By: Hermann Bellinghausen

AFFIDAVIT BEFORE THE INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS (REF.: CDH-5-2022/027). TESTIMONY FOR GONZÁLEZ MÉNDEZ V. MEXICO

May 2023

I base this testimony on my daily experience as a reporter, permanent envoy of the national newspaper La Jornada to cover the social and political movement unleashed on the new year of 1994 in all the indigenous regions of Chiapas. I lived in the city of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, in the Altos region of the state, from the first week of January 1994 until mid-2014. In that period, especially the first 15 years of my stay, I also spent time in various communities of the Maya villages in the Lacandón Jungle, the Highlands and the North Zone. In some Tojolabal, Tseltal, Tsotsil and Chol communities I came to feel at home, theirs.

My work was to listen to them, witness their events and tragedies, document the evolution of their autonomy and the underground war waged against thousands of communities by the Mexican State, its Armed Forces, its intelligence services, its unofficial versions of the facts, the serious aggressions against the native population of the Chiapas mountains, of Maya and Zoque lineages. I reported this daily in reports, chronicles and informative notes published in La Jornada and often translated into other languages and disseminated abroad.

The movement of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), initially warlike, soon became peaceful, although in resistance, thanks to a fragile truce. The covert and repressive actions of the Mexican Army and the national, state and municipal police corporations put it at risk again and again.

The extension and coherence of the Zapatista movement, composed practically exclusively of indigenous people, with very precise demands, expressed since the first of January 1994 in the Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, was surprising and unusual. Always showing rigorous discipline and sensible control of its firepower, the EZLN had organized support bases in all the official municipalities of exclusively or mostly indigenous population in Chiapas.

The conflict occupied centrally the national political agenda and the government of Mexico. Locked in a chain of denials, falsehoods and half-truths, the State aimed to contain and destroy the rebel movement from the first days of 1994, even during the presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari, and more clearly and profoundly since the beginning of the presidency of Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León, in December of the same year.

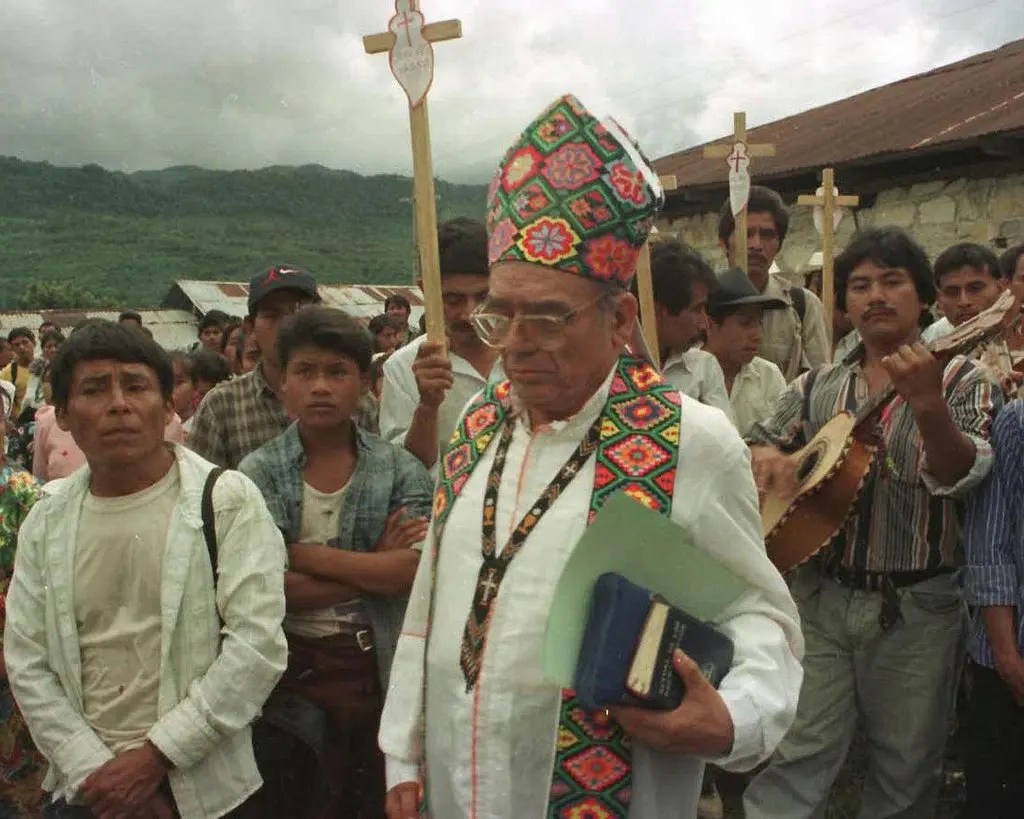

Before arriving at the central point of this testimony, which is the forced disappearance in the municipal capital of Sabanilla of Antonio González Méndez, Chol and EZLN support base, on January 18, 1999, it is worth mentioning how the undeclared, not recognized by the authorities lived daily, the covert war against the Zapatista movement and sympathetic but peaceful organizations close to the Diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, in charge of Bishop Samuel Ruiz García. The latter frequently suffered massacres, disappearances and displacement. But the obvious objective was the Zapatista support bases, seeking to provoke armed responses from the EZLN and annul the truce decreed by the Congress of the Union with the Law for Dialogue, Conciliation and Dignified Peace in Chiapas, in March 1995. Just a month earlier, on February 9, President Zedillo had ordered the military occupation of the newly declared Zapatista autonomous municipalities; that is, almost all the indigenous regions of Chiapas.

The Mexican State, through the Federal Army, launched the Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan (released on January 3, 1998); This establishes the counterinsurgency offensive that will define subsequent events. The true implications of the strategy would be seen over the next five years.

The militarization was direct in dozens of rebel communities, or very pro-government and associated mostly with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), still then hegemonic, camouflaged with the national State, the government of Chiapas and the Armed Forces. For those of us who observed the so-called conflict constantly and in person, a drastic change in the way the state sought to “solve” the conflict became evident. Entering “the heart and soul” of the inhabitants, and “taking the water away from the guerrilla fish,” as dictated by the Pentagon counterinsurgency manuals applied in Guatemala and Vietnam.

Although these strategies were sought to be implemented throughout the area of influence of Zapatismo, not all of them caught on (for example, in the cañadas (canyons) of the Lacandón Jungle). Where the “civilian armed groups” first manifested themselves clearly, an eternal euphemism for paramilitaries, was in the Northern Zone of Chiapas, inhabited mostly by Chol Mayas. In the municipalities of Tila, Sabanilla, Salto de Agua and Tumbalá, the official hegemony of the PRI was transformed into the real predominance of the organization Development, Peace and Justice, which soon began its violent actions.

Some of its top leaders had criminal records in the region since the previous decade; now they became obvious allies of the military command that occupied municipal capitals, roads and indigenous villages. The municipal capitals of Tila and Sabanilla were controlled by Paz y Justicia; the respective parish priests lived practically besieged in their temples and that of Sabanilla, a Spanish citizen, would soon be expelled from the country by the Mexican government.

In other rebel regions, despite militarization, the public presence of the Zapatistas was maintained, who openly guarded territories in resistance, organized around five “Aguascalientes” (Zapatista meeting and self-government centers). In the Northern Zone this was much more difficult, especially after 1995. The violence of the armed civilian group was constantly manifested. Communities in Tila and Sabanilla [municipalities] had to move, fleeing from the looting, rapes of women and executions, under the impassive gaze of federal troops and police forces.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has knowledge of the important reports published by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center and other defense organisms (including the United Nations Rapporteur on Indigenous Peoples). The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) itself has sent in-person observers. There are many details, testimonies and documentation of the events that occurred during the covert war, also called low intensity, “delegated” to armed groups not military or belonging to the federal army.

In August 1995, the San Andrés Larráinzar Dialogues began between the Mexican government and the general command of the EZLN, with the mediation of the National Intermediation Commission (CONAI) headed by Bishop Samuel Ruiz García and the assistance of a commission of senators and deputies appointed by the Congress of the Union, the Commission of Concord and Pacification (COCOPA). On more than one occasion, the tense and delicate talks between the rebels and the government were sabotaged by armed attacks in the Northern Zone, burning of hermitages, deaths and disappearances.

By then the North Zone had become difficult to navigate. It was particularly dangerous for civilian observers, human rights defenders and journalists. With its headquarters in Miguel Aleman, a community in Tila, Paz y Justicia spread terror among the Zapatistas and their sympathizers (vaguely identified as members of the Party of the Democratic Revolution and Bishop Ruiz García’s Catholic Church).

When in my journalistic work I visited the communities and camps of displaced persons in Tila and Sabanilla, I tried to enter on one side and leave on the other, so as not to return to the military, and above all Paz y Justicia’s “civilian” checkpoints. I always thought twice about doing those tours. Between 1996 and 2000, on more than one occasion outside observers were assaulted, even shot. Bishop Ruiz García himself was attacked twice; the second, on November 4, 1997, in the company of Raúl Vera, assistant bishop of the diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

One aspect worth mentioning is the closeness, to say the least, of the highest military command in Chiapas, General Mario Renán Castillo, with Paz y Justicia. A graduate of Fort Bragg and a specialist in counterinsurgency practices, he can be considered the architect of the government’s counterinsurgency plan that deliberately militarized and para-militarized indigenous regions with a Zapatista presence. All this is duly documented in reports that the IACHR has known for years.

Mention should also be made of the subsequent para-militarization of Los Altos, in the Tsotsil region. At the beginning of 1997, the presence of a new paramilitary group became widespread in the municipality of Chenalhó, which was never identified under a precise name. As a contagion from the neighboring Northern Zone, armed civilian groups in visible collusion with federal troops and police forces (both to operate and train and for the transfer of weapons) unleashed a chain of aggressions against Zapatista communities and the Las Abejas Civil Society Organization. The Acteal massacre on December 22 of that same year was a tragedy foretold. Unlike what happened in Tila, Sabanilla, and soon Chilón (where the criminal-paramilitary group Los Chinchulines operated), in Chenalhó journalistic observation and documentation by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (CDHFBC) and other independent organizations were continuous; There were even poignant reports on commercial television. It was no use.

As part of the correspondents and envoys of La Jornada, I covered the events of Chenalhó throughout 1997. Ten years later I published the book Acteal, crimen de Estado (Ediciones La Jornada, Mexico, 2008), recapitulating what happened in Chenalhó that year and the following months. The notoriety of the events, in particular the massacre against followers of the pacifist group Las Abejas, did not prevent the State from hiding and denying its responsibility. The application of justice was limited and ultimately betrayed. The armed group was never disarmed, the perpetrators were not punished, and the application of justice against some operators of the Chiapas state government was insufficient.

In 1998, paramilitary violence spread in Los Altos de Chiapas. In the municipality of El Bosque, the criminal group Los Plátanos operated, openly associated with the federal army and the judicial police. They carried out a massacre in the community of Unión Progreso, this one against Zapatista support bases, while the municipal capital, declared autonomous, was violently occupied by the Federal Army, which at the same time carried out another massacre, in the community of Chavajeval. Since 1997, on March 14, the Army and police forces had carried out the massacre of San Pedro Nixtalucum (El Bosque), murdering four Zapatista civilians and displacing 80 Tsotsil families.

In 1998, the MIRA group operated in the Lacandón Jungle, with relative success. In Chilón, Los Chinchulines destroy homes, rob and murder EZLN sympathizers. Also in 1998, the Chiapas government, supported by such unofficial groups, violently “dismantled” the autonomous Zapatista municipalities of San Juan de la Libertad (El Bosque) in Los Altos, Amparo Aguatinta (Las Margaritas) on the border, and Ricardo Flores Magón in the Lacandón Jungle in Ocosingo.

Somehow, during the period, the action of paramilitary groups, always officially denied, was “normalized.” Between 1995 and 2000, in Tila, Sabanilla, Tumbalá and Salto de Agua, murders became recurrent, including mutilation of bodies, forced disappearances, rapes, the destruction of villages and the forced displacement of hundreds of Chol families. The EZLN establishes new towns, on land recovered after the uprising, for its bases in Los Moyos and other communities in Tila and Sabanilla.

There have been 37 documented forced disappearances, 85 extrajudicial executions and some 4,500 people displaced by the paramilitary group Organization Development Peace and Justice in these Chol municipalities. As highlighted in CDHFBC, the situation is known to the IACHR in case 12.901 Rogelio Jiménez López and Others vs. Mexico.

All this relationship serves to give context to the forced disappearance of Antonio González Méndez, thoroughly investigated by the CDHFBC since then, without the case having received the benefit of justice from the authorities to date.

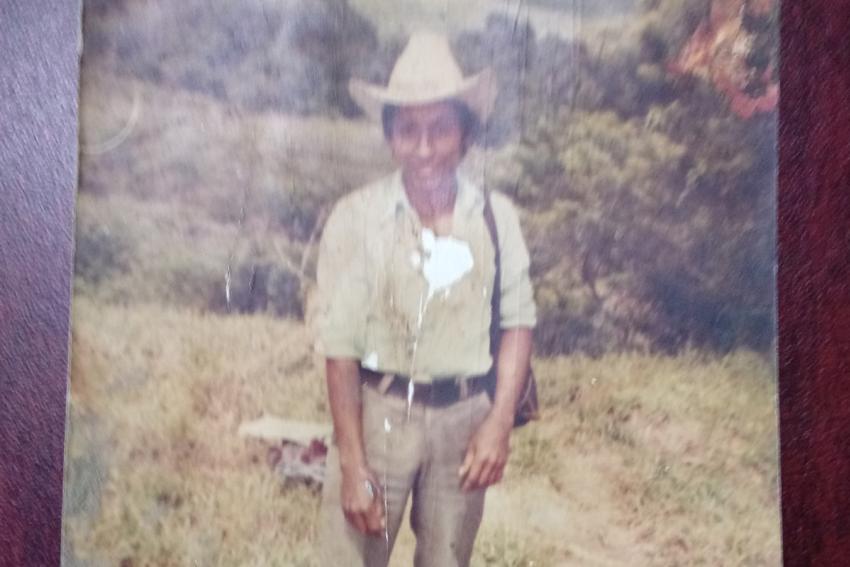

Antonio González Méndez, a member of the EZLN’s support bases, was responsible for the “Arroyo Frío” cooperative store located in the municipal capital of Sabanilla at the time of his disappearance. This made him a visible figure of Zapatismo, in a town that, as it was already settled, was under the control of Paz y Justicia. Its members governed the municipalities of Sabanilla, Tila and Tumbalá. That is, the municipal police and their investigative bodies worked for Paz y Justicia, in turn openly associated with the occupying federal army.

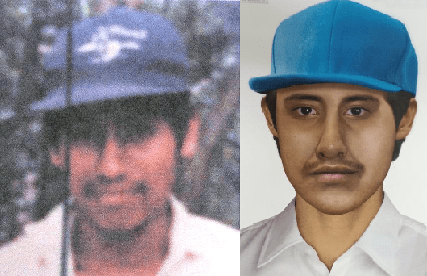

The alleged perpetrator of the disappearance, a member of Paz y Justicia, has been identified. This has not served to clarify Antonio’s disappearance, and even less to provide restorative justice for his family. Here we find, as in dozens, perhaps hundreds of cases, the repetition of impunity as part of the counterinsurgency pattern. The protection of the prosecutors’ offices when the paramilitary groups acted was evident.

It is essential to emphasize that, to date, the federal government maintains a position in which it denies having developed this counterinsurgency strategy. This immovable denial represents a serious obstacle to the resignification of the victims, the search for truth and justice. In order to make progress in the full administration of justice, it is essential that the Mexican State overcome this position that the facts themselves have denied, which has also been amply documented.

I believe that the forced disappearance and the very probable murder of Antonio González Méndez is part of the operation scheme of the Organization Development, Paz y Justicia. It is in fact one of the last episodes of that atrocious five years in the Northern Zone. With the change of government (and ruling party) in the country and in the Chiapas state at the end of 2000, the belligerence of Paz y Justicia decreases, and even more so when the new state government of Pablo Salazar Mendiguchía imprisons some leaders of that organization, although they are never prosecuted or convicted for their participation in the crimes of the paramilitary organization.

In conclusion, I am convinced that the disappearance of Antonio González Méndez is part of the modus operandi established in the Northern Zone of Chiapas by the Development, Paz y Justicia Organization and its allies, with the direct responsibility of the three levels of government. It obeys the guidelines of the Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan, in the same way as the numerous incidents and violent acts that at that time had been occurring against the communities that were in resistance and con structed despite all their autonomy as indigenous peoples.

Originally Published in Spanish. by Ojarasca, Saturday, July 8, 2023, https://ojarasca.jornada.com.mx/2023/07/08/la-guerra-contra-los-pueblos-de-chiapas-9664.html and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee