Luis Hernández Navarro

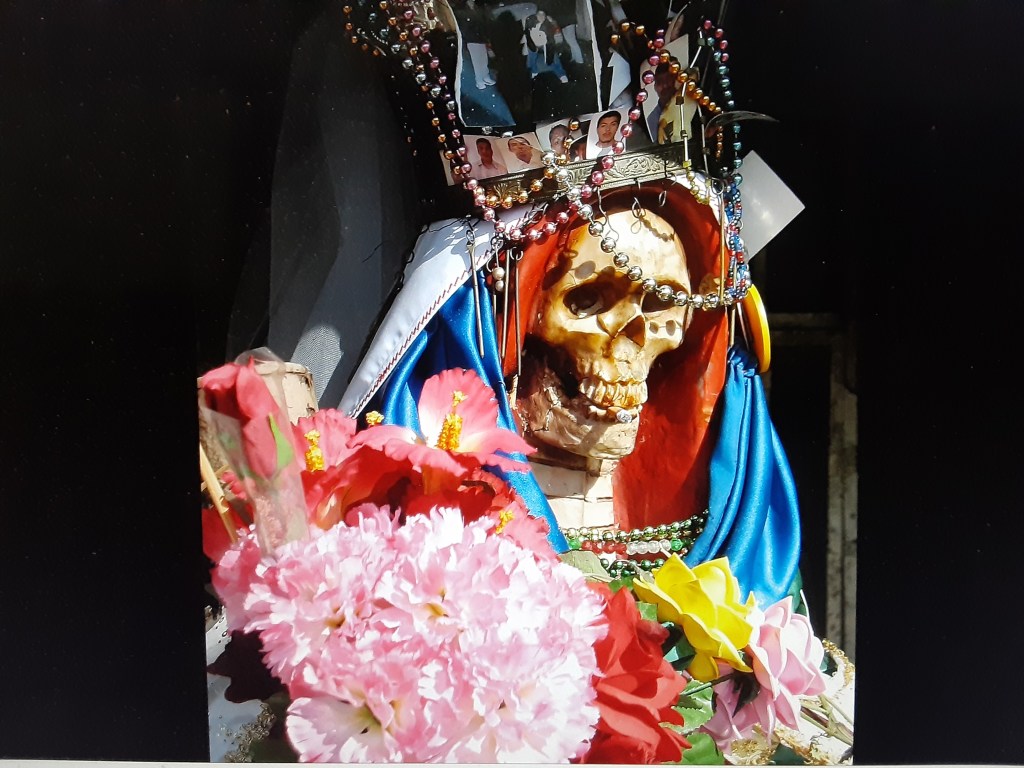

La Santa Muerte and Malverde are everywhere in San Cristóbal de las Casas and in Chiapas cities like Teopisca. Their cult is not hidden. The markets are replete with ritual elements appropriate for their veneration. The herbal and magic shops of ancient Jovel [1] now have monumental Huesudas (Bony) and Malverde welcoming the faithful.

On April 17, Jerónimo Ruiz, leader of the Association of Tenants of Traditional Markets of Chiapas (Almetrach), was shot dead by two men on a motorcycle. Amid the chaos and panic, violence erupted in the northern part of the former Coleta capital. Two armed groups blocked streets, clashed, and set tires and houses on fire. Among other lucrative activities, Almetrach charges the artisans floor rights (protection fees).

Jerónimo was from a community near Betania/Teopisca ironically called Flores Magón. At the altar to the Niña Blanca that the deceased had in his house, there was an oath to avenge her death.

Two days after his crime, a recording warned: “San Cristobal and its surroundings, as you already realized, we have already entered and the cleanup has already begun, we are the Jalisco cartel and what happened to Jerónimo Ruiz is going to happen to Narciso Ruiz, alias El Narso, Calafas, Águila, Birria, Max and all those groups of “Scooters” (Motonetos) that are supporting these scourges.”

Chiapas is where the most diverse denominations flourish. Traditional churches coexist with expressions of popular religiosity. The veneration of the Santísima Muerte (Most Holy Death) has grown exponentially hand in hand with the growth of organized crime but also with other causes completely unrelated to it, such as healing by faith. Not all its faithful are engaged in illicit activities, but often, in a kind of syncretism, many of those who dedicate themselves to them find in the fervor of this religiosity the route to approach the sacred.

Teopisca, 30 kilometers from San Cristobal, is key on the route of undocumented migrants and drugs. In June 2022, gunmen shot and killed the mayor, Rubén de Jesús Valdez Díaz, of the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM), as he left his home. The hitmen were allegedly hired from Jovel’s “Scooters.”

The murder is part of the conflict over the municipality between two groups. Those of Betania, whose visible head is Javier Velázquez Díaz, alias La Pulga (now arrested), and those of the local group of former municipal president Luis Alberto Valdez Díaz, accused of robbing the municipality when he was mayor and brother of the murdered mayor. Local rumors point to him as the alleged mastermind of a fratricide.

Both gangs are linked to migrant smuggling (polleros) and the production and distribution of drugs. Those from Betania have laboratories in their deeply evangelical community.

The cult of Huesudas and Malverde proliferates in the village. Large processions are held and there is more and more devotion to them. As part of the norteñización [2] of popular culture, narcocorridos proliferate. The groups “levantan” (lift up, or kidnap) the humblest young people. They walk around the town with impunity with high-caliber weapons and bulletproof vests. It is common to hear bursts shot into the air.

One of the factions wants to establish the municipal council of Teopisca. However, beyond the supposedly democratic demands, its promoters are also narcopolleros, who seek to convince communities by financing religious festivals. At the same time, they promise to build roads to the lowlands of the municipality, the central depression of Chiapas adjacent to the municipality of Venustiano Carranza, a key route to move drugs and undocumented immigrants.

According to inhabitants of the municipality, the group of former municipal president Luis Valdez would be linked to the Sinaloa [Cartel], while those of Betania de La Pulga would be part of the four letters (CJNG). They say that those from the Pacific [Sinaloa], who have more time in the region, do their business and do not mess with people, but those from Jalisco extort, kidnap, charge fees for protection, and so on. From their point of view, those from Sinaloa play at convenience, depending on the businesses in question and are calm, if you do not mess with them. But the New Generation are bad people.

What happens in San Cristobal and Teopisca is just a sample of what is happening throughout Chiapas. It is not an exception, but the rule. It’s part of a much larger plot. It is unimaginable to assume that the activities of these narco-polleros are unrelated to the networks of regional power and those responsible for maintaining order.

The Zapatista communities do not allow the planting, production and transfer of drugs. Their routes are closed to human traffickers. They do not take sides in disputes between cartels for control of markets and territories. They are a brake on the expansion of the criminal industry and on the business of authorities linked to them. Beyond their experience of self-government and self-management, among many reasons, that is why they have declared war on them. Also, because of this, old and new paramilitaries (some converted into narco-paramilitaries) have embarked on trying to destroy the autonomous communities.

The ORCAO attack on the [Zapatista support] bases of the Moisés Gandhi autonomous community, Lucio Cabañas rebel municipality, is part of a counterinsurgency strategy. Like Teopisca, it is not an abnormality but a constant in Chiapas politics. It is enough to look historically at the map of violence in the state to verify this.

The cults of Santa Muerte and Malverde have caught-on in the dry grass of southeastern Mexico. Their proliferation is a thermometer of what is happening socially.

[1] Jovel is the name of the valley in which San Cristóbal de las Casas is located.

[2] Norteñización refers to the popularization of Norteño music.

Originally Published in Spanish by La Jornada, Tuesday, June 13, 2023, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2023/06/13/opinion/019a1pol/ and Re-Published with English interpretation by the Chiapas Support Committee