For many of us who care about and support the Zapatista struggle, the killings in Polhó were both a shock and a realization of how much things have changed in that corner of Chiapas. Reports on the killings left us with more questions than answers.

By: Mary Ann Tenuto-Sánchez

First, a summary of the facts, based on reports from journalists

In the late afternoon and evening of Friday, June 2, 2023, a pick-up truck carrying indigenous people, initially alleged to be from an armed group that “left Polhó”, as well as “several residents” from the sprawling Santa Martha ejido, Chenalhó municipality, in the Chiapas Highlands, drove through the Zapatista town of Polhó, also in the official municipality of Chenalhó. They shot and killed the son of a man who owned the warehouse in which people displaced from Santa Martha are staying. (One article says the owner is renting to them.) Initial press reports about this incident were based on information from the State Attorney General’s Office, which stated that seven people were dead, 6 people displaced from Santa Martha and the warehouse owner’s son. “Residents of the area” said that the aggressors attacked the more than 200 displaced persons from Santa Martha. Reports said there were also 3 people wounded. [1]

The following day, we learned that initial reports about the incidents were not true. The six dead were not from the group displaced from Santa Martha. The information from the State Attorney General’s Office was wrong; The 6 dead were from the group alleged to be the aggressor group, no longer described as an armed group that “left Polhó,” but rather as an armed group named “Los Ratones” (The Mice), presumably also from Santa Martha.

Information regarding the warehouse owner’s son was correct and the report of 3 injured was also correct. When reporters and police agents arrived on the scene, they not only learned that six of the dead were from the alleged aggressor group, they also learned the identities of the dead and injured. The six dead are Gilberto Pérez Gómez, supposedly the head of the group of alleged aggressors, his wife, his son-in-law, his 3-year-old grandson and two of his brothers, who were also his bodyguards. Staff from the Office of the Prosecutor of Indigenous Justice said that the body of Gilberto Pérez Gómez was found lying next to his truck with a high-caliber weapon at his side.

Among the wounded are Amalia and Estela Pérez Gómez, ages 11 and 19, the two daughters of Gilberto Pérez Gómez. They are in a hospital with serious injuries. One of the Santa Martha displaced was also wounded and taken to a hospital. Additional information is that several houses had holes from bullet impacts and an electrical transformer was damaged, thus the area was left without power. [2]

Some background on Polhó

Chenalhó is considered one of the most violent municipalities in Chiapas. [3] It is the municipality where paramilitary violence began to take place in 1997 as part of the Mexican government’s counterinsurgency strategy against the Zapatistas; the paramilitary campesinos were provided guns similar to those given soldiers and those campesinos were trained on how to use them. The violence this produced included house burnings, murders, robberies and rapes. It eventually culminated in the December 22, 1997 massacre of 45 women, men and children in the community of Acteal, also located in Chenalhó, and in approximately 9,000 people fleeing to find shelter in order to save their lives, leaving their homes, crops and belongings behind. That’s why Pedro Faro Navarro of the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) told La Jornada that the current violence in Chenalhó is a legacy of the Mexican government’s counterinsurgency plan (Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan).

The autonomous Zapatista municipality of San Pedro Polhó serves as the municipal government for members of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN, Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) who live in the official government municipality of Chenalhó. Its Caracol is Oventic. The autonomous Zapatista municipal governments operate parallel to the official municipal governments.

The San Pedro Polhó autonomous government took in many of the refugees and provided them with safety, food and shelter for many, many years. The town of Polhó is the autonomous municipal seat. A large majority of those forcibly displaced in 1997 were sheltered in the town of Polhó. Other Zapatista towns accepted the remaining refugees. Chenalhó is so dangerous that some of those who took refuge there in 1997 never returned to their communities of origin. Some folks who were displaced due to the 1997 violence gradually accepted relocation and land from Zapatista municipalities in the jungle. The town of Polhó is just a few miles from Acteal on the asphalt road that runs through Chenalhó municipality.

This writer visited Polhó many times between 1998 and 2008 as a member of the Chiapas Support Committee (CSC), which joined international solidarity groups in efforts to support this Zapatista town full of people forcibly displaced from their homes by paramilitary violence. Those of us who traveled to Chiapas met with members of San Pedro Polhó’s autonomous municipal council many times to discuss conditions in Polhó.

Those displaced from Santa Martha in 2022

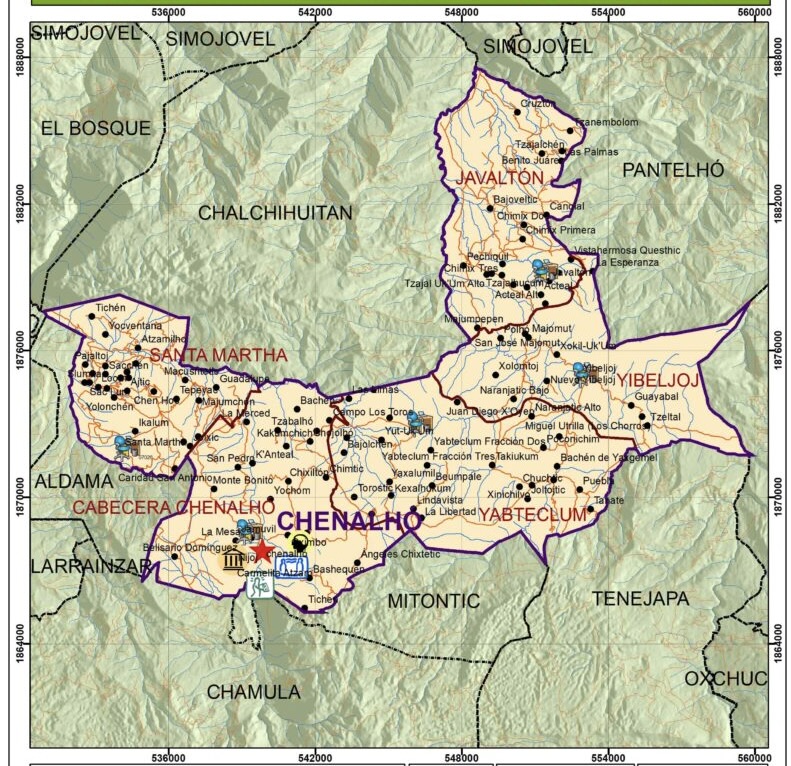

Santa Martha is one of the largest ejidos in Chiapas. There are 22 communities within that ejido. Many of the paramilitaries involved in the 1997 violence and Acteal Massacre were from Santa Martha. The people displaced from Santa Martha in 2022, and currently given refuge in Polhó, are also part of an armed group, the armed group that for years fired shots from high-powered rifles, day after day and night after night, into neighboring communities located in the municipalities of Aldama and Chalchihuitán (see map), in order to gain possession of some of their land. The federal, state and local governments did nothing to stop the shooting. Residents of both Aldama and Chalchihuitán, Zapatista and non-Zapatista alike, were forced to intermittently displace into the mountains when the bullets got too close to them and some lost their land. There were a number of deaths and some people seriously injured as a result of the shooting and forced displacement. Both Aldama and Chalchihuitán gave up some land to Santa Martha. That’s when what the press refers to as “an agrarian dispute” began.

Those who fired their weapons into Aldama and Chalchihuitán apparently were known as “defenders of the land.” According to the Santa Martha displaced, in June 2022, sometime after the lands in Aldama and Chalchihuitán were ceded to Santa Martha, the communal property assembly decided that the newly-acquired lands would be distributed among 195 communal members. According to the Santa Martha ejido authorities, a group of 60 people disagreed with that decision and took up arms and “ambushed” the communal property commission. The men accused of the ambush were taken to the prosecutor’s office, but that office released them and no charges were filed. The dissidents are also accused of murdering a campesino later that same month, so ejido authorities expelled them from their communities, but did not expel their families.

Santa Martha’s ejido authorities said they were prepared to accept the expelled ejido members back into their communities when, on September 29, 2022, the people expelled tried to poison the spring from which the ejido gets its drinking water. They were supposedly caught in the act. On that same date, some of their houses were set on fire and families began to flee. The people who were expelled are accused of killing 6 community members in a fight. They fled with their families. Many who fled ended up in Polhó, but some went to other places where they had relatives who would take them in.

The people displaced from Santa Martha deny the allegations of the Santa Martha authorities. They blame an armed group within Santa Martha and see themselves as victims. Santa Martha ejido authorities did not allow any police or military into the communities where the violence occurred for a week, which suggests that they may have had something to cover up.

To summarize, the people displaced from Santa Martha, now living in Polhó, are the same people who for years fired shots at their neighbors in Aldama and Chalchihuitán, both Zapatista and non-Zapatista, in order to steal a piece of their land.

Some questions and thoughts

The published facts raise various questions, including but not limited to the following: 1) Why did someone tell the Attorney General’s Office that six of the dead were displaced people from Santa Martha and that the armed group was made up of people who “left Polhó?”; 2) If a civilian armed group (Los Ratones) was actually the group of aggressors who intended to attack both the warehouse owner and those displaced from Santa Martha, why did its alleged leader mount such an attack with his wife, daughters and a 3-year-old grandson in the truck? ; and, 3) Assuming they both survive their injuries, what will the two daughters have to say about the incident?

Luis Hernández Navarro may have provided an answer, or at least explanation to questions 1 and 2. In his La Jornada opinion piece, Hernández Navarro describes the June 2 killing as an “ambush” of Gilberto Pérez Gómez and his family, which means that he and his family were not the aggressors and whoever was the source of the false information given to the State Attorney General’s Office, was creating an alibi to deflect blame for the killings. It most likely also means that the people displaced from Santa Martha brought their guns with them when they took refuge in Polhó. It is highly unlikely that an answer to question 3 will ever be made public.

Moreover, we also learn from the Hernández Navarro piece that Gilberto Pérez is the one who killed the wife of El Machete’s commander, meaning that the people displaced from Santa Martha who ambushed and killed Pérez Gómez will now have El Machete’s “protection.”

The overall impression one gets from the facts published about this incident is one of the pervasiveness of armed violence in the official municipality of Chenalhó, and that state and federal authorities permit it to continue. What leaped out to this writer was the report that Santa Martha authorities took the dissidents to the state prosecutor’s office, only to have that office let them go and not investigate further or file charges. This is the same way that both state and federal authorities treated the continuous day and night shooting into Aldama and Chalchituitán. It is the same way the authorities are treating the repeated armed attacks on Zapatista communities in the Moisés y Gandhi region.

The precise issue of state and federal authorities doing nothing to stop the violence against the Zapatista communities was addressed in a national and international statement. Many of us familiar with Chiapas agree with the analysis of the Frayba Human Rights Center that: “We are in a war scenario as a consequence of the abandonment and complicity of the governments, because of which armed attacks have proliferated.”

The authorities just let people kill each other!

The shock of learning that there are displaced people possessing high-powered weapons living in Polhó has still not worn off; It speaks volumes about the pervasiveness of armed violence throughout Chiapas and, in particular, in Chenalhó.

[3] https://chiapas-support.org/2023/03/23/criminality-and-violence-in-the-chiapas-highlands/

Published by the Chiapas Support Committee, a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit and an adherent to the EZLN’s Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle.