, full of people, the majority men from November 20. Sister Martha and I got a ride back to Altamirano to give warning.” When the acts were reported at the hospital, two people arrived that: “identified themselves as politicians from the state government working in Altamirano, Juan Baldemar Navarro Guillén, assistant delegate, and Jorge Alfredo Jiménez, political operative.” Towards 11:40 AM, the driver, the doctor and the first religious woman achieved returning, but the ambulance and pickup truck remained in November 20. The municipal president of Altamirano promised to recover them.

There were warnings from the Junta

The foolhardy attempt to take possession of Zapatistas lands by the robbers from the Cioac began to get out of control on November 13 but according to what the Junta of the Whirlwind of Our Words Caracol said this Saturday, the first time that “they provoked us to take away the land we recuperated in 1994 was in 2007,” because “they wanted to become the owner.” On October 18, 2013, residents of November 20 attempted it again.

The most recent provocation to the Zapatista bases of April 10 had occurred last Monday, January 27, when 250 people from the Cioac democratic destroyed the signs at the ejido’s entrance and proceeded to cut down the trees “that we have as an ecological reserve,” according to the Junta, with five chainsaws: nine pines, 40 oaks, 35 coffee bushes and three banana trees. Removed levels, boards, firewood, “not for family use, were stolen to sell them, taking them away in a total of 41 pickup trucks.”

—————————————————-

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Monday, February 3, 2014

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/02/03/politica/011n1pol

Murder in the Lacandón Jungle; background on Viejo Velasco Massacre

Murder and Other High Crimes in the Lacandón Jungle

By: Mary Ann Tenuto-Sánchez

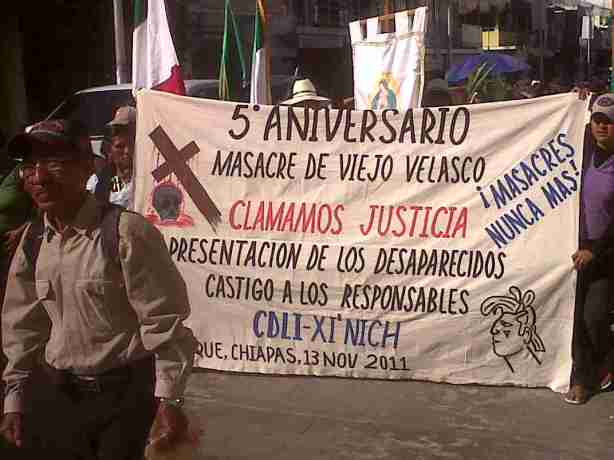

On November 13, 2006, an armed attack occurred against the indigenous community of Viejo Velasco Suárez, in the Lacandón Jungle of Chiapas. Four people died as a result and another four people are disappeared and presumed dead. Two people were detained by police, one of them a health promoter from a neighboring community who had gone to help, the other, one of the attackers. Information about the political organization of those attacked was confusing. The state government claimed those attacked were affiliated with Xi’ Nich, an independent Chol organization usually friendly (sympathetic) to the EZLN. Xi Nich claimed those attacked were affiliated with the EZLN. The EZLN finally released a statement clarifying that those attacked were not Zapatistas. That clarification did not, of course, reveal the political affiliation of the victims.

The attackers were members of the Lacandón Community from Nueva Palestina, recipients of a communal land grant to a group of Indigenous people whose origins are in dispute, but today are known as Lacandón Maya. After much protest, some Chol and Tzeltal Maya were also included in this communal land grant. The history is that during the 1950s and 1960s, the Mexican government encouraged land-hungry campesinos from other parts of Chiapas to migrate to the Jungle with a promise of land. This was done to get those campesinos and their militant organizations off the backs of the mestizo landowners.

After enticing them into the Jungle, the government turned around and in 1972 gave the land to a different group of indigenous people known now as the Lacandóns, placing the land of all the others who lived there in jeopardy. We are talking about more than one million acres of land given to just 66 Lacandón families (several hundred people), who had not even asked for it! The government’s treachery caused such an uproar that it soon had to offer some of the other Mayan language groups, specifically Chol and Tzeltal peoples, a chance to relocate within what the government called the Lacandón Community and to own a little piece of the communal wealth. This offer was on the condition that they would live in specified settlements. Some accepted. Other settlers belonged to campesino (peasant) organizations that resisted resettlement and struggled for years to legalize those communities that had already existed prior to the creation of the Lacandón Community.

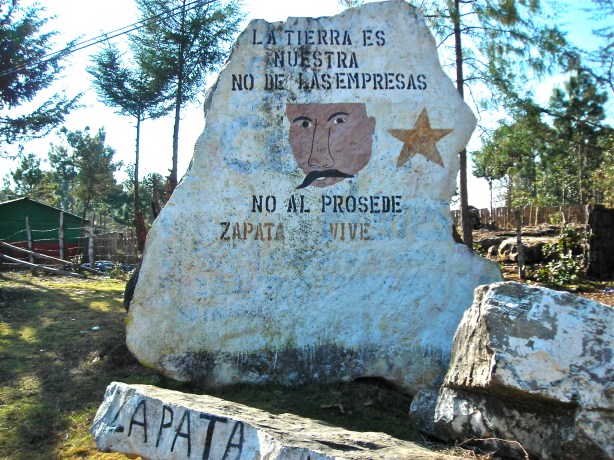

It was partly from those communities that resisted resettlement and their campesino organization that the EZLN was born. Not only were those existing communities endangered; all the settler communities, whether inside or on the outskirts of the Lacandón Community were threatened. Their ability to expand as their population grew was cut off forever by that government decision. What was the government’s motive for such an apparently stupid decision? The answer is greed; greed for the precious wood in the rain forest! The Lacandóns and those Chol and Tzeltal people who accepted living in settlements also agreed to give the government the legal right to cut down mahogany and cedar trees within the Lacandón Community (for a price, of course). Speculation is that one of the motives for the violent attack on Viejo Velasco is that the community’s land contains a large grove of mahogany forest. The attackers from the Lacandón Community claim that they are the legal owners of the land on which Viejo Velasco is located and that they want to evict the “invaders.” This, in spite of the fact that negotiations with Mexico’s Agrarian Reform agency were close to legalizing Viejo Velasco. Plainly, someone did not want that community legalized!

Among the group of attackers were armed men wearing several types of uniforms. Some wore state police uniforms and carried high-powered weapons. In other words, they carried very expensive weapons only legal for use by police and military. Where did indigenous peasants get the money to buy such weapons? At least one human rights group identified them as members of the Opddic, a group of PRI members, allegedly organized and funded by local cattle ranchers and the municipio of Ocosingo, belonging to the PRI. Opddic is the acronym for the Organización para la defensa de derechos indigenas y campesinos (Organization for the Defense of Indigenous and Campesino Rights, in English).

In spite of the fact that the EZLN had clarified that it was not involved, articles soon began to appear in the Mexican press about some Lacandóns fleeing to a museum in San Cristóbal de las Casas, saying that they feared reprisals from the EZLN!

The plot thickened a week after the Viejo Velasco murders when the Opddic announced that it would no longer recognize the authority of the Zapatista Good Government Juntas and that it intended to take back vast quantities of land in four official Chiapas counties (municipios), land now belonging to the Zapatista Caracols of Morelia and La Garrucha. This is an ominous sign for both independent organizations and for the Zapatista communities. It is very close to being a declaration of war over land and territory! In the Lacandón Jungle, it’s all about land; who uses it and who controls it. Mother Earth is the essence of life itself and, like their namesake Emiliano Zapata, the Zapatistas believe that the land belongs to those who work it. The entire incident in Viejo Velasco and its aftermath reek of a counterinsurgency move.

Several Zapatista Juntas responded to the Opddic threat by saying that they were prepared to defend the land they “recuperated” on January 1, 1994. Then, another player upped the ante even further. Approximately one month after the Opddic statement, shortly before the Encuentro Between the Zapatista Peoples and the Peoples of the World, an organization calling itself the “Fundación Lacandona, A.C.” (Lacandón Foundation) introduced itself by sending a document to the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center. The document is entitled “The Face of the Lacandón Community” and written by the Fundación Lacandona and the Opddic. For openers, the document admits that the signers are responsible for the murders in Viejo Velasco! However, it points to several human rights organizations and the director of Maderas del Pueblo del Sureste and an ecologist, Miguel Angel Garcia, as being murderers of their members. The human rights organizations targeted by the “Fundación Lacandona” are among those that investigated the Viejo Velasco killings, including Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center. That human rights center has petitioned the Inter-American Human Rights Commission to ask the Mexican government to take precautionary measures to protect those involved; especially, Miguel Angel Garcia and his family.

According to an article in La Jornada, Opddic grew tremendously during the six-year presidential term of Vicente Fox and the governorship of Pablo Salazar (2000-2006), “occupying territorially spaces before covered by the paramilitary groups MIRA (Canyons Region), Chinchulines (Chilon), and Paz y Justicia (Tila, Sabanilla, Salto de Agua and Palenque).”

The Opddic, which exhibits some characteristics of a paramilitary group, now seems to have all kinds of money with which to entice others into joining. In the Zapatista autonomous municipios within the two Caracols specified in the Opddic’s document, there are indigenous people who belong to different political organizations living together in the same canyons. There are members of independent organizations, often friendly to the Zapatista communities. There are also PRI members who cooperate with the Zapatistas, as well as hostile PRI members who do not always cooperate. There are people of different religions. Now, some of the independents and many of the friendly PRI members are joining the Opddic! The hostile PRI members have been part of Opddic for as much as four or five years.

This new alliance of forces is worrisome. The Opddic has been causing problems since at least August 2002 when some 200 of its members led an armed attack on Nuevo Guadalupe Quexil. Since then, it has been starting disputes over land with Zapatista communities, threatening to kill Zapatista authorities, entering Zapatista communities and damaging houses. So far, the Zapatistas have been able to resist without resorting to violence. As for the Lacandón Community, its relations with other organizations living in the Jungle have not been friendly since the Mexican government and international conservation NGOs allegedly encouraged its members to assert their property “rights” over the more than one million acres of land granted to them by the federal government.

On February 8, Subcomandante Marcos, on behalf of the General Command of the EZLN, made public a strongly-worded communique responding to the Opddic’s threats, alleging that Opddic is a criminal organization which engages in the illegal cutting and trafficking of precious woods, as well as in drug trafficking and stolen vehicles. The Zapatistas also stated plainly and forcefully that they are prepared to defend all their land against the Opddic.

There is great concern in Chiapas about the imminence of further attacks like the one on Viejo Velasco. The unholy alliance between the Opddic and the “Fundación Lacandona” has specifically threatened the communities of Flor de Cacao, Nuevo Tila, San Jacinto, Ojo de Agua Tzotzil with violent eviction if those communities are not abandoned. The communities threatened are composed of indigenous people belonging to independent organizations and some Zapatista support bases.

These are not interethnic squabbles as some, including the Mexican government, might lead you to believe. This is a continuation of the struggle for land and natural resources that has gone on ever since the Spanish Invaders took the land away from its indigenous owners. Those pulling the strings and doling out the money to the Opddic have economic interests in the jungle’s natural resources; such as, precious woods (mainly mahogany and cedar), water (for generating electricity and bottling), oil and other minerals, ecotourism and biodiversity.

Mary Ann Tenuto-Sánchez

Chiapas Support Committee

February 2007

Viejo Velasco Massacre, 7 Years Later

Impunity Prevails 7 Years After the Viejo Velasco Suárez Massacre

By: Hermann Bellinghausen

Palenque, Chiapas, January 30, 2014

Seven years after the ignored massacre of defenseless and peaceful Indigenous in Viejo Velasco Suárez community, in the Lacandón Jungle in the northern part of Ocosingo municipality, there is only government disdain, and not only impunity for the material and intellectual authors of the act, but also criminalization of neighbors from the Nuevo Tila ejido that aided the victims, their compañeros. That, while it is known through numerous direct testimonies that the crime was perpetrated by Tzeltal residents of the so-called Lacandón Community coming from Nueva Palestina and state police, in the presence of the Lacandón authorities of Lacanjá Chansayab.

In a Kafkaesque logic, the state’s Attorney General (PGJE) blamed the innocent ones that helped out. Thus, they tortured and held Diego Arcos Meneses, from Nuevo Tila, prisoner for a year, and arrest warrants currently exist against more residents of the same ejido. The Chols Antonio Álvarez López and Juan Peñate Díaz are filing for a injunction (amparo) to protect them from arrest. Another two are about to do it. Their innocence is obvious in the four cases, and above all their “guilt” was being in solidarity with the Viejo Velasco Suárez victims, a town now abandoned and destroyed in the Lacandón Jungle.

On November 13, 2006, during the government of Pablo Salazar Mendiguchía, around 40 individuals dressed in civilian clothing, coming from Nueva Palestina, accompanied by some 300 agents from the then Sectorial Police attacked with firearms the Tzeltal, Tzotzil and Chol families that used to live in Viejo Velasco. The attack left seven dead from these families, two disappeared (very probably dead, which would be nine murdered), the displacement of 20 men, eight women, five boys and three girls. Petrona Núñez González, a survivor of the massacre, died in 2010, as a consequence of post-traumatic stress.

Seven years after the acts, a dozen social organizations and human rights centers pointed out that the violation of guaranties continues, “since the 36 people that fled on the day of the massacre continue displaced from their community of origin in different Chiapas municipalities, in a vulnerable state and in continuous violation of their rights indicated in the United Nations’ Rector Principles for the Internally Displaced.”

Demanding that the State do “everything necessary to find out the truth about what happened and so that those responsible are sanctioned,” reiterated that Mariano Pérez Guzmán and Juan Antonio Peñate López continue disappeared “and the police investigations have been stopped, before a lack de interest from the PGJE to find their whereabouts.” Meanwhile, the state authorities continue without investigating or arresting those responsible for “this action of a paramilitary cut.” According to investigations of the state attorney general, Frayba, Desmi, Serapaz, Xi’Nich, Sadec and others add (13/11/13), the responsibility corresponds to members of the Organización For the Defense of Indigenous and Campesino Rights (OPDDIC) of Nueva Palestina and to members of the state’s Sectorial Police.

On the other hand, the PGJE continues legal harassment against residents of Nuevo Tila, a neighbor community to Viejo Velasco. “They were the first to offer help to the injured, to receive the displaced people and support in the search for the disappeared.” Those ejido owners even received the K’anan Lum “jTatic Samuel Ruiz García” human rights award in 2011. Nevertheless, they are the ones who have arrest warrants. The compañeros of those killed are pursued, not those who it is known carried out the massacre. Their motive is known, and that of their Lacandón accomplices. And the sectorial police did not act on their own account; they were obeying orders.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

Friday, January 31, 2014

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/01/31/politica/021n1pol

Zapatista News Summary – January 2014

JANUARY 2014 ZAPATISTA NEWS SUMMARY

In Chiapas

1. Zapatistas Celebrate 20 Years of Resistance! – On January 1, 2014, the Zapatistas celebrated the 20th anniversary of their Rebellion and Resistance. They hosted approximately 5,000 students between the 2 Escuelitas, one during the week before January 1st and one the week afterwards. Students from both sessions also attended the anniversary celebration, along with many other supporters who joined in. The Huffington Post published an article by a journalist that attended the Escuelitas and then the New Year’s celebration in Oventik. We are awaiting communication from the EZLN about the dates for the next Escuelita.

2. Chiapas Ejido Files Suit Against San Cristóbal-Palenque Toll Road – On January 6, Los Llanos, a Tzotzil community in the rural part of San Cristóbal Municipality, filed suit to stop construction of the San Cristóbal-Palenque Toll Road. On January 13, the court issued a temporary injunction until there is a decision on the case. We posted a translation of the news article on our blog. The toll road is one of the infrastructure projects envisioned within the Plan Puebla Panamá (now renamed the Mesoamerica Project) to facilitate tourism. Los Llanos is across the road from the Mitziton ejido, which has a history of conflict and protest over the toll road’s construction.

3. San Sebastián Bachajón (SSB) Denounces That an Ex Prisoner Is Not Free and the Latest Move to Take Their Land – Antonio Estrada, a resident of San Sebastián Bachajón, was released from a Chiapas state prison on Christmas Eve. However, he has to report to and sign in at a court in the state capital every week. Apparently there is still an unresolved federal case against him for carrying a weapon intended for the exclusive use of the Mexican Army. On January 24, a court granted Estrada a protective order against that charge, which opens the door for absolving him of that crime.

The ejido owners also accuse a pro-government faction in the SSB ejido of attempting to fabricate yet another false assembly act in order to dispossess them of the portion of land in dispute since 2011.

4. Those Displaced from the Puebla Ejido Return to Harvest Coffee – From January 17-27, those displaced from the Puebla ejido nearly 5 months ago returned to harvest their coffee fields. Members of social organizations accompanied them. Although they received insults and threats, they were able to harvest their fields and then return to the refugee camp in Acteal. Many of the 98 displaced individuals are members of Las Abejas of Acteal, an adherent to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration.

5. Tila Ejido Obtains Court Order To Stop Land Grab – The Tila ejido is located in the state’s Northern Zone and is an adherent to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle. A portion of their ejido land lies within the town of Tila, the capital of Tila municipality. A building known as the “Casino del Pueblo” (the People’s Clubhouse) was taken over by municipal authorities some time ago and is still the subject of litigation that has dragged on for years and is pending before Mexico’s Supreme Court. Now, however, municipal authorities want to tear it down to build a commercial center and, although the building does not belong to them, are promoting a referendum on the project as a substitute for the “prior, full and informed consent” required when indigenous lands are affected by the government. On January 24, the Tila ejido obtained a court order suspending any work or construction on the ejido’s property until the case is resolved in court.

6. Dispossession in the Lacandón Jungle of Chiapas – A journalist from La Jornada toured parts of the Lacandón Jungle and filed reports on government attempts to affect the land in the northern part of the Jungle, some within the Jungle’s so-called Buffer Zone. The communities in that region are unhappy with the application of government programs like Fanar (the Fund for Support to Agrarian Nuclei without Registration, and previously called Procede), which limits the use of their land and would permit the privatization of individual plots. Fanar is being promoted by Sedatu (Secretariat of Agrarian Territorial and Urban Development) and also the Agrarian Prosecutor.

In other parts of Mexico

1. Mexican Government Temporarily Legalizes Michoacán Self-Defense Groups – On January 27, Michoacán’s Self Defense groups and the federal government signed an agreement in the municipality of Tepalcatepec, Michoacán. The agreement requires members of self-defense forces to register by name with the government, register their weapons and become enrolled in Mexico’s Rural Defense Corps under the control of the National Defense Ministry, known as Sedena. The agreement came about after a month of armed clashes between the self-defense forces and alleged cartel members, as Mexico’s federal armed forces were deployed to Michoacán. At the start of the month, Reuters published a story about the drug cartels shipping iron ore to China out of the Lazaro Cardenas Port. With respect to the Self-Defense groups, the question of who financed them was frequently raised. In the wake of signing the agreement, stories are emerging that they were financed by transnational mining companies. There is also some testimony that a rival drug cartel, Jalisco Nueva Generación, gave some of them weapons.

AND

A New Raúl Zibechi Article – We posted a new article of opinion by Raúl Zibechi translated into English on our blog. As always, there is a link to the original Spanish for those who prefer to read in Spanish.

_________________________________________

Compiled monthly by the Chiapas Support Committee.The primary sources for our information are: La Jornada, Enlace Zapatista and the Fray Bartolome de las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba).

We encourage folks to distribute this information widely, but please include our name and contact information in the distribution. Gracias/Thanks.

Click on the Donate button at www.chiapas-support.org to support indigenous autonomy.

_______________________________________________________

Chiapas Support Committee/Comité de Apoyo a Chiapas

P.O. Box 3421, Oakland, CA 94609

Tel: (510) 654-9587

Email: cezmat@igc.org

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Chiapas-Support-Committee-Oakland/

Mexico’s Armed Self-Defense Forces Surge

MEXICO’S ARMED SELF-DEFENSE FORCES SURGE

Questions, contradictory narratives and, above all, calls for calm energize the daily coverage and debate over the armed self-defense phenomenon sweeping parts of Mexico.

For their part, corporate media outlets like Televisa play up the deployment of federal police and soldiers to the Tierra Caliente of Michoacan, one of the epi-centers of the movement, graphically displaying the march of the federales in stark digital maps, while stressing proclamations from President Enrique Pena Nieto and his top officials that the federal government has taken charge of the violence-ridden region.

“The Mexican state is the only one responsible and the only one with attributions for really establishing security conditions in Michoacan,” President Pena Nieto affirmed while speaking at the recent world economic forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Nonetheless, the civilian self-defense groups continue expanding in not only Michoacan but to other parts of the country as well.

In fact, one such movement is on the verge of carrying out an unprecedented thrust into a major city.

Essentially, the discourse on the self-defense movements and their confrontations with different organized crime groups exists on two levels: an elite national and international opinion arena in which legality, institutional legitimacy and governability take precedence and a popular one in which survival, resistance and corruption fatigue predominate.

Even as the Mexican government and Michoacán’s Tierra Caliente self-defense groups signed an 8-point accord January 27 to institutionalize the ostensibly illegal organizations and draw them safely into state orbit, talk persisted in the self-defense circles of continuing forward with the encirclement and occupation of Apatzingán, the Michoacan city considered the bastion of the Knights Templar syndicate.

In the days immediately preceding the agreement, self-defense groups seized the town of Peribán and advanced out of the Tierra Caliente proper to several towns around the highland city of Uruapan.

With the latest gains, the Tierra Caliente self-defense movement has upwards of 10,000 armed members deployed in more than 30 municipalities.

At the same time, another self-defense movement based in indigenous communities and which predates the Tierra Caliente movement by almost two years is consolidating its presence in Michoacán’s Purepecha Meseta region.

In the municipality of Cherán, for instance, local residents have dismantled the former local government, driven political parties from the community and reintroduced a government rooted in Purepecha customs and traditions.

“Our system of governance is a collective one based in on a circular, non-hierarchical system,” community leader Tata Meche was quoted as saying late last year. “We got rid of the complexities of the same political system in Mexico that is used to create tricks.”

In the neighboring state of Guerrero, meanwhile, an estimated 1,000 members of the Guerrero State Union of Peoples Organizations (UPOEG) swept into the Ocotito Valley between Acapulco and the state capital of Chilpancingo January 23, occupying 8 towns and initially detaining 10 alleged delinquents.

Unlike the self-defense groups in the Tierra Caliente that have been repeatedly photographed with automatic weapons, which under Mexican law are reserved for the exclusive use of the armed forces, the UPOEG forces were armed with shotguns, .22 rifles and small pistols, some of them reportedly homemade. The UPOEG lost no time in forming three new community police units in El Ocotito –two made up of men and one of women.

As in the Tierra Caliente, residents of the Octotito Valley are rebelling against insecurity, extortion and violence, in their case at the hands of an offshoot of the old Beltran Leyva cartel.

The Octotito Valley is also the site of an industrial park designed by the state government to bring development to a state largely dependent on tourism and illicit drug revenues.

Early last year, the UPOEG began forming self-defense groups in the Costa Chica region of Guerrero, an area some distance from the organization’s latest incursion.

Now claiming a force of 6,000 men and women-and growing- the UPOEG is part of a state citizen security and community policing system that is recognized and supported by the administration of Governor Angel Aguirre Rivero.

But frictions between Aguirre’s administration and the UPOEG have become increasingly evident. Reacting to news from the Octotito Valley, the governor cautioned against taking justice into one’s own hands. “We live in a state with the rule of law and institutions,” Aguirre insisted.

On Sunday, January 26, more than 2,000 people, mainly women and children, marched in El Ocotito in support of the UPOEG.

“This is the emancipation of the people of the Ocotito Valley” and “Aguirre Rivero, Guerrero turned out too big for your britches,” were among the chants voiced by demonstrators.

Speaking to the mobilization, UPOEG leader Bruno Plácido reiterated his stance that the movement wasn’t against the government, but that fundamental changes in governance and better cooperation between the citizenry and authorities were urgently needed. Organized crime was the wrong term to describe what was plaguing Guerrero and Mexico, Plácido said. A better definition, the self-defense movement leader insisted, would be “tolerated delinquency.”

The Mexican people, Plácido contended, were wedged between two governments: “the one that charges taxes and raises your gasoline prices and the one that constitutes the underworld.”

In important senses, the UPOEG and other community policing initiatives in Guerrero have a more developed agenda than the Tierra Caliente groups in Michoacan- at least until now.

Campaigning for social and economic development, the UPOEG joined with other social organizations in a January 25 march in Tlapa, Guerrero, against high electricity rates.

Tensions are also on the rise between the UPOEG and the Mexican army, which in contrast has been very tolerant and even tactically supportive of the Tierra Caliente self-defense forces. The reported arrest of two self-defense members by the army January 27 immediately sparked a community protest and highway blockade in El Ocotito that temporarily prevented a military convoy from moving. On January 28, the UPOEG advanced from the Octotito Valley and took three towns including Mazatlan, which is located only 6 miles from Chilpancingo.

Submerged in a familiar spiral of extortion, kidnappings and executions, Chilpancingo could even witness a self-defense uprising, according to some residents and UPOEG leaders.

Businessmen in Chilpancingo delivered an ultimatum this week to all three levels of government, demanding the reestablishment of order. Otherwise, the business leaders warned, they would support the entrance of the UPOEG self-defense forces into the state capital.

“We only want to live in peace,” insisted business leader Pioquinto Damian Huato.

Only a day after making the comments, gunmen attacked Damian and his family while riding in a vehicle. Damian emerged unscathed, but a son was wounded and daughter-in-law Laura Rosas Brito killed.

Separately, Damian’s house was shot up. Damian blamed the mayor of Chilpancingo, whom he had previously accused of complicity with organized crime, for the violence against his family.

As FNS was going to press, an explosive situation was reported around the Guerrero state capital, with a major military mobilization underway and self-defense forces on the outskirts of Chilpancingo.

The Mexican army was also very active in Puebla this month after news broke of the formation of yet another self-defense organization, this one based in the indigenous communities of Tehuacán and the Sierra Negra. As January crawled to a close, the army had reportedly moved into ten communities in Puebla. Some local political leaders criticized the efforts to establish a self-defense group, claiming their localities were tranquil and without major problems.

Francisco Alfaro Rodriguez, identified as the leader of the incipient self-defense group linked to a social organization, the Common Front for Peaceful Civil Resistance, had a different take on the public safety situation. “There have been robberies committed by the municipal police,” Alfaro said. “This is a solid denunciation. The people are fed-up.”

In Michoacan, a thousand questions hang in the air.

Dionisio “El Tío” Loya Plancarte, a Knights Templar leader who gained social media fame last year after he appeared in a YouTube video challenging self-defense leader Hipolito Mora to a duel, was detained by the Mexican military only hours before the government and Tierra Caliente self-defense forces signed this week’s 8-point agreement in the town of Tepaltepec. Noticeably, the government did not release a video or photo of the wanted man’s detention on the day of his capture.

The January 27 accord institutionalizes the self-defense movement by allowing its members to join a reactivated rural police force, a system first created in the 19th century as an adjunct to the army during the presidency of Benito Juarez and expanded in the 1930s under the administration of President Lazaro Cardenas. The prospective members will have to turn their names over to the Mexican armed forces, as well as register their weapons with the military.

The agreement, which contains no timelines or clear mechanisms for independent monitoring, also pledges to audit local governments, alternate justice system officials and punish officials who have committed proven crimes.

“We have the same purpose, to end crime,” said Alfredo Castillo, President Pena Nieto’s special commissioner for Michoacan.

On a parallel front, Castillo will oversee the infusion of about $300 million in new government social and economic spending for Michoacán.

While the Tepaltepec agreement does not immediately change conditions on the ground, Hipolito Mora was among self-defense leaders signing on to the accord that gave a “vote of confidence” to the government. Nevertheless, Mora added, his forces would retain their weapons until all the leaders of the Knights Templar were in custody and the state cleaned-up of criminals.

Although the Knights Templar is clearly on the defensive after having suffered the detention of El Tío and other members, most of its leaders are still at large and analysts consider the well-armed organization intact. Additionally, Fausto Vallejo, the controversial state governor, remains in office along with his top officials.

Yet even as the ink on the January 27 agreement was barely dry, about 200 members of the self-defense forces occupied the town of Los Reyes and set up checkpoints.

On January 28, a new self-defense movement separate from the Tierra Caliente forces had reportedly popped up in a half-dozen communities near Yurecuaro on the Michoacan-Jalisco state line.

Interviewed in Puebla, Gustavo Madero, national leader of the conservative National Action Party (PAN), said self-defense groups now existed in 11 states, or a third of the country, reflecting a “very grave” security panorama and a “great institutional crisis” of the state.

“There are very strong accusations of corruption, infiltration, and lack of action and authority on the part of local authorities that have to be attended,” Madero said.

In the absence of state action, the former PAN senator from Chihuahua said, Mexicans will look for alternatives that, while maybe illegal or unconstitutional, are viewed as “necessary for defending their patrimonies, their families, their lives and their health.”

In remarks made while on a visit to Chiapas, Bishop Raul Vera of Saltillo, Coahuila, said contemporary developments exposed the utter failure of the government’s anti-crime campaign.

“Corruption is worse by the day..,” Bishop Vera declared, contending that the government needed to get serious about addressing insecurity and citizen grievances or the nation could “wind up in a civil war.”

————————————————————————-

Originally Published by New Mexico State University, on the

Frontera NorteSur page, January 29, 2014

For Sources see: http://fnsnews.nmsu.edu/mexicos-armed-self-defense-forces-surge/

Chinese iron trade fuels port clash with Mexican drug cartel

Chinese iron trade fuels port clash with Mexican drug cartel

By Dave Graham

LAZARO CARDENAS, Mexico Jan 1 (Reuters) – When the leaders of Mexico and China met last summer, there was much talk of the need to deepen trade between their nations. Down on Mexico’s Pacific coast, a drug gang was already making it a reality.

The Knights Templar (Caballeros Templarios) cartel, steadily diversifying into other businesses, became so successful at exporting iron ore to China that the Mexican Navy in November had to move in and take over the port in Lazaro Cardenas, a city that has become one of the gang’s main cash generators.

This steelmaking center, drug smuggling hot spot and home of a rapidly growing container port in the western state of Michoacan occupies a strategic position on the Pacific coast, making it a natural gateway for burgeoning trade with China.

Lazaro Cardenas opened to container traffic just a decade ago, and with a harbor deep enough to berth the world’s largest ships, it already aims to compete with Los Angeles to handle Asian goods bound for the U.S. market.

But that future is in doubt unless the government can restore order and win its struggle with the Knights Templar, who took their name from a medieval military order that protected Christian pilgrims during the Crusades.

Mexico’s biggest producer of iron ore, Michoacan state is a magnet for Chinese traders feeding demand for steel in their homeland. But the mines also created an opportunity for criminal gangs, such as the Knights Templar, looking to broaden their revenue base into more legitimate businesses.

“The mines were mercilessly exploited, and the ore was leaving. But not in rafts or launches – it was going via the port, through customs, on ships,” said Michoachán’s governor, Fausto Vallejo, soon after the Navy occupied the port on Nov. 4.

Already a thriving criminal enterprise adept at corrupting local officials and squeezing payments from businesses, developers and farmers, the Knights took to mining with aplomb, according to entrepreneurs and miners working around the port.

Hidden behind mountain roads about an hour from Lazaro Cardenas, one small town mustered hundreds of trucks this year to lead the gang’s scramble to the port, a local miner said.

That town – Arteaga – is the birthplace of Servando Gomez, the former school- teacher who leads the Knights Templar.

Gomez understood the potential of Lazaro Cardenas, which was a village best known for its coconuts until the government decided to build a steelworks there 40 years ago.

The gang’s trucks sped around Michoacán’s iron mines to supply Chinese buyers, helping to push ore exports to 4 million tons by October from 1-1.5 million tons a year previously.

Their business rests on several pillars, according to accounts of local officials, miners and entrepreneurs.

Firstly, the Knights controlled how the ore moved, having imposed protection charges on local transport unions after becoming the dominant gang in the city a few years ago.

It also helped local prospectors stake claims to mine areas either unclaimed by others or beyond the control of the existing concession-holders. Then the Knights took their cut.

Finally, the gang pressured customs officials to ensure the ore passed through the port smoothly.

“Most of the groups mining are Knights Templar or belong to them. They have the whole chain,” a local official told Reuters.

Fueled by the appetite of Chinese buyers, about half the mining in the area was done without proper permits this year, said the official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Those who talk openly can pay dearly. In April, an official at steel maker ArcelorMittal who local businessmen said had reported illegal mining to authorities was shot dead.

One prospector from Arteaga, who asked to remain anonymous, said he ran a mine selling unprocessed iron ore to Chinese traders for $32 per ton, giving him a profit of about $5-7 per ton. By the time it reached China, the buyers could expect to sell the ore for a profit of around $15 per ton, he estimated.

Because the Knights Templar control much of the local iron supply, the gang has pressured Chinese buyers to purchase ore from them or face reprisals, said a Mexican government security official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The combination of organized crime and Chinese buying of Mexican iron ore poses a problem for President Enrique Pena Nieto, who has gone out of his way to cultivate ties with China.

China’s President Xi Jinping has been in office only since March, but Pena Nieto has already met him three times. In June, Pena Nieto welcomed Xi to Mexico, signing a string of economic cooperation deals. But at the top of the agenda was how to narrow the massive trade imbalance between the two nations.

Bilateral trade was worth $62.7 billion in 2012, up from just $431 million two decades ago, Mexican data shows. But 90 percent is accounted for by Chinese exports to Mexico, most of it goods such as computers and component parts.

CHAOS, LOCKDOWN, MORE CHAOS

Much of that trade goes directly through Lazaro Cardenas.

In 2012, it had the biggest rise in traffic in North America’s 20 top container ports, handling 1.2 million 20-foot equivalent units, or teus.

Most of the port is still a dusty plain above which birds of prey soar in stifling heat. In a few years, though, projects started by Maersk-unit APM Terminals and Hutchison Port Holdings could expand its capacity to about 8 million teus – the amount moved in 2012 by the continent’s top container hub, Los Angeles.

But Michoacán is not California.

Seven years ago, then-President Felipe Calderon began a nationwide crackdown on organized crime in Michoacán, sending in the army to tackle increasingly violent drug cartels.

Over 80,000 [1] people have since died in gang-related killings across Mexico, and assurances Pena Nieto gave that he would stop the rot when he took power a year ago are wearing thin.

Although parts of Mexico have become safer since Pena Nieto took office, Michoacan has fallen into even more chaos.

Over half of the state lives in poverty. Traditional work like resin production is dying out due to competition from China and elsewhere. That creates new recruits for organized crime.

In October, a local bishop likened Michoacán to a failed state. A few days later, assailants temporarily knocked out power for hundreds of thousands in the state with a string of attacks on installations of the national electricity utility.

Many blamed the Knights, though signs posted in Michoacan accused a small rival gang of staging the attack.

The Navy took over the port authority and reinforced Lazaro Cardenas shortly afterward. All the local police and customs officials were initially suspended and the caravans of trucks carting ore started to thin out.

But the lull is unlikely to last unless the government can regain control of the city beyond the port gates and open up mining to legitimate prospectors not controlled by the gang.

Miners complain that the main concession-holders such as ArcelorMittal, which did not respond to requests for comment, use only a fraction of their land and are reluctant to let others mine it. The Knights have turned that dispute into money.

Days after the Navy moved in, state governor Vallejo said criminal enterprise around Lazaro Cardenas could be worth up to $2 billion a year – or about half Michoacán’s 2012 budget.

‘EVERYONE IS PAYING’

Some involved in the mining industry say the area has become safer since the Knights Templar started to take control.

But the facts suggest otherwise: government figures show kidnappings in Michoacan reached a record level in 2013, and murders climbed to a 15-year peak.

Gomez has appeared in several YouTube videos trying to portray his Knights Templar as defenders of Michoacán.

In one posted in August, he said the Knights had provided paid protection at the request of avocado farmers but that they did not extort businesses. However, he also conceded that some “foolish” members of his gang probably had engaged in extortion.

The Knights’ power in Lazaro Cardenas is often subtle.

Unlike parts of northern Mexico living under the threat of violence, the restaurants, taco stands and bars on the city’s main palm-lined boulevard are alive with people as night falls.

Some residents say they are not squeezed by the cartel, and big companies say they can operate without fear of extortion.

“We don’t pay a cent to anyone,” said Jose Zozaya, head of Kansas City Southern Mexico, which operates the rail link that connects the port with the United States.

But others quickly vent their anger about the Knights.

“Everyone is paying, but they won’t tell you,” said a local entrepreneur. “The people here are destroyed.”

The port is no stranger to crime, and during Calderon’s presidency it became a big entry point for chemicals from China and other parts of Asia used to make methamphetamine. Some locals say chemicals have even been used to pay gangs for the iron ore.

Asked if Mexico had discussed the iron ore issue with Beijing, a senior government official said: “The Chinese government doesn’t always know what the companies are doing. The occupation of the port … was the control measure adopted.”

Hua Chunying, a Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman, said she was unaware of the situation in Lazaro Cardenas, adding: “But I can tell you that the Chinese government has consistently educated and asked Chinese companies to respect the law in other countries when they carry out business and trade cooperation.”

Successful Chinese firms are growing quickly in the region.

Since setting up in 2009, Desarrollo Minero Unificado de Mexico (DMU), a Chinese iron mining company in Lazaro Cardenas, has gone from three employees to 600 nationwide, nearly all of them Mexicans, Director General Luis Lu told Reuters.

With more than 30 concessions, Lu said his company mined all of its own iron and had not had any trouble with organized crime. He said he could not say how other Chinese firms fared.

Still, Chinese success in Michoacán has caused friction with the Knights Templar. In the August YouTube video, gang leader Gomez had some strong words for them.

“We have an excessive invasion of Chinese. An excess of Chinese,” he said, surrounded by armed men. “It may suit the interests of various corporations, I don’t know. But they’re here with us now. And these people have their mafias too.”

—————————————————————————————

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/01/01/mexico-drugs-port-idUSL2N0JB02E20140101

Raúl Zibechi: When the Peripheries Move

WHEN THE PERIPHERIES MOVE AROUND

Raúl Zibechi

Groups of youths from 15 to 20 years old are self-convoking in the shopping centers of Brazil, above all in São Paulo, although the practice is extending throughout the country, to walk around, have fun and to sing and dance ostentation funk, a genre derived from funk carioca that exalts consumption, luxury brands, money and pleasure. They are youths that come from the São Paulo peripheries, poor and, therefore, Black.

On December 7, some 6,000 came together at the Itaquera [1] Metro Shopping Center, habitually frequented by families of the periphery. On the 14th several hundred entered Guarulhos International Shopping Center dancing and shouting, and although there were no damages, robberies, or consumption of drugs, the police repressed them again and carried 23 off arrested for no reason.

The flash mobs (rolezinhos) were held for several years on the part of students or fans of musicians or sports celebrities. The University of São Paulo (USP) economics students held one of the most famous rolezinhos since 2007 in the Eldorado Shopping Center. They were never repressed, not even made uncomfortable by security, although they came en masse and without prior warning. They shouted offenses and when some of them went up to the tables, security politely asked them to get down (Folha de São Paulo, January 21, 2014).

To the contrary, when dealing with youths from the peripheries, property owners of the commercial centers find protection in court decisions, sellers close businesses and clients insult them and treat them like delinquents. They create the climate ripe for repression from the Military Police, one of the most deadly in the world.

Journalist Eliane Brum asks: “Why are the Black youth from the peripheries of Greater São Paulo being criminalized?” (El País-Brasil, December 23, 2013). In the national imaginary, she maintains, for the poor youths to have fun outside the limits of the ghetto and to desire consumer objects is something offensive, because “the shopping centers were constructed to keep them out.” Not just the shopping centers: the whole society leaves them out.

Those from below always move around, show themselves, if it is only to come out of the periphery using the same codes as the capitalist society. They are discriminated against and beaten up because they are occupying spaces that are not meant for them. In this case, they committed a major crime: not only did they dare to show the same objects as the rich on their dark-skinned bodies, but they also began to occupy spaces-temples sacred to the middle and upper classes.

When the peripheries move around, they uncover the power relations that in daily life appear covered by inertias, beliefs, media influence, religion and ideologies. The first thing that they have shown is the texture of power: the role of the repressive apparatuses and of the justice (system) as servants of capital; how racism and classism are interwoven as the axes for oppression and exploitation; the role of the city as a space for real estate speculation, in other words, for urban extractivism. [2]

The second thing is the intransigence of the middle classes, in particular that sector of new consumers that recently left poverty thanks to economic growth because of the high price of commodities and social assistance policies. There is a generational problem here: the youths that make flash mobs are children of those who they accuse of being robbers and they beat them with their clubs. They belong to the same social sector, but few are grateful and they want more.

The third question is related to us. I consulted a friend and member of the Passe Livre Movement [3] (N de la R: he travels free on public transportation), who played a relevant role in the June demonstrations, to ask his opinion about what’s happening. Annoyed, he told me that they are tired of being interpreted by others, above all people that do not have the least relationship with their struggles but establish themselves as analysts, thereby establishing a relationship of colonial power, subject-object, in that second place always falls to those from below.

In a few days an infinity of analyses were triggered that sought to explain what the youths do, often kicking it far from the goal. Even more damaging are the discourses that individuals and groups on the left have been issuing. During the June demonstrations when they were playing for the (FIFA) Confederations Cup, they labeled the mobilizations as provocations that can favor the right; an absurd calculation, but efficient for isolating and de-mobilizing.

With respect to the flash mobs they affirm that they are “uncommitted, de-politicized actions,” which in the end only seek to be integrated through consumption. Although an age prejudice also appears here: the older generations (to which I belong) usually recite sermons on what is correct and what is deviation to the youths, with the same air of superiority that the party cadres admonished us in 1969 and 1970.

But what appears more serious is the mystification of the social struggles. The workers of Saint Petersburg that championed the 1905 Revolution and created the first soviets were not politicized by the speeches and texts of Lenin or Trotsky, but by the Czar’s bullets when they marched to the Winter Palace to deliver him a petition, headed by Father Gapon, who was working for the secret police. Bloody Sunday politicized the Russian workers. Something similar happened with the women’s march to Versailles in October 1789, which sealed the end of the monarchy.

A profound confusion exists about the role of ideologies and leaders in revolutions and in the processes of change. Pure spontaneity, which does not exist according to Gramsci, does not lead very far, often to bloody failures. But, “conscious and external direction” does not guaranty good results. We can attempt to learn together, above all when the peripheries move around and place our old wisdoms in question.

Translators Notes:

[1] The Itaquera Stadium is one of the new stadiums Brazil is constructing for the World Cup this summer. It is located in São Paulo and, although not yet completed, has a Metro (rapid transit) stop and a shopping center next door.

[2] Extractivism is Zibechi’s term for accumulation by dispossession. In Mexico the word despojo is used for dispossession.

[3] The Passe Livre (Free Fare) Movement is an autonomous Brazilian movement that advocates free public transportation.

———————————————————–

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada

Friday, January 24, 2014

Translation: Chiapas Support Committee

En español: http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2014/01/24/opinion/019a1pol

Mexico: Drug War Meltdown

MEXICO: THE POLITICS OF A STATE MELTDOWN

As a massive federal police and military deployment gains momentum in the Mexican state of Michoacan, polemics and debate shroud the first major such operation undertaken by the administration of President Enrique Pena Nieto.

At stake in the campaign is not only the reassertion of state power, but also the strategic control of the Pacific coastal port of Lazaro Cardenas, one of the key portals of the Asia/NAFTA economy, as well as the productive mountains and farmlands whose products and people travel a network of highways leading across Mexico and into the United States.

With upwards of 10,000 federal forces now deployed, along with perhaps equal numbers of gunmen from the Knights Templar syndicate and opposing, civilian self-defense groups, Michoacan is the scene of a “low-intensity war” that will soon witness drones, massive telecommunications intercepts and commando operations, predicted Gerardo Rodriguez Sanchez Lara, director of the private Mexican Human Security firm.

On Mexican television, commentators openly compare Michoacan with Syria, Colombia and the balkanized states of the former Yugoslavia.

Defining Michoacan a “failed state” in all senses, pundit Eduardo Healy called for considering the suspension of civil liberties. He also lashed out against the state’s “out-of-control” teachers, who have been waging a year long struggle against the Pena Nieto administration’s education reform.

Michoacan has very active and militant teacher and other social movements, and it remains to be seen if civil society organizations will now be in the cross-hairs of intensified government operations officially targeted at organized crime.

While the Mexican government has yet to adopt the measures advocated by Healy, proposals for an iron-fist strategy are part of the public discourse.

A deeper analysis of the Michoacan crisis reveals a distinctly Mexican one with strong if not overriding U.S. influences that have integrated the local economy into a export flow of products and people northward to the great market beyond the Rio Bravo.

In a recent column, Gerardo Rodriguez noted that the crisis in Michoacan finds its historic origins in “problems of territorial control among families and caciques (rural bosses) that dispute the natural richness and political control of its communities since the colonial epoch.”

Politically, the crisis taints all the major Mexican political parties, which either had a direct hand in criminal activities or tolerated the emergence of a parallel state under their noses, especially in the post-NAFTA era when Lazaro Cardenas emerged as a prize Pacific trade hub while a historic decline of the legal rural economy deepened.

“Some federal resources began to come to the Apatzingan Valley (Michoacan) barely five years ago,” a resident was quoted in the Mexican press. “Previously, only illicit money moved the region. The drug traffickers not only invested, but they avoided kidnappings, robberies and extortions. They were a government over the government, and they benefited everyone.”

Since 2000, the power of organized crime has steadily overtaken state authority. The decomposition of state power occurred during two presidential administrations headed by the National Action Party (PAN) and one by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), two state governments dominated by the PRI and two by the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), and municipal governments of various political stripes.

Although former Mexican President Vicente Fox continues berating his successor and fellow Panista (PAN member), Michoacan son Felipe Calderon, for the security disaster, a more objective review of the historical record shows that narco-violence surged in Michoacan and other parts of the nation precisely during the Fox administration, which allegedly colluded in or covered up the violence, according to numerous reports.

Under Fox’s watch, a new cartel, La Familia Michoacana, from which the Knights Templar later arose, formed and quickly consolidated an unprecedented degree of power in a state where illicit drug cultivation and trafficking had long existed but was kept under control to an extent.

“The Family took over entire city governments,” columnist and analyst Jenaro Villamil recently wrote. “It bought mayors, legislative candidates, and organized the direct extortion of hundreds of merchants.” Michoacan residents, in essence, were burdened with a double taxation system: one payment to the weak, official government and another one to a strong, unofficial one.

Not surprisingly, many residents abandoned the state, an entity already considered one of the biggest migrant-expelling regions of Mexico. According to a recent media report, hundreds of applications for U.S. political asylum are pending from the conflictive Tierra Caliente region of Michoacan.

“People are arriving every day, ever since the violence began there,” a California resident identified as Hector said. The 14-year resident of the Golden State said a dozen relatives seeking refuge had crossed over to the U.S. in recent months. Nearly a decade later, a combination of finger pointing, handwringing, bravado, and mea culpas are emanating from the governing elite, with burning constitutional, political and public safety questions on the table.

Although the Calderon administration oversaw the detention of dozens of mayors accused of complicity with organized crime in the ill-fated “Michoacanzo” of 2009, the cases fell apart and no other high officials were held accountable for a meltdown of public safety and governance.

Some members of the PAN and PRD parties have clamored for the federal Congress and President dissolve the Michoacan state government, a power permitted under the Mexican Constitution and which has been used in the past, most notably in the neighboring state of Guerrero.

But any movement toward dissolving the PRI-ruled state government was forestalled when President Pena Nieto designated Alfredo Castillo Cervantes the special commissioner for Michoacan this month. The 38-year-old Castillo was handed the heady tasks of restoring order and reconstructing the tattered social fabric in the western state of almost five million people.

While Castillo’s appointment saved face for Pena Nieto’s PRI party and embattled Michoacan Governor Fausto Vallejo, whose 2011 election campaign was allegedly supported by the Knights Templar, Castillo’s mission effectively puts Mexico City in the political driver’s seat. Castillo, however, is careful to guard political forms and insists he is working in coordination with Vallejo and other political leaders, not displacing them. Otherwise, the old image of a heavy-handed Mexico City trampling over an unruly province could enter the public perception of the crisis.

“In reality, the President and the PRI recognize that the powers in Michoacan have practically disappeared, but they don’t say it openly,” said PAN Senator Salvador Vega Casillas, who added that Vallejo should resign so the Michoacan state lawmakers can elect a new governor to serve out the constitutional term.

In a similar vein, PRD Senator Dolores Padierna questioned the constitutionality of Castillo’s powers, urging that the formal dissolution of the state government proceed. The Mexico City senator’s proposal, however, is unlikely to gain traction.

The eyes of the nation are on Castillo. A lawyer by profession but a troubleshooter by trade, Castillo is a man of the state, having served both PRI and PAN administrations in different capacities.

During the Fox administration, Castillo was an advisor to Attorney General Rafael Macedo de la Concha, an army general who eventually resigned after Fox administration attempts to force then-Mexico City Mayor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador from office backfired and provoked massive demonstrations.

Last year, Castillo helped prepare the legal case for the Pena Nieto administration against longtime power broker and national teachers’ union leader Esther Gordillo, who is now imprisoned on corruption charges.

Now, as special commissioner for Michoacan, Castillo is tasked with restoring some semblance of order to a state where dozens of security agencies, cartels and community self-defense organizations make the place an armed camp.

Together with Interior Secretary Miguel Osorio Chong, Castillo has the future of the Pena Nieto administration in his hands. Ironically, Michoacan is where Felipe Calderon unleashed his heavily criticized “drug war,” and events in the impoverished state now also stand out as a defining moment for Calderon’s successor.

It’s too early to predict how the situation on the ground will evolve, but if Pena Nieto’s administration meets public demands of detaining Knights Templar leaders, the president’s fortunes will certainly benefit.

Hipolito Mora, leader of the La Ruana self-defense group which formed to expel the Knights Templar in a citizen uprising, praised the federal deployment but said his organization would keep its arms for a “little while longer,” or at least until the capos are arrested.

As the federal operation entered its second week, traffic was reported flowing on previously dangerous highways and classes had reportedly resumed in Apatzingan, epicenter of the violence. Nonetheless, a fed-up public expects significant changes and actions, and very soon.

The employees of an Apatzingan pharmacy that suffered an arson attack last week staged a march January 20 to demand genuine security. Cristian Pineda, spokesman for the workers, said continued insecurity was causing economic hardship for the locals.

“It’s not just us,” Pineda said. “Many people in the city can’t work and don’t have stable employment, due to the problems they are suffering from the insecurity.”

Columnist Julio Hernandez Lopez characterized the current situation as a kind of win-win truce in which the government flexed its power, the self-defense forces held on to their weapons and the Knights Templar, though suffering some detentions and dislocations, stayed largely intact.

“The state government has been practically folded and Osorio Chong, wagering his future political capital, is winning until now-at least in terms of appearances,” Hernandez wrote.

———————————————-

Sources: Teleformula, January 20, 2014. El Universal, January 20, 2014. Article by Julian Sanchez. CNN en Espanol, January 19, 2014. Tribuna de la Bahia/Agencia Reforma, January 17, 18, 19, 2014. Articles by Claudia Guerrero, Adan Garcia, Angel Villarno, Benito Jimenez, Gerardo Rodriguez Sanchez Lara, and editorial staff.

Televisa, January 17, 2013. La Jornada, January 16 and 20, 2014. Articles by Julio Hernandez Lopez and Arturo Cano. Proceso/Apro, December 29, 2013; January 9, 12, 14, 16, 17, 2014. Articles by Ezequiel Flores Contreras, Jose Gil Olmos, Veronica Espinosa, Jenaro Villamil, and editorial staff.

——————————————————–

Published January 20, 2014 by Frontera NorteSur

New Mexico State University

http://fnsnews.nmsu.edu/mexico-the-politics-of-a-state-meltdown/